Patti Wigington in ThoughtCo:

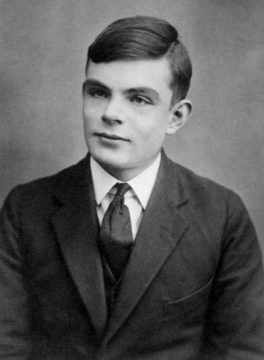

Alan Mathison Turing (1912 –1954) was one of England’s foremost mathematicians and computer scientists. Because of his work in artificial intelligence and codebreaking, along with his groundbreaking Enigma machine, he is credited with ending World War II. Turing’s life ended in tragedy. Convicted of “indecency” for his sexual orientation, Turing lost his security clearance, was chemically castrated, and later committed suicide at age 41.

Alan Mathison Turing (1912 –1954) was one of England’s foremost mathematicians and computer scientists. Because of his work in artificial intelligence and codebreaking, along with his groundbreaking Enigma machine, he is credited with ending World War II. Turing’s life ended in tragedy. Convicted of “indecency” for his sexual orientation, Turing lost his security clearance, was chemically castrated, and later committed suicide at age 41.

…During World War II, Bletchley Park was the home base of British Intelligence’s elite codebreaking unit. Turing joined the Government Code and Cypher School and in September 1939, when war with Germany began, reported to Bletchley Park in Buckinghamshire for duty. Shortly before Turing’s arrival at Bletchley, Polish intelligence agents had provided the British with information about the German Enigma machine. Polish cryptanalysts had developed a code-breaking machine called the Bomba, but the Bomba became useless in 1940 when German intelligence procedures changed and the Bomba could no longer crack the code. Turing, along with fellow code-breaker Gordon Welchman, got to work building a replica of the Bomba, called the Bombe, which was used to intercept thousands of German messages every month. These broken codes were then relayed to Allied forces, and Turing’s analysis of German naval intelligence allowed the British to keep their convoys of ships away from enemy U-boats.

…In addition to his codebreaking work, Turing is regarded as a pioneer in the field of artificial intelligence. He believed that computers could be taught to think independently of their programmers, and devised the Turing Test to determine whether or not a computer was truly intelligent. The test is designed to evaluate whether the interrogator can figure out which answers come from the computer and which come from a human; if the interrogator can’t tell the difference, then the computer would be considered “intelligent.”

…In 1952, Turing began a romantic relationship with a 19-year-old man named Arnold Murray. During a police investigation into a burglary at Turing’s home, he admitted that he and Murray were involved sexually. Because homosexuality was a crime in England, both men were charged and convicted of “gross indecency.” Turing was given the option of a prison sentence or probation with “chemical treatment” designed to reduce the libido. He chose the latter, and underwent a chemical castration procedure over the next twelve months. The treatment left him impotent and caused him to develop gynecomastia, an abnormal development of breast tissue. In addition, his security clearance was revoked by the British government, and he was no longer permitted to work in the intelligence field. In June 1954, Turing’s housekeeper found him dead. A post-mortem examination determined that he had died of cyanide poisoning, and the inquest ruled his death as suicide. A half-eaten apple was found nearby. The apple was never tested for cyanide, but it was determined to be the most likely method used by Turing.

More here.

In the first half of the 20th century, science fiction familiarized the world with the concept of artificially intelligent robots. It began with the “heartless” Tin man from the Wizard of Oz and continued with the humanoid robot that impersonated Maria in Metropolis. By the 1950s, we had a generation of scientists, mathematicians, and philosophers with the concept of artificial intelligence (or AI) culturally assimilated in their minds. One such person was Alan Turing, a young British polymath who explored the mathematical possibility of artificial intelligence. Turing suggested that humans use available information as well as reason in order to solve problems and make decisions, so why can’t machines do the same thing? This was the logical framework of his 1950 paper,

In the first half of the 20th century, science fiction familiarized the world with the concept of artificially intelligent robots. It began with the “heartless” Tin man from the Wizard of Oz and continued with the humanoid robot that impersonated Maria in Metropolis. By the 1950s, we had a generation of scientists, mathematicians, and philosophers with the concept of artificial intelligence (or AI) culturally assimilated in their minds. One such person was Alan Turing, a young British polymath who explored the mathematical possibility of artificial intelligence. Turing suggested that humans use available information as well as reason in order to solve problems and make decisions, so why can’t machines do the same thing? This was the logical framework of his 1950 paper,  Above all, Cockayne wants us to revise our assumption that people in the past must have been better at reuse and recycling (not the same thing) than we are today. There is, she insists, “no linear history of improvement”, no golden age when everyone automatically sorted their household scraps and spent their evenings turning swords into ploughshares because they knew it was the right thing to do. Indeed, in the 1530s the more stuff you threw away, the better you were performing your civic duty: refuse and surfeit was built into the semiotics of display in Henry VIII’s England, which explains why, on formal occasions, it was stylish to have claret and white wine running down the gutters. Three generations later and Oliver Cromwell’s Parliamentarian troops had found new ways to manipulate codes of waste and value. In 1646 they ransacked Winchester cathedral and sent all the precious parchments off to London to be made into kites “withal to fly in the air”.

