From Phys.Org:

A George Washington University study offers new insights into why human cultures become more complex over time. The study finds that people combine and generalize socially acquired knowledge over time, resulting in new and more complex knowledge. The ability to combine and generalize socially learned knowledge appears to occur prior to formal schooling and may represent a unique feature of human intelligence called generative cultural learning.

A George Washington University study offers new insights into why human cultures become more complex over time. The study finds that people combine and generalize socially acquired knowledge over time, resulting in new and more complex knowledge. The ability to combine and generalize socially learned knowledge appears to occur prior to formal schooling and may represent a unique feature of human intelligence called generative cultural learning.

A team from GW’s Social Cognition Lab, led by associate professor Francys Subiaul, assigned preschool-age children and college-age adults to build a tower by stacking two cubes, linking two flat squares, and then combining the two components. In a previous study, none of the preschool-age children and only 5% of adults provided with cubes and squares had produced the optimal tower on their own. However, after observing a model stack cubes and another model link squares, over 40% of children and 75% of adults imitated the demonstrated actions and built an optimal tower. The current study replicated the methods used in the previous study, but provided participants with twice as many cubes and squares. Not only did the participants use the social knowledge provided and extend it to the new exercise, they also spontaneously combined these two newly developed responses with additional cubes and squares to form one new, extra-tall tower. Although adults were better at the task overall, both children and adults learned at equivalent rates and made similar errors.

“The similarity of performance between children and adults, despite the wide gulf in experience, offers powerful evidence that these skills are neither learned in school nor explicitly taught by caretakers,” Subiaul said. “Instead, this mode of social learning involving the combination and generalization of social knowledge appears to be done by default. These results provide compelling evidence as to why only human cultures evolve and become increasingly complex over time.”

More here.

In recent years we have heard much about The Five, the spiritualist group of women—af Klint, Cassel, Cornelia Cederberg, Sigrid Hedman, and Mathilda Nilsson—who channeled messages from “higher powers” from 1897 to 1907. A gifted medium, Cassel would eventually come to dominate the group, while af Klint played a more subsidiary role. It was working together outside of this quintet, however, that af Klint and Cassel each began to receive messages from the spirit realms asking for their participation in a “special mission.” The ensuing visual collaboration resulted in numerous preliminary sketches and twenty-seven small oil paintings executed between October 1906 and September 1907; this is the inaugural series of “The Paintings for the Temple” and thus a crucial juncture in the history of abstraction. Titled “Series I” or “The First 26 Small Ones” (the title would be changed later to “Primordial Chaos”), this body of work endeavored to visualize the so-called Akashic records: a supernatural compendium, as elucidated by Theosophy’s cofounder and chief theoretician, Helena Blavatsky, of all universal events and thoughts occurring in the past, present, and future and concerning all life forms. Analyzing the works in Cassel’s notebooks, Martin has convincingly been able to parcel out fourteen works belonging to her in this series and includes two comparisons that illustrate the women’s different styles. Cassel paid greater attention to detail, for example, and her application of paint was more careful and smoother than af Klint’s expressive surfaces, resulting in a deeper saturation of color.

