Category: Recommended Reading

On José Ortega y Gasset

Morgan Sloan at Philosophy Now:

The impact of Germany on Ortega’s thoughts about his own country can be seen in his first major publication, Meditations on Quixote (1914), a book which, far from merely being a commentary on the famous Spanish novel, serves as a summary of Orteguian thought. Influenced by the biologist Jacob Von Uekull’s idea that a living organism must be studied within its environment in order to be understood, Ortega argued that human life must also be understood through its circumstances: “Circumstantial reality makes up the other half of me as a person: I need it to imagine myself and to be my true self,” he wrote. Social status, historical period, nationality, geographic location, and economic situation are all relevant when it comes to understanding how one sees the world and oneself, since they determine our perspective. This idea is summarized in Ortega’s most famous quote: ‘‘I am I and my circumstance, and if I do not save it, I do not save myself.’’ In just the same way that Ortega ventures out into the world down the Guadarrama river near his hometown, or that the Ancient Egyptians would have ventured out down the Nile, we also venture out into the world from our own places of origin. Regardless of how many new ideas you may open yourself to, and no matter how much they change your way of thinking, it will always be you perceiving them; your past experiences, your childhood, your economic and social status, your nationality, your historical period are vital in defining you as a person.

The impact of Germany on Ortega’s thoughts about his own country can be seen in his first major publication, Meditations on Quixote (1914), a book which, far from merely being a commentary on the famous Spanish novel, serves as a summary of Orteguian thought. Influenced by the biologist Jacob Von Uekull’s idea that a living organism must be studied within its environment in order to be understood, Ortega argued that human life must also be understood through its circumstances: “Circumstantial reality makes up the other half of me as a person: I need it to imagine myself and to be my true self,” he wrote. Social status, historical period, nationality, geographic location, and economic situation are all relevant when it comes to understanding how one sees the world and oneself, since they determine our perspective. This idea is summarized in Ortega’s most famous quote: ‘‘I am I and my circumstance, and if I do not save it, I do not save myself.’’ In just the same way that Ortega ventures out into the world down the Guadarrama river near his hometown, or that the Ancient Egyptians would have ventured out down the Nile, we also venture out into the world from our own places of origin. Regardless of how many new ideas you may open yourself to, and no matter how much they change your way of thinking, it will always be you perceiving them; your past experiences, your childhood, your economic and social status, your nationality, your historical period are vital in defining you as a person.

more here.

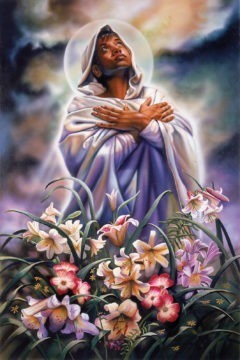

The Black Romantic

Jasmine Sanders at Artforum:

Their oeuvre comprises two categories, into which the bulk of Black Romantic art can also be slotted: “Home and Family Life” and “Religious and Spiritual Paintings.” The former is all nuclear bliss and filial piety—Mommy and Daddy dole out kisses and baths and lead the children in bedtime prayers. Little black girls come draped in the oversize uniforms of secretaries and teachers, the boys outfitted as preachers, lawyers, and athletes, all smiling a bit too wide and glowing the same glazed-honey-bun brown. The aforementioned Daniel belongs to the latter grouping, alongside other familiar biblical tableaux, the figures all recast as black and rendered with expressive detail. Christ, pressed hair agleam beneath the halo, shepherds his flock through thick Edenic brush. A personal favorite is Visitation, 1998, in which a white-robed girl gazes heavenward, the sky behind her a froth of crepuscular blues, greens, and plums. Her exposed neck imparts a devilish stroke of carnality welcome amid the otherwise pious scene. Likewise her glossed lips, which, along with her wispy bangs, situate her firmly in modernity, a Madonna-cum–round-the-way girl. Before her are lilies of all varieties and in all stages of bloom, their sharp, distinct oil lines contrasting with the gauzy, airbrushed sky. Smaller, yellow buds blossom throughout, a tonal invocation of the orisha Oshun, lover of honey, sensuality, and mayhem. The infusion of paganism and possibly Yoruba symbolism unyokes the portrait from its stodgy biblical origins and releases it into more rousing territory. Are we witnessing a visitation or a conjuring? Is hers the white robe of the Pentecost or the Priestess?

