Category: Recommended Reading

In Gaziantep

Naomi Cohen at n+1:

ISTANBUL HAS THE WORLD’S LARGEST AIRPORT, but our corner of it is as hushed as a hospital waiting room. There are no X-ray screeners, no rowed seating or gates, no last calls. Only an expensive-looking clock that makes our heads turn. Every tick seems to mark another passing, sorting the living from the dead.

ISTANBUL HAS THE WORLD’S LARGEST AIRPORT, but our corner of it is as hushed as a hospital waiting room. There are no X-ray screeners, no rowed seating or gates, no last calls. Only an expensive-looking clock that makes our heads turn. Every tick seems to mark another passing, sorting the living from the dead.

Some sixty rescue volunteers from across Istanbul, we have gathered here, the second morning after two earthquakes sheared a 185-mile gash from the lower gut of Turkey into the western tip of Syria. We will fly, a team leader says as they hand me a blank boarding pass, to the epicenter of the first quake (Maraş), from where we will drive to the epicenter of the second (Gaziantep), to join our co-volunteers in Islahiye, a town about halfway down the gash and deep into its scab. Our task is to help free people from their homes and to do it fast. Some of them are presently trying to free themselves.

more here.

Joel Coen Puts His Spins On Lee Friedlander

Arthur Lubow at the New York Times:

Coen began by leafing through books of Friedlander pictures and decided to arrange the new book to draw attention to Friedlander’s compositional approaches. “Looking through these books and going back and forth, it was a pattern recognition for me — patterns which I know are instinctive but are manifold in everything he does,” he said.

Coen began by leafing through books of Friedlander pictures and decided to arrange the new book to draw attention to Friedlander’s compositional approaches. “Looking through these books and going back and forth, it was a pattern recognition for me — patterns which I know are instinctive but are manifold in everything he does,” he said.

He began with the artist’s simplest formal structures and advanced into greater complexity. “The first thing I noticed was the splitting,” Coen explained. Friedlander repeatedly organizes a picture with a vertical post dividing the frame. “The post, the post,” Coen continued. “Then I see the posts are slightly diagonal, and the affinity between the diagonal post and how car interiors are designed. Then I see how he uses diagonal shadows like the posts. Now I see how he is using television screens like windows. Now I see how he is using light to define the same areas.” As the book unfolds, the themes and variations become evident.

more here.

Wednesday, May 3, 2023

Norman Mailer’s Ripe Garbage

Rob Madole in The Baffler:

NORMAN MAILER WAS CHARACTERISTICALLY AROUSED the first time he caught a whiff of death drifting from a nearby battlefield. “A curious smell,” he described in a February 1945 letter to his first wife Bea, whom he’d charged with preserving his correspondence as preliminary notes for the big war novel he’d conceived in basic training. “A smell of decay, not exactly sweet as the authors have it, but a good deal like feces leavened with ripe garbage.” Mailer’s tone is that of a gourmand encountering a rare vintage; his olfactory exemplar is Leo Tolstoy, who’d written evocatively in War and Peace about the “stench of rotting flesh” in military hospitals after the Battle of Friedland, the mere memory of which gives Nikolai Rostov, even weeks after the event, sensory hallucinations.

NORMAN MAILER WAS CHARACTERISTICALLY AROUSED the first time he caught a whiff of death drifting from a nearby battlefield. “A curious smell,” he described in a February 1945 letter to his first wife Bea, whom he’d charged with preserving his correspondence as preliminary notes for the big war novel he’d conceived in basic training. “A smell of decay, not exactly sweet as the authors have it, but a good deal like feces leavened with ripe garbage.” Mailer’s tone is that of a gourmand encountering a rare vintage; his olfactory exemplar is Leo Tolstoy, who’d written evocatively in War and Peace about the “stench of rotting flesh” in military hospitals after the Battle of Friedland, the mere memory of which gives Nikolai Rostov, even weeks after the event, sensory hallucinations.

Mailer, however, didn’t share Rostov’s battlefield revulsion, even after the Jeep giving him a tour swerved down a dirt road and arrived at a field of putrefying Japanese corpses, “perhaps twenty or thirty . . . swollen to the dimensions of very obese men.”

More here.

