Nicholas Barber at the BBC:

If we’re talking about culture that makes people happy, we have to start with the works of PG Wodehouse. There are two reasons why. One reason is that making people happy was Wodehouse’s overriding ambition. The other reason is that he was better at it than any other writer in history.

If we’re talking about culture that makes people happy, we have to start with the works of PG Wodehouse. There are two reasons why. One reason is that making people happy was Wodehouse’s overriding ambition. The other reason is that he was better at it than any other writer in history.

Some authors may want to expose the world’s injustices, or elevate us with their psychological insights. Wodehouse, in his words, preferred to spread “sweetness and light”. Just look at those titles: Nothing Serious, Laughing Gas, Joy in the Morning. With every sparkling joke, every well-meaning and innocent character, every farcical tussle with angry swans and pet Pekingese, every utopian description of a stroll around the grounds of a pal’s stately home or a flutter on the choir boys’ hundred yards handicap at a summer village fete, he wanted to whisk us far away from our worries. Writing about being a humourist in his autobiography Over Seventy, Wodehouse quoted two people in the Talmud who had earnt their place in Heaven: “We are merrymakers. When we see a person who is downhearted, we cheer him up.”

More here.

What does it mean to be great? Whom shall we call great? How can we become great? Is greatness the same as goodness? These questions involve fundamental ethical assumptions, concepts and concerns. Like many who addressed such issues in the past, we often use virtues — courage, generosity, forbearance, etc. — in order to explain what greatness means, reflecting a common notion that greatness requires moral integrity. Virtues describe our ambitions and aspirations, as individuals and as communities. How we give credit for moral achievements is presumably also culturally conditioned, just as the way we relate to our accomplishments in general reflects social and historical context. Studies on the Dunning-Kruger effect suggest that while North Americans regularly overestimate their abilities, in Japan the opposite appears to be the case. Other variables too are sometimes debated. The self-citation rate among male scientists is often reported to be higher than among their female peers, which might reflect a higher estimation of their achievements. Differences are also believed to be generational and related to educational practices around appreciation and rewards. Recent public debates have shed light on the psychological and emotional costs of self-optimizing and the social and political dynamics of virtue-signaling. Likewise, who our role models should be and how they are selected often reveals the diverging views of greatness in a society. Even a brief survey of these and similar discussions suggests that the philosophical problem of greatness can be of significant interest to contemporary readers.

What does it mean to be great? Whom shall we call great? How can we become great? Is greatness the same as goodness? These questions involve fundamental ethical assumptions, concepts and concerns. Like many who addressed such issues in the past, we often use virtues — courage, generosity, forbearance, etc. — in order to explain what greatness means, reflecting a common notion that greatness requires moral integrity. Virtues describe our ambitions and aspirations, as individuals and as communities. How we give credit for moral achievements is presumably also culturally conditioned, just as the way we relate to our accomplishments in general reflects social and historical context. Studies on the Dunning-Kruger effect suggest that while North Americans regularly overestimate their abilities, in Japan the opposite appears to be the case. Other variables too are sometimes debated. The self-citation rate among male scientists is often reported to be higher than among their female peers, which might reflect a higher estimation of their achievements. Differences are also believed to be generational and related to educational practices around appreciation and rewards. Recent public debates have shed light on the psychological and emotional costs of self-optimizing and the social and political dynamics of virtue-signaling. Likewise, who our role models should be and how they are selected often reveals the diverging views of greatness in a society. Even a brief survey of these and similar discussions suggests that the philosophical problem of greatness can be of significant interest to contemporary readers. The cultured and literate Amedeo Modigliani (1884-1920) was passionately interested in and emotionally involved with Italian and French poetry of the past as well as with the work of his friends, Anna Ahkmatova, Max Jacob and Blaise Cendrars. On the 100th anniversary of his tragic death in 1920 we can see how the poets who fascinated him portrayed the pain of sex and love, the exaltation of art, the effect of narcotics on creativity and the need to suffer extreme experience. They encouraged his compulsion to live dangerously, and taught him to see the artist as victim, outcast and superman. They provided intellectual justification for the deliberate derangement of his senses and glorified his devotion to art. He didn’t just read poets. He lived according to their principles as if they were imprinted on his body as well as in his mind. These powerful poets both inspired his work and—as he was drawn to disaster and followed their maniacal descent–helped to destroy him.

