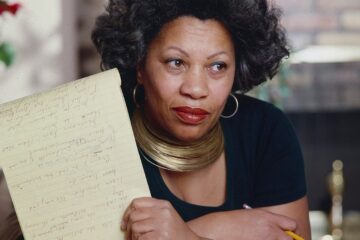

Dana Williams in Slate:

I first interviewed Toni Morrison about her work as a book editor in September 2005, in her office at Princeton. Though our meeting was scheduled for late afternoon, I took an early train from Washington to make sure I could situate myself in West College—which would be renamed Morrison Hall in 2017—while I rehearsed my carefully crafted questions. I was struck by the quiet gravity of the building and its hallways: sunlight slanting through stately windows, the scent of old books and weathered wood lingering in the air. The fact that I was about to sit across from a literary giant—celebrated worldwide for her novels yet virtually unknown for her groundbreaking work as an editor at Random House—was not lost on me.

I first interviewed Toni Morrison about her work as a book editor in September 2005, in her office at Princeton. Though our meeting was scheduled for late afternoon, I took an early train from Washington to make sure I could situate myself in West College—which would be renamed Morrison Hall in 2017—while I rehearsed my carefully crafted questions. I was struck by the quiet gravity of the building and its hallways: sunlight slanting through stately windows, the scent of old books and weathered wood lingering in the air. The fact that I was about to sit across from a literary giant—celebrated worldwide for her novels yet virtually unknown for her groundbreaking work as an editor at Random House—was not lost on me.

My anxiousness reminded me that I had often wondered what it must have been like for authors to have the Toni Morrison as their editor. When the writer John A. McCluskey Jr. first met Morrison in 1971, she had published only The Bluest Eye. McCluskey, not yet 30 years old, saw her not as the Pulitzer Prize–winning Nobel laureate she would become, but as a fellow Ohio writer looking to make her mark as an editor. She was also, he discovered two years later, the kind of person who made a fuss when she learned that McCluskey’s wife and son were in the car waiting while they had their first author-editor meeting at the Random House offices on East 50th Street to discuss his first novel, Look What They Done to My Song. Whatever else was on her schedule would have to wait. She wanted to greet Audrey and Malik. It was the least she could do since they had joined McCluskey for the drive from the Midwest to Manhattan.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

S

S Dear Reader,

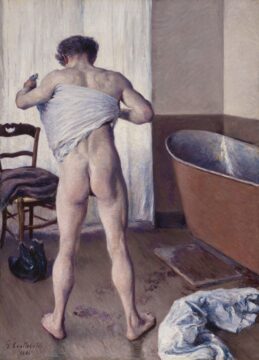

Dear Reader, Some years ago, I saw a painting that knocked my sense of the sexes sideways. It was an 1884 work by an Impressionist named Gustave Caillebotte of a nude figure emerging from the bath — the same trope that Degas or Bonnard so often employ because it allows you to observe a woman’s naked body in motion, absorbed in a private ritual replete with sensual pleasure.

Some years ago, I saw a painting that knocked my sense of the sexes sideways. It was an 1884 work by an Impressionist named Gustave Caillebotte of a nude figure emerging from the bath — the same trope that Degas or Bonnard so often employ because it allows you to observe a woman’s naked body in motion, absorbed in a private ritual replete with sensual pleasure. On a weekend in mid-May, a clandestine mathematical conclave convened. Thirty of the world’s most renowned mathematicians traveled to Berkeley, Calif., with some coming from as far away as the U.K. The group’s members faced off in a showdown with

On a weekend in mid-May, a clandestine mathematical conclave convened. Thirty of the world’s most renowned mathematicians traveled to Berkeley, Calif., with some coming from as far away as the U.K. The group’s members faced off in a showdown with  The rapidly escalating military conflict between Israel and Iran represents a clash of ambitions. Iran seeks to become a nuclear power, and Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu longs to be remembered as the Israeli leader who categorically thwarted Iran’s nuclear program, which he views as an existential threat to Israel’s survival. Both dreams are as misguided as they are dangerous.

