Category: Recommended Reading

Why do mass shooters kill?

Arie Kruglanski in The Conversation:

The year 2023 is still young, and already there have been at least 146 mass shooting events in the U.S. on record, including the killing of five people in a Louisville, Kentucky, bank that the shooter livestreamed. There were 647 mass shootings in 2022 and 693 in 2021, resulting in 859 and 920 deaths, respectively, with no respite in sight from this ghastly epidemic. Since 2015, over 19,000 people have been shot and wounded or killed in mass shootings.

The year 2023 is still young, and already there have been at least 146 mass shooting events in the U.S. on record, including the killing of five people in a Louisville, Kentucky, bank that the shooter livestreamed. There were 647 mass shootings in 2022 and 693 in 2021, resulting in 859 and 920 deaths, respectively, with no respite in sight from this ghastly epidemic. Since 2015, over 19,000 people have been shot and wounded or killed in mass shootings.

In the wake of most shootings, the news media and the public reflexively ask: What was the killer’s motive?

As a psychologist who studies violence and extremism, I understand that the question immediately pops to mind because of the bizarre nature of the attacks, the “out-of-the-blue” shock that they produce, and people’s need to comprehend and reach closure on what initially appears to be completely senseless and irrational. But what would constitute a satisfactory answer to the public’s question?

More here.

“But Where’s Its Anus?”: On Alien Lifeforms

Jaime Green at LitHub:

I first read Carl Sagan’s Contact and Cosmos in high school, when I was working at a bookstore that let us borrow any book we had at least two copies of on the shelves. I loved them then and was excited to revisit these books in the course of my research for The Possibility of Life. A scene from Cosmos had stayed with me—and confounded me—for almost twenty years, and I was ready to make new sense of it. But when I got to the place in the book where the scene should have been, the chapter just ended.

I first read Carl Sagan’s Contact and Cosmos in high school, when I was working at a bookstore that let us borrow any book we had at least two copies of on the shelves. I loved them then and was excited to revisit these books in the course of my research for The Possibility of Life. A scene from Cosmos had stayed with me—and confounded me—for almost twenty years, and I was ready to make new sense of it. But when I got to the place in the book where the scene should have been, the chapter just ended.

Luckily, I was reading an e-book, so I could search anus… Zero results.

Let me explain.

The scene I remembered is in a classroom—I don’t know if Sagan was teacher or student—and the class is split into groups, each tasked with designing an alien life-form. The professor looks at their anatomy sketches and chides, “Where’s its anus?” What had haunted me across the decades was my confusion: Was the professor closed-minded, or were the students being careless?

more here.

Philip Roth Unbound

Simone Giertz: Queen of Shitty Robots

US could soon approve MDMA therapy — opening an era of psychedelic medicine

Sara Reardon in Nature:

For Rick Doblin, 2023 could be a landmark year: the year that the US government decides whether it will allow the use of hallucinogenic drugs to treat mental illness.

For Rick Doblin, 2023 could be a landmark year: the year that the US government decides whether it will allow the use of hallucinogenic drugs to treat mental illness.

Doblin, who is based in Belmont, Massachusetts, is the founder and president of the non-profit organization Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS). He has spent nearly 40 years researching whether the experience produced by the psychedelic drug MDMA — also called ecstasy or molly — can help people with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In 2021, MAPS’s phase III clinical trial of 90 people with PTSD found that those who received MDMA coupled with psychotherapy were twice as likely to recover from the condition as were those who received psychotherapy with a placebo1 (see ‘Response to MDMA therapy’).

More here.

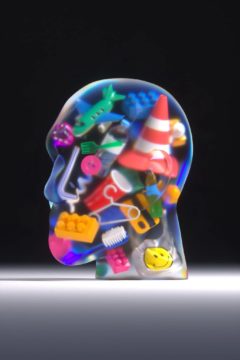

There Is Plastic in Our Flesh

Mark O’Connell in The New York Times:

There is plastic in our bodies; it’s in our lungs and our bowels and in the blood that pulses through us. We can’t see it, and we can’t feel it, but it is there. It is there in the water we drink and the food we eat, and even in the air that we breathe. We don’t know, yet, what it’s doing to us, because we have only quite recently become aware of its presence; but since we have learned of it, it has become a source of profound and multifarious cultural anxiety.

