Cartoon Physics, part 1

Children under, say, ten, shouldn’t know

that the universe is ever-expanding,

inexorably pushing into the vacuum, galaxies

swallowed by galaxies, whole

solar systems collapsing, all of it

acted out in silence. At ten we are still learning

the rules of cartoon animation,

that if a man draws a door on a rock

only he can pass through it.

Anyone else who tries

will crash into the rock. Ten-year-olds

should stick with burning houses, car wrecks,

ships going down—earthbound, tangible

disasters, arenas

where they can be heroes. You can run

back into a burning house, sinking ships

have lifeboats, the trucks will come

with their ladders, if you jump

you will be saved. A child

places her hand on the roof of a schoolbus,

& drives across a city of sand. She knows

the exact spot it will skid, at which point

the bridge will give, who will swim to safety

& who will be pulled under by sharks. She will learn

that if a man runs off the edge of a cliff

he will not fall

until he notices his mistake.

by Nick Flynn

from: Some Ether.

Graywolf Press, 2000

Though many gaps in the story remain, the emerging evidence suggests clothing really had two origins: first for biological needs, then cultural. Archaeologists who study the Paleolithic or Stone Age

Though many gaps in the story remain, the emerging evidence suggests clothing really had two origins: first for biological needs, then cultural. Archaeologists who study the Paleolithic or Stone Age  On December 1, 2021, I tweeted: «Earlier this year I argued that we are living in a golden age of popular criticism. To prove my point … here’s the tip of the iceberg: my list of 21 of the best essays, reviews, and criticism published in 2021.»

On December 1, 2021, I tweeted: «Earlier this year I argued that we are living in a golden age of popular criticism. To prove my point … here’s the tip of the iceberg: my list of 21 of the best essays, reviews, and criticism published in 2021.» Beginning as early as the 1970s, astronomers noticed something funny going on with the galaxies in our nearby patch of the Universe. There was the usual and expected Hubble flow, the general recession of galaxies driven by the overall expansion of the Universe. But there seemed to be some vague directionality on top of that, as if all of the galaxies near us were also heading toward the same focal point.

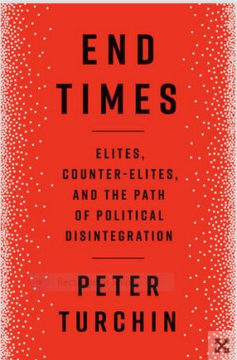

Beginning as early as the 1970s, astronomers noticed something funny going on with the galaxies in our nearby patch of the Universe. There was the usual and expected Hubble flow, the general recession of galaxies driven by the overall expansion of the Universe. But there seemed to be some vague directionality on top of that, as if all of the galaxies near us were also heading toward the same focal point. For almost two decades, Peter Turchin has been involved, with many colleagues and co-authors, in an epochal project: to figure out, using quantifiable evidence, what are the forces that lead to the rise, and more importantly, to the decline of nations, political turbulence and decay, and revolutions. This has resulted in the creation of an enormous database (CrisisDB) covering multitude of nations and empires over centuries, and several volumes of Turchin’s writings (e.g.,

For almost two decades, Peter Turchin has been involved, with many colleagues and co-authors, in an epochal project: to figure out, using quantifiable evidence, what are the forces that lead to the rise, and more importantly, to the decline of nations, political turbulence and decay, and revolutions. This has resulted in the creation of an enormous database (CrisisDB) covering multitude of nations and empires over centuries, and several volumes of Turchin’s writings (e.g.,  T

T Describe your ideal reading experience (when, where, what, how).

Describe your ideal reading experience (when, where, what, how). They told me they couldn’t offer me an interview with her at this time. Fine by me—I didn’t want to talk to her anyway. She talks a lot and doesn’t say much. A Financial Times profile published on the occasion of her fiftieth birthday suggested we have her to thank for spirulina, celebrity skin care lines, the good divorce, blended families, sex positivity, and dry skin brushing (just what it sounds like). I’ve also heard she made yoga happen. This is all obviously ridiculous, flatly ahistorical, except maybe the celebrity skin care line thing, but that doesn’t matter—even if someone thinks she’s done more harm than good, and that a lot of it is an upscale scam, they will comment, wearily, pragmatically, just a little bit enviously, that you have to respect it, don’t you, what she’s done. She has successfully integrated her imperial wellness company into American life. Memories of a time when gut health wasn’t something you discussed at parties are distant. Moms are microdosing. Vulnerability reigns. The countervailing spirit of resistance to quackery and “fake news” that characterized the Trump era is over, and eggs made of jade that you’re supposed to put in your vagina are still for sale. Everybody knows about the vagina eggs. The elderly know about them. People from Belgium know about them. What comes next, epochally, is still unclear. In the meantime, she has been, for some reason, partnering with a cruise line.

