Category: Recommended Reading

What became of politics in the Long 2010s

Mark Dunbar in The Hedgehog Review:

This was during the Long 2010s (2009-2022), a decade during which there occurred more mass protests than any decade in history. The protests were against the usual suspects: capitalism, racism, imperialism, greed, corruption. Two new books, Vincent Bevins’s If We Burn: The Mass Protest Decade and the Missing Revolution and The Populist Moment: The Left After the Great Recession by Arthur Borriello and Anton Jäger, are about these protests and why they seemed to summon more of what they protested against—more greed, more racism, more corruption. They take different approaches. The Populist Moment is an academic investigation into the electoral failures of left-wing candidates in Europe and the United States (Bernie Sanders, Jeremy Corbyn, Jean-Luc Melenchon, Greece’s Syriza party), while If We Burn is a journalistic account of street protests in the Third World (Brazil, Indonesia, Chile) as well as Turkey and Ukraine.

This was during the Long 2010s (2009-2022), a decade during which there occurred more mass protests than any decade in history. The protests were against the usual suspects: capitalism, racism, imperialism, greed, corruption. Two new books, Vincent Bevins’s If We Burn: The Mass Protest Decade and the Missing Revolution and The Populist Moment: The Left After the Great Recession by Arthur Borriello and Anton Jäger, are about these protests and why they seemed to summon more of what they protested against—more greed, more racism, more corruption. They take different approaches. The Populist Moment is an academic investigation into the electoral failures of left-wing candidates in Europe and the United States (Bernie Sanders, Jeremy Corbyn, Jean-Luc Melenchon, Greece’s Syriza party), while If We Burn is a journalistic account of street protests in the Third World (Brazil, Indonesia, Chile) as well as Turkey and Ukraine.

While the electoral and protest approaches are different, they yielded the same result. The protests and protest candidates failed because they lacked organizational structures and concrete policies. Protestors couldn’t make demands because they shunned the formal structures of decision-making that could have led to change; protest candidates couldn’t advance concrete policies because they had no confidence those policies would be electorally sustainable. In other words, where there was a will there was no way, and where there was a way there was no will.

More here.

Peter Sloterdijk & Slavoj Žižek

The Unending Quest To Build A Better Chicken

Boyce Upholt at Noema Magazine:

From a certain point of view, the extraordinary abundance of chickens might be seen as a positive development: Here is a source of protein that is cheaply produced, transportable, happily consumed by a huge number of people across the world. And thanks in part to Peterson’s efforts at improving feed conversion efficiency, chicken has a much slimmer carbon impact than beef, which contributes more than 9% of global emissions.

From a certain point of view, the extraordinary abundance of chickens might be seen as a positive development: Here is a source of protein that is cheaply produced, transportable, happily consumed by a huge number of people across the world. And thanks in part to Peterson’s efforts at improving feed conversion efficiency, chicken has a much slimmer carbon impact than beef, which contributes more than 9% of global emissions.

But the rise of poultry, and of poultry science, has not been great for the chickens themselves. They are now less functional animals than meat-growing machines. So much of a chicken’s energy gets devoted to growing as big as possible as fast as possible that the parts less useful to us humans — lungs and hearts, say — are neglected and wither. Due to underdeveloped immune systems, the birds are dosed with antibiotics. Many full-grown broilers are unable to stand under their weight. Activists and critics have called them “prisoners in their own bodies.”

more here.

Dancing And Time

Isabel Jacobs at Aeon Magazine:

Shortly after Rachel Bespaloff’s suicide in 1949, her friend Jean Wahl published fragments from her final unfinished project. ‘The Instant and Freedom’ condensed themes that occupied the Ukrainian-French philosopher throughout her life: music, rhythm, corporeality, movement and time. One of Bespaloff’s key ideas, ‘the instant’, is less a fragment of duration than a life-changing event, a moment of embodied metamorphosis. In the midst of a noisy world, torn between transience and eternity, the human being listens to the sound of history. Had she completed and published it, ‘The Instant and Freedom’ might have become the masterpiece of an important early existentialist thinker. Instead, her name is hardly mentioned today.

