Yoshua Bengio at his own website:

There is no guarantee that someone in the foreseeable future won’t develop dangerous autonomous AI systems with behaviors that deviate from human goals and values. The short and medium term risks –manipulation of public opinion for political purposes, especially through disinformation– are easy to predict, unlike the longer term risks –AI systems that are harmful despite the programmers’ objectives,– and I think it is important to study both.

There is no guarantee that someone in the foreseeable future won’t develop dangerous autonomous AI systems with behaviors that deviate from human goals and values. The short and medium term risks –manipulation of public opinion for political purposes, especially through disinformation– are easy to predict, unlike the longer term risks –AI systems that are harmful despite the programmers’ objectives,– and I think it is important to study both.

With the arrival of ChatGPT, we have witnessed a shift in the attitudes of companies, for whom the challenge of commercial competition has increased tenfold. There is a real risk that they will rush into developing these giant AI systems, leaving behind good habits of transparency and open science they have developed over the past decade of AI research.

There is an urgent need to regulate these systems by aiming for more transparency and oversight of AI systems to protect society. I believe, as many do, that the risks and uncertainty have reached such a level that it requires an acceleration also in the development of our governance mechanisms.

More here.

This issue of Lapham’s Quarterly bravely addresses the hotly contested word freedom. It is hotly contested in part because what the word means has never been clear, a fact that has not seemed to lessen its importance for us. It is a word in which we have invested enormous amounts of energy without producing much in the way of illumination. And yet freedom cannot be dismissed simply on semantic grounds—“just another word,” as Kris Kristofferson sang—because what is at its heart may very well answer the question “What does it mean to be human?”

This issue of Lapham’s Quarterly bravely addresses the hotly contested word freedom. It is hotly contested in part because what the word means has never been clear, a fact that has not seemed to lessen its importance for us. It is a word in which we have invested enormous amounts of energy without producing much in the way of illumination. And yet freedom cannot be dismissed simply on semantic grounds—“just another word,” as Kris Kristofferson sang—because what is at its heart may very well answer the question “What does it mean to be human?” S

S

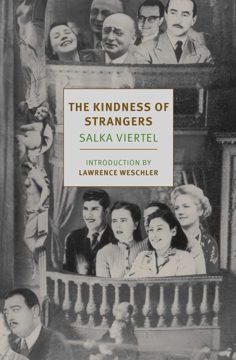

Nowadays the title reads not only as tepid and banal but as distinctly unrepresentative of the ensuing narrative’s principal themes and contours. In fairness, when the onetime Austro-Hungarian actress and subsequently Hollywood scenarist Salka Viertel first began auditioning the phrase “the kindness of strangers” for the title of her memoir in progress, back in the mid-1950s, as her recent biographer Donna Rifkind has pointed out, the words were not nearly as hackneyed as they are today. (The sensational play A Streetcar Named Desire, from which they sprang, was only a few years old, having premiered in 1947; the film had only been released in 1951; and the primary chestnut to have emerged from the latter was Stanley’s bloodcurdling scream of “Stella! Stellllaaaa!” and not so much Blanche’s breathy Southern belle protestations of having always reliii-ed on the kindness of strangers.) Salka’s husband, the internationally acclaimed theater director Berthold Viertel, had been translating their friend Tennessee Williams’s plays for some years already and staging them all over Europe, and perhaps Salka savored the nod in the young playwright’s direction. Such selfless generosity, indeed such kindness on her own part, would have been just like her.

Nowadays the title reads not only as tepid and banal but as distinctly unrepresentative of the ensuing narrative’s principal themes and contours. In fairness, when the onetime Austro-Hungarian actress and subsequently Hollywood scenarist Salka Viertel first began auditioning the phrase “the kindness of strangers” for the title of her memoir in progress, back in the mid-1950s, as her recent biographer Donna Rifkind has pointed out, the words were not nearly as hackneyed as they are today. (The sensational play A Streetcar Named Desire, from which they sprang, was only a few years old, having premiered in 1947; the film had only been released in 1951; and the primary chestnut to have emerged from the latter was Stanley’s bloodcurdling scream of “Stella! Stellllaaaa!” and not so much Blanche’s breathy Southern belle protestations of having always reliii-ed on the kindness of strangers.) Salka’s husband, the internationally acclaimed theater director Berthold Viertel, had been translating their friend Tennessee Williams’s plays for some years already and staging them all over Europe, and perhaps Salka savored the nod in the young playwright’s direction. Such selfless generosity, indeed such kindness on her own part, would have been just like her. Walter was tall and gaunt with a hard-to-place, vaguely English accent. He favored Kools and Chardonnay, and he was never photographed in anything but a dark suit, a tiny smile often curling at the corner of his mouth. His public profile was about to explode. A publisher was finalizing a book about the