Comparing Physician and Artificial Intelligence Chatbot Responses to Patient Questions Posted to a Public Social Media Forum

John W. Ayers, Adam Poliak, Mark Dredze, et al, at the JAMA Network:

Question: Can an artificial intelligence chatbot assistant, provide responses to patient questions that are of comparable quality and empathy to those written by physicians?

Question: Can an artificial intelligence chatbot assistant, provide responses to patient questions that are of comparable quality and empathy to those written by physicians?

Findings: In this cross-sectional study of 195 randomly drawn patient questions from a social media forum, a team of licensed health care professionals compared physician’s and chatbot’s responses to patient’s questions asked publicly on a public social media forum. The chatbot responses were preferred over physician responses and rated significantly higher for both quality and empathy.

Meaning: These results suggest that artificial intelligence assistants may be able to aid in drafting responses to patient questions.

More here.

Mark Blyth Debunking Myths About The End of the US Dollar Dominance

On the Wild West of Internet Regulations and the Birth of Pornhub

Kelsy Burke in Literary Hub:

In the fictional world of the Broadway musical Avenue Q, Kate Monster is a puppet with a sweet demeanor, a lavender-colored turtleneck, and a bob hairstyle. She works as an assistant kindergarten teacher, and when she finally gets to teach a kindergarten lesson all by herself, she chooses to teach children about the wonders of the World Wide Web. But when she describes her lesson to a reclusive, shaggy-haired neighbor named Trekkie Monster, he interrupts every line with what he says is the real reason for the Internet: porn.

In the fictional world of the Broadway musical Avenue Q, Kate Monster is a puppet with a sweet demeanor, a lavender-colored turtleneck, and a bob hairstyle. She works as an assistant kindergarten teacher, and when she finally gets to teach a kindergarten lesson all by herself, she chooses to teach children about the wonders of the World Wide Web. But when she describes her lesson to a reclusive, shaggy-haired neighbor named Trekkie Monster, he interrupts every line with what he says is the real reason for the Internet: porn.

When Avenue Q premiered in 2003 with its song “The Internet is for Porn,” it became the first Broadway cast album to be released with a parental advisory label. At the time, a majority of American households, 62 million of them, owned a computer that connected to the internet. And when it came to its emergence, Trekkie Monster captured a widespread fear.

“All-pornography, all-the-time,” is how Pamela Paul, the author of the 2005 book Pornified, put it.

More here.

Travel, Pleasure, Madness: Waldemar On The Rococo

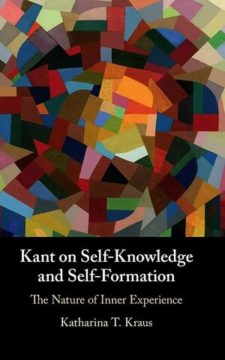

Kant on Self-Knowledge and Self-Formation

Pirachula Chulanon at Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews:

Kant’s account of the self is no doubt the most fascinating but also the most difficult facet of his philosophical thinking. It is complex, multi-layered, and inextricably bound with many central tenets of his system. It is no surprise, then, that interpreters rarely attempt to reconstruct the whole picture but more often focus on a single aspect of it. What is lacking in localized approaches, however, is the sense of how different pieces of the puzzle fit together. Katharina Kraus’s ambitious new book remedies this by offering a much-needed comprehensive treatment of Kant’s view on the self that straddles the a priori-empirical as well as the theoretical-practical divide. The book skillfully maps out crucial interpretive issues that frame different parts of Kant’s picture and the various stances one could take toward them, while introducing fresh alternatives to the discussion. Its thorough engagement with both Kant’s writings and existing scholarship is exemplary. This book deserves to become a standard reference point for any discussion of Kant’s view on the self.

Kant’s account of the self is no doubt the most fascinating but also the most difficult facet of his philosophical thinking. It is complex, multi-layered, and inextricably bound with many central tenets of his system. It is no surprise, then, that interpreters rarely attempt to reconstruct the whole picture but more often focus on a single aspect of it. What is lacking in localized approaches, however, is the sense of how different pieces of the puzzle fit together. Katharina Kraus’s ambitious new book remedies this by offering a much-needed comprehensive treatment of Kant’s view on the self that straddles the a priori-empirical as well as the theoretical-practical divide. The book skillfully maps out crucial interpretive issues that frame different parts of Kant’s picture and the various stances one could take toward them, while introducing fresh alternatives to the discussion. Its thorough engagement with both Kant’s writings and existing scholarship is exemplary. This book deserves to become a standard reference point for any discussion of Kant’s view on the self.

more here.

