The Why of Coyote

I was asked about Anglos taking over

Native American mythic figures. I have

also been told that Anglos have a naive and

sentimental view of Native Americans.

My response is that Coyote and I

are not playing “feel good” games here.

We are doing some hard work rethinking

the mythic foundations of our culture.

I know many think myth is something we

have outgrown, that we should look to

technology and rationality as guides

out of our predicament.

I happen to believe that’s a myth, which

may be a good and useful myth, but when we

don’t recognize a myth for what it is we are

in danger of being fundamentalists, spending

our energy defensively protecting the literal

truth of our myth and ignoring the consequences

of our collective, human, willful ignorance of

what is real.

I find Coyote, the Trickster, an incarnation

of all in me that is not rational, that still screams

to be alive in a technically suffocating culture.

I find Coyote to be a magical animal, an incarnation

of what I experience in myself as earthy spirituality.

A revolution is going on against the technological,

rational, and corporate sentiments that dominate

our culture. It is a revolution saying “No!” at a

primal, spiritual, life-and-death, wounded animal

level. The proof of our deadliness, of our rational,

technical, corporate culture is the depression that

greets us when we open the morning paper or

listen to the evening news. We feel that it’s all to late,

that greed and denial are at the controls. Well, we’re

all going to die anyway, so we might as well have fun

whacking a few myths as we go. It’s a different path

we’re trying to discover again. We think it’s a path to

being whole, finding our animal nature. So I talk to

my animal nature and it responds with healing

intelligence. I invite you;

discuss things with your own animal nature

and see if you find a wise voice you have overlooked.

by Webster Kitchell

from Coyote Says

Skinner House Books, 1996

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

It must be emphasised that until recently, the story of African philosophy has been synonymous with unjustified denial, exclusion, controversy, and scepticism. Thus, within the first chapter, Mungwini carefully provides an excellent cartographic analysis of the discipline of African philosophy before exposing some of the debates, challenges, disagreements and controversies that have historically characterised and shaped the development and current trends in African philosophy, particularly the famous “critique of ethnophilosophy” that was sparked by Paulin J. Hountondji. While he strives to “lay out its [African philosophy’s] methodological and epistemological foundations as an enterprise” (17), Mungwini makes an important entry into African philosophy. He identifies the kind of self-scepticism and hesitancy to affirm self-identity that impedes the progress of African philosophy owing to the critique of ethnophilosophy, unlike the “multiplicity of views and divisions that have characterised Western philosophy as a tradition” (14; see also, 18). Essentially, Mungwini alerts the reader to some of the consequences of the unintended exclusionary effects which the traditional critique of ethno-philosophy has had on African philosophical traditions, notwithstanding its encouragement of critical discourse on African philosophy through rejection of what Mungwini sees as unanimism and extraversion (24). Indeed, the critique of ethno-philosophy can be acknowledged for denying a collective philosophy that is always oriented towards satisfying the outside world, although, its putative implications on African philosophy is something that cannot be taken for granted, and Mungwini should be credited for his cautionary approach to it.

It must be emphasised that until recently, the story of African philosophy has been synonymous with unjustified denial, exclusion, controversy, and scepticism. Thus, within the first chapter, Mungwini carefully provides an excellent cartographic analysis of the discipline of African philosophy before exposing some of the debates, challenges, disagreements and controversies that have historically characterised and shaped the development and current trends in African philosophy, particularly the famous “critique of ethnophilosophy” that was sparked by Paulin J. Hountondji. While he strives to “lay out its [African philosophy’s] methodological and epistemological foundations as an enterprise” (17), Mungwini makes an important entry into African philosophy. He identifies the kind of self-scepticism and hesitancy to affirm self-identity that impedes the progress of African philosophy owing to the critique of ethnophilosophy, unlike the “multiplicity of views and divisions that have characterised Western philosophy as a tradition” (14; see also, 18). Essentially, Mungwini alerts the reader to some of the consequences of the unintended exclusionary effects which the traditional critique of ethno-philosophy has had on African philosophical traditions, notwithstanding its encouragement of critical discourse on African philosophy through rejection of what Mungwini sees as unanimism and extraversion (24). Indeed, the critique of ethno-philosophy can be acknowledged for denying a collective philosophy that is always oriented towards satisfying the outside world, although, its putative implications on African philosophy is something that cannot be taken for granted, and Mungwini should be credited for his cautionary approach to it. When I first moved to Salzburg, I rented a place in a small 19th century building around the corner from the medieval Linzer Gasse, where Renaissance polymath Dr. Paracelsus was buried, and where Expressionist poet Georg Trakl had worked in a pharmacy. The flat had high ceilings, tall windows, a lovely old herringbone wooden floor, and blinding white walls just waiting for works of graphic impact to give them a semblance of meaning. I couldn’t afford a painting, but in a nearby poster shop—they were popular in those pre-online days—I flipped through hundreds of art reproductions, hoping to find an image deserving of those pristine walls. Only one poster fit the bill: a László Moholy-Nagy collage from 1922: Kinetisch-Konstruktives System (KKS).

