Tanya Lewis in Scientific American:

The violent insurrection at the U.S. Capitol Building last week, incited by President Donald Trump, serves as the grimmest moment in one of the darkest chapters in the nation’s history. Yet the rioters’ actions—and Trump’s own role in, and response to, them—come as little surprise to many, particularly those who have been studying the president’s mental fitness and the psychology of his most ardent followers since he took office. One such person is Bandy X. Lee, a forensic psychiatrist and president of the World Mental Health Coalition.

The violent insurrection at the U.S. Capitol Building last week, incited by President Donald Trump, serves as the grimmest moment in one of the darkest chapters in the nation’s history. Yet the rioters’ actions—and Trump’s own role in, and response to, them—come as little surprise to many, particularly those who have been studying the president’s mental fitness and the psychology of his most ardent followers since he took office. One such person is Bandy X. Lee, a forensic psychiatrist and president of the World Mental Health Coalition.

…What attracts people to Trump? What is their animus or driving force?

The reasons are multiple and varied, but in my recent public-service book, Profile of a Nation, I have outlined two major emotional drives: narcissistic symbiosis and shared psychosis. Narcissistic symbiosis refers to the developmental wounds that make the leader-follower relationship magnetically attractive. The leader, hungry for adulation to compensate for an inner lack of self-worth, projects grandiose omnipotence—while the followers, rendered needy by societal stress or developmental injury, yearn for a parental figure. When such wounded individuals are given positions of power, they arouse similar pathology in the population that creates a “lock and key” relationship.

“Shared psychosis”—which is also called “folie à millions” [“madness for millions”] when occurring at the national level or “induced delusions”—refers to the infectiousness of severe symptoms that goes beyond ordinary group psychology. When a highly symptomatic individual is placed in an influential position, the person’s symptoms can spread through the population through emotional bonds, heightening existing pathologies and inducing delusions, paranoia and propensity for violence—even in previously healthy individuals. The treatment is removal of exposure.

More here.

Let’s start with the good news.

Let’s start with the good news.

THE BELIEVER: Your books combine elements of memoir, epistemological analysis, ontological meditation, anthropological observation, and plenty of other genres. They are usually written in the first person (singular or plural), and sometimes in the second person. How did you decide to adopt this freedom of style, and what do you hope to accomplish with it?

THE BELIEVER: Your books combine elements of memoir, epistemological analysis, ontological meditation, anthropological observation, and plenty of other genres. They are usually written in the first person (singular or plural), and sometimes in the second person. How did you decide to adopt this freedom of style, and what do you hope to accomplish with it? She was a poet who could carve both stillness and speed from the gap and one who, for me, lit the match. She was the poet who first taught me to obsess over the responsibility of the line break and in her house, she held her shoulders like a woman no longer afraid to let it be known she liked to be amused. Whatever she and her line breaks had been through, she’d long ago found the courage to say.

She was a poet who could carve both stillness and speed from the gap and one who, for me, lit the match. She was the poet who first taught me to obsess over the responsibility of the line break and in her house, she held her shoulders like a woman no longer afraid to let it be known she liked to be amused. Whatever she and her line breaks had been through, she’d long ago found the courage to say. The violent insurrection at the U.S. Capitol Building last week, incited by President Donald Trump, serves as the grimmest moment in one of the darkest chapters in the nation’s history. Yet the rioters’ actions—and Trump’s own role in, and response to, them—come as little surprise to many, particularly those who have been studying the president’s mental fitness and the psychology of his most ardent followers since he took office. One such person is Bandy X. Lee, a forensic psychiatrist and president of the World Mental Health Coalition.

The violent insurrection at the U.S. Capitol Building last week, incited by President Donald Trump, serves as the grimmest moment in one of the darkest chapters in the nation’s history. Yet the rioters’ actions—and Trump’s own role in, and response to, them—come as little surprise to many, particularly those who have been studying the president’s mental fitness and the psychology of his most ardent followers since he took office. One such person is Bandy X. Lee, a forensic psychiatrist and president of the World Mental Health Coalition. The spectacular violence in the Capitol on January 6th was the outcome of

The spectacular violence in the Capitol on January 6th was the outcome of  Often it seems a shame that those in opposing camps do not take time to stop and appreciate what they have in common: their certainty.

Often it seems a shame that those in opposing camps do not take time to stop and appreciate what they have in common: their certainty. The first full week of 2021 has been action-packed for those of us in the United States of America, for reasons you’re probably aware of, including a riotous mob storming the US Capitol. The situation has spurred me to take the unusual step of doing a solo podcast in response to current events. But never fear, I’m not actually trying to analyze current events for their own sakes. Rather, I’m using them as a jumping-off point for a more general discussion of how democracy is supposed to work and how we can make it better. We’ve talked about related topics recently with

The first full week of 2021 has been action-packed for those of us in the United States of America, for reasons you’re probably aware of, including a riotous mob storming the US Capitol. The situation has spurred me to take the unusual step of doing a solo podcast in response to current events. But never fear, I’m not actually trying to analyze current events for their own sakes. Rather, I’m using them as a jumping-off point for a more general discussion of how democracy is supposed to work and how we can make it better. We’ve talked about related topics recently with  American foreign policy tends to oscillate between inward and outward orientations. President George W. Bush was an interventionist; his successor, Barack Obama, less so. And Donald Trump was mostly non-interventionist. What should we expect from Joe Biden?

