Justin E. H. Smith in his Substack Newsletter:

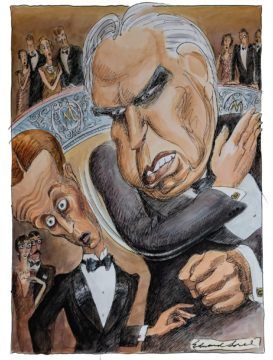

Although the literary theorist and anthropologist René Girard has many Silicon Valley disciples, surely the most notable of them is the German-born venture capitalist and founder of PayPal, Peter Thiel. A student of Girard’s while at Stanford in the late 1980s, Thiel would go on to report, in several interviews, and somewhat more sub-rosa in his 2014 book, From Zero to One, that Girard is his greatest intellectual inspiration. He is in the habit of recommending Girard’s Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World (1978) to others in the tech industry.

Although the literary theorist and anthropologist René Girard has many Silicon Valley disciples, surely the most notable of them is the German-born venture capitalist and founder of PayPal, Peter Thiel. A student of Girard’s while at Stanford in the late 1980s, Thiel would go on to report, in several interviews, and somewhat more sub-rosa in his 2014 book, From Zero to One, that Girard is his greatest intellectual inspiration. He is in the habit of recommending Girard’s Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World (1978) to others in the tech industry.

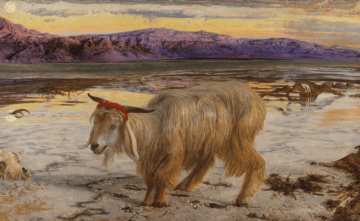

Girard has two big ideas, each intertwined with the other: the theory of mimesis, and the theory of the scapegoat. Michel Serres, another French theorist long resident at Stanford, and a strong advocate for Girard’s ideas, has described Girard as the “Darwin of the human sciences”, and has identified the mimetic theory as the relevant analog in the humanities of the Darwinian theory of natural selection.

For Girard, everything is imitation. Or rather, every human action that rises above “merely” biological appetite and that is experienced as desire for a given object, in fact is not a desire for that object itself, but a desire to have the object that somebody else already has.

More here.

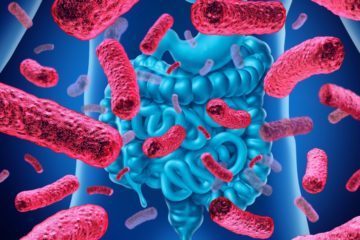

We are never alone. And by this statement, I do not intend to argue for existence of some supernatural entities, aliens or God. We are never alone because we all share our bodies with trillions of symbiotic microorganisms that perform various physiological functions crucial for our health. In fact, they may be responsible for even more than that. Here, I present a view that the symbiotic microbiota is an important part of the complex system constituting our consciousness. By consciousness, I mean the type called phenomenal consciousness (Block 2002) which stands for the subjective experience of what is it like to be someone (see Nagel 1974).

We are never alone. And by this statement, I do not intend to argue for existence of some supernatural entities, aliens or God. We are never alone because we all share our bodies with trillions of symbiotic microorganisms that perform various physiological functions crucial for our health. In fact, they may be responsible for even more than that. Here, I present a view that the symbiotic microbiota is an important part of the complex system constituting our consciousness. By consciousness, I mean the type called phenomenal consciousness (Block 2002) which stands for the subjective experience of what is it like to be someone (see Nagel 1974). When we speak to our sisters and brothers living in poverty in the United States, the confessional trope that describes so many dysfunctional relationships should be our opening line. “Poverty is a choice that the fortunate collectively make,” social worker Joanne Goldblum and journalist Colleen Shaddox write in

When we speak to our sisters and brothers living in poverty in the United States, the confessional trope that describes so many dysfunctional relationships should be our opening line. “Poverty is a choice that the fortunate collectively make,” social worker Joanne Goldblum and journalist Colleen Shaddox write in  The investigative journalist Gary Taubes is known for his painstakingly researched and withering demolitions of the “eat less, move more” diet orthodoxy, but his latest book is personal. The Case for Keto is aimed at “those of us who fatten easily”. Taubes locates himself in this beleaguered group, “despite an addiction to exercise for the better part of a decade” and a diet of “low-fat, mostly plant ‘healthy’ eating”. “I avoided avocados and peanut butter because they were high in fat and I thought of red meat, particularly steak and bacon, as an agent of premature death. I ate only the whites of egg.” Yet still he remained overweight.

The investigative journalist Gary Taubes is known for his painstakingly researched and withering demolitions of the “eat less, move more” diet orthodoxy, but his latest book is personal. The Case for Keto is aimed at “those of us who fatten easily”. Taubes locates himself in this beleaguered group, “despite an addiction to exercise for the better part of a decade” and a diet of “low-fat, mostly plant ‘healthy’ eating”. “I avoided avocados and peanut butter because they were high in fat and I thought of red meat, particularly steak and bacon, as an agent of premature death. I ate only the whites of egg.” Yet still he remained overweight. Both grew up in the Midwest, both wrote novels that skewered the patriarchal, conformist towns where they were raised, and both shared the distinction of having churchmen condemn their books as “immoral.” They should have been friends, but by 1925, when Theodore Dreiser’s “An American Tragedy” was published, he and Sinclair Lewis were hoping to become the first American to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. Lewis had already produced “Main Street” in 1920, then followed it with “Babbitt,” “Arrowsmith,” “Elmer Gantry” and “Dodsworth” before the decade was even over. In 1930 the prize was his.