Their oeuvre comprises two categories, into which the bulk of Black Romantic art can also be slotted: “Home and Family Life” and “Religious and Spiritual Paintings.” The former is all nuclear bliss and filial piety—Mommy and Daddy dole out kisses and baths and lead the children in bedtime prayers. Little black girls come draped in the oversize uniforms of secretaries and teachers, the boys outfitted as preachers, lawyers, and athletes, all smiling a bit too wide and glowing the same glazed-honey-bun brown. The aforementioned Daniel belongs to the latter grouping, alongside other familiar biblical tableaux, the figures all recast as black and rendered with expressive detail. Christ, pressed hair agleam beneath the halo, shepherds his flock through thick Edenic brush. A personal favorite is Visitation, 1998, in which a white-robed girl gazes heavenward, the sky behind her a froth of crepuscular blues, greens, and plums. Her exposed neck imparts a devilish stroke of carnality welcome amid the otherwise pious scene. Likewise her glossed lips, which, along with her wispy bangs, situate her firmly in modernity, a Madonna-cum–round-the-way girl. Before her are lilies of all varieties and in all stages of bloom, their sharp, distinct oil lines contrasting with the gauzy, airbrushed sky. Smaller, yellow buds blossom throughout, a tonal invocation of the orisha Oshun, lover of honey, sensuality, and mayhem. The infusion of paganism and possibly Yoruba symbolism unyokes the portrait from its stodgy biblical origins and releases it into more rousing territory. Are we witnessing a visitation or a conjuring? Is hers the white robe of the Pentecost or the Priestess?

more here.

Just Hierarchy: Why Social Hierarchies Matter in China and the Rest of the World

Leanne Ogasawara in The New Rambler:

Imagine a drowning city. The collapse of the Greenland ice sheets has led to a ten-foot rise in global sea-levels. You think this is bad, but it is followed by further melting at the Aurora Basin in East Antarctica, resulting in another forty-foot rise. In his novel, New York 2140, Kim Stanley Robinson paints a picture of a flooded Manhattan, where morning commuters use vaporetti to travel to and from work and live in apartment towers that reach up out of the rising waters into the sky. As you might imagine, the city suffers from staggering income inequality. Hedge-fund millionaires weave in and out of shipping lanes in their private speedboats, as kids who can’t read ferry people around in leaky gondolas through waters poisoned with toxic waste. The world is facing an unprecedented existential threat. And survival will demand collective action and sacrifice. In such a world, what kind of government would you want calling the shots?

Imagine a drowning city. The collapse of the Greenland ice sheets has led to a ten-foot rise in global sea-levels. You think this is bad, but it is followed by further melting at the Aurora Basin in East Antarctica, resulting in another forty-foot rise. In his novel, New York 2140, Kim Stanley Robinson paints a picture of a flooded Manhattan, where morning commuters use vaporetti to travel to and from work and live in apartment towers that reach up out of the rising waters into the sky. As you might imagine, the city suffers from staggering income inequality. Hedge-fund millionaires weave in and out of shipping lanes in their private speedboats, as kids who can’t read ferry people around in leaky gondolas through waters poisoned with toxic waste. The world is facing an unprecedented existential threat. And survival will demand collective action and sacrifice. In such a world, what kind of government would you want calling the shots?

This question is not something only out of the world of fiction. Climate change and a worldwide pandemic are on everyone’s mind. Yet, for all the talk, it could be argued that intellectuals are not discussing enough what types of government might be best suited for making the tough decisions necessary for long-term planning and collective preparation. One notable exception to this is political philosopher Daniel Bell, who for the last two decades, has been writing books and a seemingly endless stream of provocative op-ed pieces highlighting the ways in which less-democratic forms of government might be better suited to tackling the tough issues we now face.

More here.

Medicine’s Machine Learning Problem

Rachel Thomas in the Boston Review:

Data science is remaking countless aspects of society, and medicine is no exception. The range of potential applications is already large and only growing by the day. Machine learning is now being used to determine which patients are at high risk of disease and need greater support (sometimes with racial bias), to discover which molecules may lead to promising new drugs, to search for cancer in X-rays (sometimes with gender bias), and to classify tissue on pathology slides. Last year MIT researchers trained an algorithm that was more accurate at predicting the presence of cancer within five years of a mammogram than techniques typically used in clinics, and a 2018 survey found that 84 percent of radiology clinics in the United States are using or plan to use machine learning software. The sense of excitement has been captured in popular books such as Eric Topol’s Deep Medicine: How Artificial Intelligence Can Make Healthcare Human Again (2019). But despite the promise of these data-based innovations, proponents often overlook the special risks of datafying medicine in the age of artificial intelligence.

