Category: Recommended Reading

Bonnie Pointer (1950 – 2020)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2SDjCnVt7og

Vicki Wood (1919 – 2020)

How Architecture Could Help Us Adapt to the Pandemic

Kim Tingley in The New York Times:

The last class Joel Sanders taught in person at the Yale School of Architecture, on Feb. 17, took place in the modern wing of the Yale University Art Gallery, a structure of brick, concrete, glass and steel that was designed by Louis Kahn. It is widely hailed as a masterpiece. One long wall, facing Chapel Street, is windowless; around the corner, a short wall is all windows. The contradiction between opacity and transparency illustrates a fundamental tension museums face, which happened to be the topic of Sanders’s lecture that day: How can a building safeguard precious objects and also display them? How do you move masses of people through finite spaces so that nothing — and no one — is harmed?

The last class Joel Sanders taught in person at the Yale School of Architecture, on Feb. 17, took place in the modern wing of the Yale University Art Gallery, a structure of brick, concrete, glass and steel that was designed by Louis Kahn. It is widely hailed as a masterpiece. One long wall, facing Chapel Street, is windowless; around the corner, a short wall is all windows. The contradiction between opacity and transparency illustrates a fundamental tension museums face, which happened to be the topic of Sanders’s lecture that day: How can a building safeguard precious objects and also display them? How do you move masses of people through finite spaces so that nothing — and no one — is harmed?

All semester, Sanders, who is a professor at Yale and also runs Joel Sanders Architect, a studio located in Manhattan, had been asking his students to consider a 21st-century goal for museums: to make facilities that were often built decades, if not centuries, ago more inclusive. They had conducted workshops with the gallery’s employees to learn how the iconic building could better meet the needs of what Sanders calls “noncompliant bodies.” By this he means people whose age, gender, race, religion or physical or cognitive abilities often put them at odds with the built environment, which is typically designed for people who embody dominant cultural norms. In Western architecture, Sanders points out, “normal” has been explicitly defined — by the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius, for instance, whose concepts inspired Leonardo da Vinci’s “Vitruvian Man,” and, in Kahn’s time, by Le Corbusier’s “Modulor Man” — as a youngish, tallish white male.

When the coronavirus crisis prompted Yale to move classes online, Sanders’s first thought was: “How do you make the content of your class seem relevant during a global pandemic? Why should we be talking about museums when we have more urgent issues to fry?” Off campus, built environments and the ways people moved in them began to change immediately in desperate, ad hoc ways. Grocery stores erected plexiglass shields in front of registers and put stickers or taped lines on the floor to create six-foot spacing between customers; as a result, fewer shoppers fit safely inside, and lines snaked out the door. People became hyperaware of themselves in relation to others and the surfaces they might have to touch. Suddenly, Sanders realized, everyone had become a “noncompliant body.” And places deemed essential were wrestling with how near to let them get to one another. The virus wasn’t simply a health crisis; it was also a design problem.

More here.

Bread, Cement, Cactus – indignation and injustice

Ashish Ghadiali in The Guardian:

Annie Zaidi was already a writer of renown in Mumbai when, in 2019, she submitted a 3,000-word essay to the Nine Dots Prize, an international competition lavishly sponsored by investment banker Peter Kadas, and won $100,000 as well as a book deal. Bread, Cement, Cactus, her haunting evocation of belonging and dislocation in contemporary India, is the fruit of that endeavour, delivering Zaidi on to an international platform for the first time in her decade-long career. The brief was to say something new about “home” – a concept that Zaidi quickly establishes has always evaded her. “I never lived,” she tells us, “in the city of my birth … (Allahabad, now Prayagraj, in Uttar Pradesh). Leaving us with her parents [in Lucknow] while she went back to university, my mother quit a bad marriage.” Later, she found a job and moved to a remote industrial township in Rajasthan where “the need for bread, and milk for the children, overrode her unease at being so far from everything familiar”.

