Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

David Horowitz (1939 – 2025) Political Writer and Activist

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Mike Peters (1959 – 2025) Musician

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

A user-friendly opera about Steve Jobs powers up at the Kennedy Center

Michael Brodeur in The Washington Post:

“The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs” doesn’t so much begin as start up. When the first flourish of composer Mason  Bates’s score rings out — a wobbly, synthetic chime of sorts — you’d swear someone had pressed a power button in the orchestra pit. On Friday evening at the Kennedy Center, the Washington National Opera opened its production of Bates’s opera with a libretto by Mark Campbell — its tenth since the opera’s premiere at Santa Fe Opera in 2017. Guest conductor Lidiya Yankovskaya led the Washington National Opera Orchestra and Chorus in this revival of Tomer Zvulun’s production, here directed by Rebecca Herman.

Bates’s score rings out — a wobbly, synthetic chime of sorts — you’d swear someone had pressed a power button in the orchestra pit. On Friday evening at the Kennedy Center, the Washington National Opera opened its production of Bates’s opera with a libretto by Mark Campbell — its tenth since the opera’s premiere at Santa Fe Opera in 2017. Guest conductor Lidiya Yankovskaya led the Washington National Opera Orchestra and Chorus in this revival of Tomer Zvulun’s production, here directed by Rebecca Herman.

The set is an austere arrangement of scaffolding and screens, a versatile scheme that shuttles viewers through time and space: from the humble garage workshop where Jobs and Steve Wozniak first tinkered with their clunky prototypes in the early 1970s, to the depths of Yosemite National Park in the early 1990s, to a tech conference in San Francisco where the iPhone was launched in 2007 — though not necessarily in that order.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

(Don’t Be Squeamish) The Unlikely Cure for a Gut Disease

Gabriel Weston in Undark Magazine:

The most immutable fact they teach you in medical school is that anatomy is the absolute bedrock of surgery. As an eager young surgical intern, I often got doused in my patients’ vomit and shit. I tried to see the clinical bright side: Maybe the old man’s feces contained blood or the teen who had barfed up the offending Tylenol would avoid a liver transplant. Otherwise, the contents of normal guts were of less interest.

The most immutable fact they teach you in medical school is that anatomy is the absolute bedrock of surgery. As an eager young surgical intern, I often got doused in my patients’ vomit and shit. I tried to see the clinical bright side: Maybe the old man’s feces contained blood or the teen who had barfed up the offending Tylenol would avoid a liver transplant. Otherwise, the contents of normal guts were of less interest.

Back then, we were taught that the sole purpose of the gastrointestinal tract was to extract nutrients from food. What I didn’t expect, after practicing as a surgeon myself for over 20 years, is that what we think we know about human anatomy is actually changing all the time and that our bodies are more varied, more full of wonders and magical revelations, than we could ever have imagined.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

On the Brink?

Tariq Ali in Sidecar:

India and Pakistan are preparing for war. The casus belli is, once again, occupied Kashmir. Control over this disputed region has since 1947 been the main obstacle to normalising relations between the two states. On 21 April, a group of Kashmiri militants targeted and killed 26 tourists enjoying the beauty of Pahalgam’s flower-filled meadows, crystal streams and snow-capped mountains; responsibility for the attack was claimed and then quickly disavowed by a little-known organization called the ‘Resistance Front’. This was a particular affront to Narendra Modi (whose record includes presiding, as Chief Minister, over the slaughter of an estimated 2,000 civilians in the 2002 Gujarat massacre, and long a defender of anti-Muslim pogroms). A far-right Hindu nationalist now in his third term as India’s Prime Minister, Modi had previously declared that there was no longer any serious Kashmir problem. His final solution – revoking Kashmir’s autonomous status in 2019 – had succeeded.