Both grew up in the Midwest, both wrote novels that skewered the patriarchal, conformist towns where they were raised, and both shared the distinction of having churchmen condemn their books as “immoral.” They should have been friends, but by 1925, when Theodore Dreiser’s “An American Tragedy” was published, he and Sinclair Lewis were hoping to become the first American to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. Lewis had already produced “Main Street” in 1920, then followed it with “Babbitt,” “Arrowsmith,” “Elmer Gantry” and “Dodsworth” before the decade was even over. In 1930 the prize was his. Priya Satia in Aeon:

Priya Satia in Aeon: Peter Gordon in The New Statesman:

Peter Gordon in The New Statesman:

Christopher Mackin and Richard May in The New Republic:

Christopher Mackin and Richard May in The New Republic: On the face of it, “Feline Philosophy” would seem like a departure for Gray — a playful exploration of what cats might have to teach humans in our never-ending quest to understand ourselves. But the book, in true Gray fashion, suggests that this very quest may itself be doomed. “Consciousness,” he writes, “has been overrated.” We get worried, anxious and miserable. Our vaunted capacity for abstract thought often gets us (or others) into trouble. We may be the only species to pursue scientific inquiry, but we’re also the only species that has consciously perpetrated genocides. Cats, unlike humans, don’t trick themselves into believing they are saviors, wreaking havoc in the process. “When cats are not hunting or mating, eating or playing, they sleep,” Gray writes. “There is no inner anguish that forces them into constant activity.”

On the face of it, “Feline Philosophy” would seem like a departure for Gray — a playful exploration of what cats might have to teach humans in our never-ending quest to understand ourselves. But the book, in true Gray fashion, suggests that this very quest may itself be doomed. “Consciousness,” he writes, “has been overrated.” We get worried, anxious and miserable. Our vaunted capacity for abstract thought often gets us (or others) into trouble. We may be the only species to pursue scientific inquiry, but we’re also the only species that has consciously perpetrated genocides. Cats, unlike humans, don’t trick themselves into believing they are saviors, wreaking havoc in the process. “When cats are not hunting or mating, eating or playing, they sleep,” Gray writes. “There is no inner anguish that forces them into constant activity.” Though wood still plays an important role in the construction of our homes — think two-by-four stud supports and plywood in walls, flooring and roofing — our eye most often falls on exteriors covered in synthetic materials like vinyl siding. Some playgrounds that once featured lots of wood now have our kids screaming atop molded plastic play sets. And thousands of readers will take in this review on a digital device, not on a sheet of paper made from dried wood pulp. In a world where wood is, if not absent, increasingly out of sight, British biologist Roland Ennos suggests we may not be paying enough attention to its importance. He contends that wood is not merely useful but central to human history. “It is the one material,” Ennos writes in “

Though wood still plays an important role in the construction of our homes — think two-by-four stud supports and plywood in walls, flooring and roofing — our eye most often falls on exteriors covered in synthetic materials like vinyl siding. Some playgrounds that once featured lots of wood now have our kids screaming atop molded plastic play sets. And thousands of readers will take in this review on a digital device, not on a sheet of paper made from dried wood pulp. In a world where wood is, if not absent, increasingly out of sight, British biologist Roland Ennos suggests we may not be paying enough attention to its importance. He contends that wood is not merely useful but central to human history. “It is the one material,” Ennos writes in “ The COVID-19 pandemic and recession caused devastating long-term unemployment and income losses for many, historic low interest rates for borrowers, and stock market highs for investors. Since NextAdvisor’s launch in June, we’ve followed along, looking to the experts and Americans directly affected to better understand — and share — how it all impacts your wallet. As we say goodbye to 2020, our writers and editors are reflecting on what we learned, and want to share some new practices we’re bringing into the new year. The coronavirus pandemic hit the United States in early March, resulting in millions of jobs lost, shuttered businesses, and deep uncertainty about the future. At its peak in April, the unemployment rate reached 14.7%. Today,

The COVID-19 pandemic and recession caused devastating long-term unemployment and income losses for many, historic low interest rates for borrowers, and stock market highs for investors. Since NextAdvisor’s launch in June, we’ve followed along, looking to the experts and Americans directly affected to better understand — and share — how it all impacts your wallet. As we say goodbye to 2020, our writers and editors are reflecting on what we learned, and want to share some new practices we’re bringing into the new year. The coronavirus pandemic hit the United States in early March, resulting in millions of jobs lost, shuttered businesses, and deep uncertainty about the future. At its peak in April, the unemployment rate reached 14.7%. Today,  “The Over-Soul” is my favorite essay, but Emerson is better known for “Self Reliance,” that famous paean to individualism. This is the one where Emerson declares that “[w]hoso would be a man must be nonconformist,” and disdains society as “a join-stock company, in which the members agree, for the better securing of his bread to each shareholder, to surrender the liberty and culture of the eater.” Again, the writing is seductive. For anyone adrift in the world, it is reassuring to hear that “[n]othing can bring you peace but yourself,” or that mental will can triumph over fate. It can really be this simple: “In the Will work and acquire, and thou hast chained the wheel of Chance, and shalt sit hereafter out of fear from her rotations.”

“The Over-Soul” is my favorite essay, but Emerson is better known for “Self Reliance,” that famous paean to individualism. This is the one where Emerson declares that “[w]hoso would be a man must be nonconformist,” and disdains society as “a join-stock company, in which the members agree, for the better securing of his bread to each shareholder, to surrender the liberty and culture of the eater.” Again, the writing is seductive. For anyone adrift in the world, it is reassuring to hear that “[n]othing can bring you peace but yourself,” or that mental will can triumph over fate. It can really be this simple: “In the Will work and acquire, and thou hast chained the wheel of Chance, and shalt sit hereafter out of fear from her rotations.”