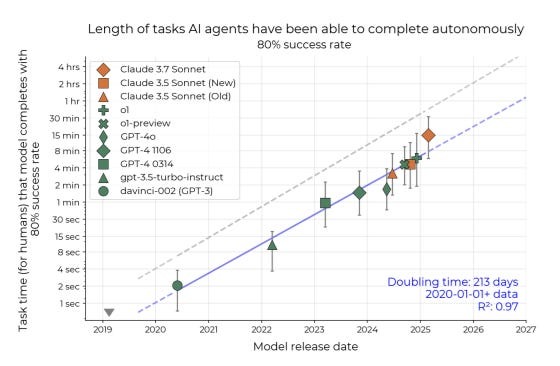

When I first moved to Salzburg, I rented a place in a small 19th century building around the corner from the medieval Linzer Gasse, where Renaissance polymath Dr. Paracelsus was buried, and where Expressionist poet Georg Trakl had worked in a pharmacy. The flat had high ceilings, tall windows, a lovely old herringbone wooden floor, and blinding white walls just waiting for works of graphic impact to give them a semblance of meaning. I couldn’t afford a painting, but in a nearby poster shop—they were popular in those pre-online days—I flipped through hundreds of art reproductions, hoping to find an image deserving of those pristine walls. Only one poster fit the bill: a László Moholy-Nagy collage from 1922: Kinetisch-Konstruktives System (KKS). In the decade that I have been working on AI, I’ve watched it grow from a tiny academic field to arguably the most important economic and geopolitical issue in the world. In all that time, perhaps the most important lesson I’ve learned is this: the progress of the underlying technology is inexorable, driven by forces too powerful to stop, but the way in which it happens—the order in which things are built, the applications we choose, and the details of how it is rolled out to society—are eminently possible to change, and it’s possible to have great positive impact by doing so. We can’t stop the bus, but we can steer it. In the past I’ve written about the importance of deploying AI in a way that is

In the decade that I have been working on AI, I’ve watched it grow from a tiny academic field to arguably the most important economic and geopolitical issue in the world. In all that time, perhaps the most important lesson I’ve learned is this: the progress of the underlying technology is inexorable, driven by forces too powerful to stop, but the way in which it happens—the order in which things are built, the applications we choose, and the details of how it is rolled out to society—are eminently possible to change, and it’s possible to have great positive impact by doing so. We can’t stop the bus, but we can steer it. In the past I’ve written about the importance of deploying AI in a way that is  I have been promising/threatening for a while to cover degrowth, and thanks to a

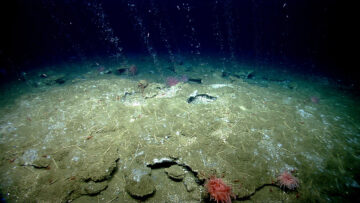

I have been promising/threatening for a while to cover degrowth, and thanks to a  Buried in the deepest darkness underground, eating strange food, playing with the laws of thermodynamics and living on unrelatably long timescales, intraterrestrials have remained largely remote and aloof from humans. However, the microbes that dwell in the deep subsurface biosphere affect our lives in innumerable ways.

Buried in the deepest darkness underground, eating strange food, playing with the laws of thermodynamics and living on unrelatably long timescales, intraterrestrials have remained largely remote and aloof from humans. However, the microbes that dwell in the deep subsurface biosphere affect our lives in innumerable ways. The most conspicuous mark of Renata Adler’s style is its abundance of commas. In her two novels, Speedboat (1976) and Pitch Dark (1983), there are a few sentences that edge on the absurd: “For some time, Leander had spoken, on the phone, of a woman, a painter, whom he had met, one afternoon, outside the gym, and whom he was trying to introduce, along with Simon, into his apartment and his life.” A critic tallied it up, counting “40 words and ten commas—Guinness Book of World Records?” Each of those commas had its grammatical defense, but Adler’s style did not comply with the usual standards of fluent prose. She cordoned off phrases, such as “on the phone,” that other writers would just run through. One reader, responding to a 1983 New York magazine profile of Adler, wrote in a letter to the editor, “If the examples of Renata Adler’s writing … are typical, Miss Adler will never make it to the road. The way is ‘jarringly, piece by piece, line by line, and without interruption’ blocked by commas.” The reader was quoting one of Adler’s own comma-laden critical phrases against her. The editors titled the letter “Comma Wealth.”