Annie Zaidi was already a writer of renown in Mumbai when, in 2019, she submitted a 3,000-word essay to the Nine Dots Prize, an international competition lavishly sponsored by investment banker Peter Kadas, and won $100,000 as well as a book deal. Bread, Cement, Cactus, her haunting evocation of belonging and dislocation in contemporary India, is the fruit of that endeavour, delivering Zaidi on to an international platform for the first time in her decade-long career. The brief was to say something new about “home” – a concept that Zaidi quickly establishes has always evaded her. “I never lived,” she tells us, “in the city of my birth … (Allahabad, now Prayagraj, in Uttar Pradesh). Leaving us with her parents [in Lucknow] while she went back to university, my mother quit a bad marriage.” Later, she found a job and moved to a remote industrial township in Rajasthan where “the need for bread, and milk for the children, overrode her unease at being so far from everything familiar”.

Each chapter is a standalone essay, as Zaidi looks back to the successive settings of an itinerant past, successfully dovetailing personal reflection with political analysis so that, in each location, intimate memories work as jumping-off points for research and investigation into the macro-trends that are shaping contemporary India. In that Rajasthani township, JK Puram, for example, Zaidi’s recollection of youthful discontent plays into a reckoning with the horror of tribal dispossession as stories from her childhood of “Bhil tribesmen … who could relieve kids of their valuables” are slowly recast.

…In the end, the architecture of the book attempts to lead us towards a counter-resolution that will establish home instead in the paradise of personal experience – in “the morning mist” for example – but this is never as convincing as the lasting sense of indignation and injustice that Zaidi evokes. “What belongs to whom?” she asks. “Who pays the costs of what is taken and cannot be returned?” These are questions perhaps more powerful than the answers Zaidi can provide, but it’s through questions such as these that she points towards the deeper mysteries of our human condition.

More here.

Sunday Poem

Floating

We are in the good Target, picking out bathing suits

for a last-minute invitation to the beach. My daughter

is nine. Mom, she whispers, can I get the, you know

(holding up two fingers), the two-piece?

And I say sure because her trust in me

is a swirled marble sinking slowly in an aqua pool.

Already she questions my answers,

looks sideways when I tell what I know.

Last month I bought her a sweatshirt

with The Future Is Female printed in simple black letters.

And today, what? The florescent rainbow bikini?

I can’t tell her yet what the world will expect

of her body—complicit, my own hands wanting

a little longer, that familiar weight, heavy bloom

of her scented head—salt, sleep, sun.

by Karen Harryman

from Narrative Magazine

Saturday, June 13, 2020

The Post-Pandemic Social Contract

Dani Rodrik and Stefanie Stantcheva in Project Syndicate:

COVID-19 has exacerbated deep fault lines in the global economy, starkly exposing the divisions and inequalities of our current world. It has also multiplied and amplified the voices of those calling for far-reaching reforms. When even the Davos set is issuing calls for a “global reset of capitalism,” you know that changes are afoot.

There are some common threads running through the newly proposed policy agendas: To prepare the workforce for new technologies, governments must enhance education and training programs, and integrate them better with labor-market requirements. Social protection and social insurance must be improved, especially for workers in the gig economy and in non-standard work arrangements.

More broadly, the decline in workers’ bargaining power in recent decades points to the need for new forms of social dialogue and cooperation between employers and employees. Better-designed progressive taxation must be introduced to address widening income inequality. Anti-monopoly policies must be reinvigorated to ensure greater competition, particularly where social media platforms and new technologies are concerned. Climate change must be tackled head-on. And governments must play a bigger role in fostering new digital and green technologies.

Taken together, these reforms would substantially change the way our economies operate. But they do not fundamentally alter the narrative about how market economies should work; nor do they represent a radical departure for economic policy. Most critically, they elide the central challenge we must address: reorganizing production.

More here.

Commoning the Company

Mathew Lawrence, Adrienne Buller, Joseph Baines & Sandy Hager over at Common Wealth:

Mathew Lawrence, Adrienne Buller, Joseph Baines & Sandy Hager over at Common Wealth:

A devastating public health crisis, Covid-19 has also triggered a profound crisis of the company: from vast multinational corporations to the small firms that are the lifeblood of local economies. The unprecedented economic fallout from the virus has exposed the inefficiencies and injustices embedded in the company’s operation – limitations that stretch back decades. Our response to this crisis cannot ignore these limitations when we emerge from the period of economic hibernation. Instead, it must reimagine the company so that it is democratic, resilient, and sustainable by design – and rebuild a new economy centred on meeting the needs of society and the environment.

