Richard Wolffe in The Guardian:

Writing from a Birmingham jail, Martin Luther King Jr famously told his anxious fellow clergymen that his non-violent protests would force those in power to negotiate for racial justice. “The time is always ripe to do right,” he wrote. On an early summer evening, two generations later, Donald Trump walked out of the White House, where he’d been hiding in a bunker. Military police had just fired teargas and flash grenades at peaceful protesters to clear his path, so that he could wave a bible in front of a boarded church. For Trump, the time is always ripe to throw kerosene on his own dumpster fire. In the week since George Floyd was killed by Minneapolis police officers, Trump has watched and tweeted helplessly as the nation he pretends to lead has reached its breaking point. After decades of supposedly legal police beatings and murders, the protests have swept America’s cities more quickly than even coronavirus. This is no coincidence of timing. In other crises, in other eras, there have been presidents who understood their most basic duty: to calm the violence and protect the people. In this crisis, however, we have a president who built his entire political career as a gold-painted tower to incite violence.

Writing from a Birmingham jail, Martin Luther King Jr famously told his anxious fellow clergymen that his non-violent protests would force those in power to negotiate for racial justice. “The time is always ripe to do right,” he wrote. On an early summer evening, two generations later, Donald Trump walked out of the White House, where he’d been hiding in a bunker. Military police had just fired teargas and flash grenades at peaceful protesters to clear his path, so that he could wave a bible in front of a boarded church. For Trump, the time is always ripe to throw kerosene on his own dumpster fire. In the week since George Floyd was killed by Minneapolis police officers, Trump has watched and tweeted helplessly as the nation he pretends to lead has reached its breaking point. After decades of supposedly legal police beatings and murders, the protests have swept America’s cities more quickly than even coronavirus. This is no coincidence of timing. In other crises, in other eras, there have been presidents who understood their most basic duty: to calm the violence and protect the people. In this crisis, however, we have a president who built his entire political career as a gold-painted tower to incite violence.

We were told, by Trump’s supporters four years ago, that we should have taken him seriously but not literally. As it happened, it was entirely appropriate to take him literally, as a serious threat to the rule of law. During his 2016 campaign, he encouraged his supporters to assault protesters. “Knock the crap out of them, would you? Seriously, OK,” he said on the day of the Iowa caucuses. “I promise you I will pay for the legal fees.” Later in Las Vegas, he said the security guards were too gentle with another protester. “I’d like to punch him in the face,” he said. Sure enough, a protester was sucker-punched on his way out of a rally the following month. No wonder Trump was sued for incitement to riot by three protesters who were assaulted as they left one of his rallies in Kentucky. The case ultimately failed, but only after a judge ruled that Trump recklessly incited violence against an African-American woman by a crowd that included known members of hate groups.

So when he stood, as president, and told a crowd of police officers to be violent with arrested citizens, it wasn’t some weird joke or misstatement, no matter what his aides claimed afterwards. “When you see these thugs being thrown into the back of a paddy wagon, you just see ’em thrown in, rough, I said, ‘Please don’t be too nice.’

More here.

But musically, Fetch astonishes, the work of an artist absolutely confident in the experiment she’s conducting, her objective aligning happily with the listener’s pleasure. This is a true rarity, the artistic advancement that offers joy or surprise or comfort. (I thought of Mitchell’s The Hissing of Summer Lawns or Björk’s Vespertine or David Bowie’s Station to Station.) The album’s tactics—heavy beats, cut-and-paste vocal play—might frustrate some who prefer Apple’s earlier work, waltzy and cutting.

But musically, Fetch astonishes, the work of an artist absolutely confident in the experiment she’s conducting, her objective aligning happily with the listener’s pleasure. This is a true rarity, the artistic advancement that offers joy or surprise or comfort. (I thought of Mitchell’s The Hissing of Summer Lawns or Björk’s Vespertine or David Bowie’s Station to Station.) The album’s tactics—heavy beats, cut-and-paste vocal play—might frustrate some who prefer Apple’s earlier work, waltzy and cutting.

