Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

Elon Musk Thought He Could Break History. Instead It Broke Him

David Nasaw in The New York Times:

The partnership between the president and the richest man in the world is coming to an end. There is one clear loser in the breakup of this affair, and it is Elon Musk.

The partnership between the president and the richest man in the world is coming to an end. There is one clear loser in the breakup of this affair, and it is Elon Musk.

He fell from grace as effortlessly as he had risen. Like a dime-store Icarus, he took too many chances, never understood the risks and flew too close to the sun. Wrapped in the halo of his social-media superstardom, he was blinded to the reality of his circumstances until it was too late.

Mr. Musk has already inked several lucrative federal contracts and could get far more, but he leaves Washington with his reputation as a genius jack-of-all-trades — a reputation he relied on to boost his company’s stock prices and win investors for his ambitious adventures — severely damaged. Once likened to the Marvel superhero Tony Stark, he is becoming increasingly unpopular. Many formerly proud owners of his Tesla electric cars are trading them in or pasting apologies on their bumpers. Sales have plummeted.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Trump Mother’s Day Cold Open

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Joseph Nye (1937 – 2025) Political Scientist

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

George Lee (1935 – 2025) Ballet Dancer

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sunday Poem

A Call

‘Hold on,’ she said, ‘I’ll just run out and get him.

The weather here’s so good, he took the chance

To do a bit of weeding.’

………………………………… So I saw him

Down on his hands and knees beside the leek rig,

Touching, inspecting, separating one

Stalk from another, gently pulling up

Everything not tapered, frail and leafless,

Pleased to feel each little weed-root break,

But rueful also . . .

…………………………… Then I found myself listening to

The amplified grave ticking of hall clocks

Where the phone lay unattended in a calm

Of mirror glass and sunstruck pendulums . . .

And found myself then thinking: if it were nowadays,

This is how Death would summon Everyman.

Next thing he spoke and I nearly said I loved him.

by Seamus Heaney

from The Spirit Level

Farrar Straus Giroux New York, 1996

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Stricken Leviathans

Tony Wood in Sidecar:

On 5 March, Mexican families searching for missing relatives made a grim discovery at a ranch in Teuchitlán, Jalisco: two hundred pairs of shoes, heaps of clothing and fragments of bone. The place had been raided by the National Guard last September and a handful of arrests made, but at the time the authorities had seemingly missed the horrors that lay just beneath the soil, which were quickly taken as evidence that the ranch had been used as a site for systematic slaughter.

The Teuchitlán case prompted renewed outrage in Mexico, both at the government’s handling of the investigation and at its inability to curb the rising toll of deaths and disappearances that has scarred Mexico since President Felipe Calderón launched his ‘war on drugs’ in 2006. Statistics can convey only a fraction of what this cataclysm has wrought, but they are staggering enough: over 400,000 homicides since 2006, the majority of them related to narco violence, and more than 127,000 people still missing, with many tens of thousands more internally displaced due to the violence. Two decades on, no end is in sight, and despite the dramatic political shifts occasioned by Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s victory in 2018 and that of his successor, Claudia Sheinbaum, in 2024, here at least there has been a monstrous continuity.

The consequences will be working their way through Mexican society for decades to come.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Green Indicative Planning

Cornel Ban and Jacob Hasselbalch in Phenomenal World:

Energy transitions the world over are at an impasse. With the Trump administration’s scrapping of the Inflation Reduction Act and the mobilization of the European Far Right against existing climate legislation, the future of an effective market-based environmentalism that delivers real climate mitigation on time has been thrown into profound doubt. As the climate clock ticks, liberal democracies are being driven toward either a defensive and vague green liberalism or an aggressive and illiberal retrenchment of fossil capitalist growth.

Amid worrying climate forecasts, and unresolved political struggle for the future of the advanced economies, it is now more important than ever to envision a feasible course for the green transition. While some economists on the left have begun to invoke ideas such as “democratic economic planning” or “ecosocialist planning” to describe institutions that might achieve this transition, the planning imperative—determining national and international goals on the size and composition of gross output of various economic sectors, and achieving the levels of public and private spending necessary to induce the desired supply responses—does not demand a revolutionary restructuring of national economies as a prerequisite for emissions reductions.1 Rather, as we have argued recently, existing states can plan the coming energy transition despite the power of private capital—multinational corporations, credit rating agencies, sovereign bond investors, and global institutional investors—constraining them. In fact, planning may be the most direct route to states reclaiming power over private capital for public purposes.

