Category: Recommended Reading

Sailing to Byzantium read by Dermot Crowley

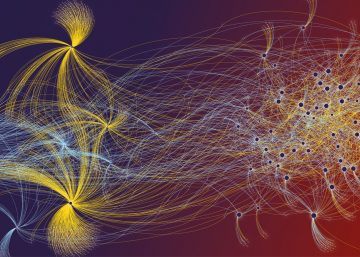

A new breed of researcher is turning to computation to understand society — and then change it

Heidi Ledford in Nature:

Elizaveta Sivak spent nearly a decade training as a sociologist. Then, in the middle of a research project, she realized that she needed to head back to school.

Elizaveta Sivak spent nearly a decade training as a sociologist. Then, in the middle of a research project, she realized that she needed to head back to school.

Sivak studies families and childhood at the National Research University Higher School of Economics in Moscow. In 2015, she studied the movements of adolescents by asking them in a series of interviews to recount ten places that they had visited in the past five days. A year later, she had analysed the data and was feeling frustrated by the narrowness of relying on individual interviews, when a colleague pointed her to a paper analysing data from the Copenhagen Networks Study, a ground-breaking project that tracked the social-media contacts, demographics and location of about 1,000 students, with five-minute resolution, over five months1. She knew then that her field was about to change. “I realized that these new kinds of data will revolutionize social science forever,” she says. “And I thought that it’s really cool.”

With that, Sivak decided to learn how to program, and join the revolution. Now, she and other computational social scientists are exploring massive and unruly data sets, extracting meaning from society’s digital imprint. They are tracking people’s online activities; exploring digitized books and historical documents; interpreting data from wearable sensors that record a person’s every step and contact; conducting online surveys and experiments that collect millions of data points; and probing databases that are so large that they will yield secrets about society only with the help of sophisticated data analysis.

More here.

Roberts Wanted Minimal Competence, but Trump Couldn’t Deliver

Adam Serwer in The Atlantic:

Two years ago, Chief Justice John Roberts gave the Trump administration a very important piece of advice: When you come to the Supreme Court, you need to do your homework. In his majority opinion sanctioning the Trump administration’s travel ban, Roberts disregarded Trump’s public statements that “Islam hates us,” and that America has problems “with Muslims coming into the country,” because the ultimate text of the travel ban issued by the administration “says nothing about religion.” Rather, Roberts wrote, the ban “reflects the results of a worldwide review process undertaken by multiple Cabinet officials and their agencies.” At the time, I found it shocking that the chief justice was essentially telling the Trump administration that it could turn the president’s prejudices into public policy with adequate lawyering and sufficient legal pretext. I assumed that the administration would do the necessary work of providing pretenses for its decisions, in order to achieve the policy outcome it desired. What I did not expect was that the Trump administration would not even bother to do that much.

Two years ago, Chief Justice John Roberts gave the Trump administration a very important piece of advice: When you come to the Supreme Court, you need to do your homework. In his majority opinion sanctioning the Trump administration’s travel ban, Roberts disregarded Trump’s public statements that “Islam hates us,” and that America has problems “with Muslims coming into the country,” because the ultimate text of the travel ban issued by the administration “says nothing about religion.” Rather, Roberts wrote, the ban “reflects the results of a worldwide review process undertaken by multiple Cabinet officials and their agencies.” At the time, I found it shocking that the chief justice was essentially telling the Trump administration that it could turn the president’s prejudices into public policy with adequate lawyering and sufficient legal pretext. I assumed that the administration would do the necessary work of providing pretenses for its decisions, in order to achieve the policy outcome it desired. What I did not expect was that the Trump administration would not even bother to do that much.

On Thursday, Roberts joined with the four Democratic appointees on the Court to invalidate the Trump administration’s decision to repeal the Obama-era Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals policy, which has shielded about 700,000 undocumented immigrants brought to the U.S. as children from deportation. The decision states that the Trump administration has the power to rescind the policy, but that the “arbitrary and capricious” manner in which it did so violated the Administrative Procedure Act, which governs decisions made by government agencies. The Department of Homeland Security, Roberts writes, was obliged to consider all of its options before repealing DACA wholesale. “Making that difficult decision was the agency’s job,” Roberts argues, “but the agency failed to do it.”

More here.

Friday Poem

These words of two, three years ago returned.

— Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, tr. by Will Petersen

Laughter

one day, Coyote sees Duck walking her ducklings,

Coyote asks her how she keeps them in a straight line,

Duck says she sews them together

with white horsetail hair every morning

and tugs on the line gently,

until the horsehair disappears,

that is how she keeps her ducklings in a row

as usual, Coyote leaves smiling, she sees a white horse

grazing in a nearby field,

she plucks a few strands of tail hair

and returns to her burrow

the next morning, one by one

she begins to sew her pups together

when she finishes, she gently tugs on the horsehair

and drags their little bodies along the ground,

Coyote tilts her head in dismay and becomes distraught,

she realizes she has killed her little pups

“Indians” will laugh about anything and anyone,

no matter the tragedy

by Chrisosto Apache

from Poetry

June , 2018

Thursday, June 18, 2020

The Intellectual Vocation

Joshua P. Hochschild in First Things:

Once upon a time, education was rhetorical training. Learning to think well, and thereby to negotiate all of life with responsible intelligence, was fundamentally about interacting with—drawing from and contributing to—a fund of powerful writing. But then, to make a long story short, things got complicated, “rhetoric” was demoted to one department among many, and that department was eventually rebranded as “Communication Studies.” In what could serve as a tragic epilogue to the history of Western education, young Mattie, son of the title character in Wendell Berry’s Hannah Coulter, goes off to study communication and becomes unable to talk to his own parents. “Communication of what?” asks Hannah’s husband, Nathan. “God knows what,” answers Hannah. “And that was about the extent of our conversation on that subject.”

Once upon a time, education was rhetorical training. Learning to think well, and thereby to negotiate all of life with responsible intelligence, was fundamentally about interacting with—drawing from and contributing to—a fund of powerful writing. But then, to make a long story short, things got complicated, “rhetoric” was demoted to one department among many, and that department was eventually rebranded as “Communication Studies.” In what could serve as a tragic epilogue to the history of Western education, young Mattie, son of the title character in Wendell Berry’s Hannah Coulter, goes off to study communication and becomes unable to talk to his own parents. “Communication of what?” asks Hannah’s husband, Nathan. “God knows what,” answers Hannah. “And that was about the extent of our conversation on that subject.”

It’s no surprise what Mattie missed in college. Anything like traditional rhetorical education is by now rare and usually accidental, and while some of us still try to keep alive a classical conception of “liberal education,” we sense a need for new rhetorical resources to capture what that is. Three new books about thinking testify that the old learning is ever-renewing, and available to anyone who knows what to look for.

Scott Newstok’s How to Think Like Shakespeare directly addresses rhetoric as “the craft of future discourse,” and attends to the particular practices that cultivate this craft.

More here.

René Girard – Violence and Religion

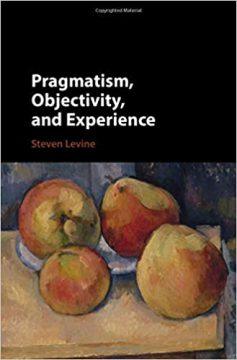

Pragmatism, Objectivity, and Experience

Robert Kraut at Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews:

Steven Levine has written a superb book. The title advertises three perennially puzzling topics: pragmatism, objectivity, and experience. Some background will help locate his project on a larger map.

Steven Levine has written a superb book. The title advertises three perennially puzzling topics: pragmatism, objectivity, and experience. Some background will help locate his project on a larger map.

Precise specification of pragmatism would be useful, but difficult to provide: a wide variety of views tend to appear under the pragmatist rubric. Frequently it involves little more than homage paid to the work of James, Peirce, and/or Dewey. More robust versions stress doctrinal and/or methodological views about truth and reference (e.g., the rejection of truth-as-correspondence-to-reality, or a more thoroughgoing deflationism about semantic discourse); other versions foreground the primacy of institutional norms, the impossibility of epistemically privileged representation, the significance of justificatory holism, rejection of the Enlightenment tradition built upon the pursuit of objective truth, the epistemic credentials of intuitions, and/or the folly of seeking to “ground” institutional practices in facts about confrontations with ontological realities which somehow “make normative demands” upon participants.

more here.

Do signals from beneath an Italian mountain herald a revolution in physics?

Dennis Overbye in the New York Times:

A team of scientists hunting dark matter has recorded suspicious pings coming from a vat of liquid xenon underneath a mountain in Italy. They are not claiming to have discovered dark matter — or anything, for that matter — yet. But these pings, they say, could be tapping out a new view of the universe.

