Rafia Zakaria in Baffler:

THE FIRST TIME MOHANDAS GANDHI, the leader of nonviolent protest against British rule in India, wrote to Adolf Hitler was in July of 1939. Gandhi was almost seventy. The world was, as it appears to be today, on the cusp of some huge transformation, although then, as now, the complete price of the change was unknown. “Dear friend,” Gandhi implored Hitler from behind a typewritten page, “friends have been urging me to write to you for the sake of humanity.” Hitler, the letter goes on to say, is the only “person in the world who can prevent a war which may reduce humanity to a savage state.”

THE FIRST TIME MOHANDAS GANDHI, the leader of nonviolent protest against British rule in India, wrote to Adolf Hitler was in July of 1939. Gandhi was almost seventy. The world was, as it appears to be today, on the cusp of some huge transformation, although then, as now, the complete price of the change was unknown. “Dear friend,” Gandhi implored Hitler from behind a typewritten page, “friends have been urging me to write to you for the sake of humanity.” Hitler, the letter goes on to say, is the only “person in the world who can prevent a war which may reduce humanity to a savage state.”

I can imagine Gandhi writing the letter, the humid air of an Indian July hanging heavy and oppressive, like the threat of war over the world. That first letter was barely over a hundred words, and it was never delivered. The British colonists who ruled India at the time minded Gandhi’s correspondence; they intercepted it well before it had any chance to reach Hitler. It is unknown whether Gandhi, an astute political strategist, knew this would be the case when he wrote the letter. He may have known that his audience was his own oppressors rather than the oppressors of European Jews. Whatever Gandhi’s motives, the appeal to Hitler was not new. The year before, American missionaries meeting with Gandhi pleaded with him to condemn Hitler and Mussolini, but he refused, insisting that no one, even these two fascists clearly uninterested in human dignity, was “beyond redemption.” Czechs and Jews were told to engage only in passive resistance, a sacrifice that would redeem them. Passive resistance failed to deliver either group, but Gandhi, for his part, never quite acknowledged this. (It was also not the only strategy they employed: consider the Warsaw Uprising of 1943, or the revolt at Auschwitz-Birkenau the following year.) Gandhi did write another, more vehement letter to Hitler, but this, too, was never delivered.

Gandhi got many things wrong about World War II. But in the days after George Floyd’s death, with protest ascendant, many reached for his prescriptions and other histories of nonviolent resistance, which present crucial questions about methods of opposition and defense. While there is much talk of the passive nonviolent resisters of old—Gandhi and his eventual disciple Martin Luther King Jr.—there is physical, psychic, and emotional violence being deliberately inflicted on the oppressed.

More here.

It was these writers in other genres who opened up possibilities for biography with a shift of focus from public to private. Chekhov invites this with his sense that “every individual existence is a mystery.” The title of Eliot’s verse drama, Murder in the Cathedral, teases us with the popular genre of the murder mystery, yet there is no mystery of the usual sort: Archbishop Thomas à Becket’s murder in 1170 takes place onstage, and the murderers are visible: four identifiable knights who are hit men for the king, Henry II. The real mystery lies in the inner life: Becket’s capacity for self-transformation. This is a biographical play about a twelfth-century saint in the making, as he readies himself for martyrdom by sloughing off his public life together with the outlived temptations of his former worldliness and ambition.

It was these writers in other genres who opened up possibilities for biography with a shift of focus from public to private. Chekhov invites this with his sense that “every individual existence is a mystery.” The title of Eliot’s verse drama, Murder in the Cathedral, teases us with the popular genre of the murder mystery, yet there is no mystery of the usual sort: Archbishop Thomas à Becket’s murder in 1170 takes place onstage, and the murderers are visible: four identifiable knights who are hit men for the king, Henry II. The real mystery lies in the inner life: Becket’s capacity for self-transformation. This is a biographical play about a twelfth-century saint in the making, as he readies himself for martyrdom by sloughing off his public life together with the outlived temptations of his former worldliness and ambition.

I

I THE FIRST TIME MOHANDAS GANDHI

THE FIRST TIME MOHANDAS GANDHI One of the most crucial questions about an emerging infectious disease such as the new coronavirus is how deadly it is. After months of collecting data, scientists are getting closer to an answer. Researchers use a metric called infection fatality rate (IFR) to calculate how deadly a new disease is. It is the proportion of infected people who will die as a result, including those who don’t get tested or show symptoms. “The IFR is one of the important numbers alongside the herd immunity threshold, and has implications for the scale of an epidemic and how seriously we should take a new disease,” says Robert Verity, an epidemiologist at Imperial College London.

One of the most crucial questions about an emerging infectious disease such as the new coronavirus is how deadly it is. After months of collecting data, scientists are getting closer to an answer. Researchers use a metric called infection fatality rate (IFR) to calculate how deadly a new disease is. It is the proportion of infected people who will die as a result, including those who don’t get tested or show symptoms. “The IFR is one of the important numbers alongside the herd immunity threshold, and has implications for the scale of an epidemic and how seriously we should take a new disease,” says Robert Verity, an epidemiologist at Imperial College London.

