Adam Tooze at Chartbook:

In 1944 after the liberation of Majdanek, where the soviet troops discovered warehouses of shoes and human hair, the term “death factory” gained general currency. Through wartime propaganda channels the Soviet pamphlet, Majdanek the death factory near Lublin by Konstantin Simonov acquired a circulation in the West. In the exhibitionary complex of the holocaust, the shoes from the Majdanek warehouse have become another icon, especially since a large collection of them were donated to the Holocaust memorial museum in Washington DC.

In 1944 after the liberation of Majdanek, where the soviet troops discovered warehouses of shoes and human hair, the term “death factory” gained general currency. Through wartime propaganda channels the Soviet pamphlet, Majdanek the death factory near Lublin by Konstantin Simonov acquired a circulation in the West. In the exhibitionary complex of the holocaust, the shoes from the Majdanek warehouse have become another icon, especially since a large collection of them were donated to the Holocaust memorial museum in Washington DC.

As the researcher Joachim Neander showed in his remarkable essay – “”Seife aus Judenfett” – Zur Wirkungsgeschichte einer Urban Legend” – the soap myth is itself an instance of the conceptualization of the Holocaust as industrialism. The idea that the Germans turned their victims into soap originated in fact in the generation before the Holocaust in a fearful rumor that began to circulate at the end of World War I. As the economic situation of Wilhelmine Germany became desperate and POW along with Germans began to starve, rumors began to circulate that the Kaiser’s regime was rendering the bodies of Belgian and other prisoners of war to make soap.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

One July afternoon in 2024,

One July afternoon in 2024,  Among the cognitive debilities that occur over time is rigidity in one’s fundamental outlook and assumptions about life. One’s outlook is usually set relatively early in life; usually by early adulthood you are either a liberal or a conservative; a nationalist or an internationalist; a risk-taker or someone habitually fearful and cautious. There is a lot of happy talk among gerontologists about how people can remain open to new ideas and able to reinvent their lives late in life, and that certainly happens with some individuals. But the truth of the matter is that fundamental change in mental outlooks becomes much less likely with age.

Among the cognitive debilities that occur over time is rigidity in one’s fundamental outlook and assumptions about life. One’s outlook is usually set relatively early in life; usually by early adulthood you are either a liberal or a conservative; a nationalist or an internationalist; a risk-taker or someone habitually fearful and cautious. There is a lot of happy talk among gerontologists about how people can remain open to new ideas and able to reinvent their lives late in life, and that certainly happens with some individuals. But the truth of the matter is that fundamental change in mental outlooks becomes much less likely with age. I

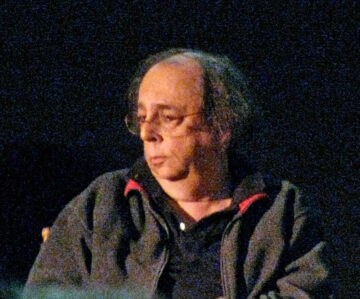

I  Google “Richard Foreman” and one of your first hits will invariably be the treasured playwright and director’s New York Times obit, which lists a cavalcade of prestigious awards as calculable proof of both his profound significance and old-school avant-garde don’t-give-’em-what-they-want bona fides. The first search page will inevitably include a link to Ontological.com, homepage of the Ontological-Hysteric Theater, the company Foreman established in 1968 to stage Angelface, his first produced play, at Jonas Mekas’s Film-Makers’ Cinematheque in New York. While the site could use updating, it contains info galore on the eighty shows that Foreman wrote and directed himself or staged by other authors; the films and videos he sporadically created; and the numerous books he published, including scripts, manifestos, essays, and one 1997 novel, No-body. The transcribed “notebooks” section of the site features more than fifty downloadable files of free-floating dialogue that he offered up for others to use in their own productions. Not enough? You should visit the Foreman page at the PennSound website, a virtual trove of performance documentation, interviews, readings, and even the sound loops from his 2001 show Now That Communism Is Dead My Life Feels Empty! Too much? You could simply skim Foreman’s bountiful Wikipedia page, given that I just corrected it. Someone had named the artist Kate Manheim—Foreman’s remarkable widow, who for many years was his star actress—as being his first wife. She was his second. The brilliant film critic Amy Taubin preceded her. Now you know!