A team of scientists hunting dark matter has recorded suspicious pings coming from a vat of liquid xenon underneath a mountain in Italy. They are not claiming to have discovered dark matter — or anything, for that matter — yet. But these pings, they say, could be tapping out a new view of the universe.

If the signal is real and persists, the scientists say, it may be evidence of a species of subatomic particles called axions — long theorized to play a crucial role in keeping nature symmetrical but never seen — streaming from the sun.

“It’s not dark matter but discovering a new particle would be phenomenal,” said Elena Aprile of Columbia University, who leads the Xenon Collaboration, the project that made the detection.

In a statement, the collaboration said that detecting the axions would have “a large impact on our understanding of fundamental physics, but also on astrophysical phenomena.”

More here.

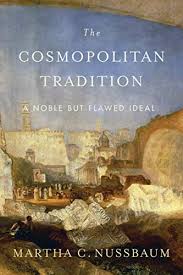

How Cosmopolitanism Became A Freighted Term

Stuart Whatley at The Hedgehog Review:

Nussbaum concludes that the cosmopolitan tradition “must be revised but need not be rejected.” She proposes that it be replaced by her own version of the “Capability Approach” to development. Conceived by the Nobel laureate economist Amartya Sen as an alternative to the prevailing mode of Western-exported market fundamentalism, the Capability Approach challenges the central tenets of economic globalization in its modern context: free trade, floating exchange rates, capital account and labor market “liberalization,” and so forth. In lieu of a sole focus on GDP and strictly monetary metrics of growth, the Capability Approach advocates a concern with the positive freedoms and opportunities that follow from investments in education, health care, leisure, environmental sustainability, and other factors.

Nussbaum concludes that the cosmopolitan tradition “must be revised but need not be rejected.” She proposes that it be replaced by her own version of the “Capability Approach” to development. Conceived by the Nobel laureate economist Amartya Sen as an alternative to the prevailing mode of Western-exported market fundamentalism, the Capability Approach challenges the central tenets of economic globalization in its modern context: free trade, floating exchange rates, capital account and labor market “liberalization,” and so forth. In lieu of a sole focus on GDP and strictly monetary metrics of growth, the Capability Approach advocates a concern with the positive freedoms and opportunities that follow from investments in education, health care, leisure, environmental sustainability, and other factors.

more here.

The American Soviet Mentality

Izabella Tabarovsky in Tablet:

Collective demonizations of prominent cultural figures were an integral part of the Soviet culture of denunciation that pervaded every workplace and apartment building. Perhaps the most famous such episode began on Oct. 23, 1958, when the Nobel committee informed Soviet writer Boris Pasternak that he had been selected for the Nobel Prize in literature—and plunged the writer’s life into hell. Ever since Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago had been first published the previous year (in Italy, since the writer could not publish it at home) the Communist Party and the Soviet literary establishment had their knives out for him. To the establishment, the Nobel Prize added insult to grave injury.

Collective demonizations of prominent cultural figures were an integral part of the Soviet culture of denunciation that pervaded every workplace and apartment building. Perhaps the most famous such episode began on Oct. 23, 1958, when the Nobel committee informed Soviet writer Boris Pasternak that he had been selected for the Nobel Prize in literature—and plunged the writer’s life into hell. Ever since Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago had been first published the previous year (in Italy, since the writer could not publish it at home) the Communist Party and the Soviet literary establishment had their knives out for him. To the establishment, the Nobel Prize added insult to grave injury.

Within days, Pasternak was a target of a massive public vilification campaign. The country’s prestigious Literary Newspaper launched the assault with an article titled “Unanimous Condemnation” and an official statement by the Soviet Writers’ Union—a powerful organization whose primary function was to exercise control over its members, including by giving access to exclusive benefits and basic material necessities unavailable to ordinary citizens.

More here.

A call for action from Arundhati Roy: “We need a reckoning”

Switch in Mouse Brain Induces a Deep Slumber Similar to Hibernation

Simon Makin in Scientific American:

A well-worn science-fiction trope imagines space travelers going into suspended animation as they head into deep space. Closer to reality are actual efforts to slow biological processes to a fraction of their normal rate by replacing blood with ice-cold saline to prevent cell death in severe trauma. But saline transfusions or other exotic measures are not ideal for ratcheting down a body’s metabolism because they risk damaging tissue.

A well-worn science-fiction trope imagines space travelers going into suspended animation as they head into deep space. Closer to reality are actual efforts to slow biological processes to a fraction of their normal rate by replacing blood with ice-cold saline to prevent cell death in severe trauma. But saline transfusions or other exotic measures are not ideal for ratcheting down a body’s metabolism because they risk damaging tissue.

