Anil Ananthaswamy in Quanta:

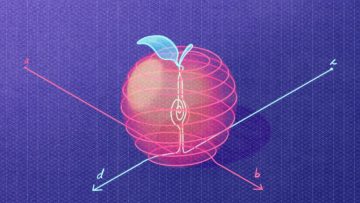

The key is that each piece of information, such as the notion of a car, or its make, model or color, or all of it together, is represented as a single entity: a hyperdimensional vector.

The key is that each piece of information, such as the notion of a car, or its make, model or color, or all of it together, is represented as a single entity: a hyperdimensional vector.

A vector is simply an ordered array of numbers. A 3D vector, for example, comprises three numbers: the x, y and z coordinates of a point in 3D space. A hyperdimensional vector, or hypervector, could be an array of 10,000 numbers, say, representing a point in 10,000-dimensional space. These mathematical objects and the algebra to manipulate them are flexible and powerful enough to take modern computing beyond some of its current limitations and foster a new approach to artificial intelligence.

“This is the thing that I’ve been most excited about, practically in my entire career,” Olshausen said. To him and many others, hyperdimensional computing promises a new world in which computing is efficient and robust, and machine-made decisions are entirely transparent.

More here.

To most people today, the notion of a leisure ethic will sound foreign, paradoxical, and indeed subversive, even though leisure is still commonly associated with the good life. More than any other society in the past, ours certainly has the technology and the wealth to furnish more people with greater freedom over more of their time. Yet because we lack a shared leisure ethic, we have not availed ourselves of that option. Nor does it occur to us even to demand or strive for such a dispensation.

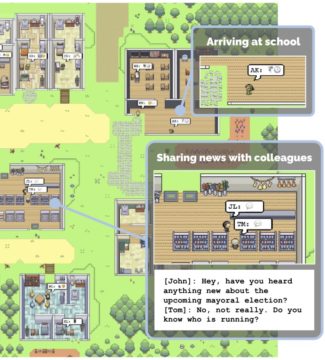

To most people today, the notion of a leisure ethic will sound foreign, paradoxical, and indeed subversive, even though leisure is still commonly associated with the good life. More than any other society in the past, ours certainly has the technology and the wealth to furnish more people with greater freedom over more of their time. Yet because we lack a shared leisure ethic, we have not availed ourselves of that option. Nor does it occur to us even to demand or strive for such a dispensation. The researchers found that their agents could “produce believable individual and emergent social behaviors.” For instance, one agent attempted to throw a Valentine’s Day party by sending out invites and setting a time and place for the party.

The researchers found that their agents could “produce believable individual and emergent social behaviors.” For instance, one agent attempted to throw a Valentine’s Day party by sending out invites and setting a time and place for the party. The thought of adding crickets to a summer gazpacho or making your tacos out of honey bee moths is likely to make the majority of us squirm. But faced with a future of growing food scarcity, insects may soon become a kitchen staple; a regular ingredient in our everyday cooking. In Beatle in the box, Italian photographers Michela Benaglia and Emanuela Colombo combine various genres such as still life and food photography in a bid to normalize this fact visually. Rich with proteins, vitamins, carbs, omega-3 fatty acids, calcium, iron and other micronutrients, bugs and beasties have a low environmental-impact as food. They are small, meaning they cause less greenhouse gasses which is an important factor in livestock farming, and they can also be bred easily with few resources. In short, they might be the food of our future. The photographers propose a handy comparison: the growth and spread of sushi through the West in the 1990s—first as a trend, then as a food business.

