Jeremy Hadfield at his own website:

Having “been reduced to the perplexity of realizing that he did not know… he will go on and discover,” Plato writes of the boy who “feels the difficulty he is in” after attempting to solve Socrates’ riddles. Socrates argues that “by causing him to doubt and giving him the torpedo’s shock” of his own ignorance, “he will push on in the search gladly, as lacking knowledge; whereas then he would have been only too ready to suppose he was right.” Encountering contradictions and complexity beyond his comprehension plunged the boy into aporia — an impasse, a quandary one cannot resolve, a state of puzzlement, a doubting and bewilderment, a being-at-a-loss. Aporia is the dazzling of the mind by the intricacy of existence. While this state seems empty, the paucity of knowledge in aporia is fertile. Specifically, aporia created by literature offers the following routes of learning: it fosters epistemic humility by revealing our uncertainty, broadens our possibilities by expanding our imaginative horizons, and promotes existential authenticity.

Having “been reduced to the perplexity of realizing that he did not know… he will go on and discover,” Plato writes of the boy who “feels the difficulty he is in” after attempting to solve Socrates’ riddles. Socrates argues that “by causing him to doubt and giving him the torpedo’s shock” of his own ignorance, “he will push on in the search gladly, as lacking knowledge; whereas then he would have been only too ready to suppose he was right.” Encountering contradictions and complexity beyond his comprehension plunged the boy into aporia — an impasse, a quandary one cannot resolve, a state of puzzlement, a doubting and bewilderment, a being-at-a-loss. Aporia is the dazzling of the mind by the intricacy of existence. While this state seems empty, the paucity of knowledge in aporia is fertile. Specifically, aporia created by literature offers the following routes of learning: it fosters epistemic humility by revealing our uncertainty, broadens our possibilities by expanding our imaginative horizons, and promotes existential authenticity.

This paper focuses on aporetic literature, a genre of fiction that is usually long-form, complex, and narrative or poetic. Fiction itself is characterized by the way it “invites imaginings.” What distinguishes aporetic literature is a specific “mode of persuasion” distinct from the realist mode of persuasion.

More here.

Pretentiously Opaque would perhaps have made a good alternative title for The Meaninglessness of Meaning, a slim volume collecting some of the LRB’s best writing on “the Theory Wars”, ranging from Brigid Brophy’s review of Colin MacCabe’s James Joyce and the Revolution of the Word (1979) to Adam Shatz’s essay-portrait of Claude Lévi-Strauss (2011), and touching, via essays on various gurus, on most of the key theoretical points in between: Pierre Bourdieu on Jean-Paul Sartre; Richard Rorty on Foucault; Michael Wood on Roland Barthes; Frank Kermode on Paul de Man; Judith Butler on Jacques Derrida; and Lorna Sage on Toril Moi, among others. Pretentious opacity is not, of course, the sort of thing you tend to find in the LRB – as Adam Shatz notes in an elegant introduction, “you’ll never see a piece of ‘pure’ theory in the LRB”, because the paper is committed to “the kind of lucid exposition of ideas that theorists have rejected in favour of a more Baroque, circuitous, self-consciously rarefied style”. The Meaninglessness of Meaning is therefore a partial (and inevitably lopsided) record of how theory fared once it ventured past the campus gates and found itself wandering the streets of the metropolis. More or less useless, I would imagine, to anyone who doesn’t already know something about theory, it nonetheless provokes some interesting reflections on the world that theory made – which is our world, whether we like it or not.

Pretentiously Opaque would perhaps have made a good alternative title for The Meaninglessness of Meaning, a slim volume collecting some of the LRB’s best writing on “the Theory Wars”, ranging from Brigid Brophy’s review of Colin MacCabe’s James Joyce and the Revolution of the Word (1979) to Adam Shatz’s essay-portrait of Claude Lévi-Strauss (2011), and touching, via essays on various gurus, on most of the key theoretical points in between: Pierre Bourdieu on Jean-Paul Sartre; Richard Rorty on Foucault; Michael Wood on Roland Barthes; Frank Kermode on Paul de Man; Judith Butler on Jacques Derrida; and Lorna Sage on Toril Moi, among others. Pretentious opacity is not, of course, the sort of thing you tend to find in the LRB – as Adam Shatz notes in an elegant introduction, “you’ll never see a piece of ‘pure’ theory in the LRB”, because the paper is committed to “the kind of lucid exposition of ideas that theorists have rejected in favour of a more Baroque, circuitous, self-consciously rarefied style”. The Meaninglessness of Meaning is therefore a partial (and inevitably lopsided) record of how theory fared once it ventured past the campus gates and found itself wandering the streets of the metropolis. More or less useless, I would imagine, to anyone who doesn’t already know something about theory, it nonetheless provokes some interesting reflections on the world that theory made – which is our world, whether we like it or not. W