There is plastic in our bodies; it’s in our lungs and our bowels and in the blood that pulses through us. We can’t see it, and we can’t feel it, but it is there. It is there in the water we drink and the food we eat, and even in the air that we breathe. We don’t know, yet, what it’s doing to us, because we have only quite recently become aware of its presence; but since we have learned of it, it has become a source of profound and multifarious cultural anxiety.

Maybe it’s nothing; maybe it’s fine. Maybe this jumble of fragments — bits of water bottles, tires, polystyrene packaging, microbeads from cosmetics — is washing through us and causing no particular harm. But even if that were true, there would still remain the psychological impact of the knowledge that there is plastic in our flesh. This knowledge registers, in some vague way, as apocalyptic; it has the feel of a backhanded divine vengeance, sly and poetically appropriate. Maybe this has been our fate all along, to achieve final communion with our own garbage.

More here.

Thursday Poem

This, in my imagination, is the moment Robert Burns

turns to the life of poetry. —Nils Peterson

A Kind of Biography

All night the language dog

gnaws at the meaning bone.

Soon the sea begins

to question its shuffling

from East to West, and the stars

their vast, ordinary circuits.

So my friend has fled into his father’s fields.

He leans against a fence

and wonders what the ant means

and the moonlight grasses as they bend

and spread and flow beneath

a wind whose beginning seems obscure

and whose end, uncertain.

He notices that something of himself

has set off with the wind

and that he is now two.

He wonders at his doubleness.

Back home, he sits in the kitchen,

an ordinary boy watching

his mother cook breakfast,

but something of him is in

another place, and some other thing

Is with him even here.

by Nils Peterson

from The Dear Time of Our Talking

Frog On The Moon Press, 2020

Wednesday, April 19, 2023

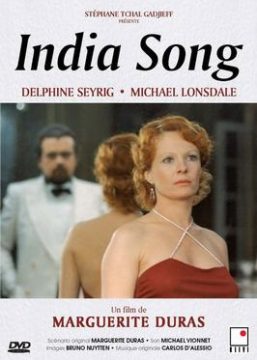

In the Thrall of Duras

Ivone Margulies at The Current:

Marguerite Duras’s India Song is a hypnotic chant d’amour, a release system for the author’s polyphonic writing, and one of the most beautiful films in cinema history. In its extended central scene, at a French Embassy reception in Calcutta, four Cerruti 1881–clad men dance with and flit around a beguiling red-haired woman (Delphine Seyrig). Mesmerized, we join an unseen audience that speaks for and about these characters as they glide silently into the realm of legend. Filled with haunting rumbas and pierced by scandalous cries, this mirrored salon and its ghosts stay with us long after the film’s end.

Marguerite Duras’s India Song is a hypnotic chant d’amour, a release system for the author’s polyphonic writing, and one of the most beautiful films in cinema history. In its extended central scene, at a French Embassy reception in Calcutta, four Cerruti 1881–clad men dance with and flit around a beguiling red-haired woman (Delphine Seyrig). Mesmerized, we join an unseen audience that speaks for and about these characters as they glide silently into the realm of legend. Filled with haunting rumbas and pierced by scandalous cries, this mirrored salon and its ghosts stay with us long after the film’s end.

Upon its release in 1975, Duras’s tale of doomed passion defied conventional cinema with its antinaturalist aesthetic, anachronistic setting, and unrepentantly Romantic stance. With its glamorous and compact theatricality, Duras’s work shared with her contemporaries Jacques Rivette, Manoel de Oliveira, and Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet a disregard for generic borders.

more here.

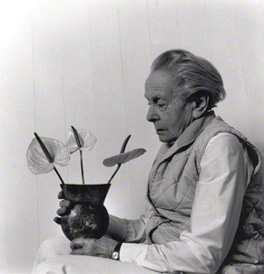

The Groundbreaking Art Of Lucie Rie

Ali Smith at The New Statesman:

On yet another of the many days we’re living through in which our government sends out poisonous, divisive and powermongering rhetoric about disallowing entry in the UK to refugees, especially those endangered people brave enough to arrive in small boats, I went to see the Lucie Rie exhibition, “The Adventure of Pottery”, at Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge. Rie, an international prizewinner when she was only in her thirties, had been ploughing an original furrow against the grain of ceramic design expectations in Vienna in the 1930s. She trained at the city’s Kunstgewerbeschule but made work like no one else, based on her own experiments on ancient Roman pots she’d seen in the vineyard of an uncle, and in her determination to make and use glazes her tutor had told her were impossible.