Nothing justifies the slaughter of the Pahalgam holidaymakers, and vanishingly few Kashmiri or Indian Muslims would support actions of this sort. But historical context is necessary to understand the overall situation in the province. Even Israel has a Ha’aretz. Not India. Kashmir remains an untouchable subject. This Muslim-majority province has never been allowed to determine its own fate, as promised by Congress leaders at the time of Independence. Instead, it was partitioned between the new republics of India and Pakistan after a short war in which the British commander of the Pakistan Army refused to agree to its use, leaving a ragtag force to face off against India’s regular troops. That well-known pacifist, Mahatma Gandhi, blessed the Indian invasion. Articles 370 and 35A of the Indian Constitution were supposed to guarantee Kashmir’s special status, not least by forbidding non-Kashmiris the right to buy property and settle there. This was combined with brutal repression of any stirrings of discontent, turning Kashmir into a police state with military units never too far away.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Intellectual Historians Confront the Present

Leonard Benardo interviews Daniel Steinmetz-Jenkins over at The Ideas Letter:

Leonard Benardo: I thought I would begin by asking you why you think the field of Intellectual History has made such an unanticipated resurgence in recent years. At some point, only a decade or so ago, it was seemingly on the brink of turning moribund, and if you were interested in the area you would have been well advised to go to law school instead. Jobs were scarce. What happened? What were the triggers that reignited the field? How do you account for the turn in terms of structure, ideology, and otherwise?

Daniel Steinmetz-Jenkins: I do think intellectual history has been revitalized but primarily outside the confines of the academy. Of course, there are plenty of great intellectual historians currently writing, but the field has experienced the same fate as the general history profession in terms of the so-called academic jobs crisis that has significantly deepened since 2016. Even if one was to be admitted to Harvard, Yale, or Princeton to study intellectual history, it is probably unlikely that doing so would lead to a tenure-track job. I think there is a hesitancy for professors at even these places to take on students as they know there is a good chance it will not result in a tenure-track offer. Whenever one of my students at Wesleyan says they want to go to grad school to become a history professor, I feel an ethical obligation to explain to them the risk involved in that decision. In terms of your comment about law school, I encourage them to do a PhD/JD so that if a history job doesn’t materialize, they at least have the fallback option of a law career or even becoming a law professor. Of course, some students are privileged enough so as not to have to worry about the risk, which means that we might end up with a profession, in a generation, dominated by a particular class.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Brian Eno’s Theory of Democracy

Henry Farrell over at his substack Programmable Mutter:

The back story to this post doesn’t start with Brian Eno. Back in 1991, the political scientist Adam Przeworski published a book, Democracy and the Market. Most of the book was about the democratic transition in Central and Eastern Europe, and it was very good as best as I can judge these things. But the first chapter was much, much better than very good. It laid out a brief theory of democracy that reshaped the ways in which political scientists think about it.

Przeworski’s theory starts from a simple seeming claim: that “democracy is a system in which parties lose elections.” It then uses a combination of game theory and informal argument to lay out the implications. If we assume (as Przeworski assumes) that parties and political decision makers are self-centered, why would the ruling party ever accept that they had lost and relinquish control of government? Przeworski argues that it must somehow be in their self-interest to so. He argues that they will admit defeat if they see that the alternative is worse, and (this is crucial) because democracy generates sufficient uncertainty about the future that they believe they might win in some future election. They know that they will hurt their interests if they refuse to give in, and they have some (unquantifiable but real) prospect of coming back into power again. Democracy, then, will be stable so long as the expectation of costs and the uncertainty of the future give the losers sufficient incentive to accept that they have lost.

This is a more beautiful idea than I am able to explain in a brief post, and certainly much more beautiful than any argument I will ever come up with myself. It compresses a vast and turbid system of enmeshed ambitions and behaviors into a deceptively simple nine word thesis

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sunday Poem

Me he perdido muchas veces por el mar

I I’ve lost myself many times in the sea

Ghazal for Lorca

Had Lorca been in India, he would have been lost in the sea of courtesans

Not the coquetry of Andalusian women, but dusky moaning courtesans

Had Lorca been in Lahore for versos, he would have visited the Lahore Fort,

the duende and Dionysian blood wedding of a yearning courtesan

Had Lorca met me in the surreal setting across the Taj Mahal, we would

have penned Rubaiyat, an assembly of tears, simmering courtesans!

