From The Exiled Soul Library:

The Wall is a story of an unnamed woman in her 40s who finds herself cut off from the rest of the world by the sudden appearance of the wall made of unknow material that separates a part of the forest from the rest of the world. This occurrence takes place during the narrator’s visit to her cousin, Luise’s and her husband, Hugo’s lodge in the Austrian Alps. She was unable to find an explanation for the appearance of the wall and was not sure if only the valley or the whole country had been affected by this disaster. Thanks to Hugo the narrator had provisions that would keep her through some time, and a lifetime’s supply of wood. that allowed her to survive. She also had their dog, Lynx who became an integral part of her new life along with two cats and the cow. They became her new family. At the time when the wall appeared the narrator was widowed for two years, and her two daughters were almost grown up.

The Wall is a story of an unnamed woman in her 40s who finds herself cut off from the rest of the world by the sudden appearance of the wall made of unknow material that separates a part of the forest from the rest of the world. This occurrence takes place during the narrator’s visit to her cousin, Luise’s and her husband, Hugo’s lodge in the Austrian Alps. She was unable to find an explanation for the appearance of the wall and was not sure if only the valley or the whole country had been affected by this disaster. Thanks to Hugo the narrator had provisions that would keep her through some time, and a lifetime’s supply of wood. that allowed her to survive. She also had their dog, Lynx who became an integral part of her new life along with two cats and the cow. They became her new family. At the time when the wall appeared the narrator was widowed for two years, and her two daughters were almost grown up.

“I’d spent most of my life struggling with daily human concerns. (…) Since my childhood I had forgotten how to see things with my own eyes (…); loneliness led me, in moments free of memory and consciousness, to see the brilliance of life again. (…) I don’t know whether I will be able to bear living with reality alone. (…) I’m still a human being who thinks and feels. (…) That’s why I am sitting here writing down everything that’s happened (…). Writing is all that matters, and as there are no other conversations left, I have to keep the endless conversation with myself alive.”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

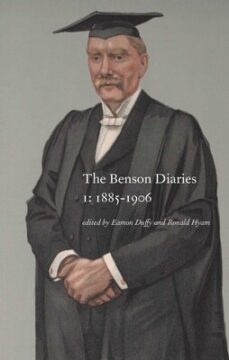

Benson was acerbic and often hilarious about other authors. He describes Henry James’s talk as boring but ‘intricate, magniloquent, rhetorical, humorous’, and quotes him as saying that ‘the difference between being with [J M] Barrie & not being with him was infinitesimal’. Asked whether any of the actresses introduced to him by Ellen Terry were pretty, James replied, ‘I must not go so far as to deny that one poor wanton had some species of cadaverous charm.’ Immensely fat, G K Chesterton got so hot at a Magdalene dinner that the sweat ran down his cigar and ‘hissed at the point’. Hilaire Belloc was scintillating but frowsy and tipsy, living in something like a ‘gypsy encampment’, which, Benson thought, should be burned to the ground. Accompanied by Edmund Gosse, Benson visited Thomas Hardy, whose features were ‘curiously worn & blurred & ruinous’; they might have belonged to ‘a retired half-pay officer, from a not very smart regiment’. Although admiring H G Wells, Benson deprecated his ‘strong cockney accent’ and his ‘glorification of animalism’.

Benson was acerbic and often hilarious about other authors. He describes Henry James’s talk as boring but ‘intricate, magniloquent, rhetorical, humorous’, and quotes him as saying that ‘the difference between being with [J M] Barrie & not being with him was infinitesimal’. Asked whether any of the actresses introduced to him by Ellen Terry were pretty, James replied, ‘I must not go so far as to deny that one poor wanton had some species of cadaverous charm.’ Immensely fat, G K Chesterton got so hot at a Magdalene dinner that the sweat ran down his cigar and ‘hissed at the point’. Hilaire Belloc was scintillating but frowsy and tipsy, living in something like a ‘gypsy encampment’, which, Benson thought, should be burned to the ground. Accompanied by Edmund Gosse, Benson visited Thomas Hardy, whose features were ‘curiously worn & blurred & ruinous’; they might have belonged to ‘a retired half-pay officer, from a not very smart regiment’. Although admiring H G Wells, Benson deprecated his ‘strong cockney accent’ and his ‘glorification of animalism’. C

C In 2023, one out of 20 Canadians who died received a physician-assisted death, making Canada the No. 1 provider of medical assistance in dying (MAID) in the world, when measured in total figures. In one province, Quebec, there were more MAID deaths per capita than anywhere else. Canadians, by and large, have been supportive of this trend. A 2022 poll showed that a stunning 86 percent of Canadians supported MAID’s legalization.

