Category: Recommended Reading

John Kennedy Toole @50

James McWilliams at Public Books:

The New York publishers were wrong. A Confederacy of Dunces did, in fact, make a point, a fundamental one. Percy grasped it immediately: the book was a screed against American materialism and optimism, a defense of the oddball outcasts who live on the fringes and resist the push of progress, and a celebration of those who try to drop out with dignity.

The New York publishers were wrong. A Confederacy of Dunces did, in fact, make a point, a fundamental one. Percy grasped it immediately: the book was a screed against American materialism and optimism, a defense of the oddball outcasts who live on the fringes and resist the push of progress, and a celebration of those who try to drop out with dignity.

The novel delivered one of American literature’s finest condemnations of a national obsession so pervasive that, with the exception of the South, the United States experienced it the way a fish experiences water: A Confederacy of Dunces challenged the whole idea of work. Toole’s critique begins and ends with the novel’s protagonist, the unprecedented antihero Ignatius J. Reilly. Ignatius, 30, is a flatulent and grandiose medievalist who lives with his mother, reads Boethius, and, between chronic bouts of masturbation and moviegoing, scribbles “a lengthy indictment against our century.”

more here.

The Mystery of Edwin Drood

Frances Wilson at Literary Review:

While he was writing Edwin Drood, Dickens was imbibing large quantities of opium, a drug that allows us, Thomas De Quincey explained in Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, access to a ‘second life’. Opium also allows the ‘guilty man’, De Quincey continued, to regain ‘for one night … the hopes of his youth, and hands washed pure of blood’. But at the same time as releasing the guilty man from his chains, taking opium causes further feelings of guilt. ‘In the one crime of OPIUM’, wailed Coleridge, whose life was destroyed by it, ‘what crime have I not made myself guilty of!’

While he was writing Edwin Drood, Dickens was imbibing large quantities of opium, a drug that allows us, Thomas De Quincey explained in Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, access to a ‘second life’. Opium also allows the ‘guilty man’, De Quincey continued, to regain ‘for one night … the hopes of his youth, and hands washed pure of blood’. But at the same time as releasing the guilty man from his chains, taking opium causes further feelings of guilt. ‘In the one crime of OPIUM’, wailed Coleridge, whose life was destroyed by it, ‘what crime have I not made myself guilty of!’

Dickens was the master of guilt: Little Dorrit’s Arthur Clenham is a study in the psychopathology of the guilty man, and so is John Jasper. But it was his own guilt that increasingly haunted Dickens, and the figure of Jasper was a disguised self-portrait.

more here.

Tuesday, June 23, 2020

Frans de Waal On Animal Intelligence And Emotions

Mark Leviton in The Sun:

Leviton: Darwin wrote that the difference in mind between humans and higher animals is “one of degree and not of kind.” What do you think he meant?

Leviton: Darwin wrote that the difference in mind between humans and higher animals is “one of degree and not of kind.” What do you think he meant?

De Waal: I think Darwin meant that the way we think is not fundamentally different from the way other species think, and I’m completely in agreement with him, even though people have attacked him for it over the years and said this was one of the things he was wrong about. There are some elements to human thought processes that are special, but the whole structure of cognition — how it works, what we can comprehend, how we find solutions to problems — is not so different. Human cognition is a variety of animal cognition.

Leviton: Why do you think some people have such a hard time accepting that idea?

De Waal: It’s strange, especially at a time when neuroscience is showing us the similarities between the monkey brain and the human brain. For instance, there’s no part of a human brain that you don’t also find in a monkey brain. There are no synapses or transmitters that are different. Even the blood supply is the same. We do have bigger brains, it’s true, which is certainly important.

Let me tell you a funny story about that.

More here.

Sean Carroll’s Mindscape Podcast: Maria Konnikova on Poker, Psychology, and Reason

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

The best chess and Go players in the world aren’t human beings any more; they’re artificially-intelligent computer programs. But the best poker players are still humans. Poker is a laboratory for understanding how rationality works in real-world situations: it features stochastic events, incomplete information, Bayesian updating, game theory, reading other people, a battle between emotions and reason, and real-world stakes. Maria Konnikova started in psychology, turned to writing, and then took up professional-level poker, and has learned a lot along the way about the challenges of being rational. We talk about what games like poker can teach us about thinking and human psychology.

The best chess and Go players in the world aren’t human beings any more; they’re artificially-intelligent computer programs. But the best poker players are still humans. Poker is a laboratory for understanding how rationality works in real-world situations: it features stochastic events, incomplete information, Bayesian updating, game theory, reading other people, a battle between emotions and reason, and real-world stakes. Maria Konnikova started in psychology, turned to writing, and then took up professional-level poker, and has learned a lot along the way about the challenges of being rational. We talk about what games like poker can teach us about thinking and human psychology.