Data science is remaking countless aspects of society, and medicine is no exception. The range of potential applications is already large and only growing by the day. Machine learning is now being used to determine which patients are at high risk of disease and need greater support (sometimes with racial bias), to discover which molecules may lead to promising new drugs, to search for cancer in X-rays (sometimes with gender bias), and to classify tissue on pathology slides. Last year MIT researchers trained an algorithm that was more accurate at predicting the presence of cancer within five years of a mammogram than techniques typically used in clinics, and a 2018 survey found that 84 percent of radiology clinics in the United States are using or plan to use machine learning software. The sense of excitement has been captured in popular books such as Eric Topol’s Deep Medicine: How Artificial Intelligence Can Make Healthcare Human Again (2019). But despite the promise of these data-based innovations, proponents often overlook the special risks of datafying medicine in the age of artificial intelligence.

Consider one striking example that has unfolded during the pandemic.

More here.

Michael Sandel, Grace Blakeley, Rory Stewart debate the case for ideological politics

Decades of research on risk perception can help us understand the Trump supporters who stormed the Capitol

Catherine Buni & Soraya Chemaly in Undark:

Although it is certainly true that Trump maintains a significant following among White women, his most fervent supporters tend to be White and male. Distributed across a wide swath of socioeconomic status, these men have unwaveringly — and even violently — supported the president, despite the historic risks his administration poses to public health, safety, and American democratic structures and ideals. No shortage of pundits and prognosticators have speculated about the factors underlying this support: Racism? The economy? Fragile masculinity? Class anxiety? Political fear? Sectarianism? In a New York Times op-ed last October, Michael Sokolove suggested that the political gulf between White men and just about everyone else should be dubbed “the White male gap” or “the White male problem.”

Although it is certainly true that Trump maintains a significant following among White women, his most fervent supporters tend to be White and male. Distributed across a wide swath of socioeconomic status, these men have unwaveringly — and even violently — supported the president, despite the historic risks his administration poses to public health, safety, and American democratic structures and ideals. No shortage of pundits and prognosticators have speculated about the factors underlying this support: Racism? The economy? Fragile masculinity? Class anxiety? Political fear? Sectarianism? In a New York Times op-ed last October, Michael Sokolove suggested that the political gulf between White men and just about everyone else should be dubbed “the White male gap” or “the White male problem.”

But cognitive scientists long ago coined a term for the psychological forces that have given rise to the gendered and racialized political divide that we’re seeing today. That research, and decades of subsequent scholarly work, suggest that if you want to understand the Trump phenomenon, you’d do well to first understand the science of risk perception.

More here.

Friday Poem

What the Burglar Left

The burglar left our apartment

much the same as before,

leaving two uncertain boot tracks

skidding downward from

the kicked-in window screen,

black roads leading nowhere,

thin plumes of smoking reaching up

through the white winter sky;

left the cats skittish but unharmed,

dishes filled, toys scattered;

left the kitchen drawers flung open,

closet doors ajar, the bed

pulled like a raft from its dock

in the corner, drifting;

left your favorite painting,

the books unread, music waiting

to be played; left your simple silver

rings and bracelets, those empty

perfume jars and baubles,

the gaudy brooch your grandmother

had given you many years before;

left the water drip-dripping

in the bathroom sink,

the silence we had collected

over the years, breath by breath;

left a presence that became,

with time, impossible to shake

or to name, this stranger walking

silently from room to room,

picking things up, turning them over,

wondering what might be

worth taking, what held value

and what did not, and not finding

much, moving along.

by Greg Watson

from Autumn Sky Poetry

Josh Hawley is the most dangerous man in America

Skylar Jordan in The Independent:

There is a photo of a Senator from Missouri — young and handsome, hair perfectly coiffed, suit beautifully tailored — which has circulated on social media since lawless rioters stormed the Capitol on Wednesday night. In it, the man in question raises a defiant fist in salute of the braying mob he is about to unleash upon the very heart of our Republic. It is a chilling image, one of a person with a clear lust for power. Donald Trump is our past, but this young man, already a powerful politician, could be our future.

