Amanda Petrusich at The New Yorker:

Last August, Phish hosted a four-day music festival at a racetrack in Dover, Delaware. It was called Mondegreen—the word for a misheard lyric or phrase—and it was the band’s first festival since 2015. Phish—the singer and guitarist Trey Anastasio, the keyboardist Page McConnell, the bassist Mike Gordon, and the drummer Jon Fishman—was scheduled to play at least two sets a night for four nights in a row. No other bands were on the bill.

Last August, Phish hosted a four-day music festival at a racetrack in Dover, Delaware. It was called Mondegreen—the word for a misheard lyric or phrase—and it was the band’s first festival since 2015. Phish—the singer and guitarist Trey Anastasio, the keyboardist Page McConnell, the bassist Mike Gordon, and the drummer Jon Fishman—was scheduled to play at least two sets a night for four nights in a row. No other bands were on the bill.

Mondegreen kicked off on a Thursday. That afternoon, I joined a long line of cars inching through cornfields that surrounded the motorway. The horizon was wavy with exhaust. The sun was fluorescent. I gazed at the stalks, fantasizing about a “Field of Dreams”-type scenario in which a ballplayer would emerge from the corn and offer me a sweating bottle of water. Eventually, I texted a friend who was already at the campground. He expressed his sympathies, then volunteered to deliver edible marijuana to my car. I demurred, but it nonetheless felt like an appropriate welcome. I would soon come to understand these two impulses—fellowship and oblivion—as central to the Phish experience.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Steve Bannon, Trump’s first term whisperer, once described himself as a

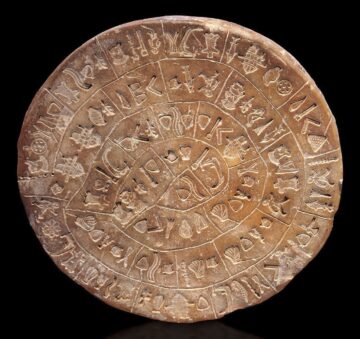

Steve Bannon, Trump’s first term whisperer, once described himself as a  I am a glyph-breaker. I confess. Guilty as charged. A glyph-breaker who didn’t break anything, and that is quite paradoxical, because, to be a true glyph-breaker, you should have deciphered an undeciphered script, like Jean-François Champollion (the founder of Egyptology, who decoded the Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs), Henry Rawlinson (who gave us the key to cuneiform) or Michael Ventris (who deciphered

I am a glyph-breaker. I confess. Guilty as charged. A glyph-breaker who didn’t break anything, and that is quite paradoxical, because, to be a true glyph-breaker, you should have deciphered an undeciphered script, like Jean-François Champollion (the founder of Egyptology, who decoded the Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs), Henry Rawlinson (who gave us the key to cuneiform) or Michael Ventris (who deciphered  As with so many other scientific controversies in our political life, public opinion on Covid origins has come to track — and serve as a signifier for — partisan identity. This bodes ill for dispassionate investigation, which we must have if we want to know the truth about what actually threw the world into chaos for years and

As with so many other scientific controversies in our political life, public opinion on Covid origins has come to track — and serve as a signifier for — partisan identity. This bodes ill for dispassionate investigation, which we must have if we want to know the truth about what actually threw the world into chaos for years and  “The University will not surrender its independence or relinquish its constitutional rights,”

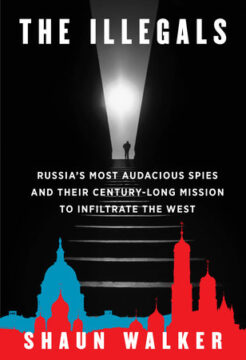

“The University will not surrender its independence or relinquish its constitutional rights,”  The fundamental role of intelligence agencies is to obtain information about other countries not available through open channels. Much of this work is done in the shadows, and most intelligence agencies use undercover operatives. The simplest way to do so is to disguise spies as diplomats. If caught, they can simply return home, claiming diplomatic immunity. But this also makes it easy for a host nation’s counterintelligence services to monitor the operatives. Diplomats are known entities and are tracked carefully. Some intelligence agencies will therefore use a riskier but harder-to-detect option. A spy is dispatched abroad posing as a business executive or other innocent-seeming professional, perhaps carving out a long and successful career in the cover role while all the time secretly developing useful sources and sending back intelligence. The CIA calls this “non-official cover.”