More here.

The New Truth

Jacob Siegel in Tablet:

There are distinct and deep-rooted traditions of rational empiricism and religious sermonizing in American history. But these two modes seem to have become fused together in a new form of argumentation that is validated by elite institutions like the universities, The New York Times, Gracie Mansion, and especially on the new technology platforms where battles over the discourse are now waged. The new mode is argument by commandment: It borrows the form to game the discourse of rational argumentation in order to issue moral commandments. No official doctrine yet exists for this syncretic belief system but its features have been on display in all of the major debates over political morality of the past decade. Marrying the technical nomenclature of rational proof to the soaring eschatology of the sermon, it releases adherents from the normal bounds of reason. The arguer-commander is animated by a vision of secular hell—unremitting racial oppression that never improves despite myths about progress; society as a ceaseless subjection to rape and sexual assault; Trump himself, arriving to inaugurate a Luciferean reign of torture. Those in possession of this vision do not offer the possibility of redemption or transcendence, they come to deliver justice. In possession of justice, the arguer-commander is free at any moment to throw off the cloak of reason and proclaim you a bigot—racist, sexist, transphobe—who must be fired from your job and socially shunned.

There are distinct and deep-rooted traditions of rational empiricism and religious sermonizing in American history. But these two modes seem to have become fused together in a new form of argumentation that is validated by elite institutions like the universities, The New York Times, Gracie Mansion, and especially on the new technology platforms where battles over the discourse are now waged. The new mode is argument by commandment: It borrows the form to game the discourse of rational argumentation in order to issue moral commandments. No official doctrine yet exists for this syncretic belief system but its features have been on display in all of the major debates over political morality of the past decade. Marrying the technical nomenclature of rational proof to the soaring eschatology of the sermon, it releases adherents from the normal bounds of reason. The arguer-commander is animated by a vision of secular hell—unremitting racial oppression that never improves despite myths about progress; society as a ceaseless subjection to rape and sexual assault; Trump himself, arriving to inaugurate a Luciferean reign of torture. Those in possession of this vision do not offer the possibility of redemption or transcendence, they come to deliver justice. In possession of justice, the arguer-commander is free at any moment to throw off the cloak of reason and proclaim you a bigot—racist, sexist, transphobe—who must be fired from your job and socially shunned.

More here.

Daniel Kahneman, Steven Pinker and Shami Chakrabarti discuss Risk, rationality and coronavirus

In Methuselah’s Mould

Bill O’Neil in PLOS Biology:

The pathologist makes do with red wine until an effective drug is available, the biochemist discards the bread from her sandwiches, and the mathematician indulges in designer chocolate with a clear conscience. The demographer sticks to vitamin supplements, and while the evolutionary biologist calculates the compensations of celibacy, the population biologist transplants gonads, but so far only those of his laboratory mice. Their common cause is to control and extend the healthy lifespan of humans. They want to cure ageing and the diseases that come with it.

The pathologist makes do with red wine until an effective drug is available, the biochemist discards the bread from her sandwiches, and the mathematician indulges in designer chocolate with a clear conscience. The demographer sticks to vitamin supplements, and while the evolutionary biologist calculates the compensations of celibacy, the population biologist transplants gonads, but so far only those of his laboratory mice. Their common cause is to control and extend the healthy lifespan of humans. They want to cure ageing and the diseases that come with it.

…Extending Life

Although the life-enhancing effects of Sinclair’s polyphenols are so far confined to the baker’s yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the work suggests that researchers are only one small step from making a giant leap for humankind. “People imagined that it might have been possible, but few people thought that it was going to be possible so quickly to find such things,” says Sinclair. The field of ageing research is buzzing. Resveratrol stimulated a known activator of increased longevity in yeast, the enzyme Sir-2, and thereby extended the organism’s lifespan by 70% (Box 1). Sir-2 belongs to a family of proteins with members in higher organisms, including SIR-2.1, an enzyme that regulates lifespan in worms, and SIRT-1, the human enzyme that promotes cell survival (Figure 1). Though researchers still do not know whether SIRT-1, or “Sir-2 in humans,” as Sinclair puts it, has anything to do with longevity, there is a good chance that it does, judging by its pedigree. In any event, resveratrol proved to be a potent activator of the human enzyme. This might not be altogether surprising, at least not now, given that the polyphenol is already associated with health benefits in humans, notably the mitigation of such age-related defects as neurodegeneration, carcinogenesis, and atherosclerosis.