There is a photo of a Senator from Missouri — young and handsome, hair perfectly coiffed, suit beautifully tailored — which has circulated on social media since lawless rioters stormed the Capitol on Wednesday night. In it, the man in question raises a defiant fist in salute of the braying mob he is about to unleash upon the very heart of our Republic. It is a chilling image, one of a person with a clear lust for power. Donald Trump is our past, but this young man, already a powerful politician, could be our future.

Josh Hawley is the most dangerous man in America. He was before the attempted coup. He certainly is now. Like Trump, he has wicked ideas. Unlike Trump, he is not stupid. He knows, surely, that this election was not stolen. He knows, surely, that there was no widespread voter fraud. He knows, surely, that the American people elected Joe Biden and Kamala Harris freely and fairly. He knows, surely, but it seems he does not care. This is a man who apparently cares only about his own political advancement. He ran for Missouri Attorney General in 2016, promising not to use it as a springboard to higher office. Then, he promptly ran for US Senate in 2018. Barely two years into his first term, he is now jockeying to be the anointed successor of Donald Trump, his eyes firmly fixated on 2024. This is why many believe he contested the results of the 2020 election in the first place. Presumably, it is why all of the Senators who objected did. The only nefarious plot to steal the election is their own, after all.

Some, when faced with an insurrection on their doorstep, had a change of heart. Just-defeated Senator Kelly Loeffler was one of them, saying in a speech from the floor of the Senate that the attempted coup which she supported not twelve hours before had “forced me to reconsider.” She went on to lament “the violence, the lawlessness, and siege of the halls of Congress.” While she didn’t disavow the very conspiracy theory which had prompted the violence and which she had peddled herself, at least she had the shame to pump the breaks as we neared the precipice of fascism.

More here.

Reality Is Plasticine

Eloghosa Osunde in The Paris Review:

My memory of my childhood is a black hole, save for the moments and ages marked by revelations and miracles. Take age six for instance, the year I learned to call things that are not (yet) as though they are (already.) It’s a biblical lesson, this, and my brothers were born from inside it, after years of waiting. Leaning on those words from the mouth of my mother, I prayed nightly for twin siblings, and soon started to talk about them like I knew them already. In a sense, I did. One, because they were real before their bodies were formed, and two, because my requests were already cool wax on the inside of God’s ear. I was taught things about holding hope unswervingly, about manifesting with laser focus, and the veracity of those lessons raised the hairs on the back of my neck even when there was no one there. I sealed prayers with amens and had them delivered swiftly; fleshed wishes out in my heart that stumbled into my life, already breathing. The pattern begins in my first name, directly translated to mean “it is not hard for God to do.” As in, nothing is. That name leads my head. My family took my dreams seriously, because God put the future behind my eyes often, but when the seeing got too heavy, I gave one of my many eyes back to God—the one that got visions, that put the weight of knowing on me—saying, This one is too much. Age thirteen, I believe, the year I learned that God understands consent, that They will never force anything on me for the sake of it.

The spiritual controls the physical, so everything breathes there before it ever lands here. I’ve never lost this lesson, which is also an inheritance, as in drooling through the genetic code. A gift, as in given freely. I did hide it though, so as not to look unhinged. For a long time, there was nothing I wanted more than to be normal, to be as a person should, to be young, to unknow things. It still takes work to release the weight of normal, of should.

More here.

Thursday, January 7, 2021

Work Sucks: On Anne Helen Petersen’s “Can’t Even”

Rithika Ramamurthy in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

In May of this year, The Washington Post published an article damningly titled “Millennials are the Unluckiest Generation in U.S. History.” The piece seemed to tell a truth that our cohort knows all too well: that the COVID-19 pandemic has brought not just an economic recession, but a regression. There were as many jobs in the spring of 2020 as there were in the fall of 1999. For those of us born between the years of 1981 and 1996, it is as if the post-crisis “growth” of the past 10 years never even happened.

In May of this year, The Washington Post published an article damningly titled “Millennials are the Unluckiest Generation in U.S. History.” The piece seemed to tell a truth that our cohort knows all too well: that the COVID-19 pandemic has brought not just an economic recession, but a regression. There were as many jobs in the spring of 2020 as there were in the fall of 1999. For those of us born between the years of 1981 and 1996, it is as if the post-crisis “growth” of the past 10 years never even happened.