The thought of adding crickets to a summer gazpacho or making your tacos out of honey bee moths is likely to make the majority of us squirm. But faced with a future of growing food scarcity, insects may soon become a kitchen staple; a regular ingredient in our everyday cooking. In Beatle in the box, Italian photographers Michela Benaglia and Emanuela Colombo combine various genres such as still life and food photography in a bid to normalize this fact visually. Rich with proteins, vitamins, carbs, omega-3 fatty acids, calcium, iron and other micronutrients, bugs and beasties have a low environmental-impact as food. They are small, meaning they cause less greenhouse gasses which is an important factor in livestock farming, and they can also be bred easily with few resources. In short, they might be the food of our future. The photographers propose a handy comparison: the growth and spread of sushi through the West in the 1990s—first as a trend, then as a food business. Among the many unique experiences of reporting on A.I. is this: In a young industry flooded with hype and money, person after person tells me that they are desperate to be regulated, even if it slows them down. In fact, especially if it slows them down. What they tell me is obvious to anyone watching. Competition is forcing them to go too fast and cut too many corners. This technology is too important to be left to a race between Microsoft, Google, Meta and a few other firms. But no one company can slow down to a safe pace without risking irrelevancy. That’s where the government comes in — or so they hope.

Among the many unique experiences of reporting on A.I. is this: In a young industry flooded with hype and money, person after person tells me that they are desperate to be regulated, even if it slows them down. In fact, especially if it slows them down. What they tell me is obvious to anyone watching. Competition is forcing them to go too fast and cut too many corners. This technology is too important to be left to a race between Microsoft, Google, Meta and a few other firms. But no one company can slow down to a safe pace without risking irrelevancy. That’s where the government comes in — or so they hope. “They could never believe in a giant fish that holds a whole world. They’d laugh. They’d scoff. Even if they saw it, they wouldn’t believe it. That is why the human race is dying — too limited an imagination.”

“They could never believe in a giant fish that holds a whole world. They’d laugh. They’d scoff. Even if they saw it, they wouldn’t believe it. That is why the human race is dying — too limited an imagination.” A

A

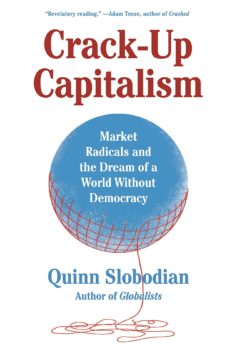

Lee Harris in The American Prospect:

Lee Harris in The American Prospect: Charlie Tyson in Jewish Currents:

Charlie Tyson in Jewish Currents: Jodi Dean in LA Review of Books:

Jodi Dean in LA Review of Books: One of the most useful metaphors for driving scientific and engineering progress has been that of the “machine.” But in light of our increased understanding of biology, evolution, intelligence, and engineering we must re-examine the life-as-machine metaphor with fair, up-to-date definitions. Such a process is allowing us to see that living things are in fact remarkable, agential, morally-important machines, writes Michael Levin.

One of the most useful metaphors for driving scientific and engineering progress has been that of the “machine.” But in light of our increased understanding of biology, evolution, intelligence, and engineering we must re-examine the life-as-machine metaphor with fair, up-to-date definitions. Such a process is allowing us to see that living things are in fact remarkable, agential, morally-important machines, writes Michael Levin. Relics of ancient viruses – that have spent millions of years hiding inside human DNA – help the body fight cancer, say scientists. The study by the Francis Crick Institute showed the dormant remnants of these old viruses are woken up when cancerous cells spiral out of control. This unintentionally helps the immune system target and attack the tumour. The team wants to harness the discovery to design vaccines that can boost cancer treatment, or even prevent it. The researchers had noticed a connection between better survival from lung cancer and a part of the immune system, called B-cells, clustering around tumours.

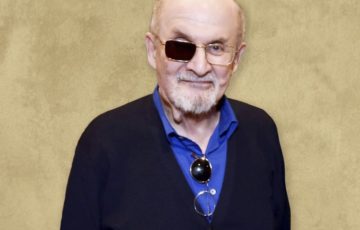

Relics of ancient viruses – that have spent millions of years hiding inside human DNA – help the body fight cancer, say scientists. The study by the Francis Crick Institute showed the dormant remnants of these old viruses are woken up when cancerous cells spiral out of control. This unintentionally helps the immune system target and attack the tumour. The team wants to harness the discovery to design vaccines that can boost cancer treatment, or even prevent it. The researchers had noticed a connection between better survival from lung cancer and a part of the immune system, called B-cells, clustering around tumours. Salman Rushdie

Salman Rushdie