More here.

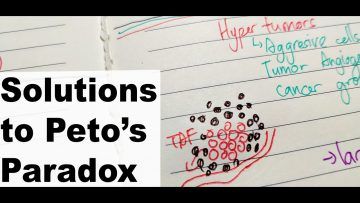

Why don’t all whales have cancer? A novel hypothesis resolving Peto’s paradox

John Nagy in Integrative and Comparative Biology:

Larger organisms have more potentially carcinogenic cells, tend to live longer and require more ontogenic cell divisions. Therefore, intuitively one might expect cancer incidence to scale with body size. Evidence from mammals, however, suggests that the cancer risk does not correlate with body size. This observation defines “Peto’s paradox.”

Larger organisms have more potentially carcinogenic cells, tend to live longer and require more ontogenic cell divisions. Therefore, intuitively one might expect cancer incidence to scale with body size. Evidence from mammals, however, suggests that the cancer risk does not correlate with body size. This observation defines “Peto’s paradox.”

Here, we propose a novel hypothesis to resolve Peto’s paradox. We suggest that malignant tumors are disadvantaged in larger hosts. In particular, we hypothesize that natural selection acting on competing phenotypes among the cancer cell population will tend to favor aggressive “cheaters” that then grow as a tumor on their parent tumor, creating a hypertumor that damages or destroys the original neoplasm. In larger organisms, tumors need more time to reach lethal size, so hypertumors have more time to evolve. So, in large organisms, cancer may be more common and less lethal. We illustrate this hypothesis in silico using a previously published hypertumor model. Results from the model predict that malignant neoplasms in larger organisms should be disproportionately necrotic, aggressive, and vascularized than deadly tumors in small mammals.

More here.

Tuesday Poem

In My Spare Time

During my long, boring hours of spare time

I sit to play with the earth’s sphere.

I establish countries without police or parties

and I scrap others that no longer attract consumers.

I run roaring rivers through barren deserts

and I create continents and oceans

that I save for the future just in case.

I draw a new colored map of the nations:

I roll Germany to the Pacific Ocean teeming with whales

and I let the poor refugees

sail pirates’ ships to her coasts

in the fog

dreaming of the promised garden in Bavaria.

I switch England with Afghanistan

so that its youth can smoke hashish for free

provided courtesy of Her Majesty’s government.

I smuggle Kuwait from its fenced and mined borders

to Comoro, the islands

of the moon in its eclipse,

keeping the oil fields in tact, of course.

At the same time I transport Baghdad

in the midst of loud drumming

to the islands of Tahiti.

I let Saudi Arabic crouch in its eternal desert

to preserve the purity of her thoroughbred camels.

This is before I surrender America

back to the Indians

just to give history

the justice it has long lacked.

I know that changing the world is not easy

but it remains necessary nonetheless.

by Fadhil al-Azzawi

from Poetry International

Translation: Khaled Mattawa

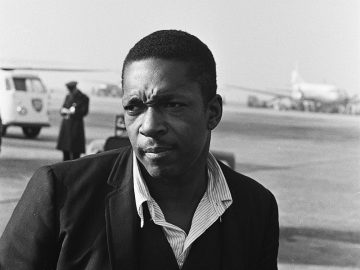

JOHN COLTRANE Alabama

Writing on Art and Muscle Memory

Louis Block at The Brooklyn Rail:

What brings me back to a painting is often a feeling, like a nagging muscle memory, of wanting not only to see, but to sense the painting’s facture. At the Met, I always return to Degas’s Portrait of a Woman in Gray (c. 1865), and the strange way in which the sitter’s black scarf seems to dominate the picture. Looking in closely, to the point where the weave of the canvas is visible and catching against the streaks of thinned oil, I find my wrist twitching with the desire to repeat the artist’s marks, anticipating the slight give of the fabric against the brushstroke, the soft friction of the bristles as they run out of pigment. It follows that my eyes’ movements are bound by this black shape that blends into the woman’s bonnet and resembles a figure holding an umbrella against the wind or wielding a scythe high in the air. Other portions of the painting seem secondary—the sketched-in right hand, the unfinished left eye—the whole composition just scaffolding for this burst of gesture. The tugging at my wrist lasts well after I leave the picture, each tightening of my fingers against the imaginary brush pulling the scarf back into focus.