In Can’t Even: How Millennials Became the Burnout Generation, Anne Helen Petersen explores the psychic dimensions of existing within this economic depression. According to Petersen, the main difference between millennials and the rest of the precariat is that we once had such great expectations. Molded in the mythos of meritocracy, our generation was raised to believe that we could beat bad circumstances and secure personal stability — if we simply worked hard enough. This happy ending has not materialized for most of us, and there has been extensive emotional fallout.

More here.

After the Pandemic: Hope and Breakthroughs for 2021

Ted Nordhaus and Alex Trembath at The Breakthrough Institute:

As the United States and much of the rest of the world struggles through a winter of intensifying death and disease, it is worth remembering that beyond the present darkness lies the dawn, as newly approved vaccines become widely available, and with that, perhaps, a return to something resembling normalcy.

As the United States and much of the rest of the world struggles through a winter of intensifying death and disease, it is worth remembering that beyond the present darkness lies the dawn, as newly approved vaccines become widely available, and with that, perhaps, a return to something resembling normalcy.

But even so, the post-vaccine world will also be changed in important ways — many for the better. The global biotech sector — a product of decades of public-private partnerships to develop superior medical technologies — appears to have produced effective vaccines in a remarkably short period of time using radically innovative technologies and immunity pathways. It will be the first-ever, broadly effective vaccine against a coronavirus of any sort, and hence, potentially opens the door to vaccinated immunity to a range of far more common maladies, from influenza to the common cold.

For this, among other reasons, the carnage that COVID-19 has wrought will not remotely rival pandemics past.

More here.

What We Still Get Wrong About Alexander Hamilton

Christian Parenti and Michael Busch in the Boston Review:

The Founding Fathers are a perennial source of both wisdom and controversy. Alexander Hamilton, the first U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, has taken pride of place in these public debates in recent years, thanks in part to Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical and Ron Chernow’s 2004 biography. In this interview, Michael Busch speaks with journalist and economist Christian Parenti about his new book Radical Hamilton: Economic Lessons from a Misunderstood Founder. They discuss how we still get Hamilton wrong and what we can learn from him about state building, economic planning, and the necessity of government action. —The Editors

The Founding Fathers are a perennial source of both wisdom and controversy. Alexander Hamilton, the first U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, has taken pride of place in these public debates in recent years, thanks in part to Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical and Ron Chernow’s 2004 biography. In this interview, Michael Busch speaks with journalist and economist Christian Parenti about his new book Radical Hamilton: Economic Lessons from a Misunderstood Founder. They discuss how we still get Hamilton wrong and what we can learn from him about state building, economic planning, and the necessity of government action. —The Editors

Michael Busch: You published Radical Hamilton in August with Verso Books. Let’s start at the beginning: Who was Alexander Hamilton? Why did you write this book?

Christian Parenti: Hamilton was a Revolutionary War soldier, advisor to George Washington, and major Federalist politician who played an important role in framing the U.S. Constitution and became the country’s first Secretary of the Treasury. He created the country’s modern financial system and central bank. Less commonly known, he also laid out a plan for government-led industrialization—that is to say, a plan for wholesale economic transformation.

I wrote the book by mistake, because I stumbled upon Hamilton’s often name-checked but rarely discussed magnum opus, his 1791 Report on the Subject of Manufactures. At first the plan was to just republish the Report with an introduction. But that grew into this book.

More here.

Stephen Asma on The Berwick Witches and King James

Between the sacred and the secular

Peter Gordon in New Spectator:

Marxism has had a long and troubled relationship with religion. In 1843 the young Karl Marx wrote in a critical essay on German philosophy that religion is “the opium of the people”, a phrase that would eventually harden into official atheism for the communist movement, though it poorly represented the true opinions of its founding theorist. After all, Marx also wrote that religion is “the sentiment of a heartless world” and “the soul of soul-less conditions”, as if to suggest that even the most fantastical beliefs bear within themselves a protest against worldly suffering and a promise to redeem us from conditions that might otherwise appear beyond all possible change. To call Marx a “secularist”, then, may be too simple. Marx saw religion as an illusion, but he was too much the dialectician to claim that it could be simply waved aside without granting that even illusions point darkly toward truth.