Our suggested approach is more indicative in nature. It is responsive and complementary to political institutions, rather than supplantive of them in the way so many twentieth-century programs for the transition to socialism attempted to be. It is a continuation of the longstanding tradition of indicative planning in post-war societies, largely forgotten during the era of neoliberalism.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Go Short!

Dania Rajendra in Dilettante Army:

American football, like all politics, is war by other means. Quite literally, American college students (men) invented the game in 1869, stressed about having “missed out” on serving in the Civil War. It was part of a decades-long freakout about masculinity associated with, variously, the 1879 economic panic, the closing of the frontier and new adventures in off-shore colonialism, the industrial revolution, labor organizing, Reconstruction and the (re)installation of racist terror, waves of immigration, and women’s agitating for rights, including the right to vote, and, of course, ideas of gender and social equality threaded through left-wing organizing and practice gaining momentum through the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth.

Amidst all that, American football developed primarily on elite college campuses, causing the kind of player injuries—and deaths—the sport is again known for today. After news reports in 1905 detailed 19 casualties and 138 hospitalizations, Progressive Era reformers sought to ban the sport against the wishes of men who attended elite colleges. The next year, President Theodore Roosevelt struck a compromise between the reformers and the men that included changing the rules to allow players to toss— “pass”—the ball in addition to carrying it.

It took a hundred years—an entire century—for the better strategy to become the default. Why did it take so long to change the playbook?

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday, May 9, 2025

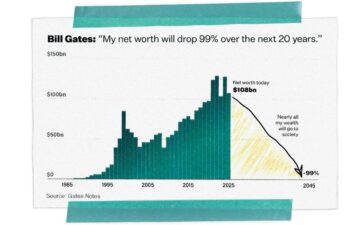

Bill Gates: 20 years to give away virtually all my wealth

Bill Gates at Gates Notes:

One of the best things I read was an 1889 essay by Andrew Carnegie called The Gospel of Wealth. It makes the case that the wealthy have a responsibility to return their resources to society, a radical idea at the time that laid the groundwork for philanthropy as we know it today.

One of the best things I read was an 1889 essay by Andrew Carnegie called The Gospel of Wealth. It makes the case that the wealthy have a responsibility to return their resources to society, a radical idea at the time that laid the groundwork for philanthropy as we know it today.

In the essay’s most famous line, Carnegie argues that “the man who dies thus rich dies disgraced.” I have spent a lot of time thinking about that quote lately. People will say a lot of things about me when I die, but I am determined that “he died rich” will not be one of them. There are too many urgent problems to solve for me to hold onto resources that could be used to help people.

That is why I have decided to give my money back to society much faster than I had originally planned. I will give away virtually all my wealth through the Gates Foundation over the next 20 years to the cause of saving and improving lives around the world. And on December 31, 2045, the foundation will close its doors permanently.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Announcing the Golden Gate Institute for AI

Steve Newman at Second Thoughts:

Do you feel like you’re able to keep up with developments in AI? I don’t. The impossibility is a running joke among insiders.

Do you feel like you’re able to keep up with developments in AI? I don’t. The impossibility is a running joke among insiders.

If you’re following events, you’ll have seen the launch of AI 2027, a detailed scenario of how AI may unfold. As you might guess from the title, the analysis projects the arrival of ASI – artificial superintelligence – in as little as three years. The highly qualified authors include Daniel Kokotajlo, an ex-OpenAI employee who wrote a prescient forecast of AI progress in 2021, and superforecaster Eli Lifland.

Meanwhile, Dwarkesh Patel’s always-excellent podcast just dropped an interview with two equally qualified researchers from Epoch AI, titled “AGI is Still 30 Years Away”.

These are two of the best sources of information available regarding AI timelines, and they’re starkly contradictory. Is transformative AI 3 years away, or 30? We’re left to our own devices to decide what to believe.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

After surviving a crash, Nick becomes a stranger to himself: Diary of a Head Injury

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

“Terrorist”: Two short-short stories

Amitava Kumar at his Substack:

Here’s the first short short-story I have for you about boys.