What brings me back to a painting is often a feeling, like a nagging muscle memory, of wanting not only to see, but to sense the painting’s facture. At the Met, I always return to Degas’s Portrait of a Woman in Gray (c. 1865), and the strange way in which the sitter’s black scarf seems to dominate the picture. Looking in closely, to the point where the weave of the canvas is visible and catching against the streaks of thinned oil, I find my wrist twitching with the desire to repeat the artist’s marks, anticipating the slight give of the fabric against the brushstroke, the soft friction of the bristles as they run out of pigment. It follows that my eyes’ movements are bound by this black shape that blends into the woman’s bonnet and resembles a figure holding an umbrella against the wind or wielding a scythe high in the air. Other portions of the painting seem secondary—the sketched-in right hand, the unfinished left eye—the whole composition just scaffolding for this burst of gesture. The tugging at my wrist lasts well after I leave the picture, each tightening of my fingers against the imaginary brush pulling the scarf back into focus.

more here.

On John Coltrane’s “Alabama”

Ismail Muhammad at The Paris Review:

The John Coltrane Quartet’s “Alabama” is a strange song, incongruous with the rest of the album on which it appears. Inserted into Coltrane’s 1964 album Live at Birdland, it’s a studio track that confounds the virtuosic post-bop bliss of the album’s first three tracks, live recordings that include a jittery rendition of Mongo Santamaria’s “Afro Blue.” All of that collapses when we reach the sunken melancholy of “Alabama.” We are far, now, from the cascades of sound that Coltrane introduced us to in “Giant Steps,” far from the sonic innovations and precise phrasing he refined in this album’s live recordings. Here, Coltrane’s saxophone sounds hoarse and enfeebled, until it collapses on the threshold of a hole in the ground.

The John Coltrane Quartet’s “Alabama” is a strange song, incongruous with the rest of the album on which it appears. Inserted into Coltrane’s 1964 album Live at Birdland, it’s a studio track that confounds the virtuosic post-bop bliss of the album’s first three tracks, live recordings that include a jittery rendition of Mongo Santamaria’s “Afro Blue.” All of that collapses when we reach the sunken melancholy of “Alabama.” We are far, now, from the cascades of sound that Coltrane introduced us to in “Giant Steps,” far from the sonic innovations and precise phrasing he refined in this album’s live recordings. Here, Coltrane’s saxophone sounds hoarse and enfeebled, until it collapses on the threshold of a hole in the ground.

In “Alabama,” Coltrane asks us to bear witness to this hole in the ground, which is also a hole in America’s story, which is also a hole in the heart of black Americans.

more here.

Monday, June 22, 2020

3 Quarks Daily Welcomes Our New Monday Columnists

Hello Readers and Writers,

We received a large number of submissions of sample essays in our search for new columnists. Most of them were excellent and it was very hard deciding whom to accept and whom not to. If you did not get selected, it does not at all mean that we didn’t like what you sent; we just have a limited number of slots and also sometimes we have too many people who want to write about the same subject. Today we welcome to 3QD the following persons, in alphabetical order by last name:

- Usha Alexander

- Jackson Arn

- Varun Gauri

- Philip Graham

- Raji Jayaraman

- Alexander C. Kafka

- David Kordahl

- N. Gabriel Martin

- Eric Miller

- David Oates

- Mike O’Brien

- Godfrey Onime

- Paul Orlando

- Honora Spicer

- Jochen Szangolies

- Fabio Tollon

- Robyn Repko Waller

- Callum Watts

- Peter Wells

I will be in touch with all of you in the next days to schedule a start date. The “Monday Magazine” page will be updated with short bios and photographs of the new writers on the day they start.

Thanks to all of the people who sent samples of writing to us. It was a pleasure to read them all. Congratulations to the new writers!

Best wishes,

Abbas

Sunday, June 21, 2020

A pragmatist philosopher’s view of the US response to the coronavirus pandemic

Johnathan Flowers and Helen De Cruz in The Conversation:

Though many in the U.S. are disoriented and disheartened by the lack of an effective federal response to the coronavirus pandemic, John Dewey, an American philosopher, psychologist and educator, would not have been surprised.

Though many in the U.S. are disoriented and disheartened by the lack of an effective federal response to the coronavirus pandemic, John Dewey, an American philosopher, psychologist and educator, would not have been surprised.

Dewey presented a nuanced analysis of democracy, which we study as philosophers.

Dewey, who lived from 1859 to 1952, argued that democracies that put capitalism at their center, like the U.S., will march toward what he called a “bourgeois democracy.” This political system pays lip service to “government of, by, and for all the people,” and promises opportunities and freedom for all. But in reality, power is concentrated in the hands of industry and the economic elite.

Dewey outlined two characteristics of bourgeois democracy that can help explain the current U.S. federal response to the coronavirus: a focus on corporate interests, which many people have criticized for focusing on business and the economy, and an “us versus them” dynamic demonstrated in President Donald Trump’s response to the global aspects of the pandemic.

