Jennifer Szalai at the NYT:

“America, América” is implicitly a companion volume to Grandin’s Pulitzer Prize-winning “The End of Myth,” which explored the role played by the frontier in the American imagination. Grandin posited that the mythology of an ever-expanding frontier encouraged fantasies of infinite growth and delusions of innocence. Instead of grappling with scarcity and contradiction, Americans learned simply to go west. He traced how the United States became “inured to its brutality and accustomed to a unique prerogative: its ability to organize politics around the promise of constant, endless expansion.”

“America, América” is implicitly a companion volume to Grandin’s Pulitzer Prize-winning “The End of Myth,” which explored the role played by the frontier in the American imagination. Grandin posited that the mythology of an ever-expanding frontier encouraged fantasies of infinite growth and delusions of innocence. Instead of grappling with scarcity and contradiction, Americans learned simply to go west. He traced how the United States became “inured to its brutality and accustomed to a unique prerogative: its ability to organize politics around the promise of constant, endless expansion.”

South of the United States, a starkly different experience made for a different understanding of the world. In “America, América,” Grandin shows how Spanish Americans viewed frontiers not as escape valves but “as historic theaters of terror and domination.” He maintains that this sense of anguish gave rise to a strain of Latin American humanism that became foundational to ideals of international cooperation and global institutions, including the United Nations.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

We hoped that our collective struggles had made a difference in ending a war that never should have been fought.

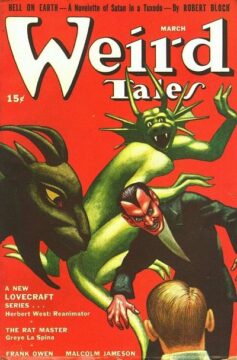

We hoped that our collective struggles had made a difference in ending a war that never should have been fought. A proposition: though “trash art” remains with us, the trash artist is a dying species. Trash art is focus-grouped these days, high-gloss. Trash art is a direct-to-streaming show full of people who are slightly too attractive that’s meant to be played in the background while you play Candy Crush on your phone. Even our truly lowbrow cultural productions, like The Bachelor, are not the product of particular people; they’re crafted through a system. Without romanticizing the old days of pulp magazines and Brill Building song writers, we can—ah hell! Let’s romanticize them. Why not? They certainly put out lots of garbage, but it was honest human garbage. Look at an old issue of Weird Tales—in terms of nostalgic reverence, the Partisan Review of pulp fiction—with its now charmingly dated pinup girls on the cover, and its promise of many stupid adventures within, and try not to romanticize it.

A proposition: though “trash art” remains with us, the trash artist is a dying species. Trash art is focus-grouped these days, high-gloss. Trash art is a direct-to-streaming show full of people who are slightly too attractive that’s meant to be played in the background while you play Candy Crush on your phone. Even our truly lowbrow cultural productions, like The Bachelor, are not the product of particular people; they’re crafted through a system. Without romanticizing the old days of pulp magazines and Brill Building song writers, we can—ah hell! Let’s romanticize them. Why not? They certainly put out lots of garbage, but it was honest human garbage. Look at an old issue of Weird Tales—in terms of nostalgic reverence, the Partisan Review of pulp fiction—with its now charmingly dated pinup girls on the cover, and its promise of many stupid adventures within, and try not to romanticize it. The Trump administration

The Trump administration  Last Wednesday night I received an email out of the blue from Larry David, the comedian and creator of “Curb Your Enthusiasm,” saying that he had a guest essay submission. I opened the document and read the first line: “Imagine my surprise when in the spring of 1939 a letter arrived at my house inviting me to dinner at the Old Chancellery with the world’s most reviled man, Adolf Hitler.”

Last Wednesday night I received an email out of the blue from Larry David, the comedian and creator of “Curb Your Enthusiasm,” saying that he had a guest essay submission. I opened the document and read the first line: “Imagine my surprise when in the spring of 1939 a letter arrived at my house inviting me to dinner at the Old Chancellery with the world’s most reviled man, Adolf Hitler.” I don’t carry a camera in my hometown of Chapel Hill, and even though my cellphone contains a camera, I use it only for snapshots. Naturally, there were moments when I wished I had a camera with me. Once, while walking in my neighborhood at twilight, I felt a strange rush of energy in the air, and, suddenly, no more than twenty feet away, a majestically antlered whitetail buck soared over a garden fence and hurtled down the dimming street. Yet even as it was happening—this unexpectedly preternatural moment—I tried to imagine it as a photograph. That’s how we’ve been taught to think. “Oh, I wish I’d had a camera!” But that presumes I would have been prepared to capture the moment—instead of being startled by it. Yet being startled by beauty is a uniquely, and all too rare, human gift. The photograph comes later, when I journey back from astonishment and begin to fiddle with my camera.

I don’t carry a camera in my hometown of Chapel Hill, and even though my cellphone contains a camera, I use it only for snapshots. Naturally, there were moments when I wished I had a camera with me. Once, while walking in my neighborhood at twilight, I felt a strange rush of energy in the air, and, suddenly, no more than twenty feet away, a majestically antlered whitetail buck soared over a garden fence and hurtled down the dimming street. Yet even as it was happening—this unexpectedly preternatural moment—I tried to imagine it as a photograph. That’s how we’ve been taught to think. “Oh, I wish I’d had a camera!” But that presumes I would have been prepared to capture the moment—instead of being startled by it. Yet being startled by beauty is a uniquely, and all too rare, human gift. The photograph comes later, when I journey back from astonishment and begin to fiddle with my camera. For decades, neuroscientists have thought that the brain learns by changing how neurons are connected to one another. As new information and experiences alter how neurons communicate with each other and change their collective activity patterns, some synaptic connections are made stronger while others are made weaker. This process of

For decades, neuroscientists have thought that the brain learns by changing how neurons are connected to one another. As new information and experiences alter how neurons communicate with each other and change their collective activity patterns, some synaptic connections are made stronger while others are made weaker. This process of  It’s been nearly two decades since I finished my undergraduate degree, and my memories of my philosophy major, like most things associated with one’s early adulthood, are hazy at best.

It’s been nearly two decades since I finished my undergraduate degree, and my memories of my philosophy major, like most things associated with one’s early adulthood, are hazy at best. B

B We all want

We all want GILLIAN CARNEGIE’S current show at

GILLIAN CARNEGIE’S current show at  In Plato’s dialogue Symposium, seven varied speeches are made on the meaning of love at an all-male drinking party set in ancient Athens in

In Plato’s dialogue Symposium, seven varied speeches are made on the meaning of love at an all-male drinking party set in ancient Athens in  In the early months of 1966, whenever Paul McCartney sat down at a piano, wherever it was, he would start tinkering with a song he called “Miss Daisy Hawkins.” From the moment he found its first five syllabic notes, the song seems to have found its themes: loneliness, futility, the end of life. McCartney was twenty-three. Without discussing it, both John Lennon and Paul came back from their break with songs about death, written from a detached, omniscient perspective.

In the early months of 1966, whenever Paul McCartney sat down at a piano, wherever it was, he would start tinkering with a song he called “Miss Daisy Hawkins.” From the moment he found its first five syllabic notes, the song seems to have found its themes: loneliness, futility, the end of life. McCartney was twenty-three. Without discussing it, both John Lennon and Paul came back from their break with songs about death, written from a detached, omniscient perspective. Sixty years ago, a debate raged between two titans of evolutionary biology that came to be

Sixty years ago, a debate raged between two titans of evolutionary biology that came to be