Had Lorca searched for jasmine and vendors around the Royal Mosque

I would have preferred to sleep and supplicate with a courtesan,

Had Lorca instead of Basilica, chosen the shrine of a saint in Lahore,

the Genile, grooved by tobaccos, a puff of love with my courtesan,

Had I been there where Lora was martyred, I would have grieved long

till churches had stopped tolling; better die embracing a courtesan,

Had Lorca and Agha Shahid encountered and roamed for Rekhta in Kashmir,

Rizwan would have breached borders, exporting ghazals with courtesans.

by Prof.Dr. Rizwan Akhtar

Institute of English Studies

Punjab University

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday, May 2, 2025

Testing AI’s GeoGuessr Genius

Scott Alexander at Astral Codex Ten:

Last week, Kelsey Piper claimed that o3 – OpenAI’s latest ChatGPT model – could achieve seemingly impossible feats in GeoGuessr. She gave it this picture:

…and with no further questions, it determined the exact location (Marina State Beach, Monterey, CA).

How? She linked a transcript where o3 tried to explain its reasoning, but the explanation isn’t very good. It said things like:

Tan sand, medium surf, sparse foredune, U.S.-style kite motif, frequent overcast in winter … Sand hue and grain size match many California state-park beaches. California’s winter marine layer often produces exactly this thick, even gray sky.

Commenters suggested that it was lying. Maybe there was hidden metadata in the image, or o3 remembered where Kelsey lived from previous conversations, or it traced her IP, or it cheated some other way.

I decided to test the limits of this phenomenon.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Ways to Cut Your Risk of Stroke, Dementia and Depression All at Once

Nina Agrawal in the New York Times:

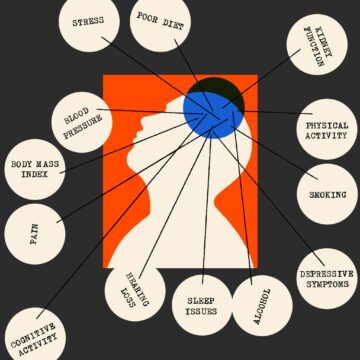

New research has identified 17 overlapping factors that affect your risk of stroke, dementia and late-life depression, suggesting that a number of lifestyle changes could simultaneously lower the risk of all three.

New research has identified 17 overlapping factors that affect your risk of stroke, dementia and late-life depression, suggesting that a number of lifestyle changes could simultaneously lower the risk of all three.

Though they may appear unrelated, people who have dementia or depression or who experience a stroke also often end up having one or both of the other conditions, said Dr. Sanjula Singh, a principal investigator at the Brain Care Labs at Massachusetts General Hospital and the lead author of the study. That’s because they may share underlying damage to small blood vessels in the brain, experts said.

Some of the risk factors common to the three brain diseases, including high blood pressure and diabetes, appear to cause this kind of damage. Research suggests that at least 60 percent of strokes, 40 percent of dementia cases and 35 percent of late-life depression cases could be prevented or slowed by controlling risk factors.

“Those are striking numbers,” said Dr. Stephanie Collier, director of education in the division of geriatric psychiatry at McLean Hospital in Massachusetts. “If you can really optimize the lifestyle pieces or the modifiable pieces, then you’re at such a higher likelihood of living life without disability.”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

“Godfather of AI” Geoffrey Hinton shares predictions for future of AI

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Robert Crumb and Dan Nadel with Naomi Fry

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

A Modern Counterrevolution

Bernard E. Harcourt in The Ideas Letter:

In a blizzard of executive orders and emergency declarations, President Donald Trump has taken a hatchet to the American government and the global order. He is wrecking the administrative state, shuttering entire agencies and departments, laying off federal workers, firing inspectors general. He is deporting permanent residents for speech protected by the First Amendment, revoking visas from international students, sending immigrants to the military camp at Guantánamo Bay and a mega-prison in El Salvador, and trying to eliminate birthright citizenship. He is defunding research universities and attacking the legal profession. He is threatening draconian tariffs on the country’s closest allies and neighbors, demeaning their leaders, and pulling the United States out of longstanding international commitments. Every day, he launches another unprecedented offensive or changes course; he creates ambiguity and fuels confusion, leaving his critics to second-guess themselves while giving himself cover.