The fundamental role of intelligence agencies is to obtain information about other countries not available through open channels. Much of this work is done in the shadows, and most intelligence agencies use undercover operatives. The simplest way to do so is to disguise spies as diplomats. If caught, they can simply return home, claiming diplomatic immunity. But this also makes it easy for a host nation’s counterintelligence services to monitor the operatives. Diplomats are known entities and are tracked carefully. Some intelligence agencies will therefore use a riskier but harder-to-detect option. A spy is dispatched abroad posing as a business executive or other innocent-seeming professional, perhaps carving out a long and successful career in the cover role while all the time secretly developing useful sources and sending back intelligence. The CIA calls this “non-official cover.” Precisely for this strong physical, cultural, symbolic, and economic relationship with the Palestinians, olive trees have become targets for violence by the state of Israel and by Israeli settlers. A study published in 2012 by the Applied Research Institute Jerusalem estimated that since 1967 Israeli authorities have uprooted eight hundred thousand Palestinian olive trees in the West

Precisely for this strong physical, cultural, symbolic, and economic relationship with the Palestinians, olive trees have become targets for violence by the state of Israel and by Israeli settlers. A study published in 2012 by the Applied Research Institute Jerusalem estimated that since 1967 Israeli authorities have uprooted eight hundred thousand Palestinian olive trees in the West  Throughout the past month, several groups of Harvard alumni and faculty members have written and signed open letters encouraging President Alan M. Garber and the Corporation to stand up to the Trump administration. The ways in which the letters build off each other, adjusting requests over time, reflect the changing nature of the government’s pressures on higher education.

Throughout the past month, several groups of Harvard alumni and faculty members have written and signed open letters encouraging President Alan M. Garber and the Corporation to stand up to the Trump administration. The ways in which the letters build off each other, adjusting requests over time, reflect the changing nature of the government’s pressures on higher education. A distant planet’s atmosphere shows signs of molecules that on Earth are associated only with biological activity, a possible signal of life on what is suspected to be a watery world, according to a report published Wednesday that analyzed observations by NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope.

A distant planet’s atmosphere shows signs of molecules that on Earth are associated only with biological activity, a possible signal of life on what is suspected to be a watery world, according to a report published Wednesday that analyzed observations by NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope. As the global response to tariffs and concerns about inflation reach a fever pitch, Brown University political economist Mark Blyth is rethinking conventional economic wisdom on why prices go up and how policymakers can wrestle them back down.

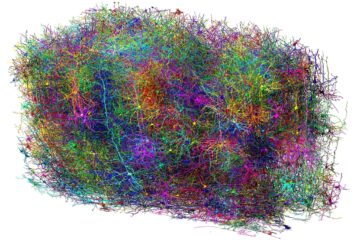

As the global response to tariffs and concerns about inflation reach a fever pitch, Brown University political economist Mark Blyth is rethinking conventional economic wisdom on why prices go up and how policymakers can wrestle them back down. The human brain is so complex that scientific brains have a hard time making sense of it. A piece of neural tissue the size of a grain of sand might be packed with hundreds of thousands of cells linked together by miles of wiring. In 1979, Francis Crick, the Nobel-prize-winning scientist, concluded that the anatomy and activity in just a cubic millimeter of brain matter would forever exceed our understanding.

The human brain is so complex that scientific brains have a hard time making sense of it. A piece of neural tissue the size of a grain of sand might be packed with hundreds of thousands of cells linked together by miles of wiring. In 1979, Francis Crick, the Nobel-prize-winning scientist, concluded that the anatomy and activity in just a cubic millimeter of brain matter would forever exceed our understanding.

