by Thomas O’Dwyer

As Valentine’s Day fades away and the world returns to slippery gender normality, many Western men may still have some nagging questions. What did I do wrong this time? What do women want? Are we still on trial here? Older men may mutter that the male half of the young population has changed from manly men into little boys lost. Well, they have no one to blame but themselves. After centuries of entitled domination, some loutish cockerels have come home to roost. If manhood is on trial, it is for the bad attitudes, and worse, which it has long meted out to the other half of the population. Women are revolting only because male behaviour has been so revolting.

Yet, female rebellion is neither as new nor as rare as one might imagine. Women have often risen up against that most macho of male hobbies – warfare. The most famous example was the sex strike in the ancient Greek comedy Lysistrata by Aristophanes. Led by Lysistrata, the women withhold sex from their husbands as a strategy to end the Peloponnesian War.

In a modern re-enactment in 2003, Leymah Gbowee and the Women of Liberia Mass Action for Peace organized protests that included a sex strike. They brought peace to Liberia after a 14-year civil war and won the election of Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, the country’s first woman president. (Ms. Gbowee won the 2011 Nobel Peace Prize).

And in Ireland, there was The Midnight Court. In 1780 the poet Brian Merriman penned an epic saga in which the women of Ireland put their men on trial. It was for a different type of bad behaviour – for not providing enough sex and avoiding marriage. In less skilled hands, this literary work would have been long forgotten as another male fantasy about female lust. But it lives on in multiple modern translations from its medieval Irish – they are always in print in many European languages and even in Japanese.

Controversial from the outset, The Midnight Court can still spark as many disputes as the 1,000 lines it contains. Merriman has been lauded as a proto-feminist and condemned (by the Irish Church) as a dirty old man. Éamon de Valera, the freedom fighter and first leader of an independent Ireland, famously memorized the entire poem in the Irish original while he was in England’s Lincoln prison. Years later his own government banned Frank O’Connor’s English translation at the behest of the church. In Ireland, such bans were called “honourable dishonour.” A writer’s work was not serious literature until it was banned. The poem is often adapted for the stage and one modern production in Ireland billed it as “A play to celebrate the rights of women. Rights to wholesome marriage and wholesome sex.” What is not controversial is that it remains the greatest comic poem in the history of Irish-language literature.

Merriman is almost as mysterious as the Greek poet Homer – little is known of his life. His epic poem, Cúirt An Mheán Oíche (koort un vaan ee-ha), would also, like Homer’s, have been part of an oral storytelling tradition. It was first printed in 1850, forty-five years after Merriman’s death. Born around 1747 in the western County Clare, Merriman spent his life as a small farmer and school math teacher. The Midnight Court is the only significant writing he left. Merriman lived in a pre-English-language part of Ireland, now long vanished. Although the country was Catholic (in a Celtic rather than Roman sort of way) the attitudes in the poem are medieval. That’s medieval in the manner of Geoffrey Chaucer and Francois Rabelais – humanist, bawdy, naturalist and funny.

It may seem odd that in The Midnight Court such earthy and robust female characters could spring from Catholic Ireland. But theirs is a forgotten Ireland, the country before the tragic Great Famine of 1845. It was also before the wave of Victorian prudery and Puritanism that swept in from England in the last quarter of the 19th century. Irish historian Seán Connolly has written: “The majority of the population appears to have placed relatively little emphasis on reticence in sexual matters. The Irish literature of the period had a distinctly earthy and ribald strain.”

The Irish-language speakers of the 18th century still owed more to Celtic legend and to the ancient Brehon Laws than they did to “churchy” Catholicism or English law. The women in the trial of The Midnight Court are daughters of those laws, which still have a reputation for being progressive in their treatment of women. (Brehons – jurists – could be male or female). Claims that these Celtic laws provided for equality between the sexes may be over-idealistic. But, modernist spin aside, such trends were present in Brehon laws on equal property division after divorce, and on punishments for spousal abuse.

The Midnight Court begins in the style of an aisling or vision poem – like the opening of Dante’s Divine Comedy. This convention was already a cliché in Merriman’s day – similar to the routine of old Blues songs that begin “Well I woke up this mornin’ ” – and the poet neatly upends it. The poem is in five parts.

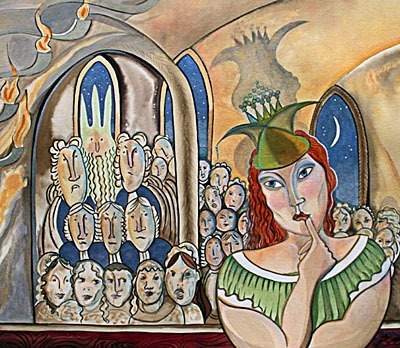

In part one, the poet is out on an evening walk and rests under a tree, when he has a vision of a woman from the other world. This beautiful woman usually would be Ireland and she would lament her lot and call on the nation’s sons to rise up against foreign occupation. Merriman takes a satirical and ironic twist. It’s a hideous female giant that appears and drags him kicking and screaming to the court of the Fairy Queen Aoibheal (Ee-vul). On the way to the court in a ruined monastery, the woman explains that the queen is disgusted by the corruptions of English law and landlords. As a brehon, she will henceforth dispense justice herself. It will be:

No court of robbers and spoilers strong

To maintain the bane of fraud and wrong,

But the court of the poor and lowly-born,

The court of women and folk forlorn.

