Hugh Aldersey-Williams in Aeon:

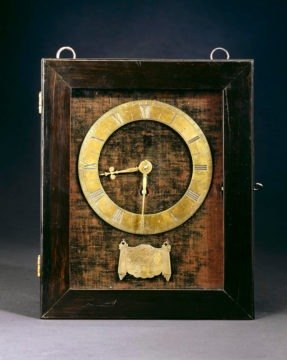

During the 1650s, the admired Dutch diplomat Constantijn Huygens often found himself with time on his hands. He was the loyal secretary to successive princes in the House of Orange, the ruling dynasty in the northern Netherlands during the Eighty Years’ War with Spain, and had been knighted by both James I of England and Louis XIII of France. Now that the Dutch were embarking upon an experimental period of republican government, his diplomatic services were no longer required. So he set down his untiring pen, and turned to books.

During the 1650s, the admired Dutch diplomat Constantijn Huygens often found himself with time on his hands. He was the loyal secretary to successive princes in the House of Orange, the ruling dynasty in the northern Netherlands during the Eighty Years’ War with Spain, and had been knighted by both James I of England and Louis XIII of France. Now that the Dutch were embarking upon an experimental period of republican government, his diplomatic services were no longer required. So he set down his untiring pen, and turned to books.

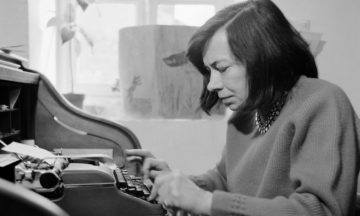

In September 1653, he happened to read Poems and Fancies, a newly published collection by the English exile Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle, a staunch royalist who had sought to escape the persecutions of Oliver Cromwell’s Commonwealth by making her home in the city of Antwerp. Among its verses and dialogues, Cavendish’s book featured a range of her untested scientific ideas, including a 50-page verse exposition of her atomic theory. Her ‘extravagant atoms kept me from sleeping a great part of last night,’ Huygens wrote to a mutual friend.

A few years later, in March 1657, the 60-year-old Huygens initiated a correspondence with Cavendish, wondering if she might have an explanation for an odd phenomenon that had given rise to something of a craze in the salons of Europe. So-called Prince Rupert’s drops were comma-shaped beads formed by trickling molten glass into a bucket of cold water.

More here.

The storming of the US Capitol on January 6 is easily misunderstood. Shaken by the ordeal, members of Congress have issued statements explaining that America is a nation of laws, not mobs. The implication is that the disruption incited by President Donald Trump is something new. It is not. The United States has a long history of mob violence stoked by white politicians in the service of rich white Americans. What was unusual this time is that the white mob turned on the white politicians, rather than the people of color who are usually the victims.

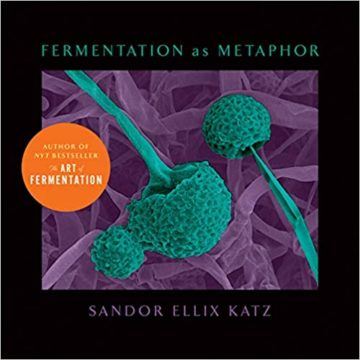

The storming of the US Capitol on January 6 is easily misunderstood. Shaken by the ordeal, members of Congress have issued statements explaining that America is a nation of laws, not mobs. The implication is that the disruption incited by President Donald Trump is something new. It is not. The United States has a long history of mob violence stoked by white politicians in the service of rich white Americans. What was unusual this time is that the white mob turned on the white politicians, rather than the people of color who are usually the victims. He calls himself a fermentation revivalist. With several award-winning books on the subject and a very large following on YouTube, Sandor Ellix Katz is part fermentation expert and part fermentation superstar. But I wondered: why revivalist? Did fermentation ever go out of fashion? Where I spent my adult life ‑ in Japan ‑ fermentation has always stood centre-stage. From soy sauce to miso and from sake to tsukemono, it is hard to imagine Japanese food without it.

He calls himself a fermentation revivalist. With several award-winning books on the subject and a very large following on YouTube, Sandor Ellix Katz is part fermentation expert and part fermentation superstar. But I wondered: why revivalist? Did fermentation ever go out of fashion? Where I spent my adult life ‑ in Japan ‑ fermentation has always stood centre-stage. From soy sauce to miso and from sake to tsukemono, it is hard to imagine Japanese food without it. It was, in all respects, another typical Covid evening. We’d finished our regulation bottle of Chianti, yet again postponed our online Italian lesson, and decided that not one of the films on television merited a moment of our time. Three vacant hours lay between us and bedtime.