Annie Ernaux And The Superstore

Adrienne Raphel at The Paris Review:

The first and only time I went to the Walmart in Iowa City was surreal. When I was in high school, my parents’ business-oriented small press had published a book called The Case Against Walmart that called for a national consumer boycott of the company; the author denounced everything from the superstore’s destruction of environmentally protected lands to its sweatshop labor to its knockoff merchandise. So by the time I made a pilgrimage out to the superstore at age twenty-one, I hadn’t stepped in a Walmart for nearly a decade, and it had acquired this transgressive power—the very act of crossing the threshold was as shameful as it was thrilling. Immediately, I sensed the store’s anonymizing power: outside, I was nearby the Iowa Municipal Airport, en route to the Hy-Vee grocery store; inside, I was anywhere. I didn’t know what I expected, but it was wonderful, and terrible, and weird, and empty, but also full of stuff. In the real world, I was allergic to animals, but I found myself hypnotized in the pet aisle: snake food, dry cat food, wet cat food, Iams, I am what I am. Each shade of paint chip in the Benjamin Moore display bouquet was more erotic than the one before. Primrose Petals, I Love You Pink, Pretty Pink, Hot Lips. Everything was too bright, oversaturated, illuminated in fluorescent Super Soaker–level high beams. I wasn’t high; I didn’t need to be. I barely saw another human, but the accumulation of things constituted many lifetimes of living. I was in a mass graveyard—a place defined by, as Annie Ernaux puts it, “the dead silence of goods as far as the eye could see.”

The first and only time I went to the Walmart in Iowa City was surreal. When I was in high school, my parents’ business-oriented small press had published a book called The Case Against Walmart that called for a national consumer boycott of the company; the author denounced everything from the superstore’s destruction of environmentally protected lands to its sweatshop labor to its knockoff merchandise. So by the time I made a pilgrimage out to the superstore at age twenty-one, I hadn’t stepped in a Walmart for nearly a decade, and it had acquired this transgressive power—the very act of crossing the threshold was as shameful as it was thrilling. Immediately, I sensed the store’s anonymizing power: outside, I was nearby the Iowa Municipal Airport, en route to the Hy-Vee grocery store; inside, I was anywhere. I didn’t know what I expected, but it was wonderful, and terrible, and weird, and empty, but also full of stuff. In the real world, I was allergic to animals, but I found myself hypnotized in the pet aisle: snake food, dry cat food, wet cat food, Iams, I am what I am. Each shade of paint chip in the Benjamin Moore display bouquet was more erotic than the one before. Primrose Petals, I Love You Pink, Pretty Pink, Hot Lips. Everything was too bright, oversaturated, illuminated in fluorescent Super Soaker–level high beams. I wasn’t high; I didn’t need to be. I barely saw another human, but the accumulation of things constituted many lifetimes of living. I was in a mass graveyard—a place defined by, as Annie Ernaux puts it, “the dead silence of goods as far as the eye could see.”

more here.

Top 10 books about being poor in America

Monica Potts in The Guardian:

For all its wealth and devotion to the myth of the American Dream, the US allows many more of its citizens to live in poverty than other wealthy countries do. We hold the 10th highest poverty rate in a 2021 ranking of OECD countries, with almost 38 million Americans living in poverty. Even that number is calculated using an outdated measure that probably doesn’t fully account for the number of families that are truly struggling. How is it that a country that prides itself on success and progress can allow so many of its citizens to go without? It’s an urgent question we’ve been writing about – failing to solve – for a long time.

For all its wealth and devotion to the myth of the American Dream, the US allows many more of its citizens to live in poverty than other wealthy countries do. We hold the 10th highest poverty rate in a 2021 ranking of OECD countries, with almost 38 million Americans living in poverty. Even that number is calculated using an outdated measure that probably doesn’t fully account for the number of families that are truly struggling. How is it that a country that prides itself on success and progress can allow so many of its citizens to go without? It’s an urgent question we’ve been writing about – failing to solve – for a long time.