Shortly after Rachel Bespaloff’s suicide in 1949, her friend Jean Wahl published fragments from her final unfinished project. ‘The Instant and Freedom’ condensed themes that occupied the Ukrainian-French philosopher throughout her life: music, rhythm, corporeality, movement and time. One of Bespaloff’s key ideas, ‘the instant’, is less a fragment of duration than a life-changing event, a moment of embodied metamorphosis. In the midst of a noisy world, torn between transience and eternity, the human being listens to the sound of history. Had she completed and published it, ‘The Instant and Freedom’ might have become the masterpiece of an important early existentialist thinker. Instead, her name is hardly mentioned today.

Yet Bespaloff was a brilliant and original thinker, among the first wave of existentialists in France. Albert Camus, Jean-Paul Sartre and Gabriel Marcel all admired her.

more here.

Good Grief Gives Grief a Home For the Holidays

Laura Zornosa in Time:

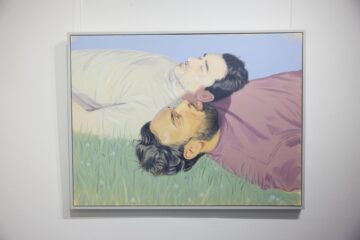

Art is the linchpin of Good Grief, a warm dramedy set in the heart of winter, out in theaters on Dec. 29 before coming to Netflix on Jan. 5. It’s a film that feels like snowfall: a gradual accumulation of a blanket of muted comfort. Dan Levy, who wrote, directed, and stars in the film, plays Marc, who is guided through grief by his best friends, Sophie (Ruth Negga) and Thomas (Himesh Patel) in the wake of his husband Oliver’s (Luke Evans) death. An artist who used to paint, Marc finds his way back to the canvas as he heals. The Marc we meet at the beginning of Good Grief is diminished—he stopped painting after his mom’s death, finding it too painful. Before Oliver died, Marc still made art, illustrating his husband’s books. But he shrank himself to magnify his husband. Now, he’s lost his partner. The people around him encourage him to pick up the paintbrush again.

Art is the linchpin of Good Grief, a warm dramedy set in the heart of winter, out in theaters on Dec. 29 before coming to Netflix on Jan. 5. It’s a film that feels like snowfall: a gradual accumulation of a blanket of muted comfort. Dan Levy, who wrote, directed, and stars in the film, plays Marc, who is guided through grief by his best friends, Sophie (Ruth Negga) and Thomas (Himesh Patel) in the wake of his husband Oliver’s (Luke Evans) death. An artist who used to paint, Marc finds his way back to the canvas as he heals. The Marc we meet at the beginning of Good Grief is diminished—he stopped painting after his mom’s death, finding it too painful. Before Oliver died, Marc still made art, illustrating his husband’s books. But he shrank himself to magnify his husband. Now, he’s lost his partner. The people around him encourage him to pick up the paintbrush again.

We learn over the course of the film that Marc and Oliver’s marriage was far from perfect; Marc holds his complex emotions about Oliver’s death at arm’s length, watching them circle the drain, but never quite emptying the bath water. First Thomas, and then a lover, Theo (Arnaud Valois), nudge him toward art to help him heal. “If you have the ability to write or to paint, sometimes that’s all you can do,” Levy says in an interview. “It might not look like the sobbing, fall-down-the-wall, on-the-floor hysteria that we’ve come to equate with grief or with loss. And that’s OK.”

More here.

This Mind-Reading Cap Can Translate Thoughts to Text Thanks to AI

Jason Dorrier in Singularity Hub:

Wearing an electrode-studded cap bristling with wires, a young man silently reads a sentence in his head. Moments later, a Siri-like voice breaks in, attempting to translate his thoughts into text, “Yes, I’d like a bowl of chicken soup, please.” It’s the latest example of computers translating a person’s thoughts into words and sentences.