The year 1918 was an extraordinary historical moment. As the Great War roared to an end after four long years of blood and horror, it appeared briefly that the future of the world lay wide open. The old order was overthrown. States were collapsing. Monarchs, the sons of dynasties that had ruled eastern and central Europe for centuries, abdicated and fled. Noisy, violent crowds of hungry civilians and grim, weary soldiers flooded grey city streets, demanding peace and a better life. In the countryside, peasants chased away the lords who had ruled over them and seized their land. Mad, bad and dangerous revolutionaries pushing radical ideals and preaching utopia saw that their hour had struck. The German theologian Ernst Troeltsch aptly named this time, when no one had a firm grip on power and anything appeared possible, ‘the dreamland of the armistice period’. These excellent books by Jonathan Schneer and Robert Gerwarth both show just how much was at stake and capture the breathless excitement and mortal fear that the upheaval generated.

The year 1918 was an extraordinary historical moment. As the Great War roared to an end after four long years of blood and horror, it appeared briefly that the future of the world lay wide open. The old order was overthrown. States were collapsing. Monarchs, the sons of dynasties that had ruled eastern and central Europe for centuries, abdicated and fled. Noisy, violent crowds of hungry civilians and grim, weary soldiers flooded grey city streets, demanding peace and a better life. In the countryside, peasants chased away the lords who had ruled over them and seized their land. Mad, bad and dangerous revolutionaries pushing radical ideals and preaching utopia saw that their hour had struck. The German theologian Ernst Troeltsch aptly named this time, when no one had a firm grip on power and anything appeared possible, ‘the dreamland of the armistice period’. These excellent books by Jonathan Schneer and Robert Gerwarth both show just how much was at stake and capture the breathless excitement and mortal fear that the upheaval generated.

Neuroscientist

Neuroscientist  In our current political climate, it’s sad but not surprising that a U.S. senator would accuse China’s “brightest minds” of studying in America only to return home “to compete for our jobs, to take our business, and ultimately to steal our property.”

In our current political climate, it’s sad but not surprising that a U.S. senator would accuse China’s “brightest minds” of studying in America only to return home “to compete for our jobs, to take our business, and ultimately to steal our property.” Few things are more unexpected than a genuinely inspirational memoir by a freshman member of Congress. If you’re looking for the perfect antidote to the perpetual tweetstorm of insanity and hatred from Donald Trump, try this beautiful new book from the

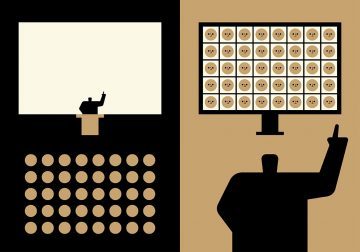

Few things are more unexpected than a genuinely inspirational memoir by a freshman member of Congress. If you’re looking for the perfect antidote to the perpetual tweetstorm of insanity and hatred from Donald Trump, try this beautiful new book from the  Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Adam Fortais had never attended a virtual conference. Now he’s sold on them — and doesn’t want to go back to conventional, in-person gatherings. That’s because of his experience of helping to instigate some virtual sessions for the March meeting of the American Physical Society (APS), after the organization

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Adam Fortais had never attended a virtual conference. Now he’s sold on them — and doesn’t want to go back to conventional, in-person gatherings. That’s because of his experience of helping to instigate some virtual sessions for the March meeting of the American Physical Society (APS), after the organization

There are some problems for which it’s very hard to find the answer, but very easy to check the answer if someone gives it to you. At least, we think there are such problems; whether or not they really exist is the famous

There are some problems for which it’s very hard to find the answer, but very easy to check the answer if someone gives it to you. At least, we think there are such problems; whether or not they really exist is the famous  One of the least expected aspects of 2020 has been the fact that epidemiological models have become both front-page news and a political football. Public health officials have consulted with epidemiological modelers for decades as they’ve attempted to handle diseases ranging from HIV to the seasonal flu. Before 2020, it had been rare for the role these models play to be recognized outside of this small circle of health policymakers.