The books about poverty that resonate most for me come in two forms. Novels and narrative nonfiction books often take a personal, sometimes painfully vivid and honest portrayal of a family or individual in a way that can personalise the potentially abstract issue for readers. My own book, The Forgotten Girls, follows in this tradition. To write it, I returned home to my small, poor town in the Arkansas Ozarks after many years of living in big cities on the east coast to find my childhood best friend: through our reconnection, I explored the ways that the different places we lived marked our adult lives.

More here.

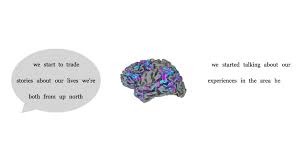

A.I. Is Getting Better at Mind-Reading

Oliver Whang in The New York Times:

The study centered on three participants, who came to Dr. Huth’s lab for 16 hours over several days to listen to “The Moth” and other narrative podcasts. As they listened, an fMRI scanner recorded the blood oxygenation levels in parts of their brains. The researchers then used a large language model to match patterns in the brain activity to the words and phrases that the participants had heard.

The study centered on three participants, who came to Dr. Huth’s lab for 16 hours over several days to listen to “The Moth” and other narrative podcasts. As they listened, an fMRI scanner recorded the blood oxygenation levels in parts of their brains. The researchers then used a large language model to match patterns in the brain activity to the words and phrases that the participants had heard.

Large language models like OpenAI’s GPT-4 and Google’s Bard are trained on vast amounts of writing to predict the next word in a sentence or phrase. In the process, the models create maps indicating how words relate to one another. A few years ago, Dr. Huth noticed that particular pieces of these maps — so-called context embeddings, which capture the semantic features, or meanings, of phrases — could be used to predict how the brain lights up in response to language. In a basic sense, said Shinji Nishimoto, a neuroscientist at Osaka University who was not involved in the research, “brain activity is a kind of encrypted signal, and language models provide ways to decipher it.”

In their study, Dr. Huth and his colleagues effectively reversed the process, using another A.I. to translate the participant’s fMRI images into words and phrases. The researchers tested the decoder by having the participants listen to new recordings, then seeing how closely the translation matched the actual transcript.

More here.

Wednesday Poem

At Noon

At a mountain inn, high above the bulky green of chestnuts,

The three of us were sitting next to an Italian family

Under the tiered levels of pine forests.

Nearby a little girl pumped water from a well.

The air was huge with the voice of swallows.

Ooo, I heard a singing in me, ooo.

What a noon, no other like it will recur,

Now when I’m sitting next to her and her

While the stages of past life come together

And a jug of wine stands on a checkered tablecloth.

The granite rocks of that island were washed by the sea.

The three of us were one self-delighting thought

And the resinous scent of Corsican summer was with us.

by Czeslaw Milosz

from Unattainable Earth

Ecco Press, 1964

Tuesday, May 2, 2023

Kieran Setiya reviews “What’s the Use of Philosophy?” by Philip Kitcher

Kieran Setiya in the London Review of Books:

In August 1977, the New York Times ran a profile of the philosopher Saul Kripke, then 36 years old. Aged 17, he had proved a new result in modal logic – the logic of necessity and possibility – by building a mathematical model of ‘possible worlds’. He went on to transform philosophy, reviving dormant metaphysical questions. What makes us the particular people we are? Does science tell us how the world must be, not just how it is? At thirty, Kripke gave the lectures that made his name – they were published as Naming and Necessity in 1972 – and he went on to write a groundbreaking book about Wittgenstein’s later philosophy. Yet despite these achievements, the New York Times noted, he was little known outside his field. ‘Philosophy has become such an arcane discipline that it leaves most laymen gasping for meaning.’ It was also divided between two very different visions: ‘The technicians dream of one master key that could make a science of all philosophy, while the romantics dream of a “big move” that would make philosophy grab the world again and prove that philosophical intuition has not run dry.’

In August 1977, the New York Times ran a profile of the philosopher Saul Kripke, then 36 years old. Aged 17, he had proved a new result in modal logic – the logic of necessity and possibility – by building a mathematical model of ‘possible worlds’. He went on to transform philosophy, reviving dormant metaphysical questions. What makes us the particular people we are? Does science tell us how the world must be, not just how it is? At thirty, Kripke gave the lectures that made his name – they were published as Naming and Necessity in 1972 – and he went on to write a groundbreaking book about Wittgenstein’s later philosophy. Yet despite these achievements, the New York Times noted, he was little known outside his field. ‘Philosophy has become such an arcane discipline that it leaves most laymen gasping for meaning.’ It was also divided between two very different visions: ‘The technicians dream of one master key that could make a science of all philosophy, while the romantics dream of a “big move” that would make philosophy grab the world again and prove that philosophical intuition has not run dry.’