Sometimes it seems life can’t get any worse in this country. Already in terror of a pandemic, Americans have lately been bombarded with images of grotesque state-sponsored violence, from the murder of George Floyd to countless

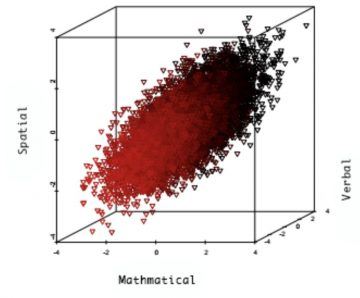

Sometimes it seems life can’t get any worse in this country. Already in terror of a pandemic, Americans have lately been bombarded with images of grotesque state-sponsored violence, from the murder of George Floyd to countless  Lev Landau, a Nobelist and one of the fathers of a great school of Soviet physics, had a logarithmic scale for ranking theorists, from 1 to 5. A physicist in the first class had ten times the impact of someone in the second class, and so on. He modestly ranked himself as 2.5 until late in life, when he became a 2. In the first class were Heisenberg, Bohr, and Dirac among a few others. Einstein was a 0.5!

Lev Landau, a Nobelist and one of the fathers of a great school of Soviet physics, had a logarithmic scale for ranking theorists, from 1 to 5. A physicist in the first class had ten times the impact of someone in the second class, and so on. He modestly ranked himself as 2.5 until late in life, when he became a 2. In the first class were Heisenberg, Bohr, and Dirac among a few others. Einstein was a 0.5! Six errors: 1) missing the compounding effects of masks, 2) missing the nonlinearity of the probability of infection to viral exposures, 3) missing absence of evidence (of benefits of mask wearing) for evidence of absence (of benefits of mask wearing), 4) missing the point that people do not need governments to produce facial covering: they can make their own, 5) missing the compounding effects of statistical signals, 6) ignoring the Non-Aggression Principle by pseudolibertarians (masks are also to protect others from you; it’s a multiplicative process: every person you infect will infect others).

Six errors: 1) missing the compounding effects of masks, 2) missing the nonlinearity of the probability of infection to viral exposures, 3) missing absence of evidence (of benefits of mask wearing) for evidence of absence (of benefits of mask wearing), 4) missing the point that people do not need governments to produce facial covering: they can make their own, 5) missing the compounding effects of statistical signals, 6) ignoring the Non-Aggression Principle by pseudolibertarians (masks are also to protect others from you; it’s a multiplicative process: every person you infect will infect others). This pandemic is closer to a disruption than a crisis or emergency. While all three refer to unexpected and dangerous events requiring immediate action not all involve a rupture. Crises and emergencies have become chronic conditions in finance and politics. This is why we prepare for them through financial contingency plans, safety drills, and disseminating information for the public. These, according to some political scientists, can also socialize people into better democratic habits and attitudes. Disruptions, by contrast, are meant to tear apart our existence. To take a prominent contemporary example, think of the industries that Uber and Amazon have disrupted by offering cheaper services and products.

This pandemic is closer to a disruption than a crisis or emergency. While all three refer to unexpected and dangerous events requiring immediate action not all involve a rupture. Crises and emergencies have become chronic conditions in finance and politics. This is why we prepare for them through financial contingency plans, safety drills, and disseminating information for the public. These, according to some political scientists, can also socialize people into better democratic habits and attitudes. Disruptions, by contrast, are meant to tear apart our existence. To take a prominent contemporary example, think of the industries that Uber and Amazon have disrupted by offering cheaper services and products. The last class Joel Sanders taught in person at the Yale School of Architecture, on Feb. 17, took place in the modern wing of the Yale University Art Gallery, a structure of brick, concrete, glass and steel that was designed by Louis Kahn. It is widely hailed as a masterpiece. One long wall, facing Chapel Street, is windowless; around the corner, a short wall is all windows. The contradiction between opacity and transparency illustrates a fundamental tension museums face, which happened to be the topic of Sanders’s lecture that day: How can a building safeguard precious objects and also display them? How do you move masses of people through finite spaces so that nothing — and no one — is harmed?

The last class Joel Sanders taught in person at the Yale School of Architecture, on Feb. 17, took place in the modern wing of the Yale University Art Gallery, a structure of brick, concrete, glass and steel that was designed by Louis Kahn. It is widely hailed as a masterpiece. One long wall, facing Chapel Street, is windowless; around the corner, a short wall is all windows. The contradiction between opacity and transparency illustrates a fundamental tension museums face, which happened to be the topic of Sanders’s lecture that day: How can a building safeguard precious objects and also display them? How do you move masses of people through finite spaces so that nothing — and no one — is harmed? Annie Zaidi was already a writer of renown in Mumbai when, in 2019, she submitted a 3,000-word essay to the

Annie Zaidi was already a writer of renown in Mumbai when, in 2019, she submitted a 3,000-word essay to the

Mathew Lawrence, Adrienne Buller, Joseph Baines & Sandy Hager over at Common Wealth:

Mathew Lawrence, Adrienne Buller, Joseph Baines & Sandy Hager over at Common Wealth: Branko Milanovic over at his website, Global Inequality:

Branko Milanovic over at his website, Global Inequality: Erik D’Amato reviews Alex Cooley and Dan Nexon’s new book, Exit from Hegemony: The Unraveling of the American Global Order in The LA Review of Books:

Erik D’Amato reviews Alex Cooley and Dan Nexon’s new book, Exit from Hegemony: The Unraveling of the American Global Order in The LA Review of Books: