Jay Kang in The New Yorker:

One of the stultifying but ultimately true maxims of the analytics movement in sports says that most narratives around player performance are lies. Each player has a “true talent level” based on their abilities, but the actual results are mostly up to variance and luck. If a player has, say, the true talent to hit thirty-one home runs in a season, the timing of those home runs is mostly random. If someone hits a third of those in April, that doesn’t really mean he’s a “hot starter” who is “building off a great spring”—it just means that if you take thirty-one home runs and toss them up in the air to land randomly on a time line, sometimes ten of them float over to April. What does matter, the analytics guys say, are plate appearances: you have to clock in enough opportunities to realize your true talent level.

One of the stultifying but ultimately true maxims of the analytics movement in sports says that most narratives around player performance are lies. Each player has a “true talent level” based on their abilities, but the actual results are mostly up to variance and luck. If a player has, say, the true talent to hit thirty-one home runs in a season, the timing of those home runs is mostly random. If someone hits a third of those in April, that doesn’t really mean he’s a “hot starter” who is “building off a great spring”—it just means that if you take thirty-one home runs and toss them up in the air to land randomly on a time line, sometimes ten of them float over to April. What does matter, the analytics guys say, are plate appearances: you have to clock in enough opportunities to realize your true talent level.

For much of my career, I was the type of journalist who only published a handful of magazine pieces a year. These required a great deal of time, much of which was spent on minor improvements to the reporting, structure, and sentences. I believed that long-form journalism, much like fiction or poetry, possessed a near-mystical rhythm that could be accessed through months of intensive labor. Once unlocked, some spirit would sing through the piece and touch the readers in a universal, truthful way.

More here.

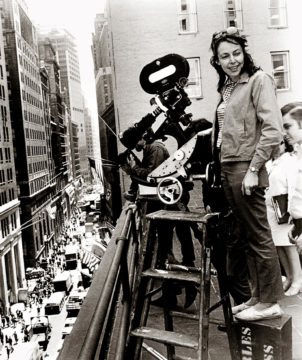

Those who don’t already admire Hardwick’s writing likely know her from her marriage to poet Robert Lowell. It is at times a lurid story. A masterful poet, Lowell was also bipolar at a time when treatment was (as it still can be for many) uncertain and inconsistent. During manic episodes, he could be cruel to his wife. (“Everybody has noticed that you’ve been getting pretty dumb lately,” he told her during one episode.) While she worked to keep their household together, ensure bills were paid, and oversee his care, he would call her family to tell them he never loved her. His mania often coincided with brazen affairs; friends, colleagues, and even doctors sometimes suspected Hardwick of jealousy when she tried to get him help. When he finally left her after 20 years of marriage, he wrote a collection of poems—dedicated to his new wife, Caroline Blackwood—that excerpted his ex-wife’s plaintive letters to him and (perhaps the worse betrayal) fabricated others without noting the difference. The Dolphin was condemned by friends like Elizabeth Bishop and Adrienne Rich, but it also won the National Book Award. (In a published review, Rich called the book “one of the most vindictive and mean-spirited acts in the history of poetry.”) Years later, Lowell and Hardwick reconciled. Visiting her in New York not long after, he took a taxi from the airport and died before arriving. Summoned by the cab driver, Hardwick rode alongside Lowell to the hospital, knowing that he was already dead.

Those who don’t already admire Hardwick’s writing likely know her from her marriage to poet Robert Lowell. It is at times a lurid story. A masterful poet, Lowell was also bipolar at a time when treatment was (as it still can be for many) uncertain and inconsistent. During manic episodes, he could be cruel to his wife. (“Everybody has noticed that you’ve been getting pretty dumb lately,” he told her during one episode.) While she worked to keep their household together, ensure bills were paid, and oversee his care, he would call her family to tell them he never loved her. His mania often coincided with brazen affairs; friends, colleagues, and even doctors sometimes suspected Hardwick of jealousy when she tried to get him help. When he finally left her after 20 years of marriage, he wrote a collection of poems—dedicated to his new wife, Caroline Blackwood—that excerpted his ex-wife’s plaintive letters to him and (perhaps the worse betrayal) fabricated others without noting the difference. The Dolphin was condemned by friends like Elizabeth Bishop and Adrienne Rich, but it also won the National Book Award. (In a published review, Rich called the book “one of the most vindictive and mean-spirited acts in the history of poetry.”) Years later, Lowell and Hardwick reconciled. Visiting her in New York not long after, he took a taxi from the airport and died before arriving. Summoned by the cab driver, Hardwick rode alongside Lowell to the hospital, knowing that he was already dead. May, by contrast, the elusive

May, by contrast, the elusive  It was a source of some annoyance to Charles Portis that Shakespeare never wrote about Arkansas. As the novelist pointed out, it wasn’t, strictly speaking, impossible: Hernando de Soto had ventured to the area in 1541, members of his expedition wrote about their travels in journals that were translated into English, and at least one of those accounts was circulating in London when Shakespeare was working there in 1609. To Portis, it was also perfectly obvious that the exploration of his home state could have been fine fodder for the Bard: “It is just the kind of chronicle he quarried for his plots and characters, and DeSoto, a brutal, devout, heroic man brought low, is certainly of Shakespearean stature. But, bad luck, there is no play, with a scene at the Camden winter quarters, and, in another part of the forest, at Smackover Creek, where willows still grow aslant the brook.”

It was a source of some annoyance to Charles Portis that Shakespeare never wrote about Arkansas. As the novelist pointed out, it wasn’t, strictly speaking, impossible: Hernando de Soto had ventured to the area in 1541, members of his expedition wrote about their travels in journals that were translated into English, and at least one of those accounts was circulating in London when Shakespeare was working there in 1609. To Portis, it was also perfectly obvious that the exploration of his home state could have been fine fodder for the Bard: “It is just the kind of chronicle he quarried for his plots and characters, and DeSoto, a brutal, devout, heroic man brought low, is certainly of Shakespearean stature. But, bad luck, there is no play, with a scene at the Camden winter quarters, and, in another part of the forest, at Smackover Creek, where willows still grow aslant the brook.” At 53, Suga Free still looks exactly like Suga Free. Honoring his commandment to be fly for life, his hair remains long and luxurious. He’s draped in a custom-made tracksuit with his name emblazoned on the back. The right questions elicit stanzas of profane one-liners, flamboyant slang and coldblooded wisdom. (“Every time I walk out of my house and turn that key in my car, that means I’m finna spend some money,” he laughs. “I’m trying to squeeze a quarter till the eagle screams.”) Ask the wrong question and you don’t want the answer.

At 53, Suga Free still looks exactly like Suga Free. Honoring his commandment to be fly for life, his hair remains long and luxurious. He’s draped in a custom-made tracksuit with his name emblazoned on the back. The right questions elicit stanzas of profane one-liners, flamboyant slang and coldblooded wisdom. (“Every time I walk out of my house and turn that key in my car, that means I’m finna spend some money,” he laughs. “I’m trying to squeeze a quarter till the eagle screams.”) Ask the wrong question and you don’t want the answer. It’s coming. Winds are weakening along the equatorial Pacific Ocean. Heat is building beneath the ocean surface. By July,

It’s coming. Winds are weakening along the equatorial Pacific Ocean. Heat is building beneath the ocean surface. By July,  It might feel pretty obvious to you that you’re weak-willed. You feel it, after all – every time you find yourself hitting the snooze button on the alarm when you know you ought to get out of bed; every time you scroll through cat videos on Instagram when you know you ought to be writing; every time you help yourself to a third slice of cake when you know you ought to order a kale smoothie instead. When you find yourself in these situations, there’s often a bit of shame, a bit of guilt, a bit of frustration. In many cases, the subsequent conviction that we’re weak-willed shapes our entire approach to motivating ourselves.

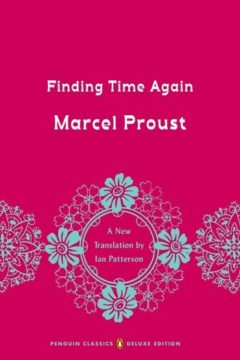

It might feel pretty obvious to you that you’re weak-willed. You feel it, after all – every time you find yourself hitting the snooze button on the alarm when you know you ought to get out of bed; every time you scroll through cat videos on Instagram when you know you ought to be writing; every time you help yourself to a third slice of cake when you know you ought to order a kale smoothie instead. When you find yourself in these situations, there’s often a bit of shame, a bit of guilt, a bit of frustration. In many cases, the subsequent conviction that we’re weak-willed shapes our entire approach to motivating ourselves. Patterson, a poet, essayist, and translator, has a good ear for the sonic qualities of the Recherche’s prose. This is particularly notable in the opening of the volume. Finding Time Again begins with one of Proust’s analogies between nature and artifice, couched in a meandering, multiclausal sentence that is, nonetheless, beautifully balanced in its Byzantine way, culminating in one of Proust’s classic, grammatical course corrections in which, after drifting away from the initial subject in a metaphorizing reverie, the sentence begins all over again without ending, usually after the nominal concession of a semicolon: “Toute la journée,” it begins, “all day long” as Patterson renders it, before describing the “slightly too bucolic residence” where the narrator finds himself,

Patterson, a poet, essayist, and translator, has a good ear for the sonic qualities of the Recherche’s prose. This is particularly notable in the opening of the volume. Finding Time Again begins with one of Proust’s analogies between nature and artifice, couched in a meandering, multiclausal sentence that is, nonetheless, beautifully balanced in its Byzantine way, culminating in one of Proust’s classic, grammatical course corrections in which, after drifting away from the initial subject in a metaphorizing reverie, the sentence begins all over again without ending, usually after the nominal concession of a semicolon: “Toute la journée,” it begins, “all day long” as Patterson renders it, before describing the “slightly too bucolic residence” where the narrator finds himself, S

S In Jo Walton’s 2019 fantasy novel

In Jo Walton’s 2019 fantasy novel  Can money buy happiness? Two authors of this article have published contradictory claims about the relationship between emotional well-being and income. We later agreed that both studies produced valid results and that it was our responsibility to search for an interpretation that explains both findings. We engaged in an adversarial collaboration and asked Barbara Mellers to be the facilitator. This article reports the outcome of our work.

Can money buy happiness? Two authors of this article have published contradictory claims about the relationship between emotional well-being and income. We later agreed that both studies produced valid results and that it was our responsibility to search for an interpretation that explains both findings. We engaged in an adversarial collaboration and asked Barbara Mellers to be the facilitator. This article reports the outcome of our work. The year 2023 is still young, and already there have been at least

The year 2023 is still young, and already there have been at least  I first read Carl Sagan’s Contact and Cosmos in high school, when I was working at a bookstore that let us borrow any book we had at least two copies of on the shelves. I loved them then and was excited to revisit these books in the course of my research for The Possibility of Life. A scene from Cosmos had stayed with me—and confounded me—for almost twenty years, and I was ready to make new sense of it. But when I got to the place in the book where the scene should have been, the chapter just ended.

I first read Carl Sagan’s Contact and Cosmos in high school, when I was working at a bookstore that let us borrow any book we had at least two copies of on the shelves. I loved them then and was excited to revisit these books in the course of my research for The Possibility of Life. A scene from Cosmos had stayed with me—and confounded me—for almost twenty years, and I was ready to make new sense of it. But when I got to the place in the book where the scene should have been, the chapter just ended.

For Rick Doblin, 2023 could be a landmark year: the year that the US government decides whether it will allow the

For Rick Doblin, 2023 could be a landmark year: the year that the US government decides whether it will allow the