Emma Merchant in Undark Magazine:

The lab buildings of Long Island’s renowned Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory have hosted researchers responsible for some of the most consequential scientific leaps in human genetics and disease. In the last 60 years, eight of the lab’s scientists have earned Nobel Prizes, including for work on how viruses replicate, on chromosome structure, and how edited genes can cause disease.

The lab buildings of Long Island’s renowned Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory have hosted researchers responsible for some of the most consequential scientific leaps in human genetics and disease. In the last 60 years, eight of the lab’s scientists have earned Nobel Prizes, including for work on how viruses replicate, on chromosome structure, and how edited genes can cause disease.

That setting felt auspicious when nearly two-dozen people, most of them researchers, gathered at a conference center about 5 miles from the main campus in December 2023 to lay out the definition for a budding scientific discipline nearly two decades in the making. The work aims to understand human health outcomes by cataloguing the tens of thousands of chemicals and conditions a person is exposed to over the course of their life and determine how those interactions affect their unique biology, a concept referred to as the exposome.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Harvard never wanted or expected this.

Harvard never wanted or expected this. For years, researchers and policymakers have been sounding the alarm about the limited opportunities children and teenagers have to play and explore without adults around. For instance, children across much of the Western world are less likely to hold part-time jobs or

For years, researchers and policymakers have been sounding the alarm about the limited opportunities children and teenagers have to play and explore without adults around. For instance, children across much of the Western world are less likely to hold part-time jobs or  W

W To tap into the flow state, your skill level and the challenge of the task you’re working on should be in perfect balance. This is one of the eight principles of flow, first described by the Hungarian scientist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. He coined the term ‘flow’ in 1990 after decades of scientific work about what surgeons, painters, dancers, writers, scientists, martial artists, musicians and other creatives have in common – a curious, all-absorbing state of mind where we feel amazing and are incredibly productive and creative at the same time.

To tap into the flow state, your skill level and the challenge of the task you’re working on should be in perfect balance. This is one of the eight principles of flow, first described by the Hungarian scientist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. He coined the term ‘flow’ in 1990 after decades of scientific work about what surgeons, painters, dancers, writers, scientists, martial artists, musicians and other creatives have in common – a curious, all-absorbing state of mind where we feel amazing and are incredibly productive and creative at the same time. Let’s be frank: It’s a somewhat presumptuous name for a magazine. Adopting it may have been akin to what philosophers refer to as a “speech act,” meant to call into being the very thing referred to. Largely absent from pre–Civil War political rhetoric, which more often spoke of “the union” or “the republic,” the word nation appeared five times in Abraham Lincoln’s 1863 Gettysburg Address. Two years later, when the first issue

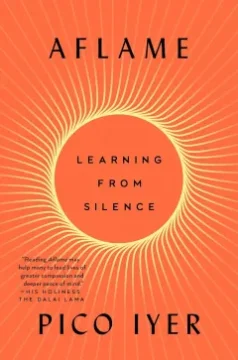

Let’s be frank: It’s a somewhat presumptuous name for a magazine. Adopting it may have been akin to what philosophers refer to as a “speech act,” meant to call into being the very thing referred to. Largely absent from pre–Civil War political rhetoric, which more often spoke of “the union” or “the republic,” the word nation appeared five times in Abraham Lincoln’s 1863 Gettysburg Address. Two years later, when the first issue  The best measure of serenity may be our distance from the self — getting far enough to dim the glare of ego and quiet the din of the mind, with all its ruminations and antagonisms, in order to see the world more clearly, in order to hear more clearly our own inner voice, the voice that only ever speak of love.

The best measure of serenity may be our distance from the self — getting far enough to dim the glare of ego and quiet the din of the mind, with all its ruminations and antagonisms, in order to see the world more clearly, in order to hear more clearly our own inner voice, the voice that only ever speak of love. When Jeanne Calment died at the age of 122, her

When Jeanne Calment died at the age of 122, her  I came to all

I came to all In matters of style

In matters of style The annual Berggruen Prize Essay Competition seeks to stimulate new thinking and innovative concepts while embracing cross-cultural perspectives across fields, disciplines, and geographies. By posing fundamental philosophical questions of significance for both contemporary life and for the future, the competition will serve as a complement to the Berggruen Prize for Philosophy & Culture, which recognizes major lifetime achievements in advancing ideas that have shaped the world.

