Victoria Malloy in Atmos:

The concept of bringing back the scent of extinct flowers started with Ginkgo Bioworks, a Boston-based biotech company founded by five MIT scientists, with an ethos rooted in the lessons of Jurassic Park: that life finds a way. “A lot of the story of biotechnology for the past two decades has been talking about living things through the metaphor of computers and code,” said Christina Agapakis, an interdisciplinary synthetic biologist and former head of creative at Ginkgo Bioworks. “Living things are coded with DNA. Now, life can be programmable.”

The concept of bringing back the scent of extinct flowers started with Ginkgo Bioworks, a Boston-based biotech company founded by five MIT scientists, with an ethos rooted in the lessons of Jurassic Park: that life finds a way. “A lot of the story of biotechnology for the past two decades has been talking about living things through the metaphor of computers and code,” said Christina Agapakis, an interdisciplinary synthetic biologist and former head of creative at Ginkgo Bioworks. “Living things are coded with DNA. Now, life can be programmable.”

At the Harvard University Herbarium, more than 5 million specimens of algae, fungi, and plants are preserved—pressed, labeled, and stored in floor-to-ceiling cabinets that stretch back centuries. Researchers have long used these collections to study biodiversity and evolutionary history. But in a video providing a look inside the Harvard Herbarium, Charles Davis, a professor of organismic and evolutionary biology and curator of vascular plants, underscored that natural history collections are today seeing a renewed purpose for advancing innovation in the face of accelerating climate change and a sixth mass extinction.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Several recent books chronicling specifically American Jewish dissent from Zionism, past and present, demonstrate how this relatively recent Zionist “consensus” was manufactured. Geoffrey Levin and Marjorie N. Feld tell stories of once-mainstream dissidents and naysayers purged from the ranks of even straightforwardly liberal American Jewish institutions, demonstrating the force with which unconditional support for Israel had to be constructed from the top down in the immediate postwar era. Looking to the more recent past, Oren Kroll-Zeldin and Peter Beinart examine efforts—in Beinart’s case, his own—to break through that heavily policed consensus since the turn of the century.

Several recent books chronicling specifically American Jewish dissent from Zionism, past and present, demonstrate how this relatively recent Zionist “consensus” was manufactured. Geoffrey Levin and Marjorie N. Feld tell stories of once-mainstream dissidents and naysayers purged from the ranks of even straightforwardly liberal American Jewish institutions, demonstrating the force with which unconditional support for Israel had to be constructed from the top down in the immediate postwar era. Looking to the more recent past, Oren Kroll-Zeldin and Peter Beinart examine efforts—in Beinart’s case, his own—to break through that heavily policed consensus since the turn of the century. Unlike the other usual contenders for the title of greatest living American composer, who rose up out of lofts and art galleries (Glass, Reich) or Hollywood recording studios (John Williams), Adams is a denizen of the concert hall and the opera house—the restless maximalism of his greatest works is at its best live, heard with undivided attention. And unlike the atonal modernism he rejected, his music has a certain populist quality, a fundamental legibility to broad audiences. But keeping track of the rapidly shifting moods and subversions and extensions of musical convention may be an acquired taste: It can seem that the innovations that made his reputation have simultaneously restricted his renown largely to the confines that the classical music world has created for itself.

Unlike the other usual contenders for the title of greatest living American composer, who rose up out of lofts and art galleries (Glass, Reich) or Hollywood recording studios (John Williams), Adams is a denizen of the concert hall and the opera house—the restless maximalism of his greatest works is at its best live, heard with undivided attention. And unlike the atonal modernism he rejected, his music has a certain populist quality, a fundamental legibility to broad audiences. But keeping track of the rapidly shifting moods and subversions and extensions of musical convention may be an acquired taste: It can seem that the innovations that made his reputation have simultaneously restricted his renown largely to the confines that the classical music world has created for itself. What does it mean to be modern? The answer was largely determined rather early in the modern era by three thinkers who, as luck would have it, not only came from the same place and spoke the same language but were also near contemporaries. When René Descartes was born in 1596, Michel de Montaigne had only been dead for four years. Blaise Pascal, the third of them, was born in 1623, when Descartes was not even thirty and yet to make a name for himself. In 1647, Pascal and Descartes, the young scientific prodigy and the celebrated founder of modern rationalism, would meet in person, but the encounter didn’t go very well. Descartes didn’t seem particularly impressed by Pascal, while Pascal must have found Descartes a touch too patronising. To ensure the survival of their mutual admiration, certain people should perhaps steer clear of each other.

