Veronique Greenwood and Quanta in The Atlantic:

The millimeter-long roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans has about 20,000 genes—and so do you. Of course, only the human in this comparison is capable of creating either a circulatory system or a sonnet, a state of affairs that made this genetic equivalence one of the most confusing insights to come out of the Human Genome Project. But there are ways of accounting for some of our complexity beyond the level of genes, and as one new study shows, they may matter far more than people have assumed.

The millimeter-long roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans has about 20,000 genes—and so do you. Of course, only the human in this comparison is capable of creating either a circulatory system or a sonnet, a state of affairs that made this genetic equivalence one of the most confusing insights to come out of the Human Genome Project. But there are ways of accounting for some of our complexity beyond the level of genes, and as one new study shows, they may matter far more than people have assumed.

For a long time, one thing seemed fairly solid in biologists’ minds: Each gene in the genome made one protein. The gene’s code was the recipe for one molecule that would go forth into the cell and do the work that needed doing, whether that was generating energy, disposing of waste, or any other necessary task. The idea, which dates to a 1941 paper by two geneticists who later won the Nobel Prize in medicine for their work, even has a pithy name: “one gene, one protein.”

Over the years, biologists realized that the rules weren’t quite that simple. Some genes, it turned out, were being used to make multiple products. In the process of going from gene to protein, the recipe was not always interpreted the same way. Some of the resulting proteins looked a little different from others. And sometimes those changes mattered a great deal. There is one gene, famous in certain biologists’ circles, whose two proteins do completely opposite things. One will force a cell to commit suicide, while the other will stop the process. And in one of the most extreme examples known to science, a single fruit fly gene provides the recipe for more than 38,000 different proteins.

More here.

In October, 2010, an Italian religious historian named Alberto Melloni stood over a small cherrywood box in the reading room of the Laurentian Library, in Florence. The box was old and slightly scuffed, and inked in places with words in Latin. It had been stored for several centuries inside one of the library’s distinctive sloping reading desks, which were designed by Michelangelo. Melloni slid the lid off the box. Inside was a yellow silk scarf, and wrapped in the scarf was a thirteenth-century Bible, no larger than the palm of his hand, which was falling to pieces. The Bible was “a very poor one,” Melloni told me recently. “Very dark. Very nothing.” But it had a singular history. In 1685, a Jesuit priest who had travelled to China gave the Bible to the Medici family, suggesting that it had belonged to Marco Polo, the medieval explorer who reached the court of Kublai Khan around 1275. Although the story was unlikely, the book had almost certainly been carried by an early missionary to China and spent several centuries there, being handled by scholars and mandarins—making it a remarkable object in the history of Christianity in Asia.

In October, 2010, an Italian religious historian named Alberto Melloni stood over a small cherrywood box in the reading room of the Laurentian Library, in Florence. The box was old and slightly scuffed, and inked in places with words in Latin. It had been stored for several centuries inside one of the library’s distinctive sloping reading desks, which were designed by Michelangelo. Melloni slid the lid off the box. Inside was a yellow silk scarf, and wrapped in the scarf was a thirteenth-century Bible, no larger than the palm of his hand, which was falling to pieces. The Bible was “a very poor one,” Melloni told me recently. “Very dark. Very nothing.” But it had a singular history. In 1685, a Jesuit priest who had travelled to China gave the Bible to the Medici family, suggesting that it had belonged to Marco Polo, the medieval explorer who reached the court of Kublai Khan around 1275. Although the story was unlikely, the book had almost certainly been carried by an early missionary to China and spent several centuries there, being handled by scholars and mandarins—making it a remarkable object in the history of Christianity in Asia. “No one in the world feels the weakness of general characterizing more than I.” So lamented Johann Gottfried von Herder, towering figure of the German Enlightenment, in his 1774 treatise This Too a Philosophy of History for the Formation of Humanity. “One draws together peoples and periods of time that follow one another in an eternal succession like waves of the sea,” Herder wrote. “Whom has one painted? Whom has the depicting word captured?” For Herder, the Enlightenment dream of grasping human history as a seamless whole came up against the irreducible particularity of individuals and cultures.

“No one in the world feels the weakness of general characterizing more than I.” So lamented Johann Gottfried von Herder, towering figure of the German Enlightenment, in his 1774 treatise This Too a Philosophy of History for the Formation of Humanity. “One draws together peoples and periods of time that follow one another in an eternal succession like waves of the sea,” Herder wrote. “Whom has one painted? Whom has the depicting word captured?” For Herder, the Enlightenment dream of grasping human history as a seamless whole came up against the irreducible particularity of individuals and cultures. In September 1991, a pair of German hikers in the Ötztal Alps, near the border between Austria and Italy, spotted something brown and human-shaped sticking out of a glacier. They immediately reported this to the authorities, thinking they had discovered the body of someone who had died while hiking. While they were correct about it being a dead body, they were a little off on the timing: what they found turned out to be the mummified corpse of a man who had died sometime before 3100 BCE.

In September 1991, a pair of German hikers in the Ötztal Alps, near the border between Austria and Italy, spotted something brown and human-shaped sticking out of a glacier. They immediately reported this to the authorities, thinking they had discovered the body of someone who had died while hiking. While they were correct about it being a dead body, they were a little off on the timing: what they found turned out to be the mummified corpse of a man who had died sometime before 3100 BCE. Since it emerged

Since it emerged  T

T Oates’s friend the novelist John Gardner once suggested that she try writing a story “in which things go well, for a change.” That hasn’t happened yet. Her latest book, the enormous and frequently brilliant “

Oates’s friend the novelist John Gardner once suggested that she try writing a story “in which things go well, for a change.” That hasn’t happened yet. Her latest book, the enormous and frequently brilliant “ The Sumerians were the first to develop a counting system to keep an account of their stock of goods – cattle, horses, and donkeys, for example. The Sumerian system was positional; that is, the placement of a particular symbol relative to others denoted its value. The Sumerian system was handed down to the Akkadians around 2500 BC and then to the Babylonians in 2000 BC. It was the Babylonians who first conceived of a mark to signify that a number was absent from a column; just as 0 in 1025 signifies that there are no hundreds in that number. Although zero’s Babylonian ancestor was a good start, it would still be centuries before the symbol as we know it appeared.

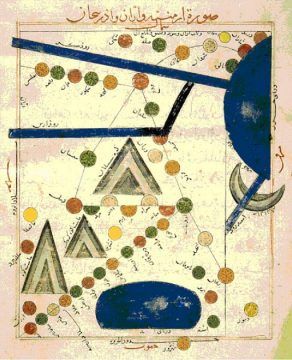

The Sumerians were the first to develop a counting system to keep an account of their stock of goods – cattle, horses, and donkeys, for example. The Sumerian system was positional; that is, the placement of a particular symbol relative to others denoted its value. The Sumerian system was handed down to the Akkadians around 2500 BC and then to the Babylonians in 2000 BC. It was the Babylonians who first conceived of a mark to signify that a number was absent from a column; just as 0 in 1025 signifies that there are no hundreds in that number. Although zero’s Babylonian ancestor was a good start, it would still be centuries before the symbol as we know it appeared. One of the greatest minds of the early mathematical production in Arabic was Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi (b. before 800, d. after 847 in Baghdad) who was a mathematician and astronomer as well as a geographer and a historian. It is said that he is the author in Arabic of one of the oldest astronomical tables, of one the oldest works on arithmetic and the oldest work on algebra; some of his scientific contributions were translated into Latin and were used until the 16th century as the principal mathematical textbooks in European universities. Originally he belonged to Khwârazm (modern Khiwa) situated in Turkistan but he carried on his scientific career in Baghdad and all his works are in Arabic.

One of the greatest minds of the early mathematical production in Arabic was Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi (b. before 800, d. after 847 in Baghdad) who was a mathematician and astronomer as well as a geographer and a historian. It is said that he is the author in Arabic of one of the oldest astronomical tables, of one the oldest works on arithmetic and the oldest work on algebra; some of his scientific contributions were translated into Latin and were used until the 16th century as the principal mathematical textbooks in European universities. Originally he belonged to Khwârazm (modern Khiwa) situated in Turkistan but he carried on his scientific career in Baghdad and all his works are in Arabic. Jan Rubens was in love, and then he was on the run. Once the affair with Anna of Saxony was discovered and Jan was arrested, he ran back to his wife, Peter Paul’s mother, begging her for forgiveness and for help. Who knows what was in the man’s heart? Maybe the whole ordeal created deep within the soul of Jan Rubens a love of his wife that had never existed before. Maybe the fog of love was lifted from his eyes, the fog of lust cleared away and gone too was the clouding monomania that sets in when a married man runs into the arms of another woman. Maybe one passion had overtaken the mind of Jan Rubens as he fell into this desperate affair with Anna of Saxony, an otherwise difficult woman as the contemporary sources say, and it made him forget about the rest of the world. He started to see everything through the lens of this clawing need, the need to be with Anna of Saxony, the need to manufacture more and more reasons that he spend time with her, work on projects with her, center his life around her. This became a demanding and unforgiving logic. He stopped asking why, he stopped considering his life in any other light than the light of need. He needed to be with Anna of Saxony, dearest Anna, the only woman alive.

Jan Rubens was in love, and then he was on the run. Once the affair with Anna of Saxony was discovered and Jan was arrested, he ran back to his wife, Peter Paul’s mother, begging her for forgiveness and for help. Who knows what was in the man’s heart? Maybe the whole ordeal created deep within the soul of Jan Rubens a love of his wife that had never existed before. Maybe the fog of love was lifted from his eyes, the fog of lust cleared away and gone too was the clouding monomania that sets in when a married man runs into the arms of another woman. Maybe one passion had overtaken the mind of Jan Rubens as he fell into this desperate affair with Anna of Saxony, an otherwise difficult woman as the contemporary sources say, and it made him forget about the rest of the world. He started to see everything through the lens of this clawing need, the need to be with Anna of Saxony, the need to manufacture more and more reasons that he spend time with her, work on projects with her, center his life around her. This became a demanding and unforgiving logic. He stopped asking why, he stopped considering his life in any other light than the light of need. He needed to be with Anna of Saxony, dearest Anna, the only woman alive. Bemoaning uneven individual and state compliance with public health recommendations, top U.S. COVID-19 adviser Anthony Fauci

Bemoaning uneven individual and state compliance with public health recommendations, top U.S. COVID-19 adviser Anthony Fauci  According to the

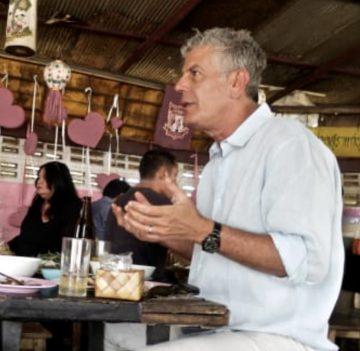

According to the  When crew from CNN’s “Anthony Bourdain: Parts Unknown” contacted me in February 2014 to ask for assistance with an upcoming shoot in Thailand, of course I agreed without hesitation.

When crew from CNN’s “Anthony Bourdain: Parts Unknown” contacted me in February 2014 to ask for assistance with an upcoming shoot in Thailand, of course I agreed without hesitation.