American foreign policy tends to oscillate between inward and outward orientations. President George W. Bush was an interventionist; his successor, Barack Obama, less so. And Donald Trump was mostly non-interventionist. What should we expect from Joe Biden? In what would tragically turn out to be the last years of his life, Camus returned imaginatively to the landscape of his youth—a landscape that, because of the Algerian War, was not accessible to him in the way it once had been. In 1958, he agreed to a French edition of The Wrong Side and the Right Side, republished by Gallimard. The timing was significant. “I still live with the idea that my work has not even begun,” Camus wrote in his preface to the new edition. It was an odd claim for a writer who had just been given the Nobel Prize for Literature, but Camus was more troubled by the award than he was honored by it. Pained by the war in his native Algeria, shunned by Parisian intellectuals for his critique of the revolutionary Left, he feared he was finished as a writer—a fear that the Nobel Prize, which usually honors work done over a long career, only served to heighten. Refusing an interview with the newspaper L’Express, Camus explained that he wanted the noise and publicity surrounding the award to die away quickly. “I want to disappear for a while,” he said. To his friend Roger Quinox, he seemed “like someone buried alive.”

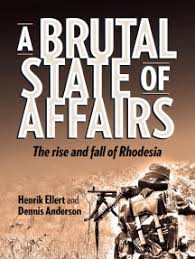

In what would tragically turn out to be the last years of his life, Camus returned imaginatively to the landscape of his youth—a landscape that, because of the Algerian War, was not accessible to him in the way it once had been. In 1958, he agreed to a French edition of The Wrong Side and the Right Side, republished by Gallimard. The timing was significant. “I still live with the idea that my work has not even begun,” Camus wrote in his preface to the new edition. It was an odd claim for a writer who had just been given the Nobel Prize for Literature, but Camus was more troubled by the award than he was honored by it. Pained by the war in his native Algeria, shunned by Parisian intellectuals for his critique of the revolutionary Left, he feared he was finished as a writer—a fear that the Nobel Prize, which usually honors work done over a long career, only served to heighten. Refusing an interview with the newspaper L’Express, Camus explained that he wanted the noise and publicity surrounding the award to die away quickly. “I want to disappear for a while,” he said. To his friend Roger Quinox, he seemed “like someone buried alive.” The authors of this book paint a detailed and dispassionate yet wrenching picture of the painful and bloody transformation of Rhodesia into Zimbabwe in the period following the white leader Ian Smith’s unilateral declaration of independence from Britain in 1965. Their main gift to historians is the wealth of information they provide, much of it hitherto unknown outside secret service circles, about how Rhodesia’s Special Branch, of which the authors themselves were two of the wiliest spooks, helped to keep the forces of African liberation at bay for so long.

The authors of this book paint a detailed and dispassionate yet wrenching picture of the painful and bloody transformation of Rhodesia into Zimbabwe in the period following the white leader Ian Smith’s unilateral declaration of independence from Britain in 1965. Their main gift to historians is the wealth of information they provide, much of it hitherto unknown outside secret service circles, about how Rhodesia’s Special Branch, of which the authors themselves were two of the wiliest spooks, helped to keep the forces of African liberation at bay for so long. Asia has a high number of

Asia has a high number of  The reign of King Louis Philippe, the last king of France, came to an abrupt and ignominious end on Feb. 24, 1848, after days of increasingly violent demonstrations in Paris and months of mounting agitation with the government’s policies. The protesters surging through the city at first were fairly orderly: students chanting, well-dressed men and women strolling, troublemakers breaking windows and looting. But late in the evening of Feb. 23, the tide turned dark. Soldiers had fired on the crowd near the Hôtel des Capucines, leaving scores of men and women gravely wounded. Some blocks away, a journalist was “startled by the aspect of a gentleman who, without his hat, ran madly into the middle of the street, and began to harangue the passers-by. ‘To arms!’ he cried. ‘We are betrayed.’”

The reign of King Louis Philippe, the last king of France, came to an abrupt and ignominious end on Feb. 24, 1848, after days of increasingly violent demonstrations in Paris and months of mounting agitation with the government’s policies. The protesters surging through the city at first were fairly orderly: students chanting, well-dressed men and women strolling, troublemakers breaking windows and looting. But late in the evening of Feb. 23, the tide turned dark. Soldiers had fired on the crowd near the Hôtel des Capucines, leaving scores of men and women gravely wounded. Some blocks away, a journalist was “startled by the aspect of a gentleman who, without his hat, ran madly into the middle of the street, and began to harangue the passers-by. ‘To arms!’ he cried. ‘We are betrayed.’”