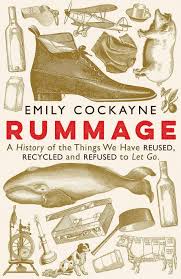

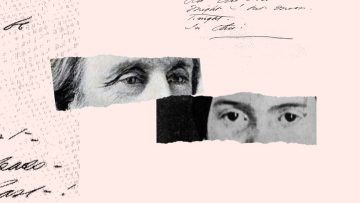

Above all, Cockayne wants us to revise our assumption that people in the past must have been better at reuse and recycling (not the same thing) than we are today. There is, she insists, “no linear history of improvement”, no golden age when everyone automatically sorted their household scraps and spent their evenings turning swords into ploughshares because they knew it was the right thing to do. Indeed, in the 1530s the more stuff you threw away, the better you were performing your civic duty: refuse and surfeit was built into the semiotics of display in Henry VIII’s England, which explains why, on formal occasions, it was stylish to have claret and white wine running down the gutters. Three generations later and Oliver Cromwell’s Parliamentarian troops had found new ways to manipulate codes of waste and value. In 1646 they ransacked Winchester cathedral and sent all the precious parchments off to London to be made into kites “withal to fly in the air”. Dickinson said her life had not been constrained or dreary in any way. “I find ecstasy in living,” she explained. The “mere sense of living is joy enough.” When at last the opportunity arose, Higginson posed the question he most wanted to ask: Did you ever want a job, have a desire to travel or see people? The question unleashed a forceful reply. “I never thought of conceiving that I could ever have the slightest approach to such a want in all future time.” Then she loaded on more. “I feel that I have not expressed myself strongly enough.” Dickinson reserved her most striking statement for what poetry meant to her, or, rather, how it made her feel. “If I read a book [and] it makes my whole body so cold no fire can ever warm me I know that is poetry,” she said. “If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry. These are the only way I know it. Is there any other way.” Dickinson was remarkable. Brilliant. Candid. Deliberate. Mystifying. After eight years of waiting, Higginson was finally sitting across from Emily Dickinson of Amherst, and all he wanted to do was listen.

Dickinson said her life had not been constrained or dreary in any way. “I find ecstasy in living,” she explained. The “mere sense of living is joy enough.” When at last the opportunity arose, Higginson posed the question he most wanted to ask: Did you ever want a job, have a desire to travel or see people? The question unleashed a forceful reply. “I never thought of conceiving that I could ever have the slightest approach to such a want in all future time.” Then she loaded on more. “I feel that I have not expressed myself strongly enough.” Dickinson reserved her most striking statement for what poetry meant to her, or, rather, how it made her feel. “If I read a book [and] it makes my whole body so cold no fire can ever warm me I know that is poetry,” she said. “If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry. These are the only way I know it. Is there any other way.” Dickinson was remarkable. Brilliant. Candid. Deliberate. Mystifying. After eight years of waiting, Higginson was finally sitting across from Emily Dickinson of Amherst, and all he wanted to do was listen. S. Jones and Stefan Helmreich in Boston Review (figure from From Kristine Moore et al., “

S. Jones and Stefan Helmreich in Boston Review (figure from From Kristine Moore et al., “ Aparna Kapadia in Scroll.in:

Aparna Kapadia in Scroll.in: Cate Lineberry over at Smithsonian Magazine:

Cate Lineberry over at Smithsonian Magazine:

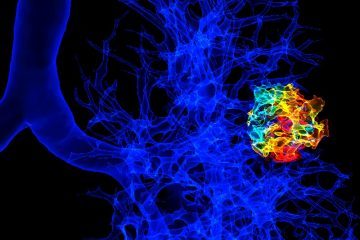

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the TRACERx project had recruited 760 people with early-stage lung cancer. After a person is diagnosed with a primary lung tumour, it is surgically removed and the cells are analysed to reconstruct the tumour’s evolutionary history. Each individual receives a computed tomography (CT) scan every year for five years to check whether their cancer has returned. If there is no sign of relapse, they are discharged and deemed to have been cured. People with later-stage tumours (stages 2 and 3) are offered chemotherapy following surgery to improve the chance of remission or cure.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the TRACERx project had recruited 760 people with early-stage lung cancer. After a person is diagnosed with a primary lung tumour, it is surgically removed and the cells are analysed to reconstruct the tumour’s evolutionary history. Each individual receives a computed tomography (CT) scan every year for five years to check whether their cancer has returned. If there is no sign of relapse, they are discharged and deemed to have been cured. People with later-stage tumours (stages 2 and 3) are offered chemotherapy following surgery to improve the chance of remission or cure.