In 2023, one out of 20 Canadians who died received a physician-assisted death, making Canada the No. 1 provider of medical assistance in dying (MAID) in the world, when measured in total figures. In one province, Quebec, there were more MAID deaths per capita than anywhere else. Canadians, by and large, have been supportive of this trend. A 2022 poll showed that a stunning 86 percent of Canadians supported MAID’s legalization. From knowledge and expertise to planning, reasoning, creativity, and problem-solving, we could soon find ourselves

From knowledge and expertise to planning, reasoning, creativity, and problem-solving, we could soon find ourselves  In the early 2000s, political scientist Andreas Schedler coined the term “

In the early 2000s, political scientist Andreas Schedler coined the term “ Artificial intelligence

Artificial intelligence At midcentury, Marianne Moore emerged as a public personage, but not before a painful period of loss. Prefaced by a host of personal disasters—the death of her mother’s onetime partner Mary Norcross, her own hospitalization for digestive problems, her mother’s painful shingles and neuralgia—the decade of the 1940s brought sorrow. Moore had to deal with the rejection of her only attempt at a novel and the news that her Selected Poems had been remaindered at thirty cents a copy. Bouts of bursitis and bronchitis prompted her to hire a succession of nurses and helpers, one of whom—Gladys Berry—would work for Moore into her old age.

At midcentury, Marianne Moore emerged as a public personage, but not before a painful period of loss. Prefaced by a host of personal disasters—the death of her mother’s onetime partner Mary Norcross, her own hospitalization for digestive problems, her mother’s painful shingles and neuralgia—the decade of the 1940s brought sorrow. Moore had to deal with the rejection of her only attempt at a novel and the news that her Selected Poems had been remaindered at thirty cents a copy. Bouts of bursitis and bronchitis prompted her to hire a succession of nurses and helpers, one of whom—Gladys Berry—would work for Moore into her old age. WHEN MARCEL DUCHAMP mounted a challenge to Constantin Brancusi during a joint visit to an exhibition of new airplane technologies in Paris in 1912—asking Brancusi whether he could ever sculpt anything as perfect as an airplane propeller—he figured a contradiction that haunted sculptural production for the remaining part of the twentieth century and into the first two decades of the twenty-first: the dialectics between traditional artisanal and artistic modes of sculptural production and the ever more compelling paradigm of the technologically produced readymade. Obviously, this dialectic has been constitutive of Gabriel Orozco’s work from the very beginning and determines it to this very day.

WHEN MARCEL DUCHAMP mounted a challenge to Constantin Brancusi during a joint visit to an exhibition of new airplane technologies in Paris in 1912—asking Brancusi whether he could ever sculpt anything as perfect as an airplane propeller—he figured a contradiction that haunted sculptural production for the remaining part of the twentieth century and into the first two decades of the twenty-first: the dialectics between traditional artisanal and artistic modes of sculptural production and the ever more compelling paradigm of the technologically produced readymade. Obviously, this dialectic has been constitutive of Gabriel Orozco’s work from the very beginning and determines it to this very day. Dear Reader,

Dear Reader, In December 2013, not long after the publication of Mike Tyson’s autobiography, The Wall Street Journal asked him—along with forty‑nine other distinguished writers, academics, artists, politicians, and CEOs—to name their favorite books of the year. Among Tyson’s selections was a Kindle book,

In December 2013, not long after the publication of Mike Tyson’s autobiography, The Wall Street Journal asked him—along with forty‑nine other distinguished writers, academics, artists, politicians, and CEOs—to name their favorite books of the year. Among Tyson’s selections was a Kindle book,

T

T Two weeks ago, in the run-up to the release of her ninth studio album, “Something Beautiful,” Miley Cyrus, who is thirty-two and one of the most successful pop stars of all time, revealed, in an

Two weeks ago, in the run-up to the release of her ninth studio album, “Something Beautiful,” Miley Cyrus, who is thirty-two and one of the most successful pop stars of all time, revealed, in an