Google “Richard Foreman” and one of your first hits will invariably be the treasured playwright and director’s New York Times obit, which lists a cavalcade of prestigious awards as calculable proof of both his profound significance and old-school avant-garde don’t-give-’em-what-they-want bona fides. The first search page will inevitably include a link to Ontological.com, homepage of the Ontological-Hysteric Theater, the company Foreman established in 1968 to stage Angelface, his first produced play, at Jonas Mekas’s Film-Makers’ Cinematheque in New York. While the site could use updating, it contains info galore on the eighty shows that Foreman wrote and directed himself or staged by other authors; the films and videos he sporadically created; and the numerous books he published, including scripts, manifestos, essays, and one 1997 novel, No-body. The transcribed “notebooks” section of the site features more than fifty downloadable files of free-floating dialogue that he offered up for others to use in their own productions. Not enough? You should visit the Foreman page at the PennSound website, a virtual trove of performance documentation, interviews, readings, and even the sound loops from his 2001 show Now That Communism Is Dead My Life Feels Empty! Too much? You could simply skim Foreman’s bountiful Wikipedia page, given that I just corrected it. Someone had named the artist Kate Manheim—Foreman’s remarkable widow, who for many years was his star actress—as being his first wife. She was his second. The brilliant film critic Amy Taubin preceded her. Now you know! “This whole process, it’s just inefficient,” says Saar Gill, a haematologist and oncologist also at the Perelman School of Medicine. “If I’ve got a patient with cancer, I can prescribe chemotherapy and they’ll get it tomorrow.” With commercial CAR T, however, people have to wait weeks for treatment. That delay, along with the high cost of the therapy, plus the need for chemotherapy before people receive the CAR T cells, means many people who could benefit from CAR T never receive it. “We all want to get to a situation where CAR T cells are more like a drug,” says Gill.

“This whole process, it’s just inefficient,” says Saar Gill, a haematologist and oncologist also at the Perelman School of Medicine. “If I’ve got a patient with cancer, I can prescribe chemotherapy and they’ll get it tomorrow.” With commercial CAR T, however, people have to wait weeks for treatment. That delay, along with the high cost of the therapy, plus the need for chemotherapy before people receive the CAR T cells, means many people who could benefit from CAR T never receive it. “We all want to get to a situation where CAR T cells are more like a drug,” says Gill. When Edward Said’s book,

When Edward Said’s book,  Richard Garwin, who died on May 13, 2025, at the age of 97, was sometimes called “

Richard Garwin, who died on May 13, 2025, at the age of 97, was sometimes called “ Israel’s former Prime Minister Ehud Olmert says he now believes his country’s relentless assault on the Palestinian people amounts to “war crimes” and must be stopped.

Israel’s former Prime Minister Ehud Olmert says he now believes his country’s relentless assault on the Palestinian people amounts to “war crimes” and must be stopped. In November, when the “Succession” creator Jesse Armstrong got the idea for his caustic new movie, “Mountainhead,” he knew he wanted to do it fast. He wrote the script, about grandiose, nihilistic tech oligarchs holed up in a mountain mansion in Utah, in January and February, as a very similar set of oligarchs was coalescing behind Donald Trump’s inauguration. Then he shot the film, his first, over five weeks this spring. It premiers on Saturday on HBO — an astonishingly compressed timeline. With events cascading so quickly that last year often feels like another era, Armstrong wanted to create what he called, when I spoke to him last week, “a feeling of nowness.”

In November, when the “Succession” creator Jesse Armstrong got the idea for his caustic new movie, “Mountainhead,” he knew he wanted to do it fast. He wrote the script, about grandiose, nihilistic tech oligarchs holed up in a mountain mansion in Utah, in January and February, as a very similar set of oligarchs was coalescing behind Donald Trump’s inauguration. Then he shot the film, his first, over five weeks this spring. It premiers on Saturday on HBO — an astonishingly compressed timeline. With events cascading so quickly that last year often feels like another era, Armstrong wanted to create what he called, when I spoke to him last week, “a feeling of nowness.” The artist

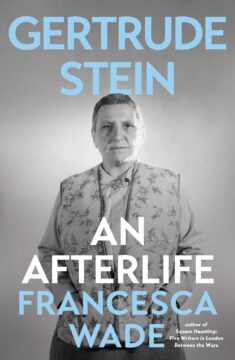

The artist  It’s not often that a biography really gets going after the author has reached the subject’s death. Gertrude Stein herself predicted that she would only be understood in the future: ‘For a very long time everybody refuses and then almost without a pause almost everybody accepts.’ She wasn’t entirely right, but Francesca Wade’s new ‘afterlife’ of Stein takes the sentiment seriously. The revolutions in language that preoccupied Stein in life were slowly appreciated after her death in 1946. Despite having an unpromising cast of scholars, librarians, publishers and fans, Wade turns the posthumous half of the Stein story into a narrative of suppression, revelation and hopes fulfilled. It helps that there is romance at the heart of it, and a secret notebook.

It’s not often that a biography really gets going after the author has reached the subject’s death. Gertrude Stein herself predicted that she would only be understood in the future: ‘For a very long time everybody refuses and then almost without a pause almost everybody accepts.’ She wasn’t entirely right, but Francesca Wade’s new ‘afterlife’ of Stein takes the sentiment seriously. The revolutions in language that preoccupied Stein in life were slowly appreciated after her death in 1946. Despite having an unpromising cast of scholars, librarians, publishers and fans, Wade turns the posthumous half of the Stein story into a narrative of suppression, revelation and hopes fulfilled. It helps that there is romance at the heart of it, and a secret notebook.