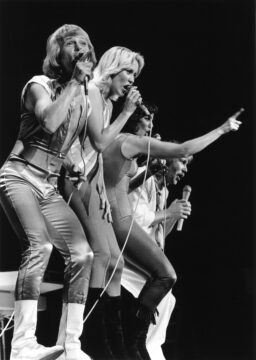

The rapidly escalating military conflict between Israel and Iran represents a clash of ambitions. Iran seeks to become a nuclear power, and Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu longs to be remembered as the Israeli leader who categorically thwarted Iran’s nuclear program, which he views as an existential threat to Israel’s survival. Both dreams are as misguided as they are dangerous. There is probably not a second that goes by without an ABBA song being played somewhere in the world. A remix of “Gimme! Gimme! Gimme! (A Man After Midnight)” is pulsing through a club on a Mediterranean island, a Vietnamese grocery store is piping in “Happy New Year,” a Mexican radio station is playing the Spanish-language version of “Knowing Me, Knowing You.” Live performances, too, continue unabated, and not just in karaoke bars, or in stage productions of “

There is probably not a second that goes by without an ABBA song being played somewhere in the world. A remix of “Gimme! Gimme! Gimme! (A Man After Midnight)” is pulsing through a club on a Mediterranean island, a Vietnamese grocery store is piping in “Happy New Year,” a Mexican radio station is playing the Spanish-language version of “Knowing Me, Knowing You.” Live performances, too, continue unabated, and not just in karaoke bars, or in stage productions of “ T

T Harvard never wanted or expected this.

Harvard never wanted or expected this. For years, researchers and policymakers have been sounding the alarm about the limited opportunities children and teenagers have to play and explore without adults around. For instance, children across much of the Western world are less likely to hold part-time jobs or

For years, researchers and policymakers have been sounding the alarm about the limited opportunities children and teenagers have to play and explore without adults around. For instance, children across much of the Western world are less likely to hold part-time jobs or  W

W To tap into the flow state, your skill level and the challenge of the task you’re working on should be in perfect balance. This is one of the eight principles of flow, first described by the Hungarian scientist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. He coined the term ‘flow’ in 1990 after decades of scientific work about what surgeons, painters, dancers, writers, scientists, martial artists, musicians and other creatives have in common – a curious, all-absorbing state of mind where we feel amazing and are incredibly productive and creative at the same time.

To tap into the flow state, your skill level and the challenge of the task you’re working on should be in perfect balance. This is one of the eight principles of flow, first described by the Hungarian scientist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. He coined the term ‘flow’ in 1990 after decades of scientific work about what surgeons, painters, dancers, writers, scientists, martial artists, musicians and other creatives have in common – a curious, all-absorbing state of mind where we feel amazing and are incredibly productive and creative at the same time. Let’s be frank: It’s a somewhat presumptuous name for a magazine. Adopting it may have been akin to what philosophers refer to as a “speech act,” meant to call into being the very thing referred to. Largely absent from pre–Civil War political rhetoric, which more often spoke of “the union” or “the republic,” the word nation appeared five times in Abraham Lincoln’s 1863 Gettysburg Address. Two years later, when the first issue

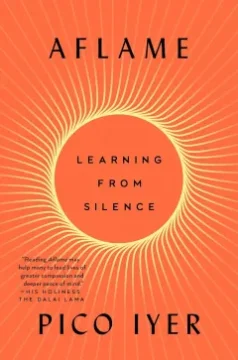

Let’s be frank: It’s a somewhat presumptuous name for a magazine. Adopting it may have been akin to what philosophers refer to as a “speech act,” meant to call into being the very thing referred to. Largely absent from pre–Civil War political rhetoric, which more often spoke of “the union” or “the republic,” the word nation appeared five times in Abraham Lincoln’s 1863 Gettysburg Address. Two years later, when the first issue  The best measure of serenity may be our distance from the self — getting far enough to dim the glare of ego and quiet the din of the mind, with all its ruminations and antagonisms, in order to see the world more clearly, in order to hear more clearly our own inner voice, the voice that only ever speak of love.

The best measure of serenity may be our distance from the self — getting far enough to dim the glare of ego and quiet the din of the mind, with all its ruminations and antagonisms, in order to see the world more clearly, in order to hear more clearly our own inner voice, the voice that only ever speak of love.