Nathaniel Scharping in Undark:

In March, as the Covid-19 pandemic began to shut down major cities in the U.S., researchers were thinking about blood. In particular, they were worried about the U.S. blood supply — the millions of donations every year that help keep hospital patients alive when they need a transfusion.

The researchers were able to put to rest their initial concerns about the virus spreading via the blood supply. But they quickly realized that all those blood donations might offer a vital source of data on the pandemic.

When Covid-19 infects someone, the immune system’s response to the virus leaves behind detectable proteins in their blood. In March, with funding from the National Institutes of Health, a group of scientists working with blood banks around the country quickly launched a program to surveil the blood supply in certain regions for those traces of Covid-19 infection. With funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, that initial program expanded to a nationwide effort known as the Multistate Assessment of SARS-CoV-2 Seroprevalence (MASS) study, which has analyzed roughly 800,000 donations so far.

More here.

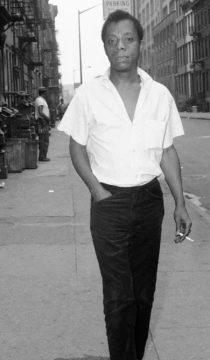

Michael Ondaatje once wrote that if Van Gogh was “our 19th-century artist-saint” then James Baldwin was “our 20th-century one”. For many, Baldwin’s writing has long been a touchstone of anti-racist humanism, but the sense of that particular epithet has never landed more emphatically for me than while reading Eddie S Glaude Jr’s Begin Again, his potent meditation on the enduring legacy of Baldwin’s life and thought, a New York Times bestseller and one of a number of titles that have spoken to the soul of public outrage at

Michael Ondaatje once wrote that if Van Gogh was “our 19th-century artist-saint” then James Baldwin was “our 20th-century one”. For many, Baldwin’s writing has long been a touchstone of anti-racist humanism, but the sense of that particular epithet has never landed more emphatically for me than while reading Eddie S Glaude Jr’s Begin Again, his potent meditation on the enduring legacy of Baldwin’s life and thought, a New York Times bestseller and one of a number of titles that have spoken to the soul of public outrage at  An old man with a shaggy white beard and matching hair stands in front of an audience of seekers and flower children. They are looking for ways of amplifying their human potential, of becoming more aware of their sense perceptions. It’s the tail end of the 1960s and the Esalen Institute in Big Sur, California, is where it’s happening.

An old man with a shaggy white beard and matching hair stands in front of an audience of seekers and flower children. They are looking for ways of amplifying their human potential, of becoming more aware of their sense perceptions. It’s the tail end of the 1960s and the Esalen Institute in Big Sur, California, is where it’s happening.  On Jan. 1, 2021, five long years after the vote for what’s become known as

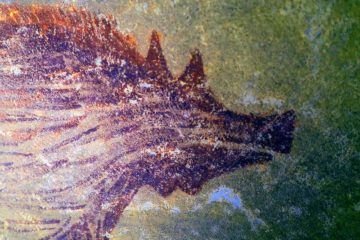

On Jan. 1, 2021, five long years after the vote for what’s become known as  Archaeologists believe they have discovered the world’s oldest-known representational artwork: three wild pigs painted deep in a limestone cave on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi at least 45,500 years ago.

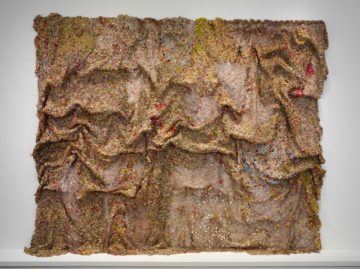

Archaeologists believe they have discovered the world’s oldest-known representational artwork: three wild pigs painted deep in a limestone cave on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi at least 45,500 years ago. Anatsui, a seventy-six-year-old Ghanaian sculptor based in Nigeria, has transfigured many grand spaces with his cascading metal mosaics. Museums don them like regalia, as though to signal their graduation into an enlightened cosmopolitan modernity; they have graced, among other landmarks, the façades of London’s Royal Academy, Venice’s Museo Fortuny, and Marrakech’s El Badi Palace. The sheets sell for millions, attracting collectors as disparate as moma, the Vatican, and Bloomberg L.P. In the past ten years, public fascination with their medium’s trash-to-treasure novelty has matured into a broader appreciation of Anatsui’s significance. The man who dazzled with a formal trick may also be the exemplary sculptor of our precariously networked world.

Anatsui, a seventy-six-year-old Ghanaian sculptor based in Nigeria, has transfigured many grand spaces with his cascading metal mosaics. Museums don them like regalia, as though to signal their graduation into an enlightened cosmopolitan modernity; they have graced, among other landmarks, the façades of London’s Royal Academy, Venice’s Museo Fortuny, and Marrakech’s El Badi Palace. The sheets sell for millions, attracting collectors as disparate as moma, the Vatican, and Bloomberg L.P. In the past ten years, public fascination with their medium’s trash-to-treasure novelty has matured into a broader appreciation of Anatsui’s significance. The man who dazzled with a formal trick may also be the exemplary sculptor of our precariously networked world. I just published a novel in Norway two months ago. I’m now writing another novel which somehow is related, and I’ve started it, I’ve written a hundred pages or so, so I’m in the middle of the beginning of that, which is the hardest part. But that’s what I’m doing.