When I was a child, my brother and I played a computer game based on the Indiana Jones movie franchise. In the course of his adventures, Indy would sometimes come to a delicate impasse that required tact and nuance to resolve. Some adversary was blocking his path to a relic or treasure (including, oddly enough, one of Plato’s lost dialogues), and he needed to say just the right thing to get past them and on to the next challenge. The game offered players a selection of five or so sentences to choose from. The world would sit there in 8-bit paralysis and wait while we pondered how to make it do what we wanted. Press enter on the right sentence and pixelated Indy would sail through. Choose something inapt and game over.

When I was a child, my brother and I played a computer game based on the Indiana Jones movie franchise. In the course of his adventures, Indy would sometimes come to a delicate impasse that required tact and nuance to resolve. Some adversary was blocking his path to a relic or treasure (including, oddly enough, one of Plato’s lost dialogues), and he needed to say just the right thing to get past them and on to the next challenge. The game offered players a selection of five or so sentences to choose from. The world would sit there in 8-bit paralysis and wait while we pondered how to make it do what we wanted. Press enter on the right sentence and pixelated Indy would sail through. Choose something inapt and game over. What they are understanding is that this coronavirus “has such a diversity of effects on so many different organs, it keeps us up at night,” said Thomas McGinn, deputy physician in chief at Northwell Health and director of the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research. “It’s amazing how many different ways it affects the body.”

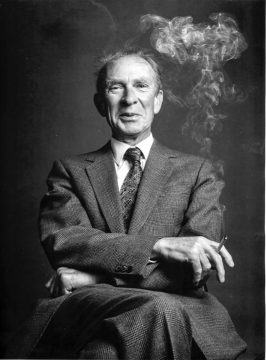

What they are understanding is that this coronavirus “has such a diversity of effects on so many different organs, it keeps us up at night,” said Thomas McGinn, deputy physician in chief at Northwell Health and director of the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research. “It’s amazing how many different ways it affects the body.” When I migrated from Cambridge to my new post at Pembroke College Oxford in the fall of 1969 I got the sense that many of the Old Guard there regarded me as some kind of foreign usurper. Perhaps their own favourite pupils had not been offered the job as they undoubtedly deserved. An exception was Peter Strawson, who was always friendly, and whom I came to admire greatly. Some years later when I belonged to a rather grubby photography workshop in the city I persuaded him to come downtown for me to make a portrait of him. I hope that some of the affection I felt comes through, as well as his undoubted amusement at the occasion.

When I migrated from Cambridge to my new post at Pembroke College Oxford in the fall of 1969 I got the sense that many of the Old Guard there regarded me as some kind of foreign usurper. Perhaps their own favourite pupils had not been offered the job as they undoubtedly deserved. An exception was Peter Strawson, who was always friendly, and whom I came to admire greatly. Some years later when I belonged to a rather grubby photography workshop in the city I persuaded him to come downtown for me to make a portrait of him. I hope that some of the affection I felt comes through, as well as his undoubted amusement at the occasion. In 1977, the poet Adrienne Rich exhorted a graduating class of young women to think of education

In 1977, the poet Adrienne Rich exhorted a graduating class of young women to think of education  Arising by most accounts in the last decades of the nineteenth century, the novel of ideas reflects the challenge posed by the integration of externally developed concepts long before the arrival of conceptual art. Although the novel’s verbal medium would seem to make it intrinsically suited to the endeavor, the mission of presenting “ideas” seems to have pushed a genre famous for its versatility toward a surprisingly limited repertoire of techniques. These came to obtrude against a set of generic expectations—nondidactic representation; a dynamic, temporally complex relation between events and the representation of events; character development; verisimilitude—established only in wake of the novel’s separation from history and romance at the start of the nineteenth century. Compared to these and even older, ancient genres like drama and lyric, the novel is astonishingly young, which is perhaps why departures from its still only freshly consolidated conventions seem especially noticeable.

Arising by most accounts in the last decades of the nineteenth century, the novel of ideas reflects the challenge posed by the integration of externally developed concepts long before the arrival of conceptual art. Although the novel’s verbal medium would seem to make it intrinsically suited to the endeavor, the mission of presenting “ideas” seems to have pushed a genre famous for its versatility toward a surprisingly limited repertoire of techniques. These came to obtrude against a set of generic expectations—nondidactic representation; a dynamic, temporally complex relation between events and the representation of events; character development; verisimilitude—established only in wake of the novel’s separation from history and romance at the start of the nineteenth century. Compared to these and even older, ancient genres like drama and lyric, the novel is astonishingly young, which is perhaps why departures from its still only freshly consolidated conventions seem especially noticeable.