Since the 1970s, the company has transformed from an institution focused on production – even if still one laced through with hierarchy and injustices – into an engine of increasing wealth extraction and growing financialisation, funnelling cash to shareholders and executive management in the form of dividends, share buybacks and share-based pay awards. This has been driven by key shifts in the legal, managerial, and ownership structures of the corporation, with an increasing share of corporate earnings redirected to investors and management over workers or re-investment. Shareholding has concentrated and corporate debt has soared, with UK listed company debt reaching record levels by 2018; mergers and acquisitions have created dominant oligopolies in key sectors; managerial power has grown; and labour has been subject to a relentless squeeze on wages, autonomy, and security in order to boost short-term profit.

More here.

Why making economic predictions now is useless

Branko Milanovic over at his website, Global Inequality:

Branko Milanovic over at his website, Global Inequality:

Economists are often in particular demand because they claim they can tell the shape of future demand and supply, unemployment and growth. To do that they resort to models that through behavioral equations and identities, show the future evolution of key variables and pretend to predict how long the depression will last and how quick and strong the recovery will be.

My argument is that such models are useless under today’s conditions. There are several reasons for that.

All economic models, by definition, take the economy as a self-contained system which is exposed to economic shocks, whether in form of more or less relaxed monetary policy, higher or lower taxes, higher or lower minimum wage etc. They cannot by their very nature take into account extra-economic discrete shocks. Such shocks are simply not predictable. One cannot tell today whether China might invade Hong Kong, or whether Trump might ban all imports from China, or whether the race riots in the US can continue for months, or similar riots break out elsewhere in the world (Latin America, Africa, Indonesia) or even if the US may not end this year with a military government in charge.

All of these social and political shocks that I have listed are due to, or have been exacerbated, by the pandemic. There is little doubt that the “most important relationship” (to quote Henry Kissinger), the one between China and the United States, has significantly deteriorated because of the pandemic. Some in the United States see the pandemic as intentionally engineered by China to weaken the US economy and its president.

More here.

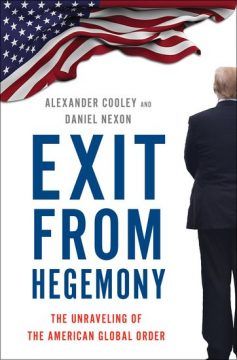

Who Killed American Global Power?

Erik D’Amato reviews Alex Cooley and Dan Nexon’s new book, Exit from Hegemony: The Unraveling of the American Global Order in The LA Review of Books:

Erik D’Amato reviews Alex Cooley and Dan Nexon’s new book, Exit from Hegemony: The Unraveling of the American Global Order in The LA Review of Books:

WHEN I SLIPPED into home isolation in late March, I started catching up on promising-looking television — especially a series called Occupied, about a creeping Russian invasion of Norway set in the near future in which the United States fails to stand up for its longtime NATO ally.

The day I started binging, the tiny former Yugoslav republic of North Macedonia became the 30th member of NATO, and it made me wonder if American citizens would really think that an attack there was — in the old principle of the alliance — an attack on them as well. Probably not

And so there’s an appropriate cover on the new study Exit from Hegemony: The Unraveling of the American Global Order by the political scientists Alexander Cooley and Daniel Nexon. We see Donald Trump turning his back under a buffeted American flag.

Cooley and Nexon spend a fair bit of time discussing past hegemonic orders, including important but now wonderfully obscure particulars like the Second Schmalkaldic War of 1552–1555, and defining various related theories and idioms, starting with “hegemony,” which is meant as a technical term without sinister connotation. There are also helpful reminders that the phrase “international order” itself is problematic, as the order it describes is not static but constantly shifting, and that both internationalism and nationalism, the latter expressed as national self-determination, have historically both been seen as liberal concepts.

The golden age

John Quiggin in Aeon:

John Quiggin in Aeon:

I first became an economist in the early 1970s, at a time when revolutionary change still seemed like an imminent possibility and when utopian ideas were everywhere, exemplified by the Situationist slogan of 1968: ‘Be realistic. Demand the impossible.’ Preferring to think in terms of the possible I was much influenced by an essay called ‘Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren,’ written in 1930 by John Maynard Keynes, the great economist whose ideas still dominated economic policymaking at the time.