Wearing an electrode-studded cap bristling with wires, a young man silently reads a sentence in his head. Moments later, a Siri-like voice breaks in, attempting to translate his thoughts into text, “Yes, I’d like a bowl of chicken soup, please.” It’s the latest example of computers translating a person’s thoughts into words and sentences.

Previously, researchers have used implants surgically placed in the brain or bulky, expensive machines to translate brain activity into text. The new approach, presented at this week’s NeurIPS conference by researchers from the University of Technology Sydney, is impressive for its use of a non-invasive EEG cap and the potential to generalize beyond one or two people. The team built an AI model called DeWave that’s trained on brain activity and language and linked it up to a large language model—the technology behind ChatGPT—to help convert brain activity into words. In a preprint posted on arXiv, the model beat previous top marks for EEG thought-to-text translation with an accuracy of roughly 40 percent. Chin-Teng Lin, corresponding author on the paper, told MSN they’ve more recently upped the accuracy to 60 percent. The results are still being peer-reviewed.

More here.

Friday Poem

Meanwhile

It waits. While I am walking through the pine trees

along the river, it is waiting. It has waited a long time.

In southern France, in Belgium, and even Alabama.

Now it waits in New England while I say grace over

almost everything: for a possum dead on someone’s lawn,

the sing light on a levee while Northampton sleeps,

and because the lanes between houses in Greek hamlets

are exactly the width of a donkey loaded on each side

with barley. Loneliness is the mother’s milk of America.

The heart is a foreign country whose language none

of us is good at. Winter lingers on in the woods,

but already it looks discarded as the birds return

and sing carelessly; as though there never was the power

or size of December. For nine years in me it has waited.

My life is pleasant, as usual. My body is a blessing

and my spirit clear. But the waiting does not let up.

by Jack Gilbert

Thursday, December 28, 2023

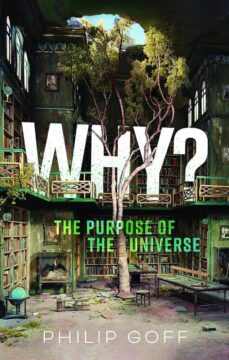

Galen Strawson reviews “Why? The Purpose of the Universe” by Philip Goff

Galen Strawson in The Guardian:

Why is there something rather than nothing? It’s meant to be the great unanswerable question. It’s certainly a poser. It would have been simpler if there’d been nothing: there wouldn’t be anything to explain.

Why is there something rather than nothing? It’s meant to be the great unanswerable question. It’s certainly a poser. It would have been simpler if there’d been nothing: there wouldn’t be anything to explain.

Some people think that if we knew more, we’d see that there couldn’t have been nothing. That wouldn’t surprise me. Others go further: they think we’d see that there couldn’t have been anything other than just what there is: this very universe, containing just the kind of stuff and laws of nature it does contain. That wouldn’t surprise me either, nor – I suspect – Einstein: “What really interests me,” he said, “is whether God had any choice in the creation of the world.” (Einstein’s God is a metaphorical device: “The word God is for me nothing more than the expression and product of human weaknesses.”)

Most people who ponder these things take a different view. They think the universe could in fact have been different. They think it’s puzzling that it turned out the way it did, with creatures like us in it. They are tempted by the idea that the universe has some point, some goal or meaning. In Why?, Philip Goff, professor of philosophy at Durham, argues for “cosmic purpose, the idea that the universe is directed towards certain goals, such as the emergence of life” and the existence of value.

I’m not convinced, but I’m impressed. Why? is direct, clear, open, acute, honest, companionable. It manages to stay down to earth even in its most abstract passages. I’m tempted to say, by way of praise, that it’s Liverpudlian, like its author.

More here.

In an evolutionary eyeblink, our species has gone from hunting and gathering to living in complex societies, and we need to rethink the story of this monumental transition

Michael Marshall in New Scientist:

For almost all of human existence, our species has been roaming the planet, living in small groups, hunting and gathering, moving to new areas when the climate was favourable, retreating when it turned nasty. For hundreds of thousands of years, our ancestors used fire to cook and warm themselves. They made tools, shelters, clothing and jewellery – although their possessions were limited to what they could carry. They occasionally came across other hominins, like Neanderthals, and sometimes had sex with them. Across vast swathes of time, history played out, unrecorded.