The most conspicuous mark of Renata Adler’s style is its abundance of commas. In her two novels, Speedboat (1976) and Pitch Dark (1983), there are a few sentences that edge on the absurd: “For some time, Leander had spoken, on the phone, of a woman, a painter, whom he had met, one afternoon, outside the gym, and whom he was trying to introduce, along with Simon, into his apartment and his life.” A critic tallied it up, counting “40 words and ten commas—Guinness Book of World Records?” Each of those commas had its grammatical defense, but Adler’s style did not comply with the usual standards of fluent prose. She cordoned off phrases, such as “on the phone,” that other writers would just run through. One reader, responding to a 1983 New York magazine profile of Adler, wrote in a letter to the editor, “If the examples of Renata Adler’s writing … are typical, Miss Adler will never make it to the road. The way is ‘jarringly, piece by piece, line by line, and without interruption’ blocked by commas.” The reader was quoting one of Adler’s own comma-laden critical phrases against her. The editors titled the letter “Comma Wealth.” Not every rich person is rolling up in a Lamborghini or dripping in designer logos. If anything, the truly wealthy often move through the world a little quieter, but a lot more confidently. Look closely enough, and the signs are everywhere. Behavior is one of the first giveaways. Educator and content creator Dani Payne

Not every rich person is rolling up in a Lamborghini or dripping in designer logos. If anything, the truly wealthy often move through the world a little quieter, but a lot more confidently. Look closely enough, and the signs are everywhere. Behavior is one of the first giveaways. Educator and content creator Dani Payne  You can want different things from a university—superlative basketball, an arts center, competent instruction in philosophy or physics, even a cure for cancer. No wonder these institutions struggle to keep everyone happy. And everyone isn’t happy. The Trump Administration has effectively declared open war on higher education, targeting it with deep cuts to federal grant funding. University presidents are alarmed, as are faculty members, and anyone who cares about the university’s broader role.

You can want different things from a university—superlative basketball, an arts center, competent instruction in philosophy or physics, even a cure for cancer. No wonder these institutions struggle to keep everyone happy. And everyone isn’t happy. The Trump Administration has effectively declared open war on higher education, targeting it with deep cuts to federal grant funding. University presidents are alarmed, as are faculty members, and anyone who cares about the university’s broader role. A century ago, one of the richest men in the world decided to wade into the public sphere by throwing his weight behind a series of cuts that would reach into every corner of American life. The president of the day, sensing early support for these reforms and not wishing to be left behind, jumped on board with impulsive zeal, demanding that all federal offices implement the cutbacks with immediate effect.

A century ago, one of the richest men in the world decided to wade into the public sphere by throwing his weight behind a series of cuts that would reach into every corner of American life. The president of the day, sensing early support for these reforms and not wishing to be left behind, jumped on board with impulsive zeal, demanding that all federal offices implement the cutbacks with immediate effect.

The legal doctrine of “habeas corpus,” a Latin phrase that has its

The legal doctrine of “habeas corpus,” a Latin phrase that has its  What’s distinctive about humans is that homo sapiens domesticated themselves. We are self-domesticated apes. Anthropologist Brian Hare characterizes recent human evolution (Late Pleistocene) as “Survival of the Friendliest”, arguing that in our self-domestication we favored prosociality — the tendency to be friendly, cooperative, and empathetic. We chose the most cooperative, the least aggressive, the less bullying types, and that trust in others resulted in greater prosperity, which in turn spread neoteny genes, and other domestication traits, into our populations.

What’s distinctive about humans is that homo sapiens domesticated themselves. We are self-domesticated apes. Anthropologist Brian Hare characterizes recent human evolution (Late Pleistocene) as “Survival of the Friendliest”, arguing that in our self-domestication we favored prosociality — the tendency to be friendly, cooperative, and empathetic. We chose the most cooperative, the least aggressive, the less bullying types, and that trust in others resulted in greater prosperity, which in turn spread neoteny genes, and other domestication traits, into our populations. Against the backdrop of a cold white room, Iris Apfel’s yellow outfit, which she wore on the occasion of her hundredth birthday, sings its own joyous song. Both here and elsewhere, Apfel, an artist and fashion designer, often paired gorgeous things sensually by color and texture, rather than by invoking some obvious theory or idea. She was not afraid to wear a yellow tulle coat with yellow silk pants (which she designed herself in collaboration with H&M). She celebrated yellow vivaciously; she took up space with yellow. With her arms raised in this picture, she looks like some sort of bishop or religious figure. Her open palms throw spectral glitter upon us. A spiritual icon. Just by looking at her, I feel her upturned palms manifesting my dreams.

Against the backdrop of a cold white room, Iris Apfel’s yellow outfit, which she wore on the occasion of her hundredth birthday, sings its own joyous song. Both here and elsewhere, Apfel, an artist and fashion designer, often paired gorgeous things sensually by color and texture, rather than by invoking some obvious theory or idea. She was not afraid to wear a yellow tulle coat with yellow silk pants (which she designed herself in collaboration with H&M). She celebrated yellow vivaciously; she took up space with yellow. With her arms raised in this picture, she looks like some sort of bishop or religious figure. Her open palms throw spectral glitter upon us. A spiritual icon. Just by looking at her, I feel her upturned palms manifesting my dreams. T

T