I just published a novel in Norway two months ago. I’m now writing another novel which somehow is related, and I’ve started it, I’ve written a hundred pages or so, so I’m in the middle of the beginning of that, which is the hardest part. But that’s what I’m doing. In 1972,

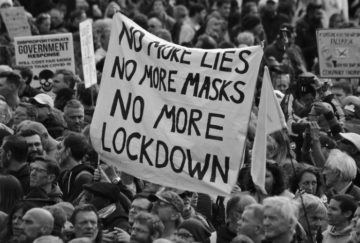

In 1972,  Over the past year, mobilizations around the world have sprung up against governmental efforts to contain the coronavirus through lockdowns, social distancing guidelines, mask mandates, and vaccines. Led in many cases by angry freelancers and the self-employed, amplified by entrepreneurs of speculative and totalizing prophecies, these movements are less what José Ortega y Gasset called “the revolt of the masses” and more “the revolt of the Mittelstand”—small- and medium-sized businesses. In comparison to the populism that dominated discussion in 2017, they are less tethered to mediagenic leaders and parties, slipperier on the traditional political spectrum, and less fixated on the assumption of state power. The spectacular and deadly storming of the U.S. Capitol on January 6 has understandably eclipsed all other mobilizations for the moment. Yet, by drawing back the lens, we can see where aspects of a narrowly defined Trumpism overlap with a broader global phenomenon—and where they do not.

Over the past year, mobilizations around the world have sprung up against governmental efforts to contain the coronavirus through lockdowns, social distancing guidelines, mask mandates, and vaccines. Led in many cases by angry freelancers and the self-employed, amplified by entrepreneurs of speculative and totalizing prophecies, these movements are less what José Ortega y Gasset called “the revolt of the masses” and more “the revolt of the Mittelstand”—small- and medium-sized businesses. In comparison to the populism that dominated discussion in 2017, they are less tethered to mediagenic leaders and parties, slipperier on the traditional political spectrum, and less fixated on the assumption of state power. The spectacular and deadly storming of the U.S. Capitol on January 6 has understandably eclipsed all other mobilizations for the moment. Yet, by drawing back the lens, we can see where aspects of a narrowly defined Trumpism overlap with a broader global phenomenon—and where they do not. But let’s say it again: to call Gray a misanthrope or a reactionary or a nationalist (or to apply to him any other term from the vocabulary of contemporary political morality) is to miss the point. His books are not attacks on humanity as such. Nor is he tubthumping for a particular politics or even a particular morality (I’ll come in a moment to the question of whether or not a specific politics can or should be extracted from Gray’s work). Instead, his books are in the first instance the record of an honourable attempt to discover what can be said about human beings if we dispense, as thoroughly as we can, with the things that human beings have said about themselves. To step out of Gray’s Total Perspective Vortex and ask, “But what’s left?” is to misunderstand the purpose of the Vortex. What’s left, when Gray is finished, is everything: life, death, nature, the universe. All there is, in other words. The point is the seeing. In the final sentence of Straw Dogs, he asks, “Can we not think of the aim of life as being simply to see?”

But let’s say it again: to call Gray a misanthrope or a reactionary or a nationalist (or to apply to him any other term from the vocabulary of contemporary political morality) is to miss the point. His books are not attacks on humanity as such. Nor is he tubthumping for a particular politics or even a particular morality (I’ll come in a moment to the question of whether or not a specific politics can or should be extracted from Gray’s work). Instead, his books are in the first instance the record of an honourable attempt to discover what can be said about human beings if we dispense, as thoroughly as we can, with the things that human beings have said about themselves. To step out of Gray’s Total Perspective Vortex and ask, “But what’s left?” is to misunderstand the purpose of the Vortex. What’s left, when Gray is finished, is everything: life, death, nature, the universe. All there is, in other words. The point is the seeing. In the final sentence of Straw Dogs, he asks, “Can we not think of the aim of life as being simply to see?” The brief examination of the work of Heinrich von Kleist (1777-1811) conducted here is intended as an essay in criticism in the spirit of Sartre: “Une technique romanesque renvoie toujours à la métaphysique du romancier. La tâche du critique est de dégager celle-ci avant d’apprécier celle-là.” The concept of metaphysics Sartre employs refers, on my reading, to the hardly controversial thought that literary works generally (not only novels) render worlds imaginatively present, and that these worlds exhibit principles of intelligibility. To free up the metaphysics of an artistic world, then, is to solicit the deep criteria (or categories) that organize that world. Such criticism brings the form of an aesthetically achieved world to light and demonstrates how that form is made salient linguistically, rhetorically, narratively, dramatically, and so forth. Call this the non-formalistic criticism of form. Needless to say, the account of Kleist’s work I develop here does not aspire to exhaustiveness. The aim, rather, is to limn the contours of Kleist’s artistic achievement such that acknowledgement of its originality and importance is felt to constitute an intellectual obligation. Acknowledgement, a variant of Hegelian “recognition,” deserves to replace the now faded and, in Sartre’s use, merely technical notion of appreciation.

The brief examination of the work of Heinrich von Kleist (1777-1811) conducted here is intended as an essay in criticism in the spirit of Sartre: “Une technique romanesque renvoie toujours à la métaphysique du romancier. La tâche du critique est de dégager celle-ci avant d’apprécier celle-là.” The concept of metaphysics Sartre employs refers, on my reading, to the hardly controversial thought that literary works generally (not only novels) render worlds imaginatively present, and that these worlds exhibit principles of intelligibility. To free up the metaphysics of an artistic world, then, is to solicit the deep criteria (or categories) that organize that world. Such criticism brings the form of an aesthetically achieved world to light and demonstrates how that form is made salient linguistically, rhetorically, narratively, dramatically, and so forth. Call this the non-formalistic criticism of form. Needless to say, the account of Kleist’s work I develop here does not aspire to exhaustiveness. The aim, rather, is to limn the contours of Kleist’s artistic achievement such that acknowledgement of its originality and importance is felt to constitute an intellectual obligation. Acknowledgement, a variant of Hegelian “recognition,” deserves to replace the now faded and, in Sartre’s use, merely technical notion of appreciation. Visualize, if you will, a group of bacteria cells. They are kind of silly looking, when you get right down to it: shaped like a sphere or a pill, sometimes covered in tiny hairs or spikes. While technically alive, it is hard to imagine them as being particularly intelligent, much less capable of storing information like artificially intelligent machines such as computers. Curiously, that’s exactly what a group of researchers just did: edited DNA inside individual bacteria cells in order to store digital data.

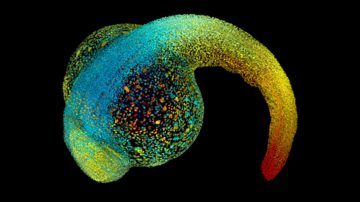

Visualize, if you will, a group of bacteria cells. They are kind of silly looking, when you get right down to it: shaped like a sphere or a pill, sometimes covered in tiny hairs or spikes. While technically alive, it is hard to imagine them as being particularly intelligent, much less capable of storing information like artificially intelligent machines such as computers. Curiously, that’s exactly what a group of researchers just did: edited DNA inside individual bacteria cells in order to store digital data. At first, an embryo has no front or back, head or tail. It’s a simple sphere of cells. But soon enough, the smooth clump begins to change. Fluid pools in the middle of the sphere. Cells flow like honey to take up their positions in the future body. Sheets of cells fold origami-style, building a heart, a gut, a brain. None of this could happen without forces that squeeze, bend and tug the growing animal into shape. Even when it reaches adulthood, its cells will continue to respond to pushing and pulling — by each other and from the environment. Yet the manner in which bodies and tissues take form remains “one of the most important, and still poorly understood, questions of our time”, says developmental biologist Amy Shyer, who studies morphogenesis at the Rockefeller University in New York City. For decades, biologists have focused on the ways in which genes and other biomolecules shape bodies, mainly because the tools to analyse these signals are readily available and always improving. Mechanical forces have received much less attention.

At first, an embryo has no front or back, head or tail. It’s a simple sphere of cells. But soon enough, the smooth clump begins to change. Fluid pools in the middle of the sphere. Cells flow like honey to take up their positions in the future body. Sheets of cells fold origami-style, building a heart, a gut, a brain. None of this could happen without forces that squeeze, bend and tug the growing animal into shape. Even when it reaches adulthood, its cells will continue to respond to pushing and pulling — by each other and from the environment. Yet the manner in which bodies and tissues take form remains “one of the most important, and still poorly understood, questions of our time”, says developmental biologist Amy Shyer, who studies morphogenesis at the Rockefeller University in New York City. For decades, biologists have focused on the ways in which genes and other biomolecules shape bodies, mainly because the tools to analyse these signals are readily available and always improving. Mechanical forces have received much less attention. Mr. Faruqi has been credited among scholars with the revival of Urdu literature, especially from the 18th and 19th centuries. His output as a scholar, editor, publisher, critic, literary historian, translator and acclaimed writer of both poetry and novels was varied and prolific.

Mr. Faruqi has been credited among scholars with the revival of Urdu literature, especially from the 18th and 19th centuries. His output as a scholar, editor, publisher, critic, literary historian, translator and acclaimed writer of both poetry and novels was varied and prolific.