Alejandro Chacoff in The New Yorker:

In 1973, shortly after his last novel, like the others before it, was rejected by publishers, the Italian writer Guido Morselli shot himself in the head and died. He left several rejection letters on his desk, and a short note that read, “I bear no grudges.” It was the kind of gesture one of his protagonists might have performed—a show of ironic detachment that belied a deep and obvious pain. Morselli was sixty years old. Before returning to his family’s home in Varese and ending his life, he had been living in near-isolation for two decades, on a small property in Lombardy, near the Swiss-Italian border. There he tended to the land, made wine, and wrote books that faced diminishing odds of publication. The last one that he finished tells the story of an apocalyptic event in which all of humanity suddenly vanishes, leaving a single man as the world’s only witness.

In 1973, shortly after his last novel, like the others before it, was rejected by publishers, the Italian writer Guido Morselli shot himself in the head and died. He left several rejection letters on his desk, and a short note that read, “I bear no grudges.” It was the kind of gesture one of his protagonists might have performed—a show of ironic detachment that belied a deep and obvious pain. Morselli was sixty years old. Before returning to his family’s home in Varese and ending his life, he had been living in near-isolation for two decades, on a small property in Lombardy, near the Swiss-Italian border. There he tended to the land, made wine, and wrote books that faced diminishing odds of publication. The last one that he finished tells the story of an apocalyptic event in which all of humanity suddenly vanishes, leaving a single man as the world’s only witness.

That book, “Dissipatio H.G.” (NYRB Classics), has now been published in English, in a translation by Frederika Randall, a journalist who turned to translating Italian after experiencing health problems caused by a fall. The plot begins with a botched suicide attempt: the unnamed narrator, a loner living in a retreat surrounded by meadows and glaciers, walks to a cave, on the eve of his fortieth birthday, intent on throwing himself down a well that leads to an underground lake. “Because the negative outweighed the positive,” he explains. “On my scales. By seventy percent. Was that a banal motive? I’m not sure.”

Sitting on the edge of the well, he doesn’t so much lose heart as get distracted. The mood is all wrong; he feels calm, lucid, too upbeat to go through with it. He is carrying a flashlight, which he flicks on and off. “Feet dangling in the dark,” he takes a sip of the brandy he has brought with him and considers how the Spanish variety is better than the French and why this is so widely unappreciated. Before leaving the cave, he bumps his head on a rock, and hears a peal of thunder: it’s the season’s first storm. Back home, lying in bed and still dressed, annoyed at the last-minute change of plans, he picks up a gun, considering an easier solution. He brings the “black-eyed girl” to his mouth and pulls the trigger, twice. The gun doesn’t work. He falls asleep.

More here.

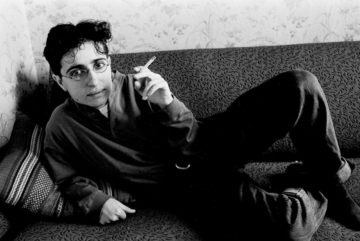

Born in 1940 in New York, Saul Kripke is one of the most influential philosophers of the 20th century, yet few outside philosophy have heard of him, let alone have any familiarity with his ideas. Still, Kripke’s arguments are often fairly easy to grasp. And, as I explain here, his conclusions challenge widely held philosophical assumptions – including assumptions about the role and limits of philosophy itself.

Born in 1940 in New York, Saul Kripke is one of the most influential philosophers of the 20th century, yet few outside philosophy have heard of him, let alone have any familiarity with his ideas. Still, Kripke’s arguments are often fairly easy to grasp. And, as I explain here, his conclusions challenge widely held philosophical assumptions – including assumptions about the role and limits of philosophy itself.

On a recent Saturday morning, my dad and I walked our dogs to the local basketball court to see what a persistent “thump-thump” noise coming from that direction was all about. Instead of basketball players, we found a fitness “boot camp,” where a gaggle of people in bright, tight clothing did squats and lunges and burpees in different stations, all to the same beat.

On a recent Saturday morning, my dad and I walked our dogs to the local basketball court to see what a persistent “thump-thump” noise coming from that direction was all about. Instead of basketball players, we found a fitness “boot camp,” where a gaggle of people in bright, tight clothing did squats and lunges and burpees in different stations, all to the same beat. The world needs more than Trump’s narrow transactional approach; so does the US. The only way forward is through true multilateralism, in which American exceptionalism is genuinely subordinated to common interests and values, international institutions, and a form of rule of law from which the US is not exempt. This would represent a major shift for the US, from a position of longstanding hegemony to one built on partnerships.

