Bill Gates in Gates Notes:

For me, this will always be the year I became a grandparent. It will be the year I spent a lot of precious time with loved ones—whether on the pickleball court or over a rousing game of Settlers of Catan. And 2023 marked the first time I used artificial intelligence for work and other serious reasons, not just to mess around and create parody song lyrics for my friends.

For me, this will always be the year I became a grandparent. It will be the year I spent a lot of precious time with loved ones—whether on the pickleball court or over a rousing game of Settlers of Catan. And 2023 marked the first time I used artificial intelligence for work and other serious reasons, not just to mess around and create parody song lyrics for my friends.

This year gave us a glimpse of how AI will shape the future, and as 2023 comes to a close, I’m thinking more than ever about the world today’s young people will inherit. In last year’s letter, I wrote about how the prospect of becoming a grandparent made me reflect on the world my granddaughter will be born into. Now I’m thinking more about the world she will inherit and what it will be like decades from now, when her generation is in charge.

More here.

B

B Will an artificial intelligence (AI) superintelligence appear suddenly, or will scientists see it coming, and have a chance to warn the world? That’s a question that has received a lot of attention recently, with the rise of

Will an artificial intelligence (AI) superintelligence appear suddenly, or will scientists see it coming, and have a chance to warn the world? That’s a question that has received a lot of attention recently, with the rise of  In his new book Going Infinite: The Rise and Fall of a New Tycoon (2023), Michael Lewis has the difficult task of explaining why his subject, wunderkind Sam Bankman-Fried, co-founder of the multibillion-dollar cryptocurrency exchange FTX, who seemed tailor-made for the author’s patented oddball-outsider-disrupts-the-world shtick, was convicted for one of the biggest frauds in financial history. Like so many people both before and after crypto’s last big explosion in 2022, Lewis allows that he doesn’t know all that much about the underlying technologies, specifically blockchain, but is nevertheless compelled by the scene’s anarchic ambition. At one point, he throws up his hands and admits that crypto “often gets explained but somehow never stays explained.”

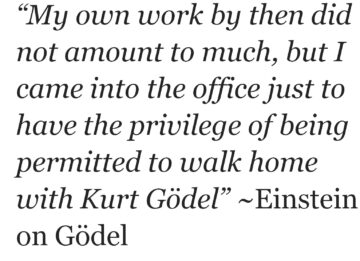

In his new book Going Infinite: The Rise and Fall of a New Tycoon (2023), Michael Lewis has the difficult task of explaining why his subject, wunderkind Sam Bankman-Fried, co-founder of the multibillion-dollar cryptocurrency exchange FTX, who seemed tailor-made for the author’s patented oddball-outsider-disrupts-the-world shtick, was convicted for one of the biggest frauds in financial history. Like so many people both before and after crypto’s last big explosion in 2022, Lewis allows that he doesn’t know all that much about the underlying technologies, specifically blockchain, but is nevertheless compelled by the scene’s anarchic ambition. At one point, he throws up his hands and admits that crypto “often gets explained but somehow never stays explained.” When Einstein talks of someone in the superlative, you know that person would have been beyond special. Indeed, Kurt Gödel was no ordinary man. Perhaps the greatest logician of all time, Gödel’s incompleteness theorems altered the very fabric of the epistemology of mathematical systems.

When Einstein talks of someone in the superlative, you know that person would have been beyond special. Indeed, Kurt Gödel was no ordinary man. Perhaps the greatest logician of all time, Gödel’s incompleteness theorems altered the very fabric of the epistemology of mathematical systems. In 1951, just six years after World War II, Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and West Germany signed the Treaty of Paris, establishing the European Coal and Steel Community.

