Albert and Mary Lasker Foundation Newsletter:

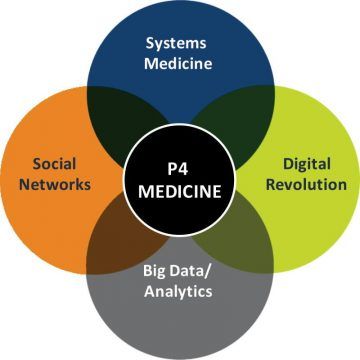

The highlights of Leroy Hood’s scientific career are like peaks in a mountain range spanning diverse fields, from molecular immunology and engineering, to genomics, to systems medicine. But Hood doesn’t think his trailblazing approach should be unusual, emphasizing that “one of the really key things about science is every 10 or 15 years, you really make a dramatic break and do something new… and you have to learn a lot before you can make fundamental contributions.”

The highlights of Leroy Hood’s scientific career are like peaks in a mountain range spanning diverse fields, from molecular immunology and engineering, to genomics, to systems medicine. But Hood doesn’t think his trailblazing approach should be unusual, emphasizing that “one of the really key things about science is every 10 or 15 years, you really make a dramatic break and do something new… and you have to learn a lot before you can make fundamental contributions.”

One of Hood’s early contributions was in cracking the long-standing mystery of how the immune systems of humans and all vertebrates give rise to the vast diversity of antibodies that is critical for fighting myriad pathogens and foreign substances. During his PhD research at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in the mid-1960s, Hood and his advisor, William Dreyer, determined the amino acid sequences of components of antibody molecules and found that their sequences varied greatly between different antibodies. The finding helped advance their idea that each antibody is actually encoded by more than one gene, a big challenge to the existing dogma. Later, with his own research group at Caltech, Hood detailed the intricate process of how segments of antibody-encoding genes are rearranged, further creating antibody diversity. For his work in this area, Hood, along with Philip Leder and Susumu Tonegawa, won the Albert Lasker Basic Medical Research Award in 1987.

Despite his groundbreaking discoveries in molecular immunology, Hood has not focused on this field for the last 20 years or so. Soon after starting his research group in 1970, he realized there were “striking technological limitations” that were holding scientists back from deeper understanding of the immune system. So, over the next two decades, Hood and his colleagues set out developing instruments, including the first automated DNA sequencer that allowed more rapid reads of genes. Hood’s intense focus on technology development as a faculty member at Caltech opened his eyes to what was the first paradigm shift of his career: “bringing engineering to biology.”

More here.

The term “

The term “ We know from every disaster movie that time is supposed to accelerate, not stand still, during a catastrophe. If asked to draw a scenario months ago, most of us would have imagined moments of chaos and disorder, akin to the profound social chaos in Florence during the plague as described by Boccaccio in his 14th-century work The Decameron, “all respect for the laws of God and man … broken down.”

We know from every disaster movie that time is supposed to accelerate, not stand still, during a catastrophe. If asked to draw a scenario months ago, most of us would have imagined moments of chaos and disorder, akin to the profound social chaos in Florence during the plague as described by Boccaccio in his 14th-century work The Decameron, “all respect for the laws of God and man … broken down.” Sudden, radical transformations of substances known to humanity for eons, like water freezing and soup steaming over a fire, remained mysterious until well into the 20th century. Scientists observed that substances typically change gradually: Heat a collection of atoms a little, and it expands a little. But nudge a material past a critical point, and it becomes something else entirely.

Sudden, radical transformations of substances known to humanity for eons, like water freezing and soup steaming over a fire, remained mysterious until well into the 20th century. Scientists observed that substances typically change gradually: Heat a collection of atoms a little, and it expands a little. But nudge a material past a critical point, and it becomes something else entirely. Scientism – the belief that science is the only valid source of knowledge and that all legitimate questions can be answered by science – is what spawns pseudoscience and science denialism. If science is treated as though it not only informs us but also dictates how our lives ought to be lived and how society ought to be run, then it is easier to peddle in the baseless denial of scientific claims than it is to challenge the illegitimate claim of authority over our choices made on science’s behalf.

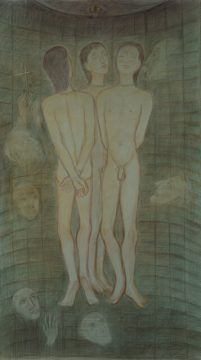

Scientism – the belief that science is the only valid source of knowledge and that all legitimate questions can be answered by science – is what spawns pseudoscience and science denialism. If science is treated as though it not only informs us but also dictates how our lives ought to be lived and how society ought to be run, then it is easier to peddle in the baseless denial of scientific claims than it is to challenge the illegitimate claim of authority over our choices made on science’s behalf. This is not to say that Klossowski was standoffish. One of the interesting things about him is that once you finally notice him you begin to see his shadowy presence everywhere in twentieth-century French culture. He was, for instance, an early French translator of Walter Benjamin—as well as Wittgenstein, Heidegger, and Kafka, among others. When very young, he was a secretary for André Gide and appears semidisguised as a character in Gide’s novel The Counterfeiters, a novel he appears to have helped edit and for which he also made illustrations (which were turned down for being too overtly erotic). The older brother of the painter Balthasar Klossowski de Rola, better known as Balthus, Klossowski was an artist himself, and his work is at once naïve and pornographically explicit in a way that sometimes references occult texts, mythology, and Klossowski’s own prose. He was a friend of Georges Bataille—and indeed Bataille’s own investigation of erotism might best be read in counterpoint to Klossowski. He was involved marginally with surrealists, spent time in a Dominican seminary, was later involved with the existentialists, and wrote philosophical texts on Friedrich Nietzsche and the Marquis de Sade that were influential for post-structuralism. His book-length economico-philosophical essay La Monnaie vivante (Living Currency) Foucault called “the best book of our times.” Fiction writer, philosopher, translator, and visual artist, Klossowski worked in many modes and media and seemed to touch the lives of many of the literary and artistic figures we now admire. Indeed, once he’s noticed, it’s hard not to suspect he’s lurking even where you don’t see him.