Like the rest of Keynes’s work, the essay ceased to be discussed very much during the decades of free-market liberalism that led up to the global financial crisis of 2007 and the ensuing depression, through which most of the developed world is still struggling. And, also like the rest of Keynes’s work, this essay has enjoyed a revival of interest in recent years, promoted most notably by the Keynes biographer Robert Skidelsky and his son Edward.

The Skidelskys have revived Keynes’s case for leisure, in the sense of time free to use as we please, as opposed to idleness. As they point out, their argument draws on a tradition that goes back to the ancients. But Keynes offered something quite new: the idea that leisure could be an option for all, not merely for an aristocratic minority.

More here.

Why Are the Police Like This?

Alex Gourevitch in Jacobin:

The police are out of control. They murder unarmed, poor, disproportionately nonwhite people with near total impunity. They provoke protests, antagonize protesters, arrest journalists, and violate civil liberties. They torture detainees and run black sites for interrogations. Their unions protect them from accountability, demand special legal protection, and undermine the political authority of any mayor, governor, or public figure that even mildly criticizes them. They refuse to collect and share national data on how often, when, and against whom they mete out violence while on the beat. They reject the minimal requirements of a democratic society to know how they operate.

The police have become an independent, organized body that relates to the public more or less the way an occupying army relates to the native population. How did they get like this?

Excellent work has shown how the police preserve racial hierarchies, in part by using force disproportionately against minorities, especially black people. The police were central to W. E. B. Du Bois’s theory of how the ruling class used racial ideology to divide workers who shared economic interests. As recent protests have awakened the public to this “social control” function of the police, they have also opened up the space to ask a basic question: why are there police in the first place? What interests do they serve, and why have they become so militarized?

More here.

Susan Sontag and John Berger

Miss Aluminium

Fiona Struges at The Guardian:

On her first night in Los Angeles, the model-turned-author Susanna Moore slept in a broom cupboard. She was 21, and had been flown in by a producer to appear in the 1967 Dean Martin spy comedy, The Ambushers. Prior to this she had been working as a fashion model and was helping to put her husband, Bill, through college in Chicago. With barely a cent to her name, she arrived to find the hotel was not expecting her. The desk clerk took pity and sent her to the fourth floor where there was a tiny closet crammed with bleach, toilet brushes and mops. There Moore bedded down on a small rusty cot, the smell of ammonia in her nostrils. Despite this inauspicious start, she was “neither worried nor afraid”, and soon resolved to leave her husband and make LA her home.

On her first night in Los Angeles, the model-turned-author Susanna Moore slept in a broom cupboard. She was 21, and had been flown in by a producer to appear in the 1967 Dean Martin spy comedy, The Ambushers. Prior to this she had been working as a fashion model and was helping to put her husband, Bill, through college in Chicago. With barely a cent to her name, she arrived to find the hotel was not expecting her. The desk clerk took pity and sent her to the fourth floor where there was a tiny closet crammed with bleach, toilet brushes and mops. There Moore bedded down on a small rusty cot, the smell of ammonia in her nostrils. Despite this inauspicious start, she was “neither worried nor afraid”, and soon resolved to leave her husband and make LA her home.

more here.

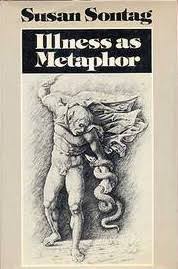

Illness As Fantasy

Rachel Fraser at The Point:

Metaphors of illness come in two varieties. We may give an illness a name that is not its own—“cancer is an invasion.” Or we may use the names of illnesses to talk about something else—“Stalinism is a cancer.” In the first case, Sontag says, “the disease itself becomes a metaphor”; in the second, the disease’s “horror is imposed on other things.” Sontag takes both to distort the patient’s experience of illness by overlaying it with meanings it does not deserve. But the two deserve separate treatments. “Stalinism is a cancer” exploits illness; it uses sickness to cast light on something else. It presupposes that cancer is more straightforward, more readily comprehensible than Stalinism—otherwise, why try to understand the latter in terms of the former? It obscures cancer precisely by presenting it as readily comprehensible. “Cancer is an invasion” is something else entirely, something far more likely to be used by someone seeking to make sense of their own sickness. Audre Lorde reaches for the image repeatedly in her memoir. “I am not only a casualty,” she writes in The Cancer Journals. “I have been to war, and still am. … I refuse to be reduced in my own eyes … from warrior to mere victim.”