What does it mean to be modern? The answer was largely determined rather early in the modern era by three thinkers who, as luck would have it, not only came from the same place and spoke the same language but were also near contemporaries. When René Descartes was born in 1596, Michel de Montaigne had only been dead for four years. Blaise Pascal, the third of them, was born in 1623, when Descartes was not even thirty and yet to make a name for himself. In 1647, Pascal and Descartes, the young scientific prodigy and the celebrated founder of modern rationalism, would meet in person, but the encounter didn’t go very well. Descartes didn’t seem particularly impressed by Pascal, while Pascal must have found Descartes a touch too patronising. To ensure the survival of their mutual admiration, certain people should perhaps steer clear of each other. In 2025, in accordance with Moore’s Law, we’ll see an acceleration in the rate of change as we move closer to a world of true abundance. Here are eight areas where we’ll see extraordinary transformation in the next decade:

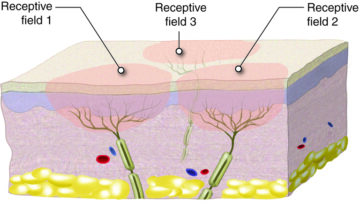

In 2025, in accordance with Moore’s Law, we’ll see an acceleration in the rate of change as we move closer to a world of true abundance. Here are eight areas where we’ll see extraordinary transformation in the next decade: Pain might flicker, flash, prickle, drill, lancinate, pinch, cramp, tug, scald, sear, or itch. It might be blinding, or gruelling, or annoying, and it might, additionally, radiate, squeeze, or tear with an intensity that is mild, distressing, or excruciating. Yet understanding someone else’s pain is like understanding another person’s dream. The dreamer searches out the right words to communicate it; the words are always insufficient and imprecise. In 1971, the psychologist Ronald Melzack developed a vocabulary for pain, to make communication less cloudy. His McGill Pain Questionnaire, versions of which are still in use today, comprises seventy-eight words, divided into twenty groups, with an additional five words to describe intensity and nine to describe pain’s relationship to time, from transient to intermittent to constant. Not included in the M.P.Q. is the language that Friedrich Nietzsche used in describing the migraines that afflicted him: “I have given a name to my pain and call it ‘dog.’ It is just as faithful, just as obtrusive and shameless, just as entertaining, just as clever as any other dog.”

Pain might flicker, flash, prickle, drill, lancinate, pinch, cramp, tug, scald, sear, or itch. It might be blinding, or gruelling, or annoying, and it might, additionally, radiate, squeeze, or tear with an intensity that is mild, distressing, or excruciating. Yet understanding someone else’s pain is like understanding another person’s dream. The dreamer searches out the right words to communicate it; the words are always insufficient and imprecise. In 1971, the psychologist Ronald Melzack developed a vocabulary for pain, to make communication less cloudy. His McGill Pain Questionnaire, versions of which are still in use today, comprises seventy-eight words, divided into twenty groups, with an additional five words to describe intensity and nine to describe pain’s relationship to time, from transient to intermittent to constant. Not included in the M.P.Q. is the language that Friedrich Nietzsche used in describing the migraines that afflicted him: “I have given a name to my pain and call it ‘dog.’ It is just as faithful, just as obtrusive and shameless, just as entertaining, just as clever as any other dog.” In the first movement of his piece, Messiaen wanted to create the strange sense of time ending. He achieved this in the most stunning manner. Time depends on things repeating, so he needed to produce a structure where you never truly hear the moment of repetition. While the clarinet imitates a blackbird and the violin a nightingale, the piano part plays a 17-note syncopated rhythm that just repeats itself over and over. But the chord sequence that the pianist plays, set to this rhythm sequence, consists of 29 chords, which are again repeated over and over. Such repeating patterns might lead to boredom and predictability, but not in this case. Because Messiaen’s choice of numbers—17 and 29—means that something rather magical… or mathematical, occurs. The numbers he chose are prime numbers, and their mutual indivisibility means that the rhythm and harmony that Messiaen has set up never get back in sync once the piece is in motion.

In the first movement of his piece, Messiaen wanted to create the strange sense of time ending. He achieved this in the most stunning manner. Time depends on things repeating, so he needed to produce a structure where you never truly hear the moment of repetition. While the clarinet imitates a blackbird and the violin a nightingale, the piano part plays a 17-note syncopated rhythm that just repeats itself over and over. But the chord sequence that the pianist plays, set to this rhythm sequence, consists of 29 chords, which are again repeated over and over. Such repeating patterns might lead to boredom and predictability, but not in this case. Because Messiaen’s choice of numbers—17 and 29—means that something rather magical… or mathematical, occurs. The numbers he chose are prime numbers, and their mutual indivisibility means that the rhythm and harmony that Messiaen has set up never get back in sync once the piece is in motion. The goal of understanding how inert molecules gave rise to life is one step closer, according to researchers who have created a system of RNA molecules that can partly replicate itself. They say it should one day

The goal of understanding how inert molecules gave rise to life is one step closer, according to researchers who have created a system of RNA molecules that can partly replicate itself. They say it should one day  Public gaffes piled up. Biden referred to Vice President Harris as “Vice President Trump” and described himself as the first black vice president. At a NATO summit President Zelensky of Ukraine was called “President Putin.” Behind the scenes at photo ops Biden would regularly fail to recognize long-time friends and colleagues. Even George Clooney, not a man used to being ignored, went unrecognized at a Hollywood fundraiser that he himself had organized. At campaign events Biden would repeat stories or simply allow them to peeter out into an embarrassed silence. He would lose his way coming off stage. His voice, hoarse at the best of times, would often become an inaudible whisper.