He remains extremely popular with his base, even if his overall ratings have dropped to record lows. His critics, though, attack him six ways from Sunday. They call him a fascist, an authoritarian, a tyrant, the kleptocratic tool of tech billionaires, a profiteer, a reality-TV impostor, the embodiment of toxic masculinity, a bully. Yet none of these labels fully captures the scope or the coherence of what is happening in the U.S. today. These diagnoses focus too much on the individual, and this is an individual who, like a virtuoso illusionist, keeps his audience mesmerized by the spectacle but distracted from what is really going on. The radical developments underway must be placed in deeper perspective.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Working at Krispy Kreme

Kate Durbin at The Baffler:

My favorite thing to do at Krispy Kreme to stave off the boredom is stack the donuts on top of each other and then squish them down into a “sandwich.” When they are hot, they flatten in an extreme way. I can get about twelve in the pile before things get messy. Some days, this donut sandwich is all I eat, other than maybe one other thing, a giant slice of pizza from Sbarro or orange chicken from Panda Express in the mall across the vast parking lot, which I pay for with my meager tip money. I also drink excessive amounts of the whole chocolate milk we sell. This anorexic, sugary diet means I weigh just under 110 pounds and am always jittery.

My favorite thing to do at Krispy Kreme to stave off the boredom is stack the donuts on top of each other and then squish them down into a “sandwich.” When they are hot, they flatten in an extreme way. I can get about twelve in the pile before things get messy. Some days, this donut sandwich is all I eat, other than maybe one other thing, a giant slice of pizza from Sbarro or orange chicken from Panda Express in the mall across the vast parking lot, which I pay for with my meager tip money. I also drink excessive amounts of the whole chocolate milk we sell. This anorexic, sugary diet means I weigh just under 110 pounds and am always jittery.

I get home at night bone-exhausted. Peel my shoes from my swollen feet, dirty white Vans I got at Journeys in the mall, skater shoes that reek of sweat but also sweetness. The donut smell baked into the shoe’s material. Years later it will still be there when I finally throw those shoes away.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

As Neighbors Start Disappearing

Lawrence Weschler at Wondercabinet:

For hard as it still may be to believe, let alone process, in barely one hundred days we have already fallen into a form of governance in which legally resident individuals (currently by and large immigrants of one sort or another—mothers, fathers, students with entirely current green cards or asylum claims—but with every indication that such tactics will presently be getting extended to full-fledged citizens as well) are literally being spirited off the streets by masked men in unmarked cars and, without the slightest due process or the most tenuous access to any sort of recourse, whisked off to prisons, both at home and abroad, seemingly beyond the sanction of any sort of judicial oversight (the rulings of judges flagrantly ignored and the judges themselves now starting to get subjected to arbitrary arrest as well simply for even having expressed them), the legislative branch cowed into impotence by the abject servitude of its barely majority party, the executive branch a whipsaw of whims and tantrums, with no end in sight.

For hard as it still may be to believe, let alone process, in barely one hundred days we have already fallen into a form of governance in which legally resident individuals (currently by and large immigrants of one sort or another—mothers, fathers, students with entirely current green cards or asylum claims—but with every indication that such tactics will presently be getting extended to full-fledged citizens as well) are literally being spirited off the streets by masked men in unmarked cars and, without the slightest due process or the most tenuous access to any sort of recourse, whisked off to prisons, both at home and abroad, seemingly beyond the sanction of any sort of judicial oversight (the rulings of judges flagrantly ignored and the judges themselves now starting to get subjected to arbitrary arrest as well simply for even having expressed them), the legislative branch cowed into impotence by the abject servitude of its barely majority party, the executive branch a whipsaw of whims and tantrums, with no end in sight.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday Poem