For almost all of human existence, our species has been roaming the planet, living in small groups, hunting and gathering, moving to new areas when the climate was favourable, retreating when it turned nasty. For hundreds of thousands of years, our ancestors used fire to cook and warm themselves. They made tools, shelters, clothing and jewellery – although their possessions were limited to what they could carry. They occasionally came across other hominins, like Neanderthals, and sometimes had sex with them. Across vast swathes of time, history played out, unrecorded.

Then, about 10,000 years ago, everything began to change.

In a few places, people started growing crops. They spent more time in the same spot. They built villages and towns. Various unsung geniuses invented writing, money, the wheel and gunpowder. Within just a few thousand years – the blink of an eye in evolutionary time – cities, empires and factories mushroomed all over the world. Today, Earth is surrounded by orbiting satellites and criss-crossed by internet cables. Nothing else like this has ever happened.

Archaeologists and anthropologists have sought to explain why this rapid and extraordinary transformation occurred.

More here.

Wounded Healers

Algis Valiunas in The New Atlantis:

Doctor Kay Redfield Jamison, a clinical psychologist, chaired professor of psychiatry at Johns Hopkins University, honorary professor of English at the University of St. Andrews, author of now seven books for the general reader on psychiatric subjects, co-author of the standard textbook on manic depression, and MacArthur award recipient, is the most important writer we have on severe mental illness. For the past thirty years she has charted the vagaries of sick minds and agonized souls, with her focus on manic-depressive illness — still her preferred name for what is now called “bipolar disorder.” Though the older term has fallen out of fashion, she finds it both more precise and more evocative than the one currently favored, which could apply to a car battery on the fritz or a geopolitical kerfuffle between rival superpowers. The more anodyne term for this frightful disease is believed to spare sufferers and their families the stigma of the depressed maniac. Sometimes, however, it is useful to give the frightful its full measure of respect by acknowledging openly how terrifying it can be.

More here.

Robert Sapolsky on the Science of Pleasure

The Philosopher of the Real World: Susanna Siegel moves beyond dialectical debates

Lydialyle Gibson in Harvard Magazine:

A specialist in epistemology and the philosophy of mind, Siegel has always been fascinated by perception: what and how we see, and the effect that has on what we can know. Her 2010 book, The Contents of Visual Experience, argued that conscious visual perception includes all kinds of complex properties: not just color, shape, light, and motion, but other, richer attributes, too. For instance, it encompasses what kind of thing we see—a tree, a bicycle, a dog?—and causal characteristics, like the property a knife can have while slicing through a piece of bread. Perception can even involve personal identity, Siegel argued: the property of being John Malkovich. The book’s central claim was that being able to visually recognize things, such as one’s own neighborhood, or pine trees, or John Malkovich, can influence how those things look to the person who sees them.

A specialist in epistemology and the philosophy of mind, Siegel has always been fascinated by perception: what and how we see, and the effect that has on what we can know. Her 2010 book, The Contents of Visual Experience, argued that conscious visual perception includes all kinds of complex properties: not just color, shape, light, and motion, but other, richer attributes, too. For instance, it encompasses what kind of thing we see—a tree, a bicycle, a dog?—and causal characteristics, like the property a knife can have while slicing through a piece of bread. Perception can even involve personal identity, Siegel argued: the property of being John Malkovich. The book’s central claim was that being able to visually recognize things, such as one’s own neighborhood, or pine trees, or John Malkovich, can influence how those things look to the person who sees them.

But as she was finishing that book, another question began to bother her: if being able to recognize your neighborhood influences how it looks to you, then couldn’t beliefs, desires, and fears do the same? And if prior beliefs could influence someone’s visual experience, how might those experiences, in turn, strengthen those very beliefs?

More here.

