Diana Kwon in Nautilus:

Jane McKeating never expected time to matter much in the liver.

Jane McKeating never expected time to matter much in the liver.

About a decade ago, McKeating was examining medications to use during liver transplantation in patients with chronic hepatitis C infections. Hepatitis C can linger in the body for decades and cause severe liver damage—and in those days, the lack of drugs to combat the viral infection meant that when a patient received a replacement liver, the virus could immediately infect the new organ. McKeating, then a virologist at the University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom, and her colleagues wanted to see whether an antiviral drug could stop the virus’ spread and save the new livers.

When the team initially assessed their data, they were stumped. It looked like the drug prevented infection in some patients, but not others—and it wasn’t clear what, exactly, was behind this difference. “We just couldn’t understand what was discriminating between the patients,” says McKeatin, now at the University of Oxford. After much head scratching, they noticed a perplexing pattern: Patients who received their liver transplants in the morning were more likely to be reinfected with the hepatitis C virus than those who had their operations in the afternoon.1 “It turned out it was the time of day when they received the liver transplant,” she says.

More here.

Please pause for a moment and notice what you are feeling now. Perhaps you notice a growing snarl of hunger in your stomach or a hum of stress in your chest. Perhaps you have a feeling of ease and expansiveness, or the tingling anticipation of a pleasure soon to come. Or perhaps you simply have a sense that you exist. Hunger and thirst, pain, pleasure and distress, along with the unadorned but relentless feelings of existence, are all examples of ‘homeostatic feelings’. Homeostatic feelings are, we argue here, the source of consciousness.

Please pause for a moment and notice what you are feeling now. Perhaps you notice a growing snarl of hunger in your stomach or a hum of stress in your chest. Perhaps you have a feeling of ease and expansiveness, or the tingling anticipation of a pleasure soon to come. Or perhaps you simply have a sense that you exist. Hunger and thirst, pain, pleasure and distress, along with the unadorned but relentless feelings of existence, are all examples of ‘homeostatic feelings’. Homeostatic feelings are, we argue here, the source of consciousness. It’s not an exaggeration to say that every major advance in physics for more than a century has turned on

It’s not an exaggeration to say that every major advance in physics for more than a century has turned on  When I’m driving my car, I feel like I’m in my own private domicile, bitch! I’m the driver, so I’m in control: I choose the music, the temperature level, how fast or slow we go. I also suffer the consequences, but that’s fine—it’s my life! And yes, there are things I should consider—agreements between us, called ‘road rules’ and ‘traffic laws’—but if I disregard them, I can pretend that I’m the queen of my own little castle. So, vroom fucking vroom, baby! Let’s ride.

When I’m driving my car, I feel like I’m in my own private domicile, bitch! I’m the driver, so I’m in control: I choose the music, the temperature level, how fast or slow we go. I also suffer the consequences, but that’s fine—it’s my life! And yes, there are things I should consider—agreements between us, called ‘road rules’ and ‘traffic laws’—but if I disregard them, I can pretend that I’m the queen of my own little castle. So, vroom fucking vroom, baby! Let’s ride. Imagine if you went outside and saw that it had started to rain, and that people on the street were opening their umbrellas. And imagine that you ran around waving your arms and saying “Stop! Stop! Umbrellas make rain worse!!” People would think you were a silly person, and rightly so.

Imagine if you went outside and saw that it had started to rain, and that people on the street were opening their umbrellas. And imagine that you ran around waving your arms and saying “Stop! Stop! Umbrellas make rain worse!!” People would think you were a silly person, and rightly so.

Sharanya Deepak in The Baffler:

Sharanya Deepak in The Baffler:

Ewald Engelen in Sidecar:

Ewald Engelen in Sidecar: I

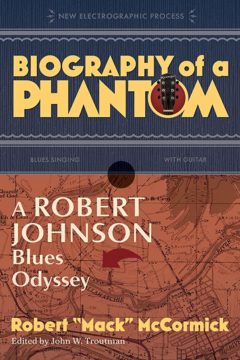

I The Robert Johnson we meet in this book remains somewhat blurry and indistinct. He wasn’t a big personality, people tell McCormick. He was soft-spoken; he held people’s attention only when he played.

The Robert Johnson we meet in this book remains somewhat blurry and indistinct. He wasn’t a big personality, people tell McCormick. He was soft-spoken; he held people’s attention only when he played. One of the stultifying but ultimately true maxims of the analytics movement in sports says that most narratives around player performance are lies. Each player has a “

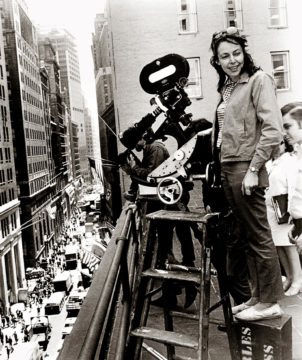

One of the stultifying but ultimately true maxims of the analytics movement in sports says that most narratives around player performance are lies. Each player has a “ Those who don’t already admire Hardwick’s writing likely know her from her marriage to poet Robert Lowell. It is at times a lurid story. A masterful poet, Lowell was also bipolar at a time when treatment was (as it still can be for many) uncertain and inconsistent. During manic episodes, he could be cruel to his wife. (“Everybody has noticed that you’ve been getting pretty dumb lately,” he told her during one episode.) While she worked to keep their household together, ensure bills were paid, and oversee his care, he would call her family to tell them he never loved her. His mania often coincided with brazen affairs; friends, colleagues, and even doctors sometimes suspected Hardwick of jealousy when she tried to get him help. When he finally left her after 20 years of marriage, he wrote a collection of poems—dedicated to his new wife, Caroline Blackwood—that excerpted his ex-wife’s plaintive letters to him and (perhaps the worse betrayal) fabricated others without noting the difference. The Dolphin was condemned by friends like Elizabeth Bishop and Adrienne Rich, but it also won the National Book Award. (In a published review, Rich called the book “one of the most vindictive and mean-spirited acts in the history of poetry.”) Years later, Lowell and Hardwick reconciled. Visiting her in New York not long after, he took a taxi from the airport and died before arriving. Summoned by the cab driver, Hardwick rode alongside Lowell to the hospital, knowing that he was already dead.

Those who don’t already admire Hardwick’s writing likely know her from her marriage to poet Robert Lowell. It is at times a lurid story. A masterful poet, Lowell was also bipolar at a time when treatment was (as it still can be for many) uncertain and inconsistent. During manic episodes, he could be cruel to his wife. (“Everybody has noticed that you’ve been getting pretty dumb lately,” he told her during one episode.) While she worked to keep their household together, ensure bills were paid, and oversee his care, he would call her family to tell them he never loved her. His mania often coincided with brazen affairs; friends, colleagues, and even doctors sometimes suspected Hardwick of jealousy when she tried to get him help. When he finally left her after 20 years of marriage, he wrote a collection of poems—dedicated to his new wife, Caroline Blackwood—that excerpted his ex-wife’s plaintive letters to him and (perhaps the worse betrayal) fabricated others without noting the difference. The Dolphin was condemned by friends like Elizabeth Bishop and Adrienne Rich, but it also won the National Book Award. (In a published review, Rich called the book “one of the most vindictive and mean-spirited acts in the history of poetry.”) Years later, Lowell and Hardwick reconciled. Visiting her in New York not long after, he took a taxi from the airport and died before arriving. Summoned by the cab driver, Hardwick rode alongside Lowell to the hospital, knowing that he was already dead. May, by contrast, the elusive

May, by contrast, the elusive