David Marchese in The New York Times:

When OpenAI released its artificial-intelligence chatbot, ChatGPT, to the public at the end of last year, it unleashed a wave of excitement, fear, curiosity and debate that has only grown as rival competitors have accelerated their efforts and members of the public have tested out new A.I.-powered technology. Gary Marcus, an emeritus professor of psychology and neural science at New York University and an A.I. entrepreneur himself, has been one of the most prominent — and critical — voices in these discussions. More specifically, Marcus, a prolific author and writer of the Substack “The Road to A.I. We Can Trust,” as well as the host of a new podcast, “Humans vs. Machines,” has positioned himself as a gadfly to A.I. boosters. At a recent TED conference, he even called for the establishment of an international institution to help govern A.I.’s development and use. “I’m not one of these long-term riskers who think the entire planet is going to be taken over by robots,” says Marcus, who is 53. “But I am worried about what bad actors can do with these things, because there is no control over them. We’re not really grappling with what that means or what the scale could be.”

When OpenAI released its artificial-intelligence chatbot, ChatGPT, to the public at the end of last year, it unleashed a wave of excitement, fear, curiosity and debate that has only grown as rival competitors have accelerated their efforts and members of the public have tested out new A.I.-powered technology. Gary Marcus, an emeritus professor of psychology and neural science at New York University and an A.I. entrepreneur himself, has been one of the most prominent — and critical — voices in these discussions. More specifically, Marcus, a prolific author and writer of the Substack “The Road to A.I. We Can Trust,” as well as the host of a new podcast, “Humans vs. Machines,” has positioned himself as a gadfly to A.I. boosters. At a recent TED conference, he even called for the establishment of an international institution to help govern A.I.’s development and use. “I’m not one of these long-term riskers who think the entire planet is going to be taken over by robots,” says Marcus, who is 53. “But I am worried about what bad actors can do with these things, because there is no control over them. We’re not really grappling with what that means or what the scale could be.”

More here.

Human technologies are therefore not much different from other innovations produced in our planet’s 3.8-billion-year living history — with the exception that they are in our evolutionary future, not our past. Multicellular organisms evolved vision; what I will call “multisocietial aggregates” of humans evolved microscopes and telescopes, which are capable of seeing into the smallest and largest scales of our universe. Life seeing life. All of these innovations are based on trial and error and selection and evolution on past objects.

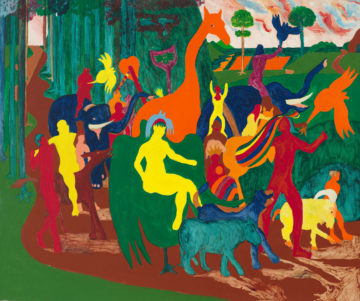

Human technologies are therefore not much different from other innovations produced in our planet’s 3.8-billion-year living history — with the exception that they are in our evolutionary future, not our past. Multicellular organisms evolved vision; what I will call “multisocietial aggregates” of humans evolved microscopes and telescopes, which are capable of seeing into the smallest and largest scales of our universe. Life seeing life. All of these innovations are based on trial and error and selection and evolution on past objects. There is no exact word for what Thompson does with the Old Masters. His paintings—the subject of “Bob Thompson: Agony & Ecstasy,” the unmissable show at Rosenfeld, and another, “Bob Thompson: So Let Us All Be Citizens,” at 52 Walker—contain hundreds of motifs snatched from the Western canon, wedged into dense compositions, and coated in bright colors. The results are too calm for parody and too self-secure for homage. Stanley Crouch thought that Thompson, a jazz fanatic, improvised on European art the way a saxophonist improvises on standards, but even that seems a notch too reverent. He doesn’t riff on masterpieces so much as rifle through them, grabbing a handful of Goya or Tintoretto as though reaching for the cadmium yellow. For “The Entombment” (1960), his painting of a hatted man tumbling off his horse, he seems to have taken the lifeless, drooping torso from El Greco’s “The Entombment of Christ” (which El Greco lifted from Michelangelo, but that’s another story) and cast it in a drama of his own making, so that every brushstroke whooshes toward the bottom like a waterfall.

There is no exact word for what Thompson does with the Old Masters. His paintings—the subject of “Bob Thompson: Agony & Ecstasy,” the unmissable show at Rosenfeld, and another, “Bob Thompson: So Let Us All Be Citizens,” at 52 Walker—contain hundreds of motifs snatched from the Western canon, wedged into dense compositions, and coated in bright colors. The results are too calm for parody and too self-secure for homage. Stanley Crouch thought that Thompson, a jazz fanatic, improvised on European art the way a saxophonist improvises on standards, but even that seems a notch too reverent. He doesn’t riff on masterpieces so much as rifle through them, grabbing a handful of Goya or Tintoretto as though reaching for the cadmium yellow. For “The Entombment” (1960), his painting of a hatted man tumbling off his horse, he seems to have taken the lifeless, drooping torso from El Greco’s “The Entombment of Christ” (which El Greco lifted from Michelangelo, but that’s another story) and cast it in a drama of his own making, so that every brushstroke whooshes toward the bottom like a waterfall. Terese Svoboda has been a powerhouse of literary production in recent years, publishing five books since 2018, and partaking of a formidable array of genres and approaches.