The quantum phantom

Zack Savitsky in Science:

Reclusive and disaffected, Ettore Majorana liked to work in the shadows. But after his friend Emilio Segrè dragged him into Enrico Fermi’s elite Roman physics club in the late 1920s, Majorana’s stature in atomic physics quickly grew. His mostly unpublished premonitions were eerily prescient: Among others, he famously intuited the existence of the neutron from prior experiments. And in 1937, he conjured up a completely new kind of particle. Physicists had learned that every fundamental particle seems to have an antimatter counterpart, an idea Segrè would later earn a Nobel Prize for verifying. Majorana realized the equation that leads to this duality could also describe a single particle with identical matter and antimatter personas, making it prone to annihilate itself.

Reclusive and disaffected, Ettore Majorana liked to work in the shadows. But after his friend Emilio Segrè dragged him into Enrico Fermi’s elite Roman physics club in the late 1920s, Majorana’s stature in atomic physics quickly grew. His mostly unpublished premonitions were eerily prescient: Among others, he famously intuited the existence of the neutron from prior experiments. And in 1937, he conjured up a completely new kind of particle. Physicists had learned that every fundamental particle seems to have an antimatter counterpart, an idea Segrè would later earn a Nobel Prize for verifying. Majorana realized the equation that leads to this duality could also describe a single particle with identical matter and antimatter personas, making it prone to annihilate itself.

Months later, the 31-year-old withdrew a large sum from his bank account, took a boat across the Tyrrhenian Sea, and vanished. To this day, nobody’s sure what happened to him, and the jury is also still out on whether his proposed particle exists. For example, some physicists still believe the neutrino—a wispy particle that pervades the universe—might be its own antiparticle, which could also help explain why the universe is filled with more matter than antimatter. But tests have so far proved inconclusive. However, scientists think they are close to approximating a Majorana particle in a much different guise. By confining electrons on flat surfaces, researchers can coax them into peculiar dances that collectively masquerade as a Majorana particle, much as the undulations of a flock of birds might appear like a swimming fish.

More here.

Thursday Poem

Sunstone—excerpt

Mary, Persephone, Héloise, show me

your face that I may see at last

my true face, that of another,

my face forever the face of us all,

face of the tree and the baker of bread,

face of the driver and the cloud and the sailor,

face of the sun and face of the stream,

face of Peter and Paul, face

of this crowd of hermits, wake me up,

I’ve already been born:

………………………………. life and death

make a pact within you, lady of night,

tower of clarity, queen of dawn,

lunar virgin, mother of mother sea,

body of the world, house of death,

I’ve been falling endlessly since my birth,

I fall in myself without touching bottom,

gather me in your eyes, collect

my scattered dust and reconcile my ashes,

bind these unjointed bones, blow over

my being, bury me deep in your earth,

and let your silence bring peace to thought

that rages against itself:

………………………………… open . . .

by Octavio Paz

from The Collected Poems

Carcanet Press Limited, 1998

Wednesday, December 27, 2023

J. M. Coetzee’s Conflicted Romanticism

Leo Robson at Bookforum:

HOW ROMANTIC IS J. M. COETZEE? At first the question, prompted by his eighteenth novel, The Pole, sounds like a joke. The journalist Rian Malan, who visited Coetzee’s office at the University of Cape Town in the early 1990s, reported that the novelist didn’t smoke, drink, eat meat, or, except on very rare occasions, laugh. “It helps to have a piercing gaze,” Coetzee wrote in one of eight essays on Beckett, and his own author photographs show a man who, with his ironed shirts, unvainly swept-back hair, and eyes that would win any no-blinking competition, resembles a semi-retired notary public, or a mob boss who hasn’t got his hands dirty for decades. In his work, too, he offers little in the way of solace or solicitude, presenting a harsh world in parched prose.

HOW ROMANTIC IS J. M. COETZEE? At first the question, prompted by his eighteenth novel, The Pole, sounds like a joke. The journalist Rian Malan, who visited Coetzee’s office at the University of Cape Town in the early 1990s, reported that the novelist didn’t smoke, drink, eat meat, or, except on very rare occasions, laugh. “It helps to have a piercing gaze,” Coetzee wrote in one of eight essays on Beckett, and his own author photographs show a man who, with his ironed shirts, unvainly swept-back hair, and eyes that would win any no-blinking competition, resembles a semi-retired notary public, or a mob boss who hasn’t got his hands dirty for decades. In his work, too, he offers little in the way of solace or solicitude, presenting a harsh world in parched prose.