W During the coronavirus pandemic, millions of people are staying home in part to protect the most vulnerable members of their communities from COVID-19. When they do venture out, many don masks, which do less to protect them than to shield any strangers with whom they might inadvertently come into contact. Perhaps the time is ripe to consider the provocative thesis of Dutch historian Rutger Bregman’s new book, “Humankind: A Hopeful History.” His “radical idea”? That “most people, deep down, are pretty decent.” For far too long, Bregman argues, the opposite has been assumed to be true: “There is a persistent myth that by their very nature humans are selfish, aggressive and quick to panic.” Many of our institutions reflect the view of humanity articulated by 17th-century English philosopher Thomas Hobbes, who believed that without a strong ruler, human beings would revert to “a condition of war of all against all.” For his part, Bregman is more aligned with the work of Enlightenment thinker Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who regarded civilization itself as the corrupting force, introducing war, crime, and other horrors that didn’t exist when Homo sapiens lived in a “state of nature.”

During the coronavirus pandemic, millions of people are staying home in part to protect the most vulnerable members of their communities from COVID-19. When they do venture out, many don masks, which do less to protect them than to shield any strangers with whom they might inadvertently come into contact. Perhaps the time is ripe to consider the provocative thesis of Dutch historian Rutger Bregman’s new book, “Humankind: A Hopeful History.” His “radical idea”? That “most people, deep down, are pretty decent.” For far too long, Bregman argues, the opposite has been assumed to be true: “There is a persistent myth that by their very nature humans are selfish, aggressive and quick to panic.” Many of our institutions reflect the view of humanity articulated by 17th-century English philosopher Thomas Hobbes, who believed that without a strong ruler, human beings would revert to “a condition of war of all against all.” For his part, Bregman is more aligned with the work of Enlightenment thinker Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who regarded civilization itself as the corrupting force, introducing war, crime, and other horrors that didn’t exist when Homo sapiens lived in a “state of nature.” Roughly half of Earth’s ice-free land remains without significant human influence, according to a study from a team of international researchers led by the National Geographic Society and the University of California, Davis. The study, published in the journal Global Change Biology, compared four recent global maps of the conversion of natural lands to anthropogenic land uses to reach its conclusions. The more impacted half of Earth’s lands includes cities, croplands, and places intensively ranched or mined. “The encouraging takeaway from this study is that if we act quickly and decisively, there is a slim window in which we can still conserve roughly half of Earth’s land in a relatively intact state,” said lead author Jason Riggio, a postdoctoral scholar at the UC Davis Museum of Wildlife and Fish Biology.

Roughly half of Earth’s ice-free land remains without significant human influence, according to a study from a team of international researchers led by the National Geographic Society and the University of California, Davis. The study, published in the journal Global Change Biology, compared four recent global maps of the conversion of natural lands to anthropogenic land uses to reach its conclusions. The more impacted half of Earth’s lands includes cities, croplands, and places intensively ranched or mined. “The encouraging takeaway from this study is that if we act quickly and decisively, there is a slim window in which we can still conserve roughly half of Earth’s land in a relatively intact state,” said lead author Jason Riggio, a postdoctoral scholar at the UC Davis Museum of Wildlife and Fish Biology. You may have noticed that there are a lot of writers writing a lot about the coronavirus. As every day passes, I want to read these pieces less and less. I don’t care about the subtleties of your daily experience under lockdown, Sensitive Writer Person. I don’t care about your analysis of how everything is going to change or about how everything is actually not really going to change, Journalist. I am indifferent as to your recommendations, Pundit. I give not a crap about your brilliant reading of Camus in light of COVID-19, Essayist. I’m in a boycott, a deep boycott. I will read nothing about coronavirus until 2030; this is my current and most solemn pledge.