Metaphors of illness come in two varieties. We may give an illness a name that is not its own—“cancer is an invasion.” Or we may use the names of illnesses to talk about something else—“Stalinism is a cancer.” In the first case, Sontag says, “the disease itself becomes a metaphor”; in the second, the disease’s “horror is imposed on other things.” Sontag takes both to distort the patient’s experience of illness by overlaying it with meanings it does not deserve. But the two deserve separate treatments. “Stalinism is a cancer” exploits illness; it uses sickness to cast light on something else. It presupposes that cancer is more straightforward, more readily comprehensible than Stalinism—otherwise, why try to understand the latter in terms of the former? It obscures cancer precisely by presenting it as readily comprehensible. “Cancer is an invasion” is something else entirely, something far more likely to be used by someone seeking to make sense of their own sickness. Audre Lorde reaches for the image repeatedly in her memoir. “I am not only a casualty,” she writes in The Cancer Journals. “I have been to war, and still am. … I refuse to be reduced in my own eyes … from warrior to mere victim.”

more here.

One Hundred Years Ago, a Lynch Mob Killed Three Men in Minnesota

Francine Ouenuma in Smithsonian:

Over the years, the horror of June 15, 1920, when three black men were lynched by a white mob in Duluth, faded away behind a “collective amnesia,” says author Michael Fedo. Faded away, at least, in the memories of Duluth’s white community. In the 1970s, when Fedo began researching what would become The Lynchings in Duluth, the first detailed accounting of the night’s events, he met resistance from witnesses who were still alive. “All of them said, gee, why are you dredging this up again? All of them except the African American community in Duluth. It was part of their oral history, and all of those families knew of this event,” Fedo recalls. On that late spring night, 100 years ago, a crowd estimated at 5,000 people smashed their way into the Duluth police station and seized six African American men who had been arrested in connection with the alleged crime of raping a white teenager. After a mock trial in which three of them—Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson and Isaac McGhie—were “convicted,” a crowd of men, women and children cheered as they were beaten and lynched, one by one. Photos of the macabre aftermath were later sold as postcards, while the national press reported on the incident with dismay.

Over the years, the horror of June 15, 1920, when three black men were lynched by a white mob in Duluth, faded away behind a “collective amnesia,” says author Michael Fedo. Faded away, at least, in the memories of Duluth’s white community. In the 1970s, when Fedo began researching what would become The Lynchings in Duluth, the first detailed accounting of the night’s events, he met resistance from witnesses who were still alive. “All of them said, gee, why are you dredging this up again? All of them except the African American community in Duluth. It was part of their oral history, and all of those families knew of this event,” Fedo recalls. On that late spring night, 100 years ago, a crowd estimated at 5,000 people smashed their way into the Duluth police station and seized six African American men who had been arrested in connection with the alleged crime of raping a white teenager. After a mock trial in which three of them—Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson and Isaac McGhie—were “convicted,” a crowd of men, women and children cheered as they were beaten and lynched, one by one. Photos of the macabre aftermath were later sold as postcards, while the national press reported on the incident with dismay.

…In the final moments before the lynching, some tried to reason with the crowd. According to Fedo, two judges arrived to plead the case for the law to take its course, but to no avail. A local Catholic priest, William Powers, climbed the post himself. “In the name of God and the church I represent, I ask you to stop,” he entreated the crowd, according to a report in the National Advocate. His exhortation fell on deaf ears amid the din of rallying cries, which by then included false reports of Tusken’s death. Duluth’s white population readily accepted the rape allegation, and were eager to condemn the African American prisoners. “It wasn’t as if [Powers] was dealing with a small group of people who were a minority in a society,” says William D. Green, professor of history at Augsburg Universityand a member of the Minnesota Historical Society’s Emeritus Council. “The mob of Duluth was made up of all classes, mothers taking their kids.”

The three victims had themselves barely reached adulthood. According to Fedo, pleas of innocence from McGhie—the first to be lynched—did nothing to dissuade the mob. Witnesses later recalled the second man, Jackson, coolly throwing a pair of dice from his pocket on the ground with the words “I won’t need these any more in this world.”

More here.