She arrived in England from Vienna as an Austrian Jewish fugitive from Hitler’s fascism in 1938 with a suitcase full of the pots she’d made wrapped in her clothes.

more here.

The Ceramic Presence in Modern Art

Revisiting Bruno Schulz

Leo Lasdun in The Millions:

In Humboldt’s Gift, Saul Bellow’s roman à clef about his turbulent friendship with the poet Delmore Schwartz, the Bellow stand-in muses that “all the highly gifted see themselves shunted for decades onto dull sidings, banished exiled nailed up in chicken coops. Imagination has even tried to surmount the problems by forcing boredom itself to yield interest.” He goes on to name Joyce, Stendhal, Flaubert, and Baudelaire as a few sultans of solitude. If he’d wanted to sell it even harder, he might have tacked on the Jewish-Polish writer and artist Bruno Schulz. Unearthed again in a new biography by Benjamin Balint, Schulz was hamstrung by boredom and loneliness. Twice denied a paid leave of absence (which he requested in order to focus on his writing) from his job as a school teacher, and later boxed into a Jewish ghetto, Schulz spent nearly his entire life in Drohobycz, where he was born in 1892. The small slippery city has changed management a number of times: for most of Schulz’s adulthood, Drohobycz was part of Poland, before that Austria-Hungary, now it’s part of Ukraine (spelled Drohobych). Except for some short trips, Schulz never left his hometown, and he became well acquainted with isolation. In his own words, “loneliness is the catalyst that makes reality ferment”; in Balint’s words, Schulz “made of his solitude a way of seeing.”

In Humboldt’s Gift, Saul Bellow’s roman à clef about his turbulent friendship with the poet Delmore Schwartz, the Bellow stand-in muses that “all the highly gifted see themselves shunted for decades onto dull sidings, banished exiled nailed up in chicken coops. Imagination has even tried to surmount the problems by forcing boredom itself to yield interest.” He goes on to name Joyce, Stendhal, Flaubert, and Baudelaire as a few sultans of solitude. If he’d wanted to sell it even harder, he might have tacked on the Jewish-Polish writer and artist Bruno Schulz. Unearthed again in a new biography by Benjamin Balint, Schulz was hamstrung by boredom and loneliness. Twice denied a paid leave of absence (which he requested in order to focus on his writing) from his job as a school teacher, and later boxed into a Jewish ghetto, Schulz spent nearly his entire life in Drohobycz, where he was born in 1892. The small slippery city has changed management a number of times: for most of Schulz’s adulthood, Drohobycz was part of Poland, before that Austria-Hungary, now it’s part of Ukraine (spelled Drohobych). Except for some short trips, Schulz never left his hometown, and he became well acquainted with isolation. In his own words, “loneliness is the catalyst that makes reality ferment”; in Balint’s words, Schulz “made of his solitude a way of seeing.”

More here.

Sean Carroll’s Mindscape Podcast: Hugo Mercier on Reasoning and Skepticism

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

Here at the Mindscape Podcast, we are firmly pro-reason. But what does that mean, fundamentally and in practice? How did humanity come into the idea of not just doing things, but doing things for reasons? In this episode we talk with cognitive scientist Hugo Mercier about these issues. He is the co-author (with Dan Sperber) of The Enigma of Reason, about how the notion of reason came to be, and more recently author of Not Born Yesterday, about who we trust and what we believe. He argues that our main shortcoming is not being insufficiently skeptical of radical claims, but of being too skeptical of claims that don’t fit our views.

Here at the Mindscape Podcast, we are firmly pro-reason. But what does that mean, fundamentally and in practice? How did humanity come into the idea of not just doing things, but doing things for reasons? In this episode we talk with cognitive scientist Hugo Mercier about these issues. He is the co-author (with Dan Sperber) of The Enigma of Reason, about how the notion of reason came to be, and more recently author of Not Born Yesterday, about who we trust and what we believe. He argues that our main shortcoming is not being insufficiently skeptical of radical claims, but of being too skeptical of claims that don’t fit our views.

More here.