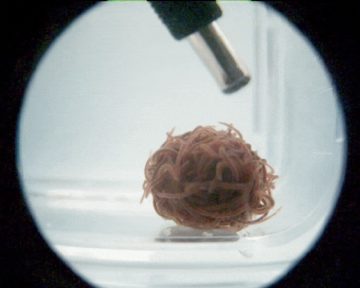

They told me they couldn’t offer me an interview with her at this time. Fine by me—I didn’t want to talk to her anyway. She talks a lot and doesn’t say much. A Financial Times profile published on the occasion of her fiftieth birthday suggested we have her to thank for spirulina, celebrity skin care lines, the good divorce, blended families, sex positivity, and dry skin brushing (just what it sounds like). I’ve also heard she made yoga happen. This is all obviously ridiculous, flatly ahistorical, except maybe the celebrity skin care line thing, but that doesn’t matter—even if someone thinks she’s done more harm than good, and that a lot of it is an upscale scam, they will comment, wearily, pragmatically, just a little bit enviously, that you have to respect it, don’t you, what she’s done. She has successfully integrated her imperial wellness company into American life. Memories of a time when gut health wasn’t something you discussed at parties are distant. Moms are microdosing. Vulnerability reigns. The countervailing spirit of resistance to quackery and “fake news” that characterized the Trump era is over, and eggs made of jade that you’re supposed to put in your vagina are still for sale. Everybody knows about the vagina eggs. The elderly know about them. People from Belgium know about them. What comes next, epochally, is still unclear. In the meantime, she has been, for some reason, partnering with a cruise line. Anyone who’s grappled with jumbled headphones knows the difficulty of disentangling snarled cords. A tight knot is nothing for a California blackworm, however. These tiny worms twist together by the thousands to form tightly packed blobs reminiscent of a forkful of squirming spaghetti. While these tangles take minutes to form, intertwined blackworms can wriggle free in a matter of milliseconds. Now scientists have finally straightened out how these legless escape artists use only a simple collection of muscles and neurons to

Anyone who’s grappled with jumbled headphones knows the difficulty of disentangling snarled cords. A tight knot is nothing for a California blackworm, however. These tiny worms twist together by the thousands to form tightly packed blobs reminiscent of a forkful of squirming spaghetti. While these tangles take minutes to form, intertwined blackworms can wriggle free in a matter of milliseconds. Now scientists have finally straightened out how these legless escape artists use only a simple collection of muscles and neurons to  For the millions who were enraged, disgusted, and shocked by the Capitol riots of January 6, the enduring object of skepticism has been not so much the lie that provoked the riots but the believers themselves. A year out, and book publishers confirmed this, releasing titles that addressed the question still addling public consciousness: How can people believe this shit? A minority of rioters at the Capitol had nefarious intentions rooted in authentic ideology, but most of them conveyed no purpose other than to announce to the world that they believed — specifically, that the 2020 election was hijacked through an international conspiracy — and that nothing could sway their confidence. This belief possessed them, not the other way around.

For the millions who were enraged, disgusted, and shocked by the Capitol riots of January 6, the enduring object of skepticism has been not so much the lie that provoked the riots but the believers themselves. A year out, and book publishers confirmed this, releasing titles that addressed the question still addling public consciousness: How can people believe this shit? A minority of rioters at the Capitol had nefarious intentions rooted in authentic ideology, but most of them conveyed no purpose other than to announce to the world that they believed — specifically, that the 2020 election was hijacked through an international conspiracy — and that nothing could sway their confidence. This belief possessed them, not the other way around. Whenever I leave my Berlin apartment, the first thing I see is a sign saying CHICKEN HAUS BURGER; the second is a café blackboard announcing: « You can’t buy happiness but you can buy CROIFFLE and that’s kind of the same thing. » A billboard advertises an upcoming film as « ein STATEMENT für GIRLPOWER »; one shop promises a wide range of Funsocken. Rather more disturbing — particularly here in Neukölln, a neighbourhood copiously populated by leftie Americans and families from the Middle East — is the Arabic-German barber shop called WHITE BOSS. And when I go downtown to the bookstore where I occasionally host readings, the only good coffee nearby is served by a place unbelievably named PURE ORIGINS.

Whenever I leave my Berlin apartment, the first thing I see is a sign saying CHICKEN HAUS BURGER; the second is a café blackboard announcing: « You can’t buy happiness but you can buy CROIFFLE and that’s kind of the same thing. » A billboard advertises an upcoming film as « ein STATEMENT für GIRLPOWER »; one shop promises a wide range of Funsocken. Rather more disturbing — particularly here in Neukölln, a neighbourhood copiously populated by leftie Americans and families from the Middle East — is the Arabic-German barber shop called WHITE BOSS. And when I go downtown to the bookstore where I occasionally host readings, the only good coffee nearby is served by a place unbelievably named PURE ORIGINS. Suppose a large inbound asteroid were discovered, and we learned that half of all astronomers gave it at least 10% chance of causing human extinction, just as a similar asteroid exterminated the dinosaurs about 66 million years ago. Since we have such a long history of thinking about this threat and what to do about it, from scientific conferences to Hollywood blockbusters, you might expect humanity to shift into high gear with a deflection mission to steer it in a safer direction.