Walter was tall and gaunt with a hard-to-place, vaguely English accent. He favored Kools and Chardonnay, and he was never photographed in anything but a dark suit, a tiny smile often curling at the corner of his mouth. His public profile was about to explode. A publisher was finalizing a book about the  Nothing really prepares one for the experience of entering the

Nothing really prepares one for the experience of entering the  Last August, the author

Last August, the author  For the last 60 years or so, science has been running an experiment on itself. The experimental design wasn’t great; there was no randomization and no control group. Nobody was in charge, exactly, and nobody was really taking consistent measurements. And yet it was the most massive experiment ever run, and it included every scientist on Earth.

For the last 60 years or so, science has been running an experiment on itself. The experimental design wasn’t great; there was no randomization and no control group. Nobody was in charge, exactly, and nobody was really taking consistent measurements. And yet it was the most massive experiment ever run, and it included every scientist on Earth. Many opponents of Netanyahu’s judicial overhaul have called for Israel to finally draft a constitution, but any serious attempt will mean choosing between a democratic state and one that privileges Jewish citizens above all others.

Many opponents of Netanyahu’s judicial overhaul have called for Israel to finally draft a constitution, but any serious attempt will mean choosing between a democratic state and one that privileges Jewish citizens above all others. “She had no sympathy,” Spiegelman tells us, “for people who paraded their inner misfortunes.” Clampitt’s dismissive attitude toward the self-indulgences of confessional verse, which commanded so much attention in the 1960s and 1970s, was a product, he writes, of “her stern midwestern upbringing.” And her models: Hopkins,

“She had no sympathy,” Spiegelman tells us, “for people who paraded their inner misfortunes.” Clampitt’s dismissive attitude toward the self-indulgences of confessional verse, which commanded so much attention in the 1960s and 1970s, was a product, he writes, of “her stern midwestern upbringing.” And her models: Hopkins,  One morning in Maine, soon after dawn, I stood by the ocean just as a light fog began moving in. The rising sun became a gauzy fire. Suddenly, the air started to glow. Fog scattered the sunlight, bounced it around and back and forth until each cupful of air shone with its own source of light. In all directions, the air beamed and shimmered and glowed, and the gulls stopped their squawking and the ospreys became quiet. For some time, I stood there spellbound by the silence and the glowing air. I felt as if inside a cathedral of sunlight and air. Then the fog burned away and the glow disappeared.

One morning in Maine, soon after dawn, I stood by the ocean just as a light fog began moving in. The rising sun became a gauzy fire. Suddenly, the air started to glow. Fog scattered the sunlight, bounced it around and back and forth until each cupful of air shone with its own source of light. In all directions, the air beamed and shimmered and glowed, and the gulls stopped their squawking and the ospreys became quiet. For some time, I stood there spellbound by the silence and the glowing air. I felt as if inside a cathedral of sunlight and air. Then the fog burned away and the glow disappeared. The federal raid on the Branch Davidian compound, thirty years ago, was flawed from the start.

The federal raid on the Branch Davidian compound, thirty years ago, was flawed from the start.  What is it about Rainer Maria Rilke? The influence of the Bohemian Austrian poet on modern culture reads like a who’s who of the great and the good. W. H. Auden, Cecil Day-Lewis, and Edith Sitwell claimed to be directly inspired by him. The first English translations of his work, published by Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s Hogarth Press, became classics in their own right. He has been set to music (both classical and rock) and proven himself a Hollywood touchstone, most recently providing the

What is it about Rainer Maria Rilke? The influence of the Bohemian Austrian poet on modern culture reads like a who’s who of the great and the good. W. H. Auden, Cecil Day-Lewis, and Edith Sitwell claimed to be directly inspired by him. The first English translations of his work, published by Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s Hogarth Press, became classics in their own right. He has been set to music (both classical and rock) and proven himself a Hollywood touchstone, most recently providing the