Public gaffes piled up. Biden referred to Vice President Harris as “Vice President Trump” and described himself as the first black vice president. At a NATO summit President Zelensky of Ukraine was called “President Putin.” Behind the scenes at photo ops Biden would regularly fail to recognize long-time friends and colleagues. Even George Clooney, not a man used to being ignored, went unrecognized at a Hollywood fundraiser that he himself had organized. At campaign events Biden would repeat stories or simply allow them to peeter out into an embarrassed silence. He would lose his way coming off stage. His voice, hoarse at the best of times, would often become an inaudible whisper. Why abstract art? The question is not rhetorical, especially as a point of entry into the visionary work of Jack Whitten, whose career spanned six decades before he died in 2018. One possible answer: the need to say what cannot be said according to the usual rules—rules for perspective, light, scale, and all the rest, but also, and maybe most importantly, rules for representing the world in a way that the world has already recognized. What looks real, what is real, may not be the same for you as it is for me. That makes it vitally important for artists to paint, sculpt, or draw the world as they see it, regardless of the rules. And that is particularly true when the rules—inside the world of art schools, galleries, and museums and, most especially, outside it—constitute the very evil that makes their work necessary.

Why abstract art? The question is not rhetorical, especially as a point of entry into the visionary work of Jack Whitten, whose career spanned six decades before he died in 2018. One possible answer: the need to say what cannot be said according to the usual rules—rules for perspective, light, scale, and all the rest, but also, and maybe most importantly, rules for representing the world in a way that the world has already recognized. What looks real, what is real, may not be the same for you as it is for me. That makes it vitally important for artists to paint, sculpt, or draw the world as they see it, regardless of the rules. And that is particularly true when the rules—inside the world of art schools, galleries, and museums and, most especially, outside it—constitute the very evil that makes their work necessary. In April 1649, the earth of

In April 1649, the earth of  Through a stroke of good fortune, Elon Musk’s otherwise disastrous purchase of Twitter has turned into one of the great business acquisitions of all time. Buying control of a president was a start. What if the deal bought him something even more valuable?

Through a stroke of good fortune, Elon Musk’s otherwise disastrous purchase of Twitter has turned into one of the great business acquisitions of all time. Buying control of a president was a start. What if the deal bought him something even more valuable? Autism spectrum disorder, or autism, is a neurodevelopmental disorder. People with the disorder may have deficits in social communication and interaction and restricted and repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities. Autism is really a construct, an idea that there is something different about people who have very basic deficits or difficulties in social communication, starting very young, and also certain repetitive or sensory differences compared to neurotypical people.

Autism spectrum disorder, or autism, is a neurodevelopmental disorder. People with the disorder may have deficits in social communication and interaction and restricted and repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities. Autism is really a construct, an idea that there is something different about people who have very basic deficits or difficulties in social communication, starting very young, and also certain repetitive or sensory differences compared to neurotypical people. The term “first-world problem” is used to describe the type of minor nuisance that occupies the minds of the bourgeoisie. You dropped an AirPod in the urinal. You spilled chardonnay on the divan. Whole Foods was out of pomegranates. And so forth. These are perfectly real frustrations, but they only afflict the comfortable. We might define a parallel quandary in the field of moral philosophy: the first-world ethical problem. These are dilemmas about right and wrong that don’t actually touch any of the major ethical crises of our time or issues of structural injustice. They’re problems that only arise or seem worthy of spending time on once you reach a certain level of wealth and privilege. The New York Times advice column,

The term “first-world problem” is used to describe the type of minor nuisance that occupies the minds of the bourgeoisie. You dropped an AirPod in the urinal. You spilled chardonnay on the divan. Whole Foods was out of pomegranates. And so forth. These are perfectly real frustrations, but they only afflict the comfortable. We might define a parallel quandary in the field of moral philosophy: the first-world ethical problem. These are dilemmas about right and wrong that don’t actually touch any of the major ethical crises of our time or issues of structural injustice. They’re problems that only arise or seem worthy of spending time on once you reach a certain level of wealth and privilege. The New York Times advice column,