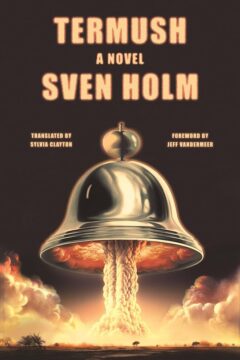

In 1951, just six years after World War II, Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and West Germany signed the Treaty of Paris, establishing the European Coal and Steel Community. Halfway through Sven Holm’s taut unfolding nightmare, Termush, the unnamed narrator encounters “ploughed-up and trampled gardens” where “stone creatures are the sole survivors.” Holm describes these statues as “curious forms, the bodies like great ill-defined blocks, designed more to evoke a sense of weight and mass than to suggest power in the muscles and sinews.” Later, a guest of the gated, walled hotel for the rich from which the novel takes its name relates a dream in which “light streamed out of every object; it shone through robes and skin and the flesh on the bones, the leaves on the trees … to reveal the innermost vulnerable marrow of people and plants.” The same could describe the novel, which accrues its strange effects via both this stricken, continuous revealing and the “curious forms” of a solid, impervious setting, in which the ordinary elements of our world come to seem alien through the lens of nuclear catastrophe.

Halfway through Sven Holm’s taut unfolding nightmare, Termush, the unnamed narrator encounters “ploughed-up and trampled gardens” where “stone creatures are the sole survivors.” Holm describes these statues as “curious forms, the bodies like great ill-defined blocks, designed more to evoke a sense of weight and mass than to suggest power in the muscles and sinews.” Later, a guest of the gated, walled hotel for the rich from which the novel takes its name relates a dream in which “light streamed out of every object; it shone through robes and skin and the flesh on the bones, the leaves on the trees … to reveal the innermost vulnerable marrow of people and plants.” The same could describe the novel, which accrues its strange effects via both this stricken, continuous revealing and the “curious forms” of a solid, impervious setting, in which the ordinary elements of our world come to seem alien through the lens of nuclear catastrophe. Novelist Hanif Kureishi sustained life-changing injuries when he collapsed and landed on his head on Boxing Day last year. Left without the use of his arms and legs, the award-winning writer of The Buddha of Suburbia and My Beautiful Laundrette has charted his experience in brutally-honest blog posts. He credits his sense of purpose to his relationship with his responsive readers. A year on, he joined BBC Radio 4’s Today programme as a guest editor and described the accident’s profound impact on his life.

Novelist Hanif Kureishi sustained life-changing injuries when he collapsed and landed on his head on Boxing Day last year. Left without the use of his arms and legs, the award-winning writer of The Buddha of Suburbia and My Beautiful Laundrette has charted his experience in brutally-honest blog posts. He credits his sense of purpose to his relationship with his responsive readers. A year on, he joined BBC Radio 4’s Today programme as a guest editor and described the accident’s profound impact on his life. Ozempic and other drugs like it have proven powerful at regulating blood sugar and driving weight loss. Now, scientists are exploring whether they might be just as transformative in treating a wide range of other conditions, from addiction and liver disease to a common cause of infertility. “It’s like a snowball that turned into an avalanche,” said Lindsay Allen, a health economist at Northwestern Medicine. As the drugs gain momentum, she said, “they’re leaving behind them this completely reshaped landscape.” Much of the research on other uses of semaglutide, the compound in Ozempic and Wegovy, and tirzepatide, the substance in Mounjaro and Zepbound, is only in the early stages. One of the biggest questions scientists are seeking to answer: Do the benefits of these drugs just boil down to weight loss? Or do they have other effects, like tamping down inflammation in the body or quieting the brain’s compulsive thoughts, that would make it possible to treat far more illnesses?

Ozempic and other drugs like it have proven powerful at regulating blood sugar and driving weight loss. Now, scientists are exploring whether they might be just as transformative in treating a wide range of other conditions, from addiction and liver disease to a common cause of infertility. “It’s like a snowball that turned into an avalanche,” said Lindsay Allen, a health economist at Northwestern Medicine. As the drugs gain momentum, she said, “they’re leaving behind them this completely reshaped landscape.” Much of the research on other uses of semaglutide, the compound in Ozempic and Wegovy, and tirzepatide, the substance in Mounjaro and Zepbound, is only in the early stages. One of the biggest questions scientists are seeking to answer: Do the benefits of these drugs just boil down to weight loss? Or do they have other effects, like tamping down inflammation in the body or quieting the brain’s compulsive thoughts, that would make it possible to treat far more illnesses?

Any time you walk outside, satellites may be watching you from space. There are currently

Any time you walk outside, satellites may be watching you from space. There are currently