Coaxing an animal into low-power mode on its own is a better solution. For some animals, natural states of lowered body temperature are commonplace. Hibernation is the obvious example. When bears, bats or other animals hibernate, they experience multiple bouts of a low-metabolism state called torpor for days at a time, punctuated by occasional periods of higher arousal. Mice enter a state known as daily torpor, lasting only hours, to conserve energy when food is scarce.

The mechanisms that control torpor and other hypothermic states—in which body temperatures drop below 37 degrees Celsius—are largely unknown. Two independent studies published in Nature on Thursday identify neurons that induce such states in mice when they are stimulated. The work paves the way toward understanding how these conditions are initiated and controlled. It could also ultimately help find methods for inducing hypothermic states in humans that will prove useful in medical settings. And more speculatively, such methods might one day approximate the musings about suspended animation that turn up in the movies.

More here.

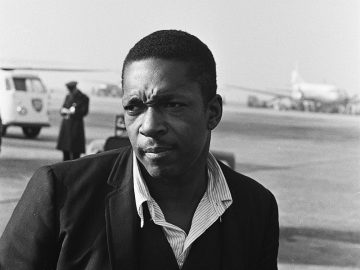

On John Coltrane’s “Alabama”

Ismael Muhammad in The Paris Review:

The John Coltrane Quartet’s “Alabama” is a strange song, incongruous with the rest of the album on which it appears. Inserted into Coltrane’s 1964 album Live at Birdland, it’s a studio track that confounds the virtuosic post-bop bliss of the album’s first three tracks, live recordings that include a jittery rendition of Mongo Santamaria’s “Afro Blue.” All of that collapses when we reach the sunken melancholy of “Alabama.” We are far, now, from the cascades of sound that Coltrane introduced us to in “Giant Steps,” far from the sonic innovations and precise phrasing he refined in this album’s live recordings. Here, Coltrane’s saxophone sounds hoarse and enfeebled, until it collapses on the threshold of a hole in the ground.

The John Coltrane Quartet’s “Alabama” is a strange song, incongruous with the rest of the album on which it appears. Inserted into Coltrane’s 1964 album Live at Birdland, it’s a studio track that confounds the virtuosic post-bop bliss of the album’s first three tracks, live recordings that include a jittery rendition of Mongo Santamaria’s “Afro Blue.” All of that collapses when we reach the sunken melancholy of “Alabama.” We are far, now, from the cascades of sound that Coltrane introduced us to in “Giant Steps,” far from the sonic innovations and precise phrasing he refined in this album’s live recordings. Here, Coltrane’s saxophone sounds hoarse and enfeebled, until it collapses on the threshold of a hole in the ground.

In “Alabama,” Coltrane asks us to bear witness to this hole in the ground, which is also a hole in America’s story, which is also a hole in the heart of black Americans. He wants us to grieve alongside him at this absence. The quartet recorded the track in November 1963, two months after the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, made an absence of four little black girls. When I listen to Coltrane playing over Tyner’s piano I hear smoke rising up from a smoldering crater, mingling with the voices of the dead. He asks us to peer down into the hole, to toss ourselves over into this absence. Just past the one-minute mark, even this funeral dirge collapses in on itself, as Coltrane’s saxophone sinks into a descending arpeggio, coaxing us in.

…I started listening to and thinking about “Alabama” a lot in the aftermath of Philando Castile’s murder in the summer of 2016, which was reminiscent of the murders of Samuel DuBose, Alton Sterling, Terence Crutcher, Walter Scott, Jamar Clark, Sandra Bland, and countless others. I’d lay down and loop the song through my bedroom speakers because the sonic landscape that Coltrane conjures on the track suggests something about the temporality in which black grief lives, the way that black people are forced to grieve our dead so often that the work of grieving never ends. You don’t even have time to grieve one new absence before the next one arrives. (We hadn’t time to grieve Ahmaud Arbery before we saw the video of Floyd’s murder.) “Alabama” gives this unceasing immersion in grief a form. It’s there in the song’s disconcerting stops and starts, its disarticulated notes, its willingness to abandon virtuosity in favor of a style of playing that is repetitive, diffuse, tentative, and dissonant.

More here.

Thursday Poem

Playing the Nocturnes: #19 In E Minor, Opus Posthumous 71, No. 1: Andante

By the time we finally learn,

it’s too late: the clock of the body

turns over the hours,

the days, our faces,

like pages in a book –

half-glimpsed, half-known,

gone.