The world needs more than Trump’s narrow transactional approach; so does the US. The only way forward is through true multilateralism, in which American exceptionalism is genuinely subordinated to common interests and values, international institutions, and a form of rule of law from which the US is not exempt. This would represent a major shift for the US, from a position of longstanding hegemony to one built on partnerships. Celan’s gray language can be read as a subtle undermining of this principle of separation. Over the course of the four books collected in Memory Rose into Threshold Speech, there is a noticeable shift from a poetics of making-smooth to a poetics, as the color gray suggests, of entanglements, intertwinings, braids, weavings, mixtures. Although he once claimed that he did not believe in “bilingualism in poetry,” his poems have a distinctly international character, which is hardly surprising for a Romanian-born, German-speaking Jew working as a literary translator in Paris. (“International” was negatively connoted in the LTI and along with the adjective “global” it was frequently associated with Jews.) Many of his poems have foreign words as titles, or contain foreign words in them—French mostly, but also Hebrew, Yiddish, and Russian—each of which can be read as a “shibboleth” “cry[ing] out” in the “homeland’s alienness” (“Shibboleth”). The borders between identities and languages do not always lie between individual people or individual words; sometimes they lie within them. In his poems, Celan stands inside himself and the German language, “naming on the thresholds / what enters and leaves” (“Together”).

Celan’s gray language can be read as a subtle undermining of this principle of separation. Over the course of the four books collected in Memory Rose into Threshold Speech, there is a noticeable shift from a poetics of making-smooth to a poetics, as the color gray suggests, of entanglements, intertwinings, braids, weavings, mixtures. Although he once claimed that he did not believe in “bilingualism in poetry,” his poems have a distinctly international character, which is hardly surprising for a Romanian-born, German-speaking Jew working as a literary translator in Paris. (“International” was negatively connoted in the LTI and along with the adjective “global” it was frequently associated with Jews.) Many of his poems have foreign words as titles, or contain foreign words in them—French mostly, but also Hebrew, Yiddish, and Russian—each of which can be read as a “shibboleth” “cry[ing] out” in the “homeland’s alienness” (“Shibboleth”). The borders between identities and languages do not always lie between individual people or individual words; sometimes they lie within them. In his poems, Celan stands inside himself and the German language, “naming on the thresholds / what enters and leaves” (“Together”).

Covid-19 was the big issue of 2020, there is no question about that. But I’m hoping that, by the end of 2021, the vaccines will have kicked in and we’ll be talking more about climate than the coronavirus. 2021 will certainly be a crunch year for tackling climate change. Antonio Guterres, the UN Secretary General, told me he thinks it is a “make or break” moment for the issue. So, in the spirit of New Year’s optimism, here’s why I believe 2021 could confound the doomsters and see a breakthrough in global ambition on climate.

Covid-19 was the big issue of 2020, there is no question about that. But I’m hoping that, by the end of 2021, the vaccines will have kicked in and we’ll be talking more about climate than the coronavirus. 2021 will certainly be a crunch year for tackling climate change. Antonio Guterres, the UN Secretary General, told me he thinks it is a “make or break” moment for the issue. So, in the spirit of New Year’s optimism, here’s why I believe 2021 could confound the doomsters and see a breakthrough in global ambition on climate. In 1973, shortly after his last novel, like the others before it, was rejected by publishers, the Italian writer Guido Morselli shot himself in the head and died. He left several rejection letters on his desk, and a short note that read, “I bear no grudges.” It was the kind of gesture one of his protagonists might have performed—a show of ironic detachment that belied a deep and obvious pain. Morselli was sixty years old. Before returning to his family’s home in Varese and ending his life, he had been living in near-isolation for two decades, on a small property in Lombardy, near the Swiss-Italian border. There he tended to the land, made wine, and wrote books that faced diminishing odds of publication. The last one that he finished tells the story of an apocalyptic event in which all of humanity suddenly vanishes, leaving a single man as the world’s only witness.