The cultured and literate Amedeo Modigliani (1884-1920) was passionately interested in and emotionally involved with Italian and French poetry of the past as well as with the work of his friends, Anna Ahkmatova, Max Jacob and Blaise Cendrars. On the 100th anniversary of his tragic death in 1920 we can see how the poets who fascinated him portrayed the pain of sex and love, the exaltation of art, the effect of narcotics on creativity and the need to suffer extreme experience. They encouraged his compulsion to live dangerously, and taught him to see the artist as victim, outcast and superman. They provided intellectual justification for the deliberate derangement of his senses and glorified his devotion to art. He didn’t just read poets. He lived according to their principles as if they were imprinted on his body as well as in his mind. These powerful poets both inspired his work and—as he was drawn to disaster and followed their maniacal descent–helped to destroy him. Like most big-idea books, this one begins by absurdly overstating the novelty of its argument. The author promises to reveal “a radical idea” that has been “erased from the annals of world history”. It is, even, “a new view of humankind”. Some measure of bathos is presumably intended when we learn that this radical new view is that “most people, deep down, are pretty decent”. But there appears to be no authorial shame over the laughably bogus claim that this idea has been “erased” from history, presumably by a dark centuries-long conspiracy of secretive misanthropes, to some bafflingly obscure end. Not yet erased from the annals of history, for example, is the 18th-century philosopher

Like most big-idea books, this one begins by absurdly overstating the novelty of its argument. The author promises to reveal “a radical idea” that has been “erased from the annals of world history”. It is, even, “a new view of humankind”. Some measure of bathos is presumably intended when we learn that this radical new view is that “most people, deep down, are pretty decent”. But there appears to be no authorial shame over the laughably bogus claim that this idea has been “erased” from history, presumably by a dark centuries-long conspiracy of secretive misanthropes, to some bafflingly obscure end. Not yet erased from the annals of history, for example, is the 18th-century philosopher  Thousands of academics and major scientific organizations worldwide will stop work on 10 June as part of a global stand against anti-Black racism in science. More than 4,000 scientists as well as societies, universities and publishers, will join a call to “Strike for Black Lives,” halting their usual work activities to learn about systemic racism in the research community and to craft ways to address inequalities. The event is being planned by two ad hoc groups of scientists using hashtags such as

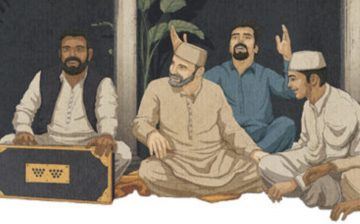

Thousands of academics and major scientific organizations worldwide will stop work on 10 June as part of a global stand against anti-Black racism in science. More than 4,000 scientists as well as societies, universities and publishers, will join a call to “Strike for Black Lives,” halting their usual work activities to learn about systemic racism in the research community and to craft ways to address inequalities. The event is being planned by two ad hoc groups of scientists using hashtags such as  After barreling through the relentlessly flat, verdant Punjabi hinterland in a rented Toyota, stopping briefly for naan, kebabs, and petrol, we hit town at three, four in the morning, and at three, four in the morning, music wafts through the still, sticky summer air. Millions gather each year for ten days in the hilly medieval town of Pakpattan, in Pakistan, to commemorate the death anniversary of the twelfth-century saint Baba Farid, celebrating the reunion of man and his maker with qawwali—call it Muslim soul. When Doc, a pal and Pakpattan regular, urged me to join him on the pilgrimage the night before—it’s Baba’s 776th death anniversary, he informs me—I decided to accompany him. I can’t refuse Doc: I’ve got his back; he’s got mine. And who knows? Perhaps Baba will bless me as well. But you have to believe to be blessed.

After barreling through the relentlessly flat, verdant Punjabi hinterland in a rented Toyota, stopping briefly for naan, kebabs, and petrol, we hit town at three, four in the morning, and at three, four in the morning, music wafts through the still, sticky summer air. Millions gather each year for ten days in the hilly medieval town of Pakpattan, in Pakistan, to commemorate the death anniversary of the twelfth-century saint Baba Farid, celebrating the reunion of man and his maker with qawwali—call it Muslim soul. When Doc, a pal and Pakpattan regular, urged me to join him on the pilgrimage the night before—it’s Baba’s 776th death anniversary, he informs me—I decided to accompany him. I can’t refuse Doc: I’ve got his back; he’s got mine. And who knows? Perhaps Baba will bless me as well. But you have to believe to be blessed. When protests erupted in the US in response to the killing of George Floyd on May 25, the anger over police brutality was also fuelled by a sense of simmering injustice over the impact of coronavirus. Not only have black people died from the disease in disproportionately high numbers: there are early signs they will bear the brunt of the economic fallout too.

When protests erupted in the US in response to the killing of George Floyd on May 25, the anger over police brutality was also fuelled by a sense of simmering injustice over the impact of coronavirus. Not only have black people died from the disease in disproportionately high numbers: there are early signs they will bear the brunt of the economic fallout too. A podcast only hits the century mark once! And for Mindscape, this is it. There have been holiday messages and bonus episodes and the like. But this is the 100th officially-numbered episode. To celebrate, I decided to treat myself to a solo episode in which I reflect, somewhat non-systematically, on the age-old question of the meaning of life. I end up spending a lot (most?) of the time talking about the meaning of “life,” i.e. what it means to be a living organism in a naturalistic universe. But then I go on to muse about the construction of human meaning in a world where values are not imposed on us or objectively grounded in physical facts.