Suppose a large inbound asteroid were discovered, and we learned that half of all astronomers gave it at least 10% chance of causing human extinction, just as a similar asteroid exterminated the dinosaurs about 66 million years ago. Since we have such a long history of thinking about this threat and what to do about it, from scientific conferences to Hollywood blockbusters, you might expect humanity to shift into high gear with a deflection mission to steer it in a safer direction. Philosophers can be quirky. Take Ludwig Wittgenstein. His rooms in Cambridge were bare except for two deck chairs, a camp bed, and sets of identical clothes in a wardrobe. When asked what he wanted to eat, he said he didn’t care just so long as it was the same thing every day. He refused to lunch at high table in Trinity College, not wanting to set himself literally above other people. But then he had a special table made at the same height as that of the students so he could sit alone.

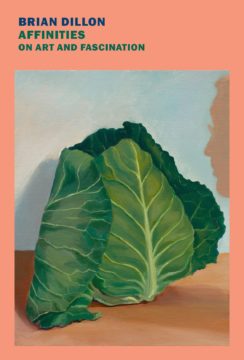

Philosophers can be quirky. Take Ludwig Wittgenstein. His rooms in Cambridge were bare except for two deck chairs, a camp bed, and sets of identical clothes in a wardrobe. When asked what he wanted to eat, he said he didn’t care just so long as it was the same thing every day. He refused to lunch at high table in Trinity College, not wanting to set himself literally above other people. But then he had a special table made at the same height as that of the students so he could sit alone. As Dillon explains at the outset of Affinities, he decided to write this collection after reflecting on his own writing career. Dillon, a professor of creative writing at Queen Mary University of London and an author of eight books, has spent more than 20 years writing about visual art for magazines, books, and exhibition catalogs. Over the course of his long tenure as an art critic and essayist, he found himself not only using the word “affinity” as an adjective when speaking or writing but also bringing forth the vague practice of it, particularly when trying to draw connections between artists’ work and their studio ephemera, personal notes, and historical anecdotes. “How to describe, as a writer, the relation it seemed the artists had with their chosen and not chosen,” Dillon asks in the book’s first essay, which continues intermittently throughout the collection, alternating with essays on the first noted photograph of a person, an illustration of a fly’s eyeball, professional street photos, and other artworks which have inexplicably clung to Dillon’s mind.

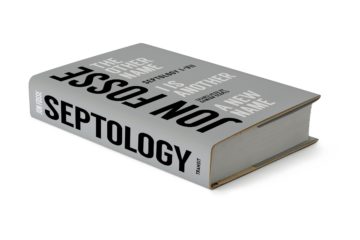

As Dillon explains at the outset of Affinities, he decided to write this collection after reflecting on his own writing career. Dillon, a professor of creative writing at Queen Mary University of London and an author of eight books, has spent more than 20 years writing about visual art for magazines, books, and exhibition catalogs. Over the course of his long tenure as an art critic and essayist, he found himself not only using the word “affinity” as an adjective when speaking or writing but also bringing forth the vague practice of it, particularly when trying to draw connections between artists’ work and their studio ephemera, personal notes, and historical anecdotes. “How to describe, as a writer, the relation it seemed the artists had with their chosen and not chosen,” Dillon asks in the book’s first essay, which continues intermittently throughout the collection, alternating with essays on the first noted photograph of a person, an illustration of a fly’s eyeball, professional street photos, and other artworks which have inexplicably clung to Dillon’s mind. Innumerable nothings happen in the dim, watery fjord lands of Jon Fosse’s novels and plays. In the novella Aliss at the Fire, a woman named Signe lies on a bench and remembers (or hallucinates) her husband Asle, who disappeared one night two decades earlier, after announcing he would head out onto the fjord. In Fosse’s magnum opus, Septology, a widowed painter, also named Asle, spends hundreds of pages thinking about his wife, his doppelgänger, his neighbor and the painting he can’t seem to rid himself of. Almost nothing occurs. And everything that does, recurs.

Innumerable nothings happen in the dim, watery fjord lands of Jon Fosse’s novels and plays. In the novella Aliss at the Fire, a woman named Signe lies on a bench and remembers (or hallucinates) her husband Asle, who disappeared one night two decades earlier, after announcing he would head out onto the fjord. In Fosse’s magnum opus, Septology, a widowed painter, also named Asle, spends hundreds of pages thinking about his wife, his doppelgänger, his neighbor and the painting he can’t seem to rid himself of. Almost nothing occurs. And everything that does, recurs.