Marxism has had a long and troubled relationship with religion. In 1843 the young Karl Marx wrote in a critical essay on German philosophy that religion is “the opium of the people”, a phrase that would eventually harden into official atheism for the communist movement, though it poorly represented the true opinions of its founding theorist. After all, Marx also wrote that religion is “the sentiment of a heartless world” and “the soul of soul-less conditions”, as if to suggest that even the most fantastical beliefs bear within themselves a protest against worldly suffering and a promise to redeem us from conditions that might otherwise appear beyond all possible change. To call Marx a “secularist”, then, may be too simple. Marx saw religion as an illusion, but he was too much the dialectician to claim that it could be simply waved aside without granting that even illusions point darkly toward truth.

In the 20th century the story grew even more conflicted. While Soviet Marxism turned with a vengeance against religious believers and sought to dismantle religious institutions, some theorists in the West who saw in Marxism a resource for philosophical speculation felt that dialectics itself demanded a more nuanced understanding of religion, so that its energies could be harnessed for a task of redemption that was directed not to the heavens but to the Earth. Especially in Weimar Germany, Marxism and religion often came together into an explosive combination. Creative and heterodox thinkers such as Ernst Bloch fashioned speculative philosophies of history to show that the religious past contained untapped sources of messianic hope that kept alive the “spirit of utopia” for modern-day revolution. Anarchists such as Gustav Landauer, a leader of post-1918 socialist uprising who was murdered by the far-right in Bavaria, strayed from Marxism into an exotic syncretism of mystical and revolutionary thought.

More here.

Mass Delusion in America

Jeffrey Goldberg in The Atlantic:

Insurrection Day, 12:40 p.m.: A group of about 80 lumpen Trumpists were gathered outside the Commerce Department, near the White House. They organized themselves in a large circle, and stared at a boombox rigged to a megaphone. Their leader and, for some, savior—a number of them would profess to me their belief that the 45th president is an agent of God and his son, Jesus Christ—was rehearsing his pitiful list of grievances, and also fomenting a rebellion against, among others, the klatch of treacherous Republicans who had aligned themselves with the Constitution and against him. “A year from now we’re gonna start working on Congress,” Trump said through the boombox. “We gotta get rid of the weak congresspeople, the ones that aren’t any good, the Liz Cheneys of the world. We gotta get rid of them.” “Fuck Liz Cheney!” a man next to me yelled. He was bearded, and dressed in camouflage and Kevlar. His companion was dressed similarly, a valhalla: admit one patch sewn to his vest. Next to him was a woman wearing a full-body cat costume. “Fuck Liz Cheney!” she echoed. Catwoman, who would not tell me her name, carried a sign that read take off your mask smell the bullshit. Affixed to a corner of the sign was the letter Q.

Insurrection Day, 12:40 p.m.: A group of about 80 lumpen Trumpists were gathered outside the Commerce Department, near the White House. They organized themselves in a large circle, and stared at a boombox rigged to a megaphone. Their leader and, for some, savior—a number of them would profess to me their belief that the 45th president is an agent of God and his son, Jesus Christ—was rehearsing his pitiful list of grievances, and also fomenting a rebellion against, among others, the klatch of treacherous Republicans who had aligned themselves with the Constitution and against him. “A year from now we’re gonna start working on Congress,” Trump said through the boombox. “We gotta get rid of the weak congresspeople, the ones that aren’t any good, the Liz Cheneys of the world. We gotta get rid of them.” “Fuck Liz Cheney!” a man next to me yelled. He was bearded, and dressed in camouflage and Kevlar. His companion was dressed similarly, a valhalla: admit one patch sewn to his vest. Next to him was a woman wearing a full-body cat costume. “Fuck Liz Cheney!” she echoed. Catwoman, who would not tell me her name, carried a sign that read take off your mask smell the bullshit. Affixed to a corner of the sign was the letter Q.

“What’s your plan?” I asked her. People in the street, dozens at first, then hundreds, were moving past us, toward Pennsylvania Avenue, and then presumably on to the Capitol. “We’re going to stop the steal,” she answered. “If Pence isn’t going to stop it, we have to.” The treasonous behavior of Liz Cheney and many of her Republican colleagues was, to them, a fixed insurrectionary fact, but Pence was still in a plastic moment. Across the day, however, I could feel the Trump cult turning against him, as it turns against most everything.

More here.

Thursday Poem

Past is prologue —Anonymous

America

America I’ve given you all and now I’m nothing.

America two dollars and twentyseven cents January 17, 1956.

I can’t stand my own mind.

America when will we end the human war?

Go fuck yourself with your atom bomb.

I don’t feel good don’t bother me.

I won’t write my poem till I’m in my right mind.