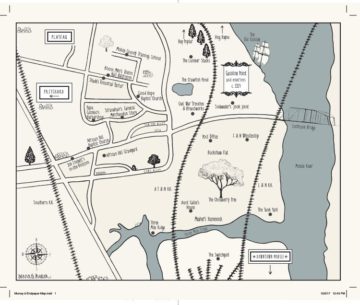

In recent years we have heard much about The Five, the spiritualist group of women—af Klint, Cassel, Cornelia Cederberg, Sigrid Hedman, and Mathilda Nilsson—who channeled messages from “higher powers” from 1897 to 1907. A gifted medium, Cassel would eventually come to dominate the group, while af Klint played a more subsidiary role. It was working together outside of this quintet, however, that af Klint and Cassel each began to receive messages from the spirit realms asking for their participation in a “special mission.” The ensuing visual collaboration resulted in numerous preliminary sketches and twenty-seven small oil paintings executed between October 1906 and September 1907; this is the inaugural series of “The Paintings for the Temple” and thus a crucial juncture in the history of abstraction. Titled “Series I” or “The First 26 Small Ones” (the title would be changed later to “Primordial Chaos”), this body of work endeavored to visualize the so-called Akashic records: a supernatural compendium, as elucidated by Theosophy’s cofounder and chief theoretician, Helena Blavatsky, of all universal events and thoughts occurring in the past, present, and future and concerning all life forms. Analyzing the works in Cassel’s notebooks, Martin has convincingly been able to parcel out fourteen works belonging to her in this series and includes two comparisons that illustrate the women’s different styles. Cassel paid greater attention to detail, for example, and her application of paint was more careful and smoother than af Klint’s expressive surfaces, resulting in a deeper saturation of color. Circa 1969, the writer Albert Murray paid a visit to his hometown on the Alabama Gulf Coast, to report a story for Harper’s. Murray hadn’t lived there since 1935, the year he left for college. During his childhood, elements of heavy industry—sawmills, paper mills, an oil refinery—had always coexisted with wilderness, in the kind of eerily beautiful landscapes that are found only in bayou country. But as an adult, Murray was aghast to see how much industry had encroached. The “fabulous old sawmill-whistle territory, the boy-blue adventure country” of his childhood, he wrote, had been overtaken by a massive paper factory: a “storybook dragon disguised as a wide-sprawling, foul-smelling, smoke-chugging factory.” He imagined that the people who had died during his years away had been “victims of dragon claws.”

Circa 1969, the writer Albert Murray paid a visit to his hometown on the Alabama Gulf Coast, to report a story for Harper’s. Murray hadn’t lived there since 1935, the year he left for college. During his childhood, elements of heavy industry—sawmills, paper mills, an oil refinery—had always coexisted with wilderness, in the kind of eerily beautiful landscapes that are found only in bayou country. But as an adult, Murray was aghast to see how much industry had encroached. The “fabulous old sawmill-whistle territory, the boy-blue adventure country” of his childhood, he wrote, had been overtaken by a massive paper factory: a “storybook dragon disguised as a wide-sprawling, foul-smelling, smoke-chugging factory.” He imagined that the people who had died during his years away had been “victims of dragon claws.” Two hundred years ago, the poets and philosophers of the Romantic movement came to an intoxicating thought: art can express the otherwise inexpressible conditions that make everyday sense and experience possible. Art, the Romantics said, is our interface with the real patterns and relations that weave up the world of rational thought and perception. And, although most philosophers and artists today don’t profess to taking this idea very literally, I believe that not much in our current way of caring about literature and music, film and painting, dance and sculpture, works without it. My purpose here is to show that today’s first blushings of a mathematical viewpoint on pattern, mind and (human) world make the Romantic theory of art literally plausible.

Two hundred years ago, the poets and philosophers of the Romantic movement came to an intoxicating thought: art can express the otherwise inexpressible conditions that make everyday sense and experience possible. Art, the Romantics said, is our interface with the real patterns and relations that weave up the world of rational thought and perception. And, although most philosophers and artists today don’t profess to taking this idea very literally, I believe that not much in our current way of caring about literature and music, film and painting, dance and sculpture, works without it. My purpose here is to show that today’s first blushings of a mathematical viewpoint on pattern, mind and (human) world make the Romantic theory of art literally plausible. Dazzling intricacies of brain structure are revealed every day, but one of the most obvious aspects of brain wiring eludes neuroscientists. The nervous system is cross-wired, so that the left side of the brain controls the right half of the body and vice versa. Every doctor relies upon this fact in performing neurological exams, but when I asked my doctor last week why this should be, all I got was a shrug. So I asked

Dazzling intricacies of brain structure are revealed every day, but one of the most obvious aspects of brain wiring eludes neuroscientists. The nervous system is cross-wired, so that the left side of the brain controls the right half of the body and vice versa. Every doctor relies upon this fact in performing neurological exams, but when I asked my doctor last week why this should be, all I got was a shrug. So I asked  In

In  E

E In the movies, time travelers typically step inside a machine and—poof—disappear. They then reappear instantaneously among cowboys, knights or dinosaurs. What these films show is basically