You may have noticed that there are a lot of writers writing a lot about the coronavirus. As every day passes, I want to read these pieces less and less. I don’t care about the subtleties of your daily experience under lockdown, Sensitive Writer Person. I don’t care about your analysis of how everything is going to change or about how everything is actually not really going to change, Journalist. I am indifferent as to your recommendations, Pundit. I give not a crap about your brilliant reading of Camus in light of COVID-19, Essayist. I’m in a boycott, a deep boycott. I will read nothing about coronavirus until 2030; this is my current and most solemn pledge. When representation theory emerged in the late 19th century, many mathematicians questioned its worth. In 1897, the English mathematician William Burnside wrote that he doubted that this unorthodox perspective would yield any new results at all.

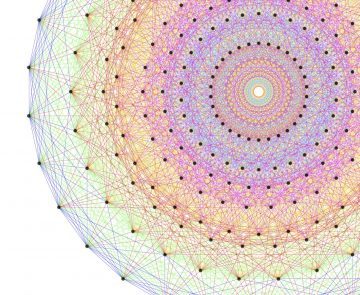

When representation theory emerged in the late 19th century, many mathematicians questioned its worth. In 1897, the English mathematician William Burnside wrote that he doubted that this unorthodox perspective would yield any new results at all. Tear gas rounds describe a graceful arc as they drop down out of the blue sky, trailing feathery tails of smoke like streamers. The shells hit the road with a ping, and sparks fly as they skip gaily along the asphalt. As they roll to a stop, the shells hiss like an angry snake, dense smoke pouring out of the top of the small aluminum canister, and soon the street is enveloped in clouds.

Tear gas rounds describe a graceful arc as they drop down out of the blue sky, trailing feathery tails of smoke like streamers. The shells hit the road with a ping, and sparks fly as they skip gaily along the asphalt. As they roll to a stop, the shells hiss like an angry snake, dense smoke pouring out of the top of the small aluminum canister, and soon the street is enveloped in clouds. I first discovered

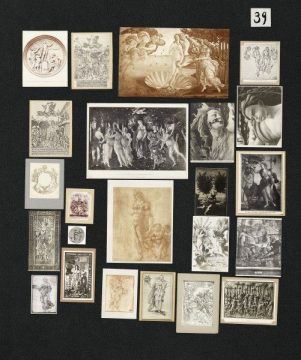

I first discovered  It was only in the second volume of Warburg’s Gesammelte Schriften (Collected Writings), published in 2000, that the glass negatives created in 1929 were used to publish fragmentary pictorial evidence of the “Bilderatlas Mnemosyne.” Editors Martin Warnke and Claudia Brink produced black-and-white images from the negatives, printing them at a reduced size that tended to obscure their details. They also left off additional commentary, given the lack of extant captioning by Warburg himself. This publication was in no small part encouraged by the resurgence of interest in the works of Walter Benjamin (1892–1940), whose theories of media and history had come to seem prescient, particularly in the Anglophone world, with the 1969 Illuminations, edited and introduced by Hannah Arendt and subsequently popularized by John Berger in his 1972 TV series and book, Ways of Seeing. (While Warburg was only peripherally aware of Benjamin during his lifetime, Benjamin sent Warburg a copy of his thesis on Baroque Trauerspiel, or tragic drama, which cited Warburg.) Like Benjamin, who often engaged in leaps of thought and argument by way of metaphorical image rather than logical deduction, Warburg was concerned with Zwischenräume, the spaces in between, as well as something he termed Denkraum, or room for thought.