Here’s the first short short-story I have for you about boys.

When I was working on my book Husband of a Fanatic, and traveling in Kashmir, several people told me about a story by Akhtar Mohiuddin’s entitled “Terrorist.” The story’s popularity might be explained by the fact that it outlines a situation where the loss of innocence is represented not through the expected assault but, instead, by the seductive power of violence. In Mohiuddin’s story, a woman named Farz Ded is walking down a narrow street. From the opposite end of the street, a military patrol approaches her. Farz Ded’s young son starts crying. The patrol’s commander thinks that the kid is scared and he reassures him. Farz Ded says to the officer, “This rogue is not afraid of you. He just sees the soldiers and cries, ‘I want a gun … I want a gun.”‘“

The second short short-story is from this morning.

I watched a news-clip in which a boy is asked by a reporter holding a microphone whether he is ashamed. The boy asks in return why he should be ashamed. The reporter asks, Long live India, yes or no? The boy says, Yes. The reporter now asks, Long live Pakistan, yes or no? The boy says, Yes. And then he adds crucially, with a wisdom far beyond his years, Long live everyone in their own places. You too long live in your place…

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Cat Power

Charlotte Shane at Bookforum:

WHEN THE WRITER MAYUMI INABA meets Mii, the kitten who will become “the center of her life,” the animal is stuck in a school fence, screaming for rescue in the night air: a “little white dot” deposited there “out of malice or mischief” by a culprit long departed. There is no sign of her mother or littermates, no evidence that she is owned or loved or named. She is flea-bitten, only a few days old, exhausted, and of obscure origin. “All I knew,” Inaba writes of the moment she collected this defenseless being into her hands, “was that she must have felt utterly desperate.” Any cat person worth their fur-covered clothes can guess what happens next; Inaba is subsumed in devotion to this creature, with its face “the size of a coin.” Her life will be ruled by Mii until Mii’s own life ends, and that is right and good.

WHEN THE WRITER MAYUMI INABA meets Mii, the kitten who will become “the center of her life,” the animal is stuck in a school fence, screaming for rescue in the night air: a “little white dot” deposited there “out of malice or mischief” by a culprit long departed. There is no sign of her mother or littermates, no evidence that she is owned or loved or named. She is flea-bitten, only a few days old, exhausted, and of obscure origin. “All I knew,” Inaba writes of the moment she collected this defenseless being into her hands, “was that she must have felt utterly desperate.” Any cat person worth their fur-covered clothes can guess what happens next; Inaba is subsumed in devotion to this creature, with its face “the size of a coin.” Her life will be ruled by Mii until Mii’s own life ends, and that is right and good.

Cat people are the only conceivable audience for Mornings Without Mii, an uneventful memoir in which a Japanese woman—married at the beginning of the book, later divorced—loves and lives with a cat who succumbs to old age. Who else would be entertained by meticulous descriptions of Mii sleeping, playing in newspapers, sniffing everything she comes across, lapping up milk?

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Hiroshi Sugimoto On Music And Art

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

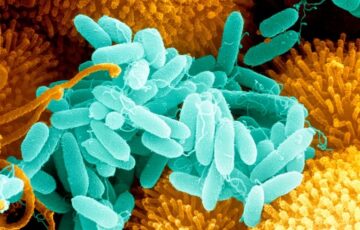

Microbe that infests hospitals can digest medical-grade plastic ― a first

Rachel Fieldhouse in Nature:

A strain of bacterium that often causes infections in hospital can break down plastic, research published this week in Cell Reports reveals1. Researchers in the United Kingdom identified an enzyme, which they called Pap1, in a strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from a wound. They found that the enzyme can break down a plastic that is commonly used in health care because of its biodegradable properties, called polycaprolactone (PCL).

A strain of bacterium that often causes infections in hospital can break down plastic, research published this week in Cell Reports reveals1. Researchers in the United Kingdom identified an enzyme, which they called Pap1, in a strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from a wound. They found that the enzyme can break down a plastic that is commonly used in health care because of its biodegradable properties, called polycaprolactone (PCL).