The annual Berggruen Prize Essay Competition seeks to stimulate new thinking and innovative concepts while embracing cross-cultural perspectives across fields, disciplines, and geographies. By posing fundamental philosophical questions of significance for both contemporary life and for the future, the competition will serve as a complement to the Berggruen Prize for Philosophy & Culture, which recognizes major lifetime achievements in advancing ideas that have shaped the world. At the turn of the 20th century, the renowned mathematician David Hilbert had a grand ambition to bring a more rigorous, mathematical way of thinking into the world of physics. At the time, physicists were still plagued by debates about basic definitions — what is heat? how are molecules structured? — and Hilbert hoped that the formal logic of mathematics could provide guidance.

At the turn of the 20th century, the renowned mathematician David Hilbert had a grand ambition to bring a more rigorous, mathematical way of thinking into the world of physics. At the time, physicists were still plagued by debates about basic definitions — what is heat? how are molecules structured? — and Hilbert hoped that the formal logic of mathematics could provide guidance. As I’ve learned more about what the future of AI might look like, I’ve come to better appreciate the real dangers that this technology poses. There were always two ways in which AI could be misused. The first is happening now: AI technologies like deep fakes are already widely in circulation. My Instagram feed is full of videos of things I am sure never happened like catastrophic building collapses or MAGA celebrities explaining how wrong they were. It is, however, nearly impossible to verify whether or not they are real. This kind of manipulation is going to further undermine trust in institutions and exacerbate polarization. There are plenty of other malign uses to which sophisticated AI can be put, like raiding your bank account and launching devastating cyber-attacks on basic infrastructure. Bad actors are everywhere.

As I’ve learned more about what the future of AI might look like, I’ve come to better appreciate the real dangers that this technology poses. There were always two ways in which AI could be misused. The first is happening now: AI technologies like deep fakes are already widely in circulation. My Instagram feed is full of videos of things I am sure never happened like catastrophic building collapses or MAGA celebrities explaining how wrong they were. It is, however, nearly impossible to verify whether or not they are real. This kind of manipulation is going to further undermine trust in institutions and exacerbate polarization. There are plenty of other malign uses to which sophisticated AI can be put, like raiding your bank account and launching devastating cyber-attacks on basic infrastructure. Bad actors are everywhere. IF THE CHOICE were up to Zimbabwe, it would pursue a path independent of South Africa, the powerful and domineering neighbor across the Limpopo River to its south. Yet, because of fate, history, and the accidents of geography, the most significant forces that shaped modern Zimbabwe and its predecessor, Southern Rhodesia, came from across the frontier. In the 1820s, a fugitive general named Mzilikazi, fleeing the Zulu warrior-king Shaka, crossed the border from present-day KwaZulu-Natal (on the southeast Indian Ocean coast), where he would found the Ndebele state. In 1890 came the colonial encroachment by British–South African empire man Cecil John Rhodes, after whom the country was named. Zimbabwe and South Africa share in Rhodes a common ancestor; in Ndebele a language with a close connection to Zulu (the most spoken language in South Africa); and the common visual vocabulary sometimes called Ndebele art.

IF THE CHOICE were up to Zimbabwe, it would pursue a path independent of South Africa, the powerful and domineering neighbor across the Limpopo River to its south. Yet, because of fate, history, and the accidents of geography, the most significant forces that shaped modern Zimbabwe and its predecessor, Southern Rhodesia, came from across the frontier. In the 1820s, a fugitive general named Mzilikazi, fleeing the Zulu warrior-king Shaka, crossed the border from present-day KwaZulu-Natal (on the southeast Indian Ocean coast), where he would found the Ndebele state. In 1890 came the colonial encroachment by British–South African empire man Cecil John Rhodes, after whom the country was named. Zimbabwe and South Africa share in Rhodes a common ancestor; in Ndebele a language with a close connection to Zulu (the most spoken language in South Africa); and the common visual vocabulary sometimes called Ndebele art. The discovery began, as many breakthroughs do, with an observation that didn’t quite make sense. In 1948, two French researchers, Paul Mandel and Pierre Métais, published a little-noticed paper in a scientific journal. Working in a laboratory in Strasbourg, they had been cataloguing the chemical contents of blood plasma—that river of life teeming with proteins, sugars, waste, nutrients, and cellular debris. Amid this familiar inventory, they’d spotted an unexpected presence: fragments of DNA drifting freely.

The discovery began, as many breakthroughs do, with an observation that didn’t quite make sense. In 1948, two French researchers, Paul Mandel and Pierre Métais, published a little-noticed paper in a scientific journal. Working in a laboratory in Strasbourg, they had been cataloguing the chemical contents of blood plasma—that river of life teeming with proteins, sugars, waste, nutrients, and cellular debris. Amid this familiar inventory, they’d spotted an unexpected presence: fragments of DNA drifting freely.