Feudalism by Design: On Quinn Slobodian’s “Crack-Up Capitalism”

Jodi Dean at the Los Angeles Review of Books:

At a rally in 2019, California Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon announced, “When you hear about folks talking about the new economy, the gig economy, the innovation economy, it’s fucking feudalism all over again.” Rendon was there to support legislation classifying most gig workers as employees rather than independent contractors. Assembly Bill 5 was intended to bring gig workers under the protection of existing California labor laws, and the bill passed. But the following year, California voters chose feudalism: they approved Proposition 22, a ballot measure heavily funded by Uber, Lyft, DoorDash, and Instacart, that would exempt app-based drivers from the labor protections that Assembly Bill 5 tried to secure. In March 2023, a state appellate court upheld Prop 22. By making exceptions for the big transportation and delivery apps, by saying that employment laws do not apply to them, California is entrenching the labor relations—the feudalism—that Rendon warned against.

At a rally in 2019, California Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon announced, “When you hear about folks talking about the new economy, the gig economy, the innovation economy, it’s fucking feudalism all over again.” Rendon was there to support legislation classifying most gig workers as employees rather than independent contractors. Assembly Bill 5 was intended to bring gig workers under the protection of existing California labor laws, and the bill passed. But the following year, California voters chose feudalism: they approved Proposition 22, a ballot measure heavily funded by Uber, Lyft, DoorDash, and Instacart, that would exempt app-based drivers from the labor protections that Assembly Bill 5 tried to secure. In March 2023, a state appellate court upheld Prop 22. By making exceptions for the big transportation and delivery apps, by saying that employment laws do not apply to them, California is entrenching the labor relations—the feudalism—that Rendon warned against.

More here.

Max Tegmark interview: Six months to save humanity from AI?

7 ways teachers can use Chat Gpt in the classroom!

From History4Humans:

I got to admit, when I pictured the robots 🤖 coming, I didn’t think they’d be here to do our students’ homework and write their essays, but that day has arrived! Many schools and districts around the country have already put the site behind a firewall but trust me, the cat is out of the bag and its not going back in! I do not think that is the right call and I think we must get ahead of this instead of trying to ineffectually sweep it under the rug. So, I wanted to write a little article about how teachers can use Chat GPT in the classroom. So, if you don’t know, CHATGPT is an AI software (currently free to use though that might change soon) that can do a ton of writing tasks when given commands. Students can use chatgpt to ask questions and receive answers or to generate entire written assignments based on any prompt.

I got to admit, when I pictured the robots 🤖 coming, I didn’t think they’d be here to do our students’ homework and write their essays, but that day has arrived! Many schools and districts around the country have already put the site behind a firewall but trust me, the cat is out of the bag and its not going back in! I do not think that is the right call and I think we must get ahead of this instead of trying to ineffectually sweep it under the rug. So, I wanted to write a little article about how teachers can use Chat GPT in the classroom. So, if you don’t know, CHATGPT is an AI software (currently free to use though that might change soon) that can do a ton of writing tasks when given commands. Students can use chatgpt to ask questions and receive answers or to generate entire written assignments based on any prompt.

I actually just had it write out a screen play for President Washington meeting with his cabinet to discuss the constitutionality of the Bank except it was a Seinfeld episode and it was pretty funny while still having Jefferson opposed to the Bank, Washington neutral at first, and Hamilton in support. (Jefferson, as Kramer wanted to use a cardboard box with some gold coins instead of a national bank 🤣).

But seriously, this has many teachers (and tons of other professions) freaking out.

Is it the end of homework? The takehome essay? Critical thinking?

NOPE!

More here.

Sometimes painted with a single eyelash, Willard Wigan’s tiny sculptures fit in the eye of a needle

Julia Binswanger in Smithsonian:

Artist Willard Wigan is famous for his recreations of famous paintings like the Mona Lisa and The Last Supper, as well his depictions of famous figures like William Shakespeare and Robin Hood. But in order to view them, you’ll need a microscope. Wigan’s new show, “Miniature Masterpieces,” is currently on display at Wollaton Hall in Nottingham, England. The free exhibition features 20 tiny sculptures, each of which sits in the eye of a needle.

Artist Willard Wigan is famous for his recreations of famous paintings like the Mona Lisa and The Last Supper, as well his depictions of famous figures like William Shakespeare and Robin Hood. But in order to view them, you’ll need a microscope. Wigan’s new show, “Miniature Masterpieces,” is currently on display at Wollaton Hall in Nottingham, England. The free exhibition features 20 tiny sculptures, each of which sits in the eye of a needle.