The clock of the heart has odd hitches

in its ticking, missed beats,

and between them,

timeless –

our fingers, fragile deer running

through forests of soft hair,

that glance over a shoulder,

fragments of song –

and then the drum keeps drumming, then

the march over the edge.

And we’re always

leaping,

the sonata half-memorized,

our fingers, old or young, so clumsy

with desire – grass, pear, belly,

pine, we’re too small

to hold it.

We do what caught animals do –

we press against the walls

and they give way:

this life, no body can contain

or outlast it,

and who knows

if stars know what love is

or if God remembers anything

beyond that first loneliness,

that first division

between water

and light.

by B.J. Buckley

from The Ecotheo Review

Wednesday, June 17, 2020

Interview with Nikil Saval, former n+1 editor and projected winner of a Pennsylvania state senate seat, explains why so many lawyers run for office and writers don’t

Editor’s Note: Nikil Saval is now the confirmed winner of the state senate seat.

Gabriella Paiella in GQ:

Last summer, Nikil Saval was best known as a head editor for the literary and political magazine n+1. He wrote freelance articles about architecture and design for The New York Times and The New Yorker. He used a Motorola razr flip phone.

Last summer, Nikil Saval was best known as a head editor for the literary and political magazine n+1. He wrote freelance articles about architecture and design for The New York Times and The New Yorker. He used a Motorola razr flip phone.

A year later, Saval’s life looks markedly different. Last week he was declared the projected winner of the Democratic primary in Pennsylvania’s 1st Senate District against 12-year incumbent Larry Farnese, joining the wave of democratic socialist candidates triumphing in down-ballot races in Pennsylvania and across the country. He had also since upgraded to a smartphone.

“I couldn’t receive group texts. I couldn’t receive images, and that turns out to be important,” he tells GQ. “Thus, we had to do it.”

With 68% of the current tallied votes in his favor and no Republican challenger in the general election, Saval will, in all likelihood, be occupying the state senate seat come January.

More here.

The Ontology of Pop Physics

Adam Kirsch in Tablet:

The World According to Physics, by the British physicist Jim Al-Khalili, looks less like a book that belongs in the science section of Barnes & Noble than one you might find in a hotel nightstand. There is no dustjacket, just the handsome blue cloth covers embossed with silver lettering, like a Bible. The title is self-consciously New Testament, following the formula of the Gospels according to Mark, Luke, Matthew, and John. And on the back cover, in lieu of the usual blurbs from fellow science writers, there are phrases of the kind that adorn proselytizers’ pamphlets: “The Knowledge We Have Revealed,” “The True Nature of Reality, Illuminated.”

The World According to Physics, by the British physicist Jim Al-Khalili, looks less like a book that belongs in the science section of Barnes & Noble than one you might find in a hotel nightstand. There is no dustjacket, just the handsome blue cloth covers embossed with silver lettering, like a Bible. The title is self-consciously New Testament, following the formula of the Gospels according to Mark, Luke, Matthew, and John. And on the back cover, in lieu of the usual blurbs from fellow science writers, there are phrases of the kind that adorn proselytizers’ pamphlets: “The Knowledge We Have Revealed,” “The True Nature of Reality, Illuminated.”

These design choices help to surface a tension found in most popular books about physics and cosmology—a genre I started to read avidly a couple of years ago. Though they are explicitly anti-religious, such books function as religious texts. We turn to them in the same way that people once turned to collections of sermons or scriptural exegeses, in search of the fundamental truths that structure our world.

More here.

John Spence: How Einstein Abolished the Aether

How Pyrrhonism, a branch of ancient skepticism, can help us navigate today’s turbulent waters

Rachel Ashcroft in Arc Digital:

Even the way in which coronavirus data is presented can radically change our perception of its impact, depending on which factors have been included and which have been discarded.

Even the way in which coronavirus data is presented can radically change our perception of its impact, depending on which factors have been included and which have been discarded.

The confusion over what works and what doesn’t can leave us feeling deeply overwhelmed.

It’s little wonder, then, that in this anxiety-riddled time many are turning to Stoicism and its promise of courage and calm. However, I’d like to recommend something different. Pyrrhonism, a lesser-known philosophy from the same time as Stoicism, argues that we don’t know how things around us really are. Let’s give it a closer look, since this seems to be the very epistemic position we seem to find ourselves in today.

More here.

Turkish Female Singers and Anatolian Pop