Ed Yong in The Atlantic:

The coronavirus pandemic ignited at the end of 2019 and blazed across 2020. Many countries repeatedly contained it. The United States did not. At least 19 million Americans have been infected. At least 326,000 have died. The first two surges, in the spring and summer, plateaued but never significantly subsided. The third and worst is still ongoing. In December, an average of 2,379 Americans have died every day of COVID-19—comparable to the 2,403 who died in Pearl Harbor and the 2,977 who died in the 9/11 attacks. The virus now has so much momentum that more infection and death are inevitable as the second full year of the pandemic begins. “There will be a whole lot of pain in the first quarter” of 2021, Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told me.

The coronavirus pandemic ignited at the end of 2019 and blazed across 2020. Many countries repeatedly contained it. The United States did not. At least 19 million Americans have been infected. At least 326,000 have died. The first two surges, in the spring and summer, plateaued but never significantly subsided. The third and worst is still ongoing. In December, an average of 2,379 Americans have died every day of COVID-19—comparable to the 2,403 who died in Pearl Harbor and the 2,977 who died in the 9/11 attacks. The virus now has so much momentum that more infection and death are inevitable as the second full year of the pandemic begins. “There will be a whole lot of pain in the first quarter” of 2021, Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told me.

But that pain could soon start to recede. Two vaccines have been developed and approved in less time than many experts predicted, and are more effective than they dared hope. Joe Biden, the incoming president, has promised to push for measures that health specialists have championed in vain for months. He has filled his administration and COVID-19 task force with seasoned scientists and medics. His chief of staff, Ron Klain, coordinated America’s response to the Ebola outbreak of 2014. His pick for CDC director, Rochelle Walensky, is a widely respected infectious-disease doctor and skilled communicator. The winter months will still be abyssally dark, but every day promises to bring a little more light.

More here.

The Complete Works of Alberto Caeiro, translated by Margaret Jull Costa and Patricio Ferrari, presents the work of a complicated man. Caeiro was born in Lisbon in 1889, but he spent most of his life in the countryside. He received almost no formal education, but he was a passionate poet. At 25, he died of tuberculosis. Looking back, we can only be sure of one fact regarding Caeiro: He did not exist.

The Complete Works of Alberto Caeiro, translated by Margaret Jull Costa and Patricio Ferrari, presents the work of a complicated man. Caeiro was born in Lisbon in 1889, but he spent most of his life in the countryside. He received almost no formal education, but he was a passionate poet. At 25, he died of tuberculosis. Looking back, we can only be sure of one fact regarding Caeiro: He did not exist. Michael Baker figures he was the first public health expert in the world to talk about eliminating Covid-19, though he’s not sure why.

Michael Baker figures he was the first public health expert in the world to talk about eliminating Covid-19, though he’s not sure why. Since Rohr founded the Center for Action and Contemplation in 1987, his aim has been to revive the Christian contemplative tradition. For a growing number of Christendom’s defectors, his teachings have provided a bridge, even a destination. Through conferences, podcasts, dozens of books, a two-year curriculum called the Living School, and his newsletter, Rohr has become a leading voice for a growing population within American Christianity: those who were leaving the church not because they were done with Christianity, but because they were drawn to its more ancient, mystical expressions. In addition to the two thousand attendees from fifty states and fifteen countries, nearly three thousand more people from forty-two countries joined via webcast. I bought one of the last tickets before the conference sold out. To his credit, Rohr is quick to say that whatever popularity he enjoys is not because of himself—“God deliberately made me not so good-looking. I’m short and dumpy, a B student . . . and I don’t think I’m a saint”—but because he speaks on behalf of what he calls the perennial tradition, a lineage rooted in Christianity but that he says is present in all faiths.

Since Rohr founded the Center for Action and Contemplation in 1987, his aim has been to revive the Christian contemplative tradition. For a growing number of Christendom’s defectors, his teachings have provided a bridge, even a destination. Through conferences, podcasts, dozens of books, a two-year curriculum called the Living School, and his newsletter, Rohr has become a leading voice for a growing population within American Christianity: those who were leaving the church not because they were done with Christianity, but because they were drawn to its more ancient, mystical expressions. In addition to the two thousand attendees from fifty states and fifteen countries, nearly three thousand more people from forty-two countries joined via webcast. I bought one of the last tickets before the conference sold out. To his credit, Rohr is quick to say that whatever popularity he enjoys is not because of himself—“God deliberately made me not so good-looking. I’m short and dumpy, a B student . . . and I don’t think I’m a saint”—but because he speaks on behalf of what he calls the perennial tradition, a lineage rooted in Christianity but that he says is present in all faiths. Since 2011, a monument to Martin Luther King, Jr., has sat across the water from the Jefferson Memorial, almost engaging it in a staring contest. The result is a rich spatial symbolism: two ways of seeing Christ duking it out. King saw Jesus in much the way that Douglass did: as a savior, a redeemer, and a liberator sorely degraded by those who claimed his name most loudly. During the Montgomery bus boycott, King reportedly carried a copy of “

Since 2011, a monument to Martin Luther King, Jr., has sat across the water from the Jefferson Memorial, almost engaging it in a staring contest. The result is a rich spatial symbolism: two ways of seeing Christ duking it out. King saw Jesus in much the way that Douglass did: as a savior, a redeemer, and a liberator sorely degraded by those who claimed his name most loudly. During the Montgomery bus boycott, King reportedly carried a copy of “ Most of the 74,222,957 Americans who voted to re-elect

Most of the 74,222,957 Americans who voted to re-elect  O

O Many people make New Year’s resolutions. The

Many people make New Year’s resolutions. The  In the popular science world, physicist John Wheeler is probably best known for popularizing the term “black hole,” although his research spanned a broad range of fields, including relativity, quantum theory, and nuclear fission. He also worked on Project Matterhorn B in the early 1950s, the controversial US effort to develop a hydrogen bomb. In January 1953, Wheeler accidentally left a highly classified document concerning that program on a train as he traveled from his Princeton, New Jersey home to Washington, DC. It was a stereotypical “

In the popular science world, physicist John Wheeler is probably best known for popularizing the term “black hole,” although his research spanned a broad range of fields, including relativity, quantum theory, and nuclear fission. He also worked on Project Matterhorn B in the early 1950s, the controversial US effort to develop a hydrogen bomb. In January 1953, Wheeler accidentally left a highly classified document concerning that program on a train as he traveled from his Princeton, New Jersey home to Washington, DC. It was a stereotypical “ Our family had been fortunate. Ali was too young for school. Anna’s job allowed her to telework during the pandemic. Unlike many parents, we didn’t have to worry about money or child care. Our little boy adapted well to social isolation. He read, played catch and helped me cook. We explored local parks and ponds, avoiding people and chasing ducks.

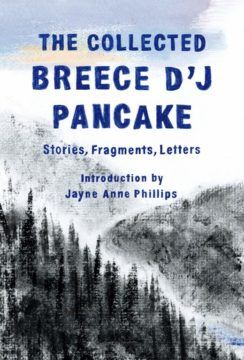

Our family had been fortunate. Ali was too young for school. Anna’s job allowed her to telework during the pandemic. Unlike many parents, we didn’t have to worry about money or child care. Our little boy adapted well to social isolation. He read, played catch and helped me cook. We explored local parks and ponds, avoiding people and chasing ducks. Pancake’s depictions of the culture and geography of Appalachia and the Trans-Allegheny were all but unprecedented. The hills and hollows of West Virginia were largely neglected in American literature, even the intensely regionalist literatures of the South, possibly because West Virginia had fought with the Union during the Civil War, and so had little to contribute to the revisionist horseshit of Lost Cause sentimentality. Pancake seems to know everything about this place, from its hilltops to its coal mines to its barrooms, and he has an eye for the small, sharp details that bring it to life. In “Hollow,” when Buddy wakes up on the floor of his trailer after a night of drinking and brawling, there is “a little ball of rayon batting against his nostril as he breathed.” Bo, in “Fox Hunters,” “stepped onto the pavement feeling tired and moved a few paces until headlights flooded his path, showing up the highway steam and making the road give birth to little ghosts beneath his feet.” At the same time, Pancake is always attentive to the natural world. He finds a kind of holiness in the history-dwarfing scale of geologic time.

Pancake’s depictions of the culture and geography of Appalachia and the Trans-Allegheny were all but unprecedented. The hills and hollows of West Virginia were largely neglected in American literature, even the intensely regionalist literatures of the South, possibly because West Virginia had fought with the Union during the Civil War, and so had little to contribute to the revisionist horseshit of Lost Cause sentimentality. Pancake seems to know everything about this place, from its hilltops to its coal mines to its barrooms, and he has an eye for the small, sharp details that bring it to life. In “Hollow,” when Buddy wakes up on the floor of his trailer after a night of drinking and brawling, there is “a little ball of rayon batting against his nostril as he breathed.” Bo, in “Fox Hunters,” “stepped onto the pavement feeling tired and moved a few paces until headlights flooded his path, showing up the highway steam and making the road give birth to little ghosts beneath his feet.” At the same time, Pancake is always attentive to the natural world. He finds a kind of holiness in the history-dwarfing scale of geologic time. Both The Divine Comedy and Piers Plowman express verities accessed by the mind in repose; Langland’s poem, for not beginning in a dark wood but rather in a sunny field, embodies mystical apprehensions as surely as does Dante. A key difference is that Langland’s allegory is so obvious (as anyone who has seen the medieval play