All About the Blues

smiling, nodding in affirmation – dry, chalky blue

of the sky brushing itself one way, then another,

a place in which I could easily drown.

by Greg Watson

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Thursday, May 1, 2025

A reviewer hangs with Bono for five hundred pages

Matthew Shipe in The Common Reader:

The lead singer and primary lyricist of the long-running rock band U2, Bono has never exactly been the shy type. Outside of Elvis posing with Nixon, no rock star has seemed so comfortable posing with so many politicians, and Bono has perhaps set the record for the most Rock ’n’ Roll Hall of Fame induction speeches given.3 A preacherly ambition propels Bono’s memoir, Surrender: 40 Songs, One Story, as the book chronicles U2’s forty-odd-year career, and the book’s impact hinges on your openness to Bono’s expansiveness. While no fruit is thrown at rock royalty, Surrender as a whole offers a smart and charmingly self-deprecating portrait of Bono and his three friends from Dublin as they propel themselves from scruffy post-punk band to one of the last of the great rock ’n’ roll acts, one of the few bands from their era that can stand with the Stones and the McCartneys in the cavernous sports arenas around the world. If a talking head is needed to wax poetic on America, rock ’n’ roll, debt relief, religion, sex, life, death—I am sure he has an opinion on cross-stitching—Bono is the person to turn to.

The lead singer and primary lyricist of the long-running rock band U2, Bono has never exactly been the shy type. Outside of Elvis posing with Nixon, no rock star has seemed so comfortable posing with so many politicians, and Bono has perhaps set the record for the most Rock ’n’ Roll Hall of Fame induction speeches given.3 A preacherly ambition propels Bono’s memoir, Surrender: 40 Songs, One Story, as the book chronicles U2’s forty-odd-year career, and the book’s impact hinges on your openness to Bono’s expansiveness. While no fruit is thrown at rock royalty, Surrender as a whole offers a smart and charmingly self-deprecating portrait of Bono and his three friends from Dublin as they propel themselves from scruffy post-punk band to one of the last of the great rock ’n’ roll acts, one of the few bands from their era that can stand with the Stones and the McCartneys in the cavernous sports arenas around the world. If a talking head is needed to wax poetic on America, rock ’n’ roll, debt relief, religion, sex, life, death—I am sure he has an opinion on cross-stitching—Bono is the person to turn to.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

A Spring in Every Kitchen

Charles C. Mann in The New Atlantis:

For as long as our species has lived in settled communities, we have struggled to provide ourselves with water. If modern agriculture, the subject of the previous article in this series, is a story of innovation and progress, the water supply has all too often been the opposite: a tale of stagnation and apathy. Even today, about two billion people, most of them in poor, rural areas, do not have a reliable supply of clean water — potable water, in the jargon of water engineers. Bad water leads to the death every year of about a million people. In terms of its immediate impact on human lives, water is the world’s biggest environmental problem and its worst public health problem — as it has been for centuries.

For as long as our species has lived in settled communities, we have struggled to provide ourselves with water. If modern agriculture, the subject of the previous article in this series, is a story of innovation and progress, the water supply has all too often been the opposite: a tale of stagnation and apathy. Even today, about two billion people, most of them in poor, rural areas, do not have a reliable supply of clean water — potable water, in the jargon of water engineers. Bad water leads to the death every year of about a million people. In terms of its immediate impact on human lives, water is the world’s biggest environmental problem and its worst public health problem — as it has been for centuries.

On top of that, fresh water is surprisingly scarce. A globe shows blue water covering our world. But that picture is misleading: 97.5 percent of the Earth’s water is salt water — corrosive, even toxic. The remaining 2.5 percent is fresh, but the great bulk of that is unreachable, either because it is locked into the polar ice caps, or because it is diffused in porous rock deep beneath the surface.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Grant Sanderson: But what is quantum computing?

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.