It’s a bit of a long story. In brief, I had always wanted to make a porn film. I thought it was a genre that had never been treated with much artfulness or experimentation. I mentioned this interest of mine online, and someone in the porn industry contacted me to say he could get a porn film by me financed and made. I asked him if there were any restrictions or rules, and he said I could write any kind of script I wanted. So I wrote a quite complicated, strange porn script, very explicit but more about eroticism and how that works than actually being erotic. The script turned out to be way too experimental to get financed. So that project died. Years later, a German film producer, Jurgen Bruening, heard about the script, asked to read it, and said he might be interested in producing it. I was collaborating with Zac Farley on other projects by then. I asked if he was interested in working with me, and he agreed. We rewrote the script, taking out most of the actual hardcore porn, and submitted it. Jurgen Bruening liked the script and produced the film for very ittle money, $40,000. So we made Like Cattle Towards Glow. Neither Zac nor I had ever made a film before, but we saw it as a kind of strange, shot-in-the-dark experiment to see what would happen, and it worked out strangely well.

It’s a bit of a long story. In brief, I had always wanted to make a porn film. I thought it was a genre that had never been treated with much artfulness or experimentation. I mentioned this interest of mine online, and someone in the porn industry contacted me to say he could get a porn film by me financed and made. I asked him if there were any restrictions or rules, and he said I could write any kind of script I wanted. So I wrote a quite complicated, strange porn script, very explicit but more about eroticism and how that works than actually being erotic. The script turned out to be way too experimental to get financed. So that project died. Years later, a German film producer, Jurgen Bruening, heard about the script, asked to read it, and said he might be interested in producing it. I was collaborating with Zac Farley on other projects by then. I asked if he was interested in working with me, and he agreed. We rewrote the script, taking out most of the actual hardcore porn, and submitted it. Jurgen Bruening liked the script and produced the film for very ittle money, $40,000. So we made Like Cattle Towards Glow. Neither Zac nor I had ever made a film before, but we saw it as a kind of strange, shot-in-the-dark experiment to see what would happen, and it worked out strangely well. A lot of what comes in William Blake and the Sea Monsters of Love is about fellow enthusiasts rather than about Blake himself. It opens with Derek Jarman at the Avebury stone circle, treading in the footsteps of Paul Nash; then, by what Coleridge called the ‘streamy nature of association’, we follow Nash on his first trip to London in 1906, where, at the Carfax gallery, he saw an exhibition of Blake’s pictures. These moved him greatly – or, as Hoare puts it, ‘A crack in the sky opened up and a hand reached down.’ Another cut then takes us to John Singer Sargent in 1894 painting his memorable portrait of W Graham Robertson, who later illustrated a book called Pan’s Garden by his friend Algernon Blackwood, who purchased a great collection of Blake’s pictures from the family of his devoted patron Thomas Butts. Those were the paintings displayed in the Carfax gallery. As Nash looked at them, says Hoare, he saw ‘the god behind the machine’ – the machine in question being the modern industrial world of ‘science and rationalism’, that familiar bogey whom we can all deplore while enjoying its many benefits.

A lot of what comes in William Blake and the Sea Monsters of Love is about fellow enthusiasts rather than about Blake himself. It opens with Derek Jarman at the Avebury stone circle, treading in the footsteps of Paul Nash; then, by what Coleridge called the ‘streamy nature of association’, we follow Nash on his first trip to London in 1906, where, at the Carfax gallery, he saw an exhibition of Blake’s pictures. These moved him greatly – or, as Hoare puts it, ‘A crack in the sky opened up and a hand reached down.’ Another cut then takes us to John Singer Sargent in 1894 painting his memorable portrait of W Graham Robertson, who later illustrated a book called Pan’s Garden by his friend Algernon Blackwood, who purchased a great collection of Blake’s pictures from the family of his devoted patron Thomas Butts. Those were the paintings displayed in the Carfax gallery. As Nash looked at them, says Hoare, he saw ‘the god behind the machine’ – the machine in question being the modern industrial world of ‘science and rationalism’, that familiar bogey whom we can all deplore while enjoying its many benefits.