America when will you be angelic?

When will you take off your clothes?

When will you look at yourself through the grave?

When will you be worthy of your million Trotskyites?

America why are your libraries full of tears?

America when will you send your eggs to India?

I’m sick of your insane demands.

When can I go into the supermarket and buy what I need with my good looks?

America after all it is you and I who are perfect not the next world.

Your machinery is too much for me.

You made me want to be a saint.

There must be some other way to settle this argument.

Burroughs is in Tangiers I don’t think he’ll come back it’s sinister.

Are you being sinister or is this some form of practical joke?

I’m trying to come to the point.

I refuse to give up my obsession.

America stop pushing I know what I’m doing.

America the plum blossoms are falling.

I haven’t read the newspapers for months, everyday somebody goes on trial for

…… murder.

America I feel sentimental about the Wobblies.

America I used to be a communist when I was a kid I’m not sorry.

I smoke marijuana every chance I get.

I sit in my house for days on end and stare at the roses in the closet.

When I go to Chinatown I get drunk and never get laid.

My mind is made up there’s going to be trouble.

You should have seen me reading Marx.

My psychoanalyst thinks I’m perfectly right.

I won’t say the Lord’s Prayer.

I have mystical visions and cosmic vibrations.

America I still haven’t told you what you did to Uncle Max after he came over from

…… Russia.

I’m addressing you.

Read more »

Slavoj Žižek – On G.W.F. Hegel

Colors / Tawny

Eileen Myles at Cabinet:

It’s interesting: there’s a wall along the freeway over there and there’s green dabs of paint every so often on it and a sun pouncing down. It feels kind of warm so the color isn’t right but there’s a feel. I’m thinking tawny isn’t a color. It’s a feeling. Like butter, the air in Hawaii, a feeling of value. Is anyone tawny who you can have. You know what I mean. It seems a slightly disdained object of lust. Her tawny skin—face it, used that way it’s a corrupt word. It isn’t even on the speaker. It’s on the spoken about. She or he is looking expensive and paid for. So I prefer to think about light. Open or closed. Closed is more literary light. Or light (there you go) of rooms you pass as you walk or drive by but most particularly I think as you ride by at night on a bike so you can smell the air out here and see the light in there, the light of a home you don’t know and feel mildly excited about, the light you’ll never know. Smokers with their backs to me standing in a sunset at the beach are closer to tawny than me.

It’s interesting: there’s a wall along the freeway over there and there’s green dabs of paint every so often on it and a sun pouncing down. It feels kind of warm so the color isn’t right but there’s a feel. I’m thinking tawny isn’t a color. It’s a feeling. Like butter, the air in Hawaii, a feeling of value. Is anyone tawny who you can have. You know what I mean. It seems a slightly disdained object of lust. Her tawny skin—face it, used that way it’s a corrupt word. It isn’t even on the speaker. It’s on the spoken about. She or he is looking expensive and paid for. So I prefer to think about light. Open or closed. Closed is more literary light. Or light (there you go) of rooms you pass as you walk or drive by but most particularly I think as you ride by at night on a bike so you can smell the air out here and see the light in there, the light of a home you don’t know and feel mildly excited about, the light you’ll never know. Smokers with their backs to me standing in a sunset at the beach are closer to tawny than me.

more here.

Too Nice to Be President

Tim Stanley at Literary Review:

This is the definitive Jimmy Carter anecdote. Once, when he was president, a bemused journalist asked if it was true that the leader of the free world was in charge of the schedule for the White House tennis court. Of course not, said Carter; don’t be silly. What he had done was tell staff they must speak to his secretary if they wanted to book a tennis session. That way, he elaborated, people cannot use the court simultaneously ‘unless they [are] either on opposite sides of the net or engaged in a doubles contest’.

This is the definitive Jimmy Carter anecdote. Once, when he was president, a bemused journalist asked if it was true that the leader of the free world was in charge of the schedule for the White House tennis court. Of course not, said Carter; don’t be silly. What he had done was tell staff they must speak to his secretary if they wanted to book a tennis session. That way, he elaborated, people cannot use the court simultaneously ‘unless they [are] either on opposite sides of the net or engaged in a doubles contest’.

Honest, wonky and utterly without humour, Carter was probably one of the smartest American presidents and, consequently, one of the worst. Two new accounts of his time in office bring clarity and depth to the record, albeit with varying degrees of sympathy.

more here.