A podcast only hits the century mark once! And for Mindscape, this is it. There have been holiday messages and bonus episodes and the like. But this is the 100th officially-numbered episode. To celebrate, I decided to treat myself to a solo episode in which I reflect, somewhat non-systematically, on the age-old question of the meaning of life. I end up spending a lot (most?) of the time talking about the meaning of “life,” i.e. what it means to be a living organism in a naturalistic universe. But then I go on to muse about the construction of human meaning in a world where values are not imposed on us or objectively grounded in physical facts. Less than two weeks after Floyd’s killing, the American death toll from the novel coronavirus has surpassed 100,000. Rates of infection,

Less than two weeks after Floyd’s killing, the American death toll from the novel coronavirus has surpassed 100,000. Rates of infection,  We moved forward with the idea of assembling a canon, aware of the chutzpah, based on a few understandings. One is our belief that even when canon formation is not taking place explicitly in a closed gathering, certain ideas and texts become implicitlycanonical through other means such as compelling presentation, citation, and education. Communities and consensuses can create canon by bringing powerful ideas to life and to market, and by privileging some ideas and texts over others. For example, Yosef H. Yerushalmi’s Zakhor is required reading in dozens of college and graduate school courses in Jewish Studies; it is among the most commonly cited texts in Jewish Studies lectures in both academic and lay settings. No one person decided that the book is important, but the book has emerged over time as a canonical piece of Jewish Studies scholarship with relevance for the larger Jewish community. In engaging actively and directly in canon formation, in naming what we were doing an act of “canonization,” and in inviting commentary from our colleagues we hoped to call attention to the implicit canonization that was already happening and to open a conversation about it.

We moved forward with the idea of assembling a canon, aware of the chutzpah, based on a few understandings. One is our belief that even when canon formation is not taking place explicitly in a closed gathering, certain ideas and texts become implicitlycanonical through other means such as compelling presentation, citation, and education. Communities and consensuses can create canon by bringing powerful ideas to life and to market, and by privileging some ideas and texts over others. For example, Yosef H. Yerushalmi’s Zakhor is required reading in dozens of college and graduate school courses in Jewish Studies; it is among the most commonly cited texts in Jewish Studies lectures in both academic and lay settings. No one person decided that the book is important, but the book has emerged over time as a canonical piece of Jewish Studies scholarship with relevance for the larger Jewish community. In engaging actively and directly in canon formation, in naming what we were doing an act of “canonization,” and in inviting commentary from our colleagues we hoped to call attention to the implicit canonization that was already happening and to open a conversation about it. 100,000 square metres of fabric was used to wrap the Reichstag in 1995. Christo and Jeanne-Claude said at the time that the project was born out of his ‘acute interest’ as a political refugee in the relationship between East and West: ‘Here they meet in the most dramatic way.’ The event received wide press coverage, like all their projects, but was also the subject of a personal documentary about Christo and Anani. Standing beside the wrapped Reichstag, leaning against the remains of the Berlin Wall, Anani, by then a famous actor, is anguished: ‘I never had Hristo’s energy. He left with a pencil in his pocket and made it. I never dared.’

100,000 square metres of fabric was used to wrap the Reichstag in 1995. Christo and Jeanne-Claude said at the time that the project was born out of his ‘acute interest’ as a political refugee in the relationship between East and West: ‘Here they meet in the most dramatic way.’ The event received wide press coverage, like all their projects, but was also the subject of a personal documentary about Christo and Anani. Standing beside the wrapped Reichstag, leaning against the remains of the Berlin Wall, Anani, by then a famous actor, is anguished: ‘I never had Hristo’s energy. He left with a pencil in his pocket and made it. I never dared.’ There is an unholy invocation that rises from some Americans in times of racial distress. It is an exclamation from the voices of the status quo, the clarion call of conservative thinking: What would Martin Luther King do? It is as unauthentic and uninspiring as it is ambiguous – and that is the point. Reducing Dr. King’s understanding of racial and social issues to a warped perspective of the “I Have A Dream” speech is propagandist and ahistorical, but it has worked.

There is an unholy invocation that rises from some Americans in times of racial distress. It is an exclamation from the voices of the status quo, the clarion call of conservative thinking: What would Martin Luther King do? It is as unauthentic and uninspiring as it is ambiguous – and that is the point. Reducing Dr. King’s understanding of racial and social issues to a warped perspective of the “I Have A Dream” speech is propagandist and ahistorical, but it has worked. The first thing

The first thing  The call to “defund the police” has

The call to “defund the police” has  For vonny leclerc

For vonny leclerc