Sarah Miller at n+1:

On the second night the ayahuasca tasted terrible, like the entire jungle had shit into my mouth. The first sign of intoxication came in the form of a ticking sound. Next, I felt that there was a seam being stitched into my face. The seam was not painful, but something was tugging at it, the same entity that was making the ticking noise, and as the ticking noise increased, the tension also increased. When I imagined my face, in my mind’s eye, it was blank, no features, not even skin, covered with thick stocking fabric. I searched in vain for the part of my brain that could remind me this was not real. What was my name? What was the name of this scary drug I was on?

On the second night the ayahuasca tasted terrible, like the entire jungle had shit into my mouth. The first sign of intoxication came in the form of a ticking sound. Next, I felt that there was a seam being stitched into my face. The seam was not painful, but something was tugging at it, the same entity that was making the ticking noise, and as the ticking noise increased, the tension also increased. When I imagined my face, in my mind’s eye, it was blank, no features, not even skin, covered with thick stocking fabric. I searched in vain for the part of my brain that could remind me this was not real. What was my name? What was the name of this scary drug I was on?

The ticking sound turned into the sound of rustling feathers. I sat up, trying not to give in to the Medicine, but then I had to lie down. The rustling went on and on, for hours, and I saw nothing but dirty feathers, broken plates and cutlery and swatches of fabric, refrigerator interiors and bathroom tiles and grandmothers’ wheelchairs and enema bags and pill containers and tomato egg timers and Pet Rocks from homes I’d been to in elementary school.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Faced with unrelenting Russian aggression and the simultaneous withdrawal of American military and diplomatic support, European countries across the continent are reinvesting in defence. But civilian protection – non-military measures for civil defence, including the construction of nuclear and air raid bunkers – has also emerged as a fresh priority. In January, Norway reintroduced a cold war-era

Faced with unrelenting Russian aggression and the simultaneous withdrawal of American military and diplomatic support, European countries across the continent are reinvesting in defence. But civilian protection – non-military measures for civil defence, including the construction of nuclear and air raid bunkers – has also emerged as a fresh priority. In January, Norway reintroduced a cold war-era During the First World War, a six-year-old Simone Weil learned that soldiers on the Western Front were not rationed sugar, so she refused to eat it until conditions improved. But whereas most leave such zealous empathy in childhood, Weil’s commitment to suffering with — or, at least, in the same way as — others became the hallmark of her work as a philosopher and political activist, as well as of her short, harrowing life. And though her ascetic self-denial tended toward self-erasure, a theme she would reflect endlessly upon in her writing, she couldn’t help standing out. At the École Normale Supérieure, the elite Paris institution of higher learning where she was among the first generation of women to be educated, she was known as “The Red Virgin,” a testament to her asceticism, her communism, and, as her peers saw it, her scorn for femininity. (An improvement, perhaps, on “The Martian,” the sobriquet given to her by her lycée teacher, the radical pacifist philosopher, Alain.)

During the First World War, a six-year-old Simone Weil learned that soldiers on the Western Front were not rationed sugar, so she refused to eat it until conditions improved. But whereas most leave such zealous empathy in childhood, Weil’s commitment to suffering with — or, at least, in the same way as — others became the hallmark of her work as a philosopher and political activist, as well as of her short, harrowing life. And though her ascetic self-denial tended toward self-erasure, a theme she would reflect endlessly upon in her writing, she couldn’t help standing out. At the École Normale Supérieure, the elite Paris institution of higher learning where she was among the first generation of women to be educated, she was known as “The Red Virgin,” a testament to her asceticism, her communism, and, as her peers saw it, her scorn for femininity. (An improvement, perhaps, on “The Martian,” the sobriquet given to her by her lycée teacher, the radical pacifist philosopher, Alain.) By using electrical microphones, amplifiers and electromechanical recorders, record companies could capture a far wider range of sound frequencies, with much higher fidelity. For the first time, recorded sound closely resembled what a live listener would hear. Over the ensuing years,