Until now, the only enzymes shown to break down plastics were found in environmental bacteria, says study co-author Ronan McCarthy, who researches bacteria and bacterial infections at Brunel University in London. He says that finding the same ability in pathogens often present in hospitals could explain why these microbes persist in these environments. “If a pathogen can degrade plastic, then it could compromise plastic-containing medical devices such as sutures, implants, stents or wound dressings, which would obviously negatively impact patient prognosis,” he adds.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

First American Pope Makes History and MAGA Catholics Already Have Issues

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Dianaworld: An Obsession

Nicola Shulman at Literary Review:

‘Always be nice to girls, you never know who they’ll become’ was a common saying among the generation of upper-class Englishwomen born around 1900. Diana Spencer’s life was a spectacular demonstration of its wisdom. It is now almost impossible to conceive what little consequence accrued to a third daughter, born between two prayed-for boys – the elder dead in infancy, the younger living – in a primogeniture-practising family in the middle of the last century. Yet this lowly person became the most famous woman in the world. We can only imagine how her brother felt.

‘Always be nice to girls, you never know who they’ll become’ was a common saying among the generation of upper-class Englishwomen born around 1900. Diana Spencer’s life was a spectacular demonstration of its wisdom. It is now almost impossible to conceive what little consequence accrued to a third daughter, born between two prayed-for boys – the elder dead in infancy, the younger living – in a primogeniture-practising family in the middle of the last century. Yet this lowly person became the most famous woman in the world. We can only imagine how her brother felt.

That gymnastic overturning of childhood expectations lies at the bottom of many of the contradictions and paradoxical behaviours examined in Dianaworld, which analyses what that girl did become. Not just to herself, but to the various tribes and individuals who followed her progress, helped her, obsessed over her, tortured her, fantasised about her, used her, and in one way or another couldn’t leave her alone – a state of affairs she craved and feared in equal measure. Edward White’s categories are extensive. Her relationships with hairdressers, Americans, clothes designers, politicians, gays, newspapermen, staff, family members, superfans, lovers, prostitutes, children (hers and other people’s) are paraded here in an effort to unpeel the lacquer of mythology that accumulated on her persona and made her shine with such appalling brightness.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday Poem

Fall Cleaning

Books read, unread, and never-will-be-read,

jottings, the remains of paid bills, old tax forms,

unopened software, letters years old still to be

answered, manuals, CD’s, Judith’s note saying

Cecily’s ballet class has been canceled 20 years

ago, a picture of my mother, in her 30’s, standing

by Arthur Melrose dressed in a dinner jacket. out-

side the frame of the picture 1-1/2 X 2-1/2, black

and white, fading, live his brothers, and Helen

and Jennie, his sisters – and Jennie’s Model T with

the rumble seat ancient even then and her picking me

up at the train station at Huntington, Long Island,

the clatter of her car louder than the great diesel,

I hungry for sliced cheese and Ritz Crackers.

The morning after. Everything spread about the family

room looking for order, for boxes, for trash cans, for

attention, the chains and palaces of my life. I lie in bed

reading Jorie Graham, “The earth curves more than

I had thought /at first.” I walk along the shore of an ancient

beach. Yesterday sinks just beyond the horizon. I poke

among the seaweed for what is left, cast up, from the

shipwreck of each day, 365 a year, back and back,

“In the beginning, there was…”

by Nils Peterson

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Thursday, May 8, 2025

The Opposite of Déjà Vu Can Happen, And It’s Even More Uncanny

Akira O’Connor & Christopher Moulin at Science Alert:

The opposite of déjà vu is “jamais vu”, when something you know to be familiar feels unreal or novel in some way. In our recent research, which has won an Ig Nobel award for literature, we investigated the mechanism behind the phenomenon.

The opposite of déjà vu is “jamais vu”, when something you know to be familiar feels unreal or novel in some way. In our recent research, which has won an Ig Nobel award for literature, we investigated the mechanism behind the phenomenon.

Jamais vu may involve looking at a familiar face and finding it suddenly unusual or unknown. Musicians have it momentarily – losing their way in a very familiar passage of music. You may have had it going to a familiar place and becoming disorientated or seeing it with “new eyes”.

It’s an experience which is even rarer than déjà vu and perhaps even more unusual and unsettling. When you ask people to describe it in questionnaires about experiences in daily life they give accounts like: “While writing in my exams, I write a word correctly like ‘appetite’ but I keep looking at the word over and over again because I have second thoughts that it might be wrong.”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.