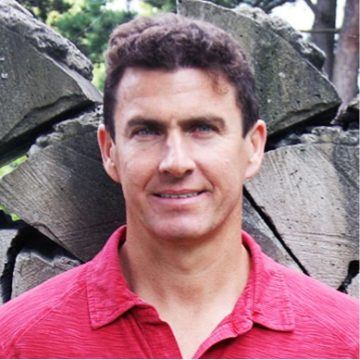

In 1973, shortly after his last novel, like the others before it, was rejected by publishers, the Italian writer Guido Morselli shot himself in the head and died. He left several rejection letters on his desk, and a short note that read, “I bear no grudges.” It was the kind of gesture one of his protagonists might have performed—a show of ironic detachment that belied a deep and obvious pain. Morselli was sixty years old. Before returning to his family’s home in Varese and ending his life, he had been living in near-isolation for two decades, on a small property in Lombardy, near the Swiss-Italian border. There he tended to the land, made wine, and wrote books that faced diminishing odds of publication. The last one that he finished tells the story of an apocalyptic event in which all of humanity suddenly vanishes, leaving a single man as the world’s only witness. AB: Yes, indeed! I was there when Christof Koch, a cognitive neuroscientist of international renown, said that philosophers had made a good speculative start but scientists (he meant ‘we scientists’) are now doing the job properly. A view that betrays a deep-running ignorance of philosophy, in my opinion. Philosophy has a central role to play in cognitive science and philosophy of cognitive science still has a lot of work to do. In cognitive science, philosophers do vital work clarifying concepts (the conceptual toolbox of cognitive research is a mess) and showing how hypotheses and theories relate to one another – in short, showing how things, in the broadest sense of ‘things’, hang together, in the broadest sense of ‘hang together’, as the outstanding American philosopher Wilfred Sellars put it some decades ago. Philosophy of cognitive science is just a branch of philosophy of science, though the wide range of styles of explanation used by cognitive researchers, just to take one example, offer some special challenges.

AB: Yes, indeed! I was there when Christof Koch, a cognitive neuroscientist of international renown, said that philosophers had made a good speculative start but scientists (he meant ‘we scientists’) are now doing the job properly. A view that betrays a deep-running ignorance of philosophy, in my opinion. Philosophy has a central role to play in cognitive science and philosophy of cognitive science still has a lot of work to do. In cognitive science, philosophers do vital work clarifying concepts (the conceptual toolbox of cognitive research is a mess) and showing how hypotheses and theories relate to one another – in short, showing how things, in the broadest sense of ‘things’, hang together, in the broadest sense of ‘hang together’, as the outstanding American philosopher Wilfred Sellars put it some decades ago. Philosophy of cognitive science is just a branch of philosophy of science, though the wide range of styles of explanation used by cognitive researchers, just to take one example, offer some special challenges. We all know stereotypes about people from different countries; but we also recognize that there really are broad cultural differences between people who grow up in different societies. This raises a challenge when most psychological research is performed on a narrow and unrepresentative slice of the world’s population — a subset that has accurately been labeled as

We all know stereotypes about people from different countries; but we also recognize that there really are broad cultural differences between people who grow up in different societies. This raises a challenge when most psychological research is performed on a narrow and unrepresentative slice of the world’s population — a subset that has accurately been labeled as  We used to think, with good reason, that globalization had defanged national governments. Presidents cowered before the bond markets. Prime ministers ignored their country’s poor but never Standard & Poor’s. Finance ministers behaved like Goldman Sachs’s knaves and the International Monetary Fund’s satraps. Media moguls, oil men, and financiers, no less than left-wing critics of globalized capitalism, agreed that governments were no longer in control.

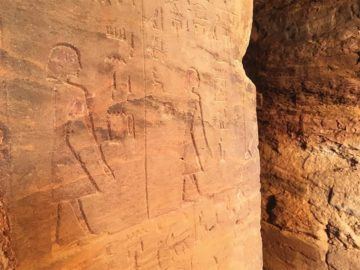

We used to think, with good reason, that globalization had defanged national governments. Presidents cowered before the bond markets. Prime ministers ignored their country’s poor but never Standard & Poor’s. Finance ministers behaved like Goldman Sachs’s knaves and the International Monetary Fund’s satraps. Media moguls, oil men, and financiers, no less than left-wing critics of globalized capitalism, agreed that governments were no longer in control. Centuries before Moses wandered in the “great and terrible wilderness” of the Sinai Peninsula, this triangle of desert wedged between Africa and Asia attracted speculators, drawn by rich mineral deposits hidden in the rocks. And it was on one of these expeditions, around 4,000 years ago, that some mysterious person or group took a bold step that, in retrospect, was truly revolutionary. Scratched on the wall of a mine is the very first attempt at something we use every day: the alphabet.