Philip Kitcher is with the romantics. He began his career working in relatively technical areas of the philosophy of mathematics and science, but soon turned towards contentious issues in biology – including creationism and evolutionary psychology – as well as the social nature of scientific practice.

More here.

‘The Godfather of A.I.’ Leaves Google and Warns of Danger Ahead

Cade Metz in the New York Times:

Geoffrey Hinton was an artificial intelligence pioneer. In 2012, Dr. Hinton and two of his graduate students at the University of Toronto created technology that became the intellectual foundation for the A.I. systems that the tech industry’s biggest companies believe is a key to their future.

Geoffrey Hinton was an artificial intelligence pioneer. In 2012, Dr. Hinton and two of his graduate students at the University of Toronto created technology that became the intellectual foundation for the A.I. systems that the tech industry’s biggest companies believe is a key to their future.

On Monday, however, he officially joined a growing chorus of critics who say those companies are racing toward danger with their aggressive campaign to create products based on generative artificial intelligence, the technology that powers popular chatbots like ChatGPT.

Dr. Hinton said he has quit his job at Google, where he has worked for more than a decade and became one of the most respected voices in the field, so he can freely speak out about the risks of A.I. A part of him, he said, now regrets his life’s work.

More here.

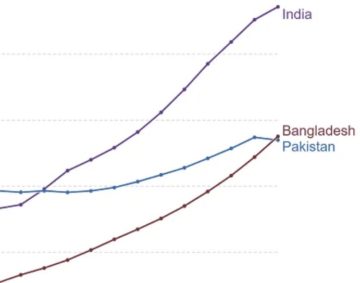

How Pakistan can join the South Asia growth boom

Murtaza Hussain at Noahpinion:

This past week was a happy one for many Indians, who celebrated the milestone of becoming the world’s most populous country at a time when their economic and political fortunes are also on the rise. For their neighbors in Pakistan the news of late has been far less upbeat. The past year has been a disastrous one for Pakistanis, who have faced spiraling inflation, low economic growth, catastrophic floods, terrorist attacks, and blowback from a political standoff that has paralyzed the country’s elite. While a rising economic tide has lifted many boats in Asia this century, Pakistan remains stuck in a cycle of stagnation and crisis.

This past week was a happy one for many Indians, who celebrated the milestone of becoming the world’s most populous country at a time when their economic and political fortunes are also on the rise. For their neighbors in Pakistan the news of late has been far less upbeat. The past year has been a disastrous one for Pakistanis, who have faced spiraling inflation, low economic growth, catastrophic floods, terrorist attacks, and blowback from a political standoff that has paralyzed the country’s elite. While a rising economic tide has lifted many boats in Asia this century, Pakistan remains stuck in a cycle of stagnation and crisis.

It is seldom appreciated in the West, but Pakistan is the fifth largest country in the world by population and its roughly 240 million citizens make it a larger country than Nigeria and Brazil.

More here.

Spectacular colorized film of the beginning of the German occupation of The Netherlands during WW-II

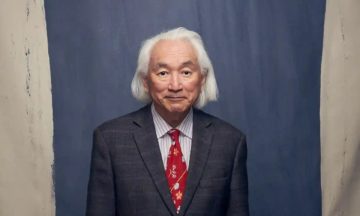

Quantum computers will transform our world, curing cancer and fixing the climate crisis

David Shariatmadari in The Guardian:

Have you been feeling anxious about technology lately? If so, you’re in good company. The United Nations has urged all governments to implement a set of rules designed to rein in artificial intelligence. An open letter, signed by such luminaries as Yuval Noah Harari and Elon Musk, called for research into the most advanced AI to be paused and measures taken to ensure it remains “safe … trustworthy, and loyal”. These pangs followed the launch last year of ChatGPT, a chatbot that can write you an essay on Milton as easily as it can generate a recipe for everything you happen to have in your cupboard that evening.