This is not to say that Klossowski was standoffish. One of the interesting things about him is that once you finally notice him you begin to see his shadowy presence everywhere in twentieth-century French culture. He was, for instance, an early French translator of Walter Benjamin—as well as Wittgenstein, Heidegger, and Kafka, among others. When very young, he was a secretary for André Gide and appears semidisguised as a character in Gide’s novel The Counterfeiters, a novel he appears to have helped edit and for which he also made illustrations (which were turned down for being too overtly erotic). The older brother of the painter Balthasar Klossowski de Rola, better known as Balthus, Klossowski was an artist himself, and his work is at once naïve and pornographically explicit in a way that sometimes references occult texts, mythology, and Klossowski’s own prose. He was a friend of Georges Bataille—and indeed Bataille’s own investigation of erotism might best be read in counterpoint to Klossowski. He was involved marginally with surrealists, spent time in a Dominican seminary, was later involved with the existentialists, and wrote philosophical texts on Friedrich Nietzsche and the Marquis de Sade that were influential for post-structuralism. His book-length economico-philosophical essay La Monnaie vivante (Living Currency) Foucault called “the best book of our times.” Fiction writer, philosopher, translator, and visual artist, Klossowski worked in many modes and media and seemed to touch the lives of many of the literary and artistic figures we now admire. Indeed, once he’s noticed, it’s hard not to suspect he’s lurking even where you don’t see him. For much of their history, intelligence tests have been rotten with the cultural and class biases of their makers, a diagnostic deck stacked against minorities, immigrants, and those at the bottom of the wage pyramid. Test designers have equated English-language fluency with intelligence, presumed a familiarity with upper-class pastimes such as tennis, and expected the examinee to provide the word “shrewd” as a synonym for “Jewish.” As late as the 1960 revision, the Stanford-Binet was presenting six-year-old children with crude cartoons of two women, one obviously Anglo-Saxon, the other a golliwog caricature of an African-American, with a broad nose and thick lips. The test accepted only one correct answer to the question, “Which is prettier?”12

For much of their history, intelligence tests have been rotten with the cultural and class biases of their makers, a diagnostic deck stacked against minorities, immigrants, and those at the bottom of the wage pyramid. Test designers have equated English-language fluency with intelligence, presumed a familiarity with upper-class pastimes such as tennis, and expected the examinee to provide the word “shrewd” as a synonym for “Jewish.” As late as the 1960 revision, the Stanford-Binet was presenting six-year-old children with crude cartoons of two women, one obviously Anglo-Saxon, the other a golliwog caricature of an African-American, with a broad nose and thick lips. The test accepted only one correct answer to the question, “Which is prettier?”12 A FEW LONG WEEKS AGO,

A FEW LONG WEEKS AGO,  In 2012, on a whim, Vincent Lynch decided to search the genome of the African elephant to see if it had extra anti-cancer genes. Cancers happen when cells build up mutations in their DNA that allow them to grow and divide uncontrollably. Bigger animals, whose bodies comprise more cells, should therefore have a higher risk of cancer. This is true within species: On average, taller humans are more likely to develop tumors than shorter ones, and bigger dogs have a higher cancer risk than smaller ones.

In 2012, on a whim, Vincent Lynch decided to search the genome of the African elephant to see if it had extra anti-cancer genes. Cancers happen when cells build up mutations in their DNA that allow them to grow and divide uncontrollably. Bigger animals, whose bodies comprise more cells, should therefore have a higher risk of cancer. This is true within species: On average, taller humans are more likely to develop tumors than shorter ones, and bigger dogs have a higher cancer risk than smaller ones.

Most people who catch the new coronavirus don’t experience severe symptoms, and some have no symptoms at all. COVID-19 saves its worst for relatively few.

Most people who catch the new coronavirus don’t experience severe symptoms, and some have no symptoms at all. COVID-19 saves its worst for relatively few. NC: The first thing that comes to mind is the absolutely unprecedented scope and scale of participation, engagement, and public support. If you look at polls, it’s astonishing. The

NC: The first thing that comes to mind is the absolutely unprecedented scope and scale of participation, engagement, and public support. If you look at polls, it’s astonishing. The  The cost of

The cost of  I’m recovering from flu, so I’ve spent more time than usual by myself lately, with odd ideas swirling around in my feverish brain. Recently a bunch of different thoughts–about

I’m recovering from flu, so I’ve spent more time than usual by myself lately, with odd ideas swirling around in my feverish brain. Recently a bunch of different thoughts–about