Melville’s Whale Was a Warning We Failed to Heed

Carl Safina in The New York Times:

In 1841, while aboard the whaler Acushnet, Herman Melville met William Chase among another ship’s complement. William lent Melville a book by his father, Owen Chase: “Narrative of the Most Extraordinary and Distressing Shipwreck of the Whale-Ship Essex.” Melville had read Jeremiah Reynolds’s violent account of a sperm whale “white as wool,” named — for his haunt near Mocha Island, off the coast of Chile — Mocha Dick. It’s unknown what led Melville to tweak Mocha to “Moby.” Good thing he did, and that Starbuck was the name he gave his first mate rather than his captain. Otherwise the novel would follow Starbuck’s obsession with a Mocha. Owen Chase gave Melville his climax: As Essex’s boats were harpooning female sperm whales, a huge male, around 85 feet, rushed and holed the 88-foot ship, twice. No whale had ever sunk a ship. “The reading of this wondrous story upon the landless sea, and so close to the very latitude of the shipwreck had a surprising effect upon me,” Melville later recalled.

In 1841, while aboard the whaler Acushnet, Herman Melville met William Chase among another ship’s complement. William lent Melville a book by his father, Owen Chase: “Narrative of the Most Extraordinary and Distressing Shipwreck of the Whale-Ship Essex.” Melville had read Jeremiah Reynolds’s violent account of a sperm whale “white as wool,” named — for his haunt near Mocha Island, off the coast of Chile — Mocha Dick. It’s unknown what led Melville to tweak Mocha to “Moby.” Good thing he did, and that Starbuck was the name he gave his first mate rather than his captain. Otherwise the novel would follow Starbuck’s obsession with a Mocha. Owen Chase gave Melville his climax: As Essex’s boats were harpooning female sperm whales, a huge male, around 85 feet, rushed and holed the 88-foot ship, twice. No whale had ever sunk a ship. “The reading of this wondrous story upon the landless sea, and so close to the very latitude of the shipwreck had a surprising effect upon me,” Melville later recalled.

He initially planned a book about whales and whaling. Reynolds helped supply Melville with a more Stygian idea, by exhorting his men to attack Mocha Dick as “though he were Beelzebub himself!” — a demon rather than a whale. Yet Moby Dick is neither whale nor demon, but a white prop contrasting with the demonic Captain Ahab, the tormented tormentor, the malignant, abused abuser of authority and of men. Ahab’s bias is personal and color-based. A white whale becomes a blank pincushion for Ahab’s thrusting mania as Melville shades pages with his madness. Yet — and this was absolutely astonishing for its time — Moby Dick becomes the ultimate asserter of reason. In self-defense the whale delivers justice. And never dies.

…By the 1840s, having ventured half the world away from America, Melville cast a frigatebird-like perspective on the American character’s deepest congenital malignancy, then called Negrophobia. In the early 19th century, sperm whale hunting was never far from slave trading. Thomas Beale’s 1839 “The Natural History of the Sperm Whale” included this telling dedication to the British shipowner Thomas Sturge: “Your character may be estimated by the incessant efforts you have made to liberate the Negro from the condition of the slave.” On docks and decks humans of varied skin shades and breathing one another’s sweat in close company tended whale-boiling caldrons and looked one another in the eye. Light-skinned men could feel trapped and dark men could taste freedom, surviving, sometimes drowning, together. Melville’s ever-philosophical narrator, Ishmael, asks: “Who ain’t a slave? Tell me that.”

More here.

Saturday Poem

Thesaurus

It could be the name of a prehistoric beast

that roamed the Paleozoic earth, rising up

on its hind legs to show off its large vocabulary,

or some lover in a myth who is metamorphosed into a book.

It means treasury, but it is just a place

where words congregate with their relatives,

a big park where hundreds of family reunions

are always being held,

house, home, abode, dwelling, lodgings, and digs,

all sharing the same picnic basket and thermos;

hairy, hirsute, woolly, furry, fleecy, and shaggy

all running a sack race or throwing horseshoes,

inert, static, motionless, fixed and immobile

standing and kneeling in rows for a group photograph.

Here father is next to sire and brother close

to sibling, separated only by fine shades of meaning.

And every group has its odd cousin, the one

who traveled the farthest to be here:

astereognosis, polydipsia, or some eleven

syllable, unpronounceable substitute for the word tool.

Even their own relatives have to squint at their name tags.

I can see my own copy up on a high shelf.

I rarely open it, because I know there is no

such thing as a synonym and because I get nervous

around people who always assemble with their own kind,

forming clubs and nailing signs to closed front doors

while others huddle alone in the dark streets.

I would rather see words out on their own, away

from their families and the warehouse of Roget,

wandering the world where they sometimes fall

in love with a completely different word.

Surely, you have seen pairs of them standing forever

next to each other on the same line inside a poem,

a small chapel where weddings like these,

between perfect strangers, can take place.

by Billy Collins

from The Art of Drowning

University of Pittsburg Press, 1995

Friday, June 12, 2020

Maths rules: Where the dialectic takes us

Jonathan Egid in the Times Literary Supplement:

A grisly cultic murder is an unusual starting point for a work of philosophy, but this opening is typical of Justin E. H. Smith’s new book. It is one of many vivid impressionistic sketches – what Smith calls “instructive ornamentations” – employed to lend support to his dialectical thesis: that rationality is inextricably linked, in society as in the individual, to its irrational opposite. Rationality or reason (the terms are used interchangeably) never exists alone. It is always and everywhere mixed up with its ineliminable “dark side”, liable to erupt violently wherever faith in reason is strongest. Irrationality explores the manifestations of this enlightenment-into-darkness paradigm as it unfolds in history and contemporary politics.

A grisly cultic murder is an unusual starting point for a work of philosophy, but this opening is typical of Justin E. H. Smith’s new book. It is one of many vivid impressionistic sketches – what Smith calls “instructive ornamentations” – employed to lend support to his dialectical thesis: that rationality is inextricably linked, in society as in the individual, to its irrational opposite. Rationality or reason (the terms are used interchangeably) never exists alone. It is always and everywhere mixed up with its ineliminable “dark side”, liable to erupt violently wherever faith in reason is strongest. Irrationality explores the manifestations of this enlightenment-into-darkness paradigm as it unfolds in history and contemporary politics.

According to Smith, the story of any movement with a commitment to rationality, from the Pythagoreans to the Jacobins to LessWrong and Silicon Valley, is the story of a “commitment to an ideal, the discovery within the movement of an ineradicable strain of something antithetical to that ideal, to, finally, descent into that opposite thing”. The unfolding of history always displays the same inexorable logic of an “exaltation of reason, and a desire to eradicate its opposite; the inevitable endurance of irrationality in human life … and, finally, the descent into irrational self-immolation of the very currents of thought and of social organization that had set themselves up as bulwarks against irrationality”. We begin by worshipping ratios, we end up murdering mathematicians.

More here.

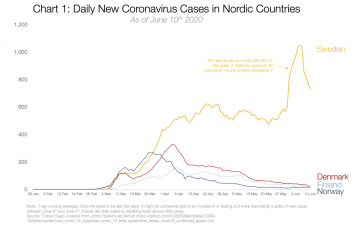

Tomas Pueyo: Should We Aim for Herd Immunity Like Sweden?

Tomas Pueyo in Medium:

Sweden has famously followed a different coronavirus strategy than most of the rest of the Developed world: Let the virus run loose, curb it enough to make sure it doesn’t overwhelm the healthcare system like in Hubei, Italy or Spain, but don’t try to eliminate it. They think stopping it completely is impossible. The natural consequence is that most citizens get infected, and that eventually slows down the epidemic. That’s why, in short, people call that strategy “Herd Immunity”.

Sweden has famously followed a different coronavirus strategy than most of the rest of the Developed world: Let the virus run loose, curb it enough to make sure it doesn’t overwhelm the healthcare system like in Hubei, Italy or Spain, but don’t try to eliminate it. They think stopping it completely is impossible. The natural consequence is that most citizens get infected, and that eventually slows down the epidemic. That’s why, in short, people call that strategy “Herd Immunity”.

The other strategy is the Hammer and the Dance: Aggressively attack the coronavirus by locking down the economy. Once curbed, jump into the Dance by replacing the aggressive lockdown with cheap and intelligent measures to control the virus.

Some countries and states, such as the Netherlands and the UK, or US states like Texas and Georgia, have implemented measures in between the two strategies. So which strategy is best?

Today, we’re going to use a lot of data and charts to answer these questions…

More here.