Have you been feeling anxious about technology lately? If so, you’re in good company. The United Nations has urged all governments to implement a set of rules designed to rein in artificial intelligence. An open letter, signed by such luminaries as Yuval Noah Harari and Elon Musk, called for research into the most advanced AI to be paused and measures taken to ensure it remains “safe … trustworthy, and loyal”. These pangs followed the launch last year of ChatGPT, a chatbot that can write you an essay on Milton as easily as it can generate a recipe for everything you happen to have in your cupboard that evening.

But what if the computers used to develop AI were replaced by ones able to make calculations not millions, but trillions of times faster? What if tasks that might take thousands of years to perform on today’s devices could be completed in a matter of seconds? Well, that’s precisely the future that physicist Michio Kaku is predicting. He believes we are about to leave the digital age behind for a quantum era that will bring unimaginable scientific and societal change. Computers will no longer use transistors, but subatomic particles, to make calculations, unleashing incredible processing power. Another physicist has likened it to putting “a rocket engine in your car”. How are you feeling now?

More here.

How Do We Ensure an A.I. Future That Allows for Human Thriving?

David Marchese in The New York Times:

When OpenAI released its artificial-intelligence chatbot, ChatGPT, to the public at the end of last year, it unleashed a wave of excitement, fear, curiosity and debate that has only grown as rival competitors have accelerated their efforts and members of the public have tested out new A.I.-powered technology. Gary Marcus, an emeritus professor of psychology and neural science at New York University and an A.I. entrepreneur himself, has been one of the most prominent — and critical — voices in these discussions. More specifically, Marcus, a prolific author and writer of the Substack “The Road to A.I. We Can Trust,” as well as the host of a new podcast, “Humans vs. Machines,” has positioned himself as a gadfly to A.I. boosters. At a recent TED conference, he even called for the establishment of an international institution to help govern A.I.’s development and use. “I’m not one of these long-term riskers who think the entire planet is going to be taken over by robots,” says Marcus, who is 53. “But I am worried about what bad actors can do with these things, because there is no control over them. We’re not really grappling with what that means or what the scale could be.”

When OpenAI released its artificial-intelligence chatbot, ChatGPT, to the public at the end of last year, it unleashed a wave of excitement, fear, curiosity and debate that has only grown as rival competitors have accelerated their efforts and members of the public have tested out new A.I.-powered technology. Gary Marcus, an emeritus professor of psychology and neural science at New York University and an A.I. entrepreneur himself, has been one of the most prominent — and critical — voices in these discussions. More specifically, Marcus, a prolific author and writer of the Substack “The Road to A.I. We Can Trust,” as well as the host of a new podcast, “Humans vs. Machines,” has positioned himself as a gadfly to A.I. boosters. At a recent TED conference, he even called for the establishment of an international institution to help govern A.I.’s development and use. “I’m not one of these long-term riskers who think the entire planet is going to be taken over by robots,” says Marcus, who is 53. “But I am worried about what bad actors can do with these things, because there is no control over them. We’re not really grappling with what that means or what the scale could be.”

More here.

Technology Is Not Artificially Replacing Life — It Is Life

Sara Walker at Noema:

Human technologies are therefore not much different from other innovations produced in our planet’s 3.8-billion-year living history — with the exception that they are in our evolutionary future, not our past. Multicellular organisms evolved vision; what I will call “multisocietial aggregates” of humans evolved microscopes and telescopes, which are capable of seeing into the smallest and largest scales of our universe. Life seeing life. All of these innovations are based on trial and error and selection and evolution on past objects.

Human technologies are therefore not much different from other innovations produced in our planet’s 3.8-billion-year living history — with the exception that they are in our evolutionary future, not our past. Multicellular organisms evolved vision; what I will call “multisocietial aggregates” of humans evolved microscopes and telescopes, which are capable of seeing into the smallest and largest scales of our universe. Life seeing life. All of these innovations are based on trial and error and selection and evolution on past objects.

Intelligence is playing a larger role in modern technology, but that is to be expected — intelligence itself improves via evolution. It generates more complex systems — cells, multicellular aggregates like humans, societies, artificial intelligence and now multisocietial aggregates like international companies and groups that interact at the planetary scale. So-called “artificial intelligences” — large language models, computer vision, automated devices, robotics and more — are often discussed as disembodied and disengaged from any evolutionary context.

more here.