More here.

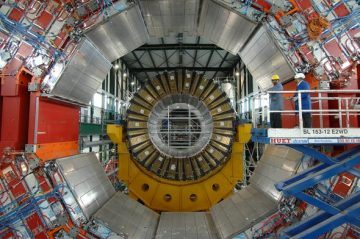

The World Doesn’t Need a New, Gigantic Particle Collider

Sabine Hossenfelder in Scientific American:

This is not the right time for a bigger particle accelerator. But CERN, the European physics center based in Geneva, Switzerland, has plans—big plans. The biggest particle physics facility of the world, currently running the biggest particle collider in the world, has announced it aims to build an even bigger machine, as revealed in a press conference and release today.

This is not the right time for a bigger particle accelerator. But CERN, the European physics center based in Geneva, Switzerland, has plans—big plans. The biggest particle physics facility of the world, currently running the biggest particle collider in the world, has announced it aims to build an even bigger machine, as revealed in a press conference and release today.

With that, CERN has decided it wants to go ahead with the first step of a plan for the Future Circular Collider (FCC), hosted in a ring-shaped tunnel 100 kilometers, or a bit over 60 miles, in circumference. This machine could ultimately reach collision energies of 100 tera-electron-volts, about six times the collision energy of the currently operating Large Hadron Collider (LHC). By reaching unprecedentedly high energies, the new collider would allow the deepest look into the structure of matter yet, and offer the possibility of finding new particles.

Whether the full vision will come into existence is still unclear. But CERN has announced it is of “high priority” for the organization to take the first step on the way to the FCC: finding a suitable site for the tunnel and building a machine to collide electrons and positrons at energies similar to that of the LHC (which however uses protons on protons).

More here.

Russian artist Ellen Sheidlin, known as Sheidlina, invites us to her creative, weird, and whimsical fantasy world

More here.

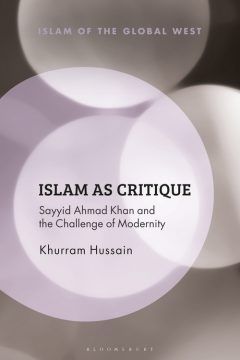

Islam as Critique: Sayyid Ahmad Khan and the Challenge of Modernity

Omar Farahat at Brill:

Khurram Hussain’s Islam as Critique: Sayyid Ahmad Khan and the Challenge of Modernity is an important and highly original book. At one level, the book is a fresh reading of some of Sayyid Aḥmad Khān’s (d. 1898) most profound intellectual contributions. At another, more important (at least for this reader) level, the book is an elaborate set of reflections on the place of Islam in the West and the place of (the study of) Islamic thought in modernity. The book’s offerings are daring and original, and the style is engaging. There are, inevitably, given the ambition of the project’s claims and the size of the book, areas in which one wishes the book offered a fuller discussion. Similarly, given the bold and very timely nature of the arguments, there are many venues that call for engagement to which we can and should respond. Thus, the book is obvious interest to scholars of South Asian Islam, Islamic thought, and broadly anyone concerned with the crises of modernity and alternative ways of being in the world, which, ideally, should be everyone.

Khurram Hussain’s Islam as Critique: Sayyid Ahmad Khan and the Challenge of Modernity is an important and highly original book. At one level, the book is a fresh reading of some of Sayyid Aḥmad Khān’s (d. 1898) most profound intellectual contributions. At another, more important (at least for this reader) level, the book is an elaborate set of reflections on the place of Islam in the West and the place of (the study of) Islamic thought in modernity. The book’s offerings are daring and original, and the style is engaging. There are, inevitably, given the ambition of the project’s claims and the size of the book, areas in which one wishes the book offered a fuller discussion. Similarly, given the bold and very timely nature of the arguments, there are many venues that call for engagement to which we can and should respond. Thus, the book is obvious interest to scholars of South Asian Islam, Islamic thought, and broadly anyone concerned with the crises of modernity and alternative ways of being in the world, which, ideally, should be everyone.

The book advances two primary sets of claims. The first pertains the properly contextualized reading of Khān’s thought as a response to the loss of Muslim sovereignty and identity in the subcontinent following the disastrous events of the mid-nineteenth century. Focusing on one major philosophical question after another, Hussain consistently shows that Khān’s project was an effort to piece together a coherent and viable identity and way of being in the world that systematically eschewed radical or idealized reactions.

More here.

Vera Lynn (1917 – 2020)

Frederick C. Tillis (1930 – 2020)