It was, in all respects, another typical Covid evening. We’d finished our regulation bottle of Chianti, yet again postponed our online Italian lesson, and decided that not one of the films on television merited a moment of our time. Three vacant hours lay between us and bedtime. A kinder fate might have cast Donald J Trump as a maitre d’ in the world of swank, careful to save the best tables for his best customers, warmly responsive to a good tip, the ultimate outsider as insider, being and also impersonating a man whose fondest memory of youth is the first time he heard “I Did It My Way.” But fate was not kind. It made him a billionaire of sorts with a trick of putting his name on vodka bottles and casinos, of growing richer through bankruptcies and bad debt, of enthralling the tabloids. And yet, despite all this, Manhattan seems to have remained unimpressed. A tower almost as tall as he said it was, remarkable hair, and yet he was the baffled outsider trying to figure out what he was getting wrong. What began as farce is ending as tragedy.

A kinder fate might have cast Donald J Trump as a maitre d’ in the world of swank, careful to save the best tables for his best customers, warmly responsive to a good tip, the ultimate outsider as insider, being and also impersonating a man whose fondest memory of youth is the first time he heard “I Did It My Way.” But fate was not kind. It made him a billionaire of sorts with a trick of putting his name on vodka bottles and casinos, of growing richer through bankruptcies and bad debt, of enthralling the tabloids. And yet, despite all this, Manhattan seems to have remained unimpressed. A tower almost as tall as he said it was, remarkable hair, and yet he was the baffled outsider trying to figure out what he was getting wrong. What began as farce is ending as tragedy. Adam Shatz in the LRB:

Adam Shatz in the LRB:

Jonathan Kramnick in Critical Inquiry:

Jonathan Kramnick in Critical Inquiry: Liza Featherstone in JSTOR Daily:

Liza Featherstone in JSTOR Daily: Mike Davis in the NLR’s Sidecar:

Mike Davis in the NLR’s Sidecar: T

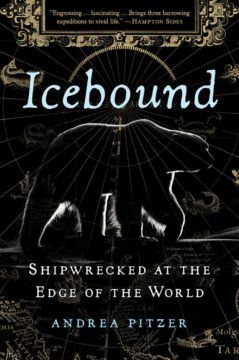

T Stories of Arctic expeditions continue to fascinate us because they expose humanity in extremis — people pushed to their best and worst by hypothermia, hunger and despair. Sir John Franklin’s 1845 Arctic expedition to find a northwest passage became the shame of Britain when it was discovered that his men, trapped for months in Canada, resorted to cannibalism. Ernest Shackleton is a hero for rescuing all but three of his crew in Antarctica after his ship, the Endurance, was lost.

Stories of Arctic expeditions continue to fascinate us because they expose humanity in extremis — people pushed to their best and worst by hypothermia, hunger and despair. Sir John Franklin’s 1845 Arctic expedition to find a northwest passage became the shame of Britain when it was discovered that his men, trapped for months in Canada, resorted to cannibalism. Ernest Shackleton is a hero for rescuing all but three of his crew in Antarctica after his ship, the Endurance, was lost. At noon, one hour before the two chambers met in joint session, President Trump took the stage before a crowd not far from 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. There he whipped up the faithful, men and women he had fed and fattened with stories of election fraud and voting dumps, to march on the Capitol and protest outside. The crowd cheered him on, considering themselves to be real (and armed) patriots there to save America at the “Save America rally.”

At noon, one hour before the two chambers met in joint session, President Trump took the stage before a crowd not far from 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. There he whipped up the faithful, men and women he had fed and fattened with stories of election fraud and voting dumps, to march on the Capitol and protest outside. The crowd cheered him on, considering themselves to be real (and armed) patriots there to save America at the “Save America rally.” On Wednesday afternoon, as insurrectionists assaulted the Capitol, a man wearing a brown vest over a black sweatshirt walked through the halls of Congress with the Confederate battle flag hanging over his shoulder. One widely circulated photo, taken by Mike Theiler of Reuters, captured him mid-stride, part of the flag almost glowing with the light coming from the hallway to his left.

On Wednesday afternoon, as insurrectionists assaulted the Capitol, a man wearing a brown vest over a black sweatshirt walked through the halls of Congress with the Confederate battle flag hanging over his shoulder. One widely circulated photo, taken by Mike Theiler of Reuters, captured him mid-stride, part of the flag almost glowing with the light coming from the hallway to his left.