Coetzee is aware of this perception, and though he said Malan “does not know me” and was “not qualified” to talk about his character, he has also acknowledged that his taste for “spareness” is an “unattractive part of my makeup.”

more here.

Yorgos Lanthimos’s “Poor Things”

Kenneth Dillon at The Baffler:

Bella Baxter, the heroine of Poor Things in both the book and the film, often feels like one of those peculiar characters who appear in philosophy. In “Epiphenomenal Qualia,” for example, the Australian analytic philosopher Frank Jackson tells us about Mary, a brilliant scientist who “for whatever reason” has always lived inside a black and white room, learning everything about the world by watching a black and white television. What will happen, Jackson wonders, when we let her out—what knowledge will she gain when she sees the blue sky?

Bella Baxter, the heroine of Poor Things in both the book and the film, often feels like one of those peculiar characters who appear in philosophy. In “Epiphenomenal Qualia,” for example, the Australian analytic philosopher Frank Jackson tells us about Mary, a brilliant scientist who “for whatever reason” has always lived inside a black and white room, learning everything about the world by watching a black and white television. What will happen, Jackson wonders, when we let her out—what knowledge will she gain when she sees the blue sky?

Then there’s the American philosopher Judith Jarvis Thomson’s violinist. One morning you awake in a hospital bed, back to back with a famous violinist. He is ill; the Society of Music Lovers have kidnapped you and brought you here because only your blood can be used to save him.

more here.

Ari Aster & Yorgos Lanthimos l Directors on Directors

Sir Roger Deakins—An Englishman in LA

Hannah Gal in Quillette:

The sleek Leica gallery in Los Angeles is currently hosting a quintessentially English exhibition—39 arresting stills captured by Sir Roger Deakins, one of the most esteemed cinematographers of our time. Spanning five decades, the monochrome photographs are taken from Deakins’s 2021 book Byways—a title inspired by the time he spent as a young man during the early ’70s “wandering the byways” of north Devon in the southwest of England.

The boy from Torquay would go on to win Oscars, BAFTAS, and numerous other film-industry accolades for his work on some of the most beautifully crafted and iconic films in modern cinema.

More here.

What Are Farm Animals Thinking?

David Grimm in Science:

You’d never mistake a goat for a dog, but on an unseasonably warm afternoon in early September, I almost do. I’m in a red-brick barn in northern Germany, trying to keep my sanity amid some of the most unholy noises I’ve ever heard. Sixty Nigerian dwarf goats are taking turns crashing their horns against wooden stalls while unleashing a cacophony of bleats, groans, and retching wails that make it nearly impossible to hold a conversation. Then, amid the chaos, something remarkable happens. One of the animals raises her head over her enclosure and gazes pensively at me, her widely spaced eyes and odd, rectangular pupils seeking to make contact—and perhaps even connection.

You’d never mistake a goat for a dog, but on an unseasonably warm afternoon in early September, I almost do. I’m in a red-brick barn in northern Germany, trying to keep my sanity amid some of the most unholy noises I’ve ever heard. Sixty Nigerian dwarf goats are taking turns crashing their horns against wooden stalls while unleashing a cacophony of bleats, groans, and retching wails that make it nearly impossible to hold a conversation. Then, amid the chaos, something remarkable happens. One of the animals raises her head over her enclosure and gazes pensively at me, her widely spaced eyes and odd, rectangular pupils seeking to make contact—and perhaps even connection.

It’s a look we see in other humans, in our pets, and in our primate relatives. But not in animals raised for food. Or maybe we just haven’t been looking hard enough.

That’s the core idea here at the Research Institute for Farm Animal Biology (FBN), one of the world’s leading centers for investigating the minds of goats, pigs, and other livestock.

More here.