In part two, a traditional court case opens under Brehon law as a three-part debate. It begins with a young woman pleading her complaints before the court – she is without a mate because the young men of the country refuse to marry. She says she is distraught by her desperate attempts to find a husband. She flirts madly at sports and social events but the young men ignore her in favour of later marriages to much older, wealthier, women:

And if one of them in the heat of youth

Ties up with a woman, she won’t be a lass

Full of vigour and wit, or a lady with class,

Or a beauty endowed with a shapely physique,

Or a budding young scribe of poetic mystique,

But a mangey old bag or a hatchet-faced bitch,

Who’ll go to her grave undeservedly rich.

In part three, an old man jumps up to counter the woman. In familiar man-in-court style, he attacks the woman’s reputation. He mansplains how young women create their own problems through their wanton promiscuity. He alleges that she herself was conceived by a tramp under a farm cart:

You slut of ill-fame, allow your betters

To tell the court how you learned your letters!

Your seed and breed for all your brag

Were tramps to a man with rag and bag;

I knew your Da and what passed for his wife

And he shouldered his carts to the end of his life.

The old man recounts the infidelity of his own young wife, whom he found was pregnant on their wedding night and he bemoans the persistent rumours about the “premature” birth of “his” son. Despite this, he insists there is nothing wrong with illegitimate children and denounces marriage as “out of date.” He asks Queen Aoibheal to outlaw it and to replace it with a system of free love. He argues that unbridled copulation would reverse the population decline and bring forth a new generation of Irish heroes like those of legend.

In part four, the young woman, now infuriated, takes the stand again after trying to physically attack the old man. She mocks his inability to satisfy a young wife who had only married him to avoid poverty:

Was it too much to expect as right

A little attention once a night?

From all I know she was never accounted

A woman too modest to be mounted.

She suggests that his wife had taken a young lover, and good for her – she deserves the pleasure he gives her. She then attacks the church for imposing celibacy on priests, thus preventing a group of fine educated young men from becoming good husbands and fathers. She asks the queen to force young men to marry, and not to exclude priests from the edict.

In part five, Queen Aoibheal delivers her verdict on the issues raised before the court. Despite the many progressive ideas the plaintiffs suggested, it is a conservative and harsh judgment. She rules that all laymen must marry before the age of 21, or be subject to severe corporal punishment at the hands of Irish women:

To my mind, girl, you’ve stated your case

With point and force. You deserve redress.

So I here enact a law for women:

Unmated men turned twenty-one

To be sought, pursued, and hunted down,

Tied to this tree beside the headstone,

Their vests stripped off, their jackets ripped,

Their backs and arses scourged and whipped.

She advises them to target with equal vigour men who hate romance, homosexuals, and womanisers boasting of the notches on their bedposts. Aoibheal tells them to take care when they physically punish the men and not to damage their ability to father children. On priests, she says their celibacy is outside her mandate and advises women to be patient and to hope the pope might change the law.

The poet has been an indifferent observer, but his idle dream now flips into a nightmare. To his horror, the angry attention of the court swivels in his direction. The fuming young woman points at him by name and screams that he is 30 years old and is still a selfish unattached bachelor. She says she had tired herself out with many attempts to attract his interest and steer him towards marrying her. She demands that he should be the first man to feel the wrath of the queen’s new marriage law by having his skin flayed off. A crowd of infuriated women prepares to flog him into a quivering jelly, and …

Readers down the centuries have been startled by the way Homer ended his vast epic, the Iliad, with one stark line:

Thus they buried Hector, tamer of horses.

In a similar abrupt ending to his comic saga, Merriman comes close to emulating the great Greek (or Alice in Wonderland):

I shivered and gave myself a shake,

Opened my eyes and was wide awake.

The Nobel laureate poet Seamus Heaney partially translated The Midnight Court. He then juxtaposed it with his translation of Orpheus and Eurydice by the Roman poet Ovid. At the end of the Merriman poem, Heaney placed his Death of Orpheus. In this, a horde of maenads, the crazy female followers of Dionysus, also descended on the poet and did tear him apart:

The oxen lowered their horns, the squealing maenads

Cut them to pieces, then turned to rend the bard,

Committing sacrilege when they ignored

His hands stretched out to plead and the extreme

Pitch of his song that now for the first time

Failed to enchant.

And so, alas, the breath

Of life streamed out of him, out of that mouth

Whose songs had tamed the beasts and made stones dance,

And was blown away on the indiscriminate winds.

Here Heaney cheekily implies a more satisfying, if gory, end for the unmarried Merriman in The Midnight Court. In the Orpheus story, a maenad first fingers the poet, as the young woman did to Merriman:

One of them whose hair streamed in the breeze

Began to shout, “Look, look, it’s Orpheus,

Orpheus the misogynist.”

Continue quavering in your boots, all you misogynists out there. And be careful where you sleep.

[Quotations used are from translations of Brian Merriman’s Cúirt An Mheán Oíche from the Irish by Arland Ussher, Frank O’Connor, Seamus Heaney and Ciaran Carson].