One of the least expected aspects of 2020 has been the fact that epidemiological models have become both front-page news and a political football. Public health officials have consulted with epidemiological modelers for decades as they’ve attempted to handle diseases ranging from HIV to the seasonal flu. Before 2020, it had been rare for the role these models play to be recognized outside of this small circle of health policymakers. Published shortly after his death in 1633,

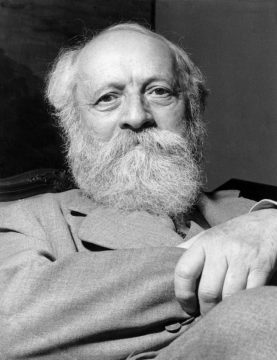

Published shortly after his death in 1633,  “I am unfortunately a complicated and difficult subject.” With these words of Martin Buber, Paul Mendes-Flohr lays down the challenge for his meticulous biography of the distinguished Jewish scholar, humanist, and author of I and Thou. “Complicated,” to be sure, and “difficult,” certainly; that goes with the territory of Buber’s at times maze-like philosophical explorations and heavily Germanic articulation. And one may add to these challenges the fact that—to quote this biographer—Buber was a “contested figure who evoked passionate, conflicting opinions about his person and his thought.” Yet these obstacles are by no means insurmountable, thanks to Mendes-Flohr’s philosophical acumen and gift for succinct expression. Indeed, in his capable hands Buber’s life makes for an engrossing, instructive tale, and an exemplary contribution to Yale’s “Jewish Lives Series.”

“I am unfortunately a complicated and difficult subject.” With these words of Martin Buber, Paul Mendes-Flohr lays down the challenge for his meticulous biography of the distinguished Jewish scholar, humanist, and author of I and Thou. “Complicated,” to be sure, and “difficult,” certainly; that goes with the territory of Buber’s at times maze-like philosophical explorations and heavily Germanic articulation. And one may add to these challenges the fact that—to quote this biographer—Buber was a “contested figure who evoked passionate, conflicting opinions about his person and his thought.” Yet these obstacles are by no means insurmountable, thanks to Mendes-Flohr’s philosophical acumen and gift for succinct expression. Indeed, in his capable hands Buber’s life makes for an engrossing, instructive tale, and an exemplary contribution to Yale’s “Jewish Lives Series.” As universities face major changes, their financial outlook is becoming dire. Revenues are plummeting as students (particularly international ones) remain home or rethink future plans, and endowment funds implode as stock markets drop.

As universities face major changes, their financial outlook is becoming dire. Revenues are plummeting as students (particularly international ones) remain home or rethink future plans, and endowment funds implode as stock markets drop. Writing from a Birmingham jail, Martin Luther King Jr famously told his anxious fellow clergymen that his non-violent protests would force those in power to negotiate for racial justice. “The time is always ripe to do right,” he wrote. On an early summer evening, two generations later,

Writing from a Birmingham jail, Martin Luther King Jr famously told his anxious fellow clergymen that his non-violent protests would force those in power to negotiate for racial justice. “The time is always ripe to do right,” he wrote. On an early summer evening, two generations later,  Epidemiological studies are now revealing that the number of individuals who carry and can pass on the infection, yet remain completely asymptomatic, is larger than originally thought. Scientists believe these people have contributed to the spread of the virus in care homes, and they are central in the debate regarding face mask policies, as health officials attempt to avoid new waves of infections while societies reopen.

Epidemiological studies are now revealing that the number of individuals who carry and can pass on the infection, yet remain completely asymptomatic, is larger than originally thought. Scientists believe these people have contributed to the spread of the virus in care homes, and they are central in the debate regarding face mask policies, as health officials attempt to avoid new waves of infections while societies reopen.