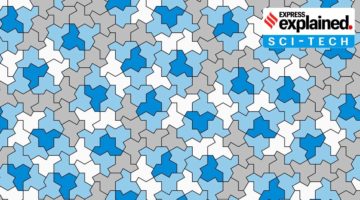

In the movies, time travelers typically step inside a machine and—poof—disappear. They then reappear instantaneously among cowboys, knights or dinosaurs. What these films show is basically  I won’t go into the history of the tiling problem here—Roberts does her typically clear, concise, and beguiling job in the article in question, well supplemented by an equally captivating account offered by longtime friend of the Cabinet, Margaret Wertheim, in a recent issue of her new substack Science Goddess, which you can find

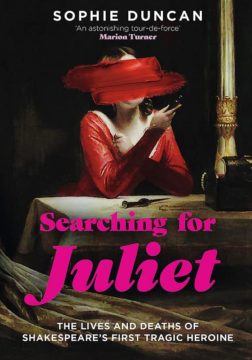

I won’t go into the history of the tiling problem here—Roberts does her typically clear, concise, and beguiling job in the article in question, well supplemented by an equally captivating account offered by longtime friend of the Cabinet, Margaret Wertheim, in a recent issue of her new substack Science Goddess, which you can find  In 1611, the Somerset-born traveller Thomas Coryat described an Italian architectural novelty: a ‘very pleasant little tarrasse, that jutteth or butteth out from the maine building: the edge whereof is decked with many pretty little turned pillers … to leane over’. England’s introduction to the balcony came over a decade after the first performance of William Shakespeare’s tragedy Romeo and Juliet. When it was staged in the summer of 1596, just before London’s playhouses were closed owing to a resurgence of plague, the exchange now universally known as the ‘balcony scene’ was probably transacted at a window opening onto the backstage ‘tiring house’ of the Shoreditch Theatre. The popular image of Juliet as a bright-eyed teenager in white muslin leaning over a balustrade only began to form a century and a half later, when a balcony first appeared as part of the stage set. By the late 1930s, the museum director Antonio Avena had improvised a ‘tarrasse’ from a marble sarcophagus and retrofitted it to the walls of Via Cappello 23 – putative home of the ‘historical’ Capulets in Verona. Visitors now pose on ‘Juliet’s balcony’ as part of an international pilgrimage that also includes visiting a bronze statue of Shakespeare’s heroine and rubbing her right breast for luck.

In 1611, the Somerset-born traveller Thomas Coryat described an Italian architectural novelty: a ‘very pleasant little tarrasse, that jutteth or butteth out from the maine building: the edge whereof is decked with many pretty little turned pillers … to leane over’. England’s introduction to the balcony came over a decade after the first performance of William Shakespeare’s tragedy Romeo and Juliet. When it was staged in the summer of 1596, just before London’s playhouses were closed owing to a resurgence of plague, the exchange now universally known as the ‘balcony scene’ was probably transacted at a window opening onto the backstage ‘tiring house’ of the Shoreditch Theatre. The popular image of Juliet as a bright-eyed teenager in white muslin leaning over a balustrade only began to form a century and a half later, when a balcony first appeared as part of the stage set. By the late 1930s, the museum director Antonio Avena had improvised a ‘tarrasse’ from a marble sarcophagus and retrofitted it to the walls of Via Cappello 23 – putative home of the ‘historical’ Capulets in Verona. Visitors now pose on ‘Juliet’s balcony’ as part of an international pilgrimage that also includes visiting a bronze statue of Shakespeare’s heroine and rubbing her right breast for luck. The novelist and screenwriter

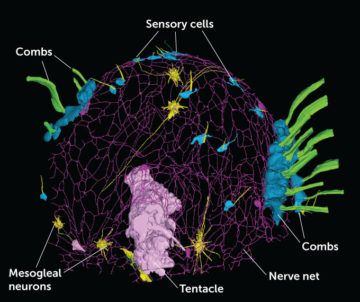

The novelist and screenwriter  Shimmering, gelatinous comb jellies wouldn’t appear to have much to hide. But their mostly see-through bodies cloak

Shimmering, gelatinous comb jellies wouldn’t appear to have much to hide. But their mostly see-through bodies cloak  Screentime limits

Screentime limits The researchers then observed how the birds used that newfound ability over a three-month period. They wondered: If given the choice, would the birds call each other?

The researchers then observed how the birds used that newfound ability over a three-month period. They wondered: If given the choice, would the birds call each other?