It was only in the second volume of Warburg’s Gesammelte Schriften (Collected Writings), published in 2000, that the glass negatives created in 1929 were used to publish fragmentary pictorial evidence of the “Bilderatlas Mnemosyne.” Editors Martin Warnke and Claudia Brink produced black-and-white images from the negatives, printing them at a reduced size that tended to obscure their details. They also left off additional commentary, given the lack of extant captioning by Warburg himself. This publication was in no small part encouraged by the resurgence of interest in the works of Walter Benjamin (1892–1940), whose theories of media and history had come to seem prescient, particularly in the Anglophone world, with the 1969 Illuminations, edited and introduced by Hannah Arendt and subsequently popularized by John Berger in his 1972 TV series and book, Ways of Seeing. (While Warburg was only peripherally aware of Benjamin during his lifetime, Benjamin sent Warburg a copy of his thesis on Baroque Trauerspiel, or tragic drama, which cited Warburg.) Like Benjamin, who often engaged in leaps of thought and argument by way of metaphorical image rather than logical deduction, Warburg was concerned with Zwischenräume, the spaces in between, as well as something he termed Denkraum, or room for thought. The style of To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life is more restrained and controlled than these earlier works, but full of well-noticed contrasting details that combine to create an effect that Guibert—apropos of The Compassion Protocol, his last work before his suicide in 1991—characterized as “barbarous and delicate.” An ambulance pulls up to unload a patient in front of a half-abandoned hospital in the midst of shutting down: “slippers in a crate with ampules of potassium chloride . . . a basin from an intensive care unit with a coating of snow on the bottom.” At another hospital, the nurses who draw his blood for the dreaded regular T-cell count “slip on their latex gloves as though they were velvet gloves for a gala evening at the opera.” One of them comments on his cologne, “It’s Habit Rouge isn’t it? . . . I do like that perfume, and to catch a whiff of it on this gray morning, well, you know it’s really a little treat for me.” Disease, as those who’ve spent time in the presence of the sick know, is never quite dramatically life or death, but always life in death and death in life. No moment of one’s life as a terminally ill person or a carer for a terminally ill person passes without this double acknowledgment.

The style of To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life is more restrained and controlled than these earlier works, but full of well-noticed contrasting details that combine to create an effect that Guibert—apropos of The Compassion Protocol, his last work before his suicide in 1991—characterized as “barbarous and delicate.” An ambulance pulls up to unload a patient in front of a half-abandoned hospital in the midst of shutting down: “slippers in a crate with ampules of potassium chloride . . . a basin from an intensive care unit with a coating of snow on the bottom.” At another hospital, the nurses who draw his blood for the dreaded regular T-cell count “slip on their latex gloves as though they were velvet gloves for a gala evening at the opera.” One of them comments on his cologne, “It’s Habit Rouge isn’t it? . . . I do like that perfume, and to catch a whiff of it on this gray morning, well, you know it’s really a little treat for me.” Disease, as those who’ve spent time in the presence of the sick know, is never quite dramatically life or death, but always life in death and death in life. No moment of one’s life as a terminally ill person or a carer for a terminally ill person passes without this double acknowledgment. ALONE AND INSIDE IN THESE

ALONE AND INSIDE IN THESE  Human beings typically don’t leave the nest until well into our teenage years—a relatively rare strategy among animals. But corvids—a group of birds that includes jays, ravens, and crows—also spend a lot of time under their parents’ wings. Now, in a parallel to humans, researchers have found that ongoing tutelage by patient parents may explain how corvids have managed to achieve their smarts. Corvids are large, big-brained birds that often live in intimate social groups of related and unrelated individuals. They are known to be intelligent—capable of

Human beings typically don’t leave the nest until well into our teenage years—a relatively rare strategy among animals. But corvids—a group of birds that includes jays, ravens, and crows—also spend a lot of time under their parents’ wings. Now, in a parallel to humans, researchers have found that ongoing tutelage by patient parents may explain how corvids have managed to achieve their smarts. Corvids are large, big-brained birds that often live in intimate social groups of related and unrelated individuals. They are known to be intelligent—capable of  In The Weil Conjectures Karen Olsson presents her remarkable subjects as creatures from a fairy tale: “Once there were a brother and sister who devoted themselves to the search for truth. A brother who spent his long life solving problems. A sister who died before she could solve the problem of life.” The sister was Simone Weil (pronounced “vay”), a philosopher and political activist who died in 1943 at age thirty-four and gained fame with the posthumous publication of works, assembled from her voluminous notebooks, on society, justice, and the mystical life of faith. Her elder brother André, who lived to ninety-two, was a prodigy who became one of the twentieth century’s preeminent mathematicians.

In The Weil Conjectures Karen Olsson presents her remarkable subjects as creatures from a fairy tale: “Once there were a brother and sister who devoted themselves to the search for truth. A brother who spent his long life solving problems. A sister who died before she could solve the problem of life.” The sister was Simone Weil (pronounced “vay”), a philosopher and political activist who died in 1943 at age thirty-four and gained fame with the posthumous publication of works, assembled from her voluminous notebooks, on society, justice, and the mystical life of faith. Her elder brother André, who lived to ninety-two, was a prodigy who became one of the twentieth century’s preeminent mathematicians. Late one January

Late one January