“This is more complicated than any microsurgery,” Wigan tells Wired in a video interview. “I don’t care what anybody says. You have to have a more stable hand than any surgeon to do this work.” Perhaps this sounds like an exaggeration, but careless mistakes can put an end to weeks of progress. Once, after finishing a sculpture depicting a scene from Alice in Wonderland, Wigan’s phone rang. “I went, ‘Who’s that?’ And as I breathed in, I inhaled Alice,” he tells Wired. “Gone. Somewhere in my cavities.”

More here.

Wednesday Poem

Believe, Believe

Believe in this. Young apple seeds,

In blue skies, radiating young breast,

Not in blue-suited insects,

Infesting society’s garments.

Believe in the swinging sounds of jazz,

Tearing the night into intricate shreds,

Putting it back together again,

In cool logical patterns,

Not in the sick controllers,

Who created only the Bomb.

Let the voices of dead poets

Ring louder in your ears

Than the screechings mouthed

In mildewed editorials.

Listen to the music of centuries,

Rising above the mushroom time

By Bob Kaufman

from Cranial Guitar

Coffee House Press, 1996

Tuesday, April 18, 2023

A life of splendid uselessness is a life well lived

Joseph M Keegin in Psyche:

Great art and thought have always been motivated by something other than mere moneymaking, even if moneymaking happened somewhere along the way. But our culture of instrumentality has settled like a thick fog over the idea that some activities are worth pursuing simply because they share in the beautiful, the good, or the true. No amount of birdwatching will win a person the presidency or a Beverly Hills mansion; making music with friends will not cure cancer or establish a colony on Mars. But the real project of humanity – of understanding ourselves as human beings, making a good world to live in, and striving together toward mutual flourishing – depends paradoxically upon the continued pursuit of what Hitz calls ‘splendid uselessness’.

Great art and thought have always been motivated by something other than mere moneymaking, even if moneymaking happened somewhere along the way. But our culture of instrumentality has settled like a thick fog over the idea that some activities are worth pursuing simply because they share in the beautiful, the good, or the true. No amount of birdwatching will win a person the presidency or a Beverly Hills mansion; making music with friends will not cure cancer or establish a colony on Mars. But the real project of humanity – of understanding ourselves as human beings, making a good world to live in, and striving together toward mutual flourishing – depends paradoxically upon the continued pursuit of what Hitz calls ‘splendid uselessness’.

The culture of the 21st century – on an increasingly planetary scale – is oriented around the practical principles of utility, effectiveness and impact. The worth of anything – an idea, an activity, an artwork, a relationship with another person – is determined pragmatically: things are good to the extent that they are instrumental, with instrumentality usually defined as the capacity to produce money or things.

More here.

Are coincidences real?

Paul Broks in The Guardian:

The biography of the actor Anthony Hopkins contains a striking example of a serendipitous coincidence. When he first heard he’d been cast to play a part in the film The Girl from Petrovka (1974), Hopkins went in search of a copy of the book on which it was based, a novel by George Feifer. He combed the bookshops of London in vain and, somewhat dejected, gave up and headed home. Then, to his amazement, he spotted a copy of The Girl from Petrovka lying on a bench at Leicester Square station. He recounted the story to Feifer when they met on location, and it transpired that the book Hopkins had stumbled upon was the very one that the author had mislaid in another part of London – an advance copy full of red-ink amendments and marginal notes he’d made in preparation for a US edition.

The biography of the actor Anthony Hopkins contains a striking example of a serendipitous coincidence. When he first heard he’d been cast to play a part in the film The Girl from Petrovka (1974), Hopkins went in search of a copy of the book on which it was based, a novel by George Feifer. He combed the bookshops of London in vain and, somewhat dejected, gave up and headed home. Then, to his amazement, he spotted a copy of The Girl from Petrovka lying on a bench at Leicester Square station. He recounted the story to Feifer when they met on location, and it transpired that the book Hopkins had stumbled upon was the very one that the author had mislaid in another part of London – an advance copy full of red-ink amendments and marginal notes he’d made in preparation for a US edition.

More here. [And here’s a coincidence I wrote about at 3QD some years ago.]