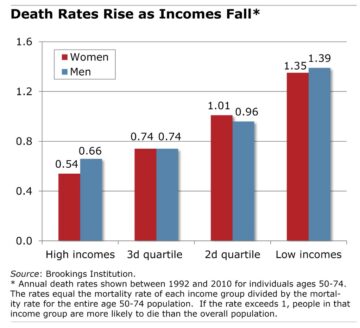

By using electrical microphones, amplifiers and electromechanical recorders, record companies could capture a far wider range of sound frequencies, with much higher fidelity. For the first time, recorded sound closely resembled what a live listener would hear. Over the ensuing years,  We examine the causal effect of health insurance on mortality using the universe of low-income adults, a dataset of 37 million individuals identified by linking the 2010 Census to administrative tax data. Our methodology leverages state-level variation in the timing and adoption of Medicaid expansions under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and earlier waivers and adheres to a preregistered analysis plan, a rarely used approach in observational studies in economics. We find that expansions increased Medicaid enrollment by 12 percentage points and reduced the mortality of the low-income adult population by 2.5 percent, suggesting a 21 percent reduction in the mortality hazard of new enrollees. Mortality reductions accrued not only to older age cohorts, but also to younger adults, who accounted for nearly half of life-years saved due to their longer remaining lifespans and large share of the low-income adult population. These expansions appear to be cost-effective, with direct budgetary costs of $5.4 million per life saved and $179,000 per life-year saved falling well below valuations commonly found in the literature. Our findings suggest that lack of health insurance explains about five to twenty percent of the mortality disparity between high- and low-income Americans. We contribute to a growing body of evidence that health insurance improves health and demonstrate that Medicaid’s life-saving effects extend across a broader swath of the low-income population than previously understood.

We examine the causal effect of health insurance on mortality using the universe of low-income adults, a dataset of 37 million individuals identified by linking the 2010 Census to administrative tax data. Our methodology leverages state-level variation in the timing and adoption of Medicaid expansions under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and earlier waivers and adheres to a preregistered analysis plan, a rarely used approach in observational studies in economics. We find that expansions increased Medicaid enrollment by 12 percentage points and reduced the mortality of the low-income adult population by 2.5 percent, suggesting a 21 percent reduction in the mortality hazard of new enrollees. Mortality reductions accrued not only to older age cohorts, but also to younger adults, who accounted for nearly half of life-years saved due to their longer remaining lifespans and large share of the low-income adult population. These expansions appear to be cost-effective, with direct budgetary costs of $5.4 million per life saved and $179,000 per life-year saved falling well below valuations commonly found in the literature. Our findings suggest that lack of health insurance explains about five to twenty percent of the mortality disparity between high- and low-income Americans. We contribute to a growing body of evidence that health insurance improves health and demonstrate that Medicaid’s life-saving effects extend across a broader swath of the low-income population than previously understood.

T

T This is a pivotal

This is a pivotal  Weighing in at a single ounce, the white-crowned sparrow can fly 2,600 miles, from Mexico to Alaska, on its annual spring migration, sometimes traveling 300 miles in a single night. Arctic terns make even longer journeys of 10,000 miles and more from the Arctic Circle to Antarctica, while great snipes fly over food-poor deserts and seas, sometimes covering 4,200 miles in four days without stopping.

Weighing in at a single ounce, the white-crowned sparrow can fly 2,600 miles, from Mexico to Alaska, on its annual spring migration, sometimes traveling 300 miles in a single night. Arctic terns make even longer journeys of 10,000 miles and more from the Arctic Circle to Antarctica, while great snipes fly over food-poor deserts and seas, sometimes covering 4,200 miles in four days without stopping. Seamus Heaney was born on April 13,1939 (12 days after me) and 3 months after the death of Yeats. The Letters* begin in 1965, his miraculous year. His first book, Death of a Naturalist, was accepted by Faber & Faber; he got a teaching job at his alma mater, Queen’s University in Belfast; and he married Marie Devlin, whom he was pleased to call Madame and Herself.

Seamus Heaney was born on April 13,1939 (12 days after me) and 3 months after the death of Yeats. The Letters* begin in 1965, his miraculous year. His first book, Death of a Naturalist, was accepted by Faber & Faber; he got a teaching job at his alma mater, Queen’s University in Belfast; and he married Marie Devlin, whom he was pleased to call Madame and Herself. “Reduce, reuse, recycle”: these three words have become as ubiquitous as the plastic waste they attempt to combat. Once seen as a simple roadmap toward sustainability, this mantra now conceals a far more complex and troubling reality. While these principles serve as a starting point for environmental action, they also have a deceptive history rooted in the petrochemical industry’s effort to avoid accountability. The truth is, no matter how diligently we sort our waste products, individual actions alone cannot solve the growing crisis of plastic pollution.

“Reduce, reuse, recycle”: these three words have become as ubiquitous as the plastic waste they attempt to combat. Once seen as a simple roadmap toward sustainability, this mantra now conceals a far more complex and troubling reality. While these principles serve as a starting point for environmental action, they also have a deceptive history rooted in the petrochemical industry’s effort to avoid accountability. The truth is, no matter how diligently we sort our waste products, individual actions alone cannot solve the growing crisis of plastic pollution.