Both The Divine Comedy and Piers Plowman express verities accessed by the mind in repose; Langland’s poem, for not beginning in a dark wood but rather in a sunny field, embodies mystical apprehensions as surely as does Dante. A key difference is that Langland’s allegory is so obvious (as anyone who has seen the medieval play  What tone can one possibly strike for an overview of 2020? The Queen’s old label of annus horribilis for her own most troubled time hardly seems adequate. Even the right point of view is hard to decide on. Does it make more sense to see the year from high above, taking a picture of an entire panicked planet, or to start from the ant’s- or worm’s-eye view, with the transformation of our manners and minds by the strangeness of 2020 (and by its sadness, too)? Begin with the scale of the misery and dislocation? Narrow down to the specific sensory strangeness of the year?

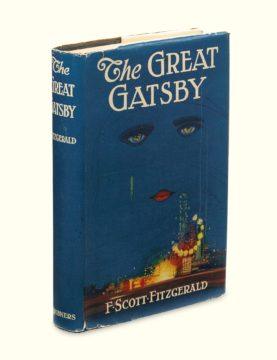

What tone can one possibly strike for an overview of 2020? The Queen’s old label of annus horribilis for her own most troubled time hardly seems adequate. Even the right point of view is hard to decide on. Does it make more sense to see the year from high above, taking a picture of an entire panicked planet, or to start from the ant’s- or worm’s-eye view, with the transformation of our manners and minds by the strangeness of 2020 (and by its sadness, too)? Begin with the scale of the misery and dislocation? Narrow down to the specific sensory strangeness of the year? One of the pleasures of writing about a book as widely read as “The Great Gatsby” is jetting through the obligatory plot summary. You recall Nick Carraway, our narrator, who moves next door to the mysteriously wealthy Jay Gatsby on Long Island. Gatsby, it turns out, is pining for Nick’s cousin, Daisy; his glittering life is a lure to impress her, win her back. Daisy is inconveniently married to the brutish Tom Buchanan, who, in turn, is carrying on with a married woman, the doomed Myrtle. Cue the parties, the affairs, Nick getting very queasy about it all. In a lurid climax, Myrtle is run over by a car driven by Daisy. Gatsby is blamed; Myrtle’s husband shoots him dead in his pool and kills himself. The Buchanans discreetly leave town, their hands clean. Nick is writing the book, we understand, two years later, in a frenzy of disgust.

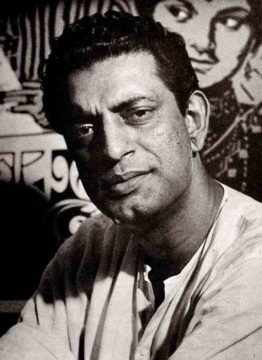

One of the pleasures of writing about a book as widely read as “The Great Gatsby” is jetting through the obligatory plot summary. You recall Nick Carraway, our narrator, who moves next door to the mysteriously wealthy Jay Gatsby on Long Island. Gatsby, it turns out, is pining for Nick’s cousin, Daisy; his glittering life is a lure to impress her, win her back. Daisy is inconveniently married to the brutish Tom Buchanan, who, in turn, is carrying on with a married woman, the doomed Myrtle. Cue the parties, the affairs, Nick getting very queasy about it all. In a lurid climax, Myrtle is run over by a car driven by Daisy. Gatsby is blamed; Myrtle’s husband shoots him dead in his pool and kills himself. The Buchanans discreetly leave town, their hands clean. Nick is writing the book, we understand, two years later, in a frenzy of disgust. It seems that there are all kinds of unresolved problems to do with Satyajit Ray – to do with thinking about him, with finding a language to speak about him that does not repeat the indubitable truisms about his humanism and lyricism. How does he fit into history, and into which history – the history of India; the history of filmmaking; some other – do we place him first?

It seems that there are all kinds of unresolved problems to do with Satyajit Ray – to do with thinking about him, with finding a language to speak about him that does not repeat the indubitable truisms about his humanism and lyricism. How does he fit into history, and into which history – the history of India; the history of filmmaking; some other – do we place him first?