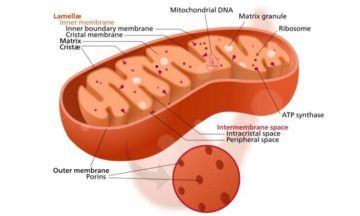

Centuries before Moses wandered in the “great and terrible wilderness” of the Sinai Peninsula, this triangle of desert wedged between Africa and Asia attracted speculators, drawn by rich mineral deposits hidden in the rocks. And it was on one of these expeditions, around 4,000 years ago, that some mysterious person or group took a bold step that, in retrospect, was truly revolutionary. Scratched on the wall of a mine is the very first attempt at something we use every day: the alphabet. Insofar as variants for mitochondrial disease are supposed to be rare in the genome, don’t think for even a minute that it can’t happen to you. In fact, the closer one looks at the full mitonuclear genomes of normal folks, the more one realizes that no one is actually normal—we are all, shall we say, temporarily asymptomatic. But in the fullness of time, many asymptomatics develop the hallmarks of

Insofar as variants for mitochondrial disease are supposed to be rare in the genome, don’t think for even a minute that it can’t happen to you. In fact, the closer one looks at the full mitonuclear genomes of normal folks, the more one realizes that no one is actually normal—we are all, shall we say, temporarily asymptomatic. But in the fullness of time, many asymptomatics develop the hallmarks of  The first thing I noticed about Le Cirque when I saw it at Pace was its clumsiness. The sculpture is comically, endearingly big: thirteen feet tall and almost a hundred feet in circumference, with elephant legs and zebra stripes like scribbles blown up a thousandfold. Since it didn’t have to compete for attention (the only other work in the exhibition was a 1968 maquette of Dubuffet’s equally sprawling Jardin d’émail), it seemed even bigger. As you walk through it, Le Cirque suggests the organic and the architectural all at once, as though the big top has somehow merged with the animals. For all its maker’s prestige, there’s still a whiff of third-grade daffiness in the air—I suppose there are higher compliments for the father of Art Brut, but I’m not sure what they’d be.

The first thing I noticed about Le Cirque when I saw it at Pace was its clumsiness. The sculpture is comically, endearingly big: thirteen feet tall and almost a hundred feet in circumference, with elephant legs and zebra stripes like scribbles blown up a thousandfold. Since it didn’t have to compete for attention (the only other work in the exhibition was a 1968 maquette of Dubuffet’s equally sprawling Jardin d’émail), it seemed even bigger. As you walk through it, Le Cirque suggests the organic and the architectural all at once, as though the big top has somehow merged with the animals. For all its maker’s prestige, there’s still a whiff of third-grade daffiness in the air—I suppose there are higher compliments for the father of Art Brut, but I’m not sure what they’d be. In the final days of the Second World War, a train loaded with relics of the collapsing Third Reich was speeding toward the Czech border when American pilots, flying P-47 fighters, spotted it and opened fire. The train ground to a halt in a forest, where German soldiers spirited the cargo away. They were pursued, not long afterward, by Gordon Gilkey, a young captain from Linn County, Oregon, who had been ordered to gather up all the Nazi propaganda and military art he could find. Gilkey tracked the smugglers to an abandoned woodcutter’s hut, where he pried up the floorboards and found what he was looking for: a collection of drawings and watercolors belonging to the German military’s high command. The cache had survived the strafing, only to be afflicted by mildew and a family of hungry mice. “They had eaten the ends off many pictures, large holes in a few, and gave all the cabin pictures an uneven deckle edge,” Gilkey wrote.

In the final days of the Second World War, a train loaded with relics of the collapsing Third Reich was speeding toward the Czech border when American pilots, flying P-47 fighters, spotted it and opened fire. The train ground to a halt in a forest, where German soldiers spirited the cargo away. They were pursued, not long afterward, by Gordon Gilkey, a young captain from Linn County, Oregon, who had been ordered to gather up all the Nazi propaganda and military art he could find. Gilkey tracked the smugglers to an abandoned woodcutter’s hut, where he pried up the floorboards and found what he was looking for: a collection of drawings and watercolors belonging to the German military’s high command. The cache had survived the strafing, only to be afflicted by mildew and a family of hungry mice. “They had eaten the ends off many pictures, large holes in a few, and gave all the cabin pictures an uneven deckle edge,” Gilkey wrote.