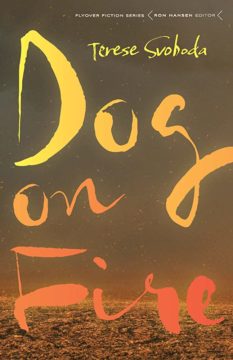

Terese Svoboda has been a powerhouse of literary production in recent years, publishing five books since 2018, and partaking of a formidable array of genres and approaches.  Machine learning models are incredibly powerful tools. They extract deeply hidden patterns in large data sets that our limited human brains can’t parse. These complex algorithms, then, need to be incomprehensible “black boxes,” because a model that we could crack open and understand would be useless. Right?

Machine learning models are incredibly powerful tools. They extract deeply hidden patterns in large data sets that our limited human brains can’t parse. These complex algorithms, then, need to be incomprehensible “black boxes,” because a model that we could crack open and understand would be useless. Right? Has anyone exerted as much influence over the spy genre as Ian Fleming? Examples of espionage fiction may have predated his transition from naval officer to novelist by well over a century, but it wasn’t until the appearance of the British Secret Service’s finest asset, James Bond, that it became a cultural phenomenon (a feeling strengthened by the character’s legendary reinvention as one of cinema’s greatest icons from 1962’s

Has anyone exerted as much influence over the spy genre as Ian Fleming? Examples of espionage fiction may have predated his transition from naval officer to novelist by well over a century, but it wasn’t until the appearance of the British Secret Service’s finest asset, James Bond, that it became a cultural phenomenon (a feeling strengthened by the character’s legendary reinvention as one of cinema’s greatest icons from 1962’s  A common complaint in America today is that politics and even society as a whole

A common complaint in America today is that politics and even society as a whole  Dazzling intricacies of brain structure are revealed every day, but one of the most obvious aspects of brain wiring eludes neuroscientists. The nervous system is cross-wired, so that the left side of the brain controls the right half of the body and vice versa. Every doctor relies upon this fact in performing neurological exams, but when I asked my doctor last week why this should be, all I got was a shrug. So I asked

Dazzling intricacies of brain structure are revealed every day, but one of the most obvious aspects of brain wiring eludes neuroscientists. The nervous system is cross-wired, so that the left side of the brain controls the right half of the body and vice versa. Every doctor relies upon this fact in performing neurological exams, but when I asked my doctor last week why this should be, all I got was a shrug. So I asked  Ramped up, amped up, ratchet up, gin up, up the ante, double down, jump-start, be behind the curve, swim against the tide, go south, go belly up, level the playing field, open the floodgates, think outside the box, push the edge of the envelope, pull out all the stops, take the foot off the pedal, pump the brakes, grease the wheel, circle the wagons, charge full steam ahead, pass with flying colors, move the goal posts, pour gasoline on, add fuel to the fire, fly under the radar, add insult to injury, grow by leaps and bounds, only time will tell, go to hell in a handbasket, put the genie back in the bottle, throw the baby out with the bathwater, rearrange the deck chairs on the Titanic, have your cake and eat it too, a taste of one’s own medicine, stick to one’s guns, above one’s pay grade, punch above one’s weight, lick one’s wounds, pack a punch, roll with the punches, come apart at the seams, throw a wrench into, caught in the cross hairs, cross the Rubicon, tempt fate, go ballistic, on tenterhooks, hit the nail on the head…

Ramped up, amped up, ratchet up, gin up, up the ante, double down, jump-start, be behind the curve, swim against the tide, go south, go belly up, level the playing field, open the floodgates, think outside the box, push the edge of the envelope, pull out all the stops, take the foot off the pedal, pump the brakes, grease the wheel, circle the wagons, charge full steam ahead, pass with flying colors, move the goal posts, pour gasoline on, add fuel to the fire, fly under the radar, add insult to injury, grow by leaps and bounds, only time will tell, go to hell in a handbasket, put the genie back in the bottle, throw the baby out with the bathwater, rearrange the deck chairs on the Titanic, have your cake and eat it too, a taste of one’s own medicine, stick to one’s guns, above one’s pay grade, punch above one’s weight, lick one’s wounds, pack a punch, roll with the punches, come apart at the seams, throw a wrench into, caught in the cross hairs, cross the Rubicon, tempt fate, go ballistic, on tenterhooks, hit the nail on the head… Greg Afinogenov in the LRB:

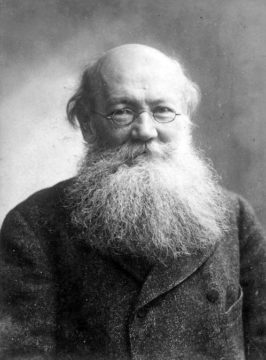

Greg Afinogenov in the LRB: Kieran Setiya in the LA Review of Books:

Kieran Setiya in the LA Review of Books: Jay Newman and Meyrick Chapman in Politico:

Jay Newman and Meyrick Chapman in Politico: Marco D’Eramo in Sidecar:

Marco D’Eramo in Sidecar: