Dahlia Lithwick in Slate:

The Supreme Court is on a collision course with itself, and it’s not clear that the justices even know it. We are now witnessing a five-car pileup of Trump–slash–Jan. 6 cases that will either be heard by the Supreme Court or land on their white marble steps in the coming weeks. The court has already agreed to hear the case of Joseph Fischer, the former Pennsylvania cop accused of taking part in the Jan. 6 storming of the Capitol and assaulting police officers, to determine the scope of prosecutions for obstructing an official proceeding. The court’s already flirting with hearing a direct appeal by special counsel Jack Smith to speedily resolve Trump’s claims to absolute immunity for his actions in attempting to overturn the 2020 election. And a game-changer of a case came out of the Colorado Supreme Court on Tuesday that would knock the former president off of the Republican primary ballot in that state as a consequence of his involvement in the insurrection attempt on Jan. 6, which would also critically apply to the general election ballot next November. That ruling has to be settled by the high court in order to forestall, or affirm, other states’ efforts to do the same thing. Potential appeals of gag orders in criminal suits and doofy immunity claims in the E. Jean Carroll suit are all also winging their way to Chief Justice John Roberts’ workstation, and it’s not even 2024 yet.

The Supreme Court is on a collision course with itself, and it’s not clear that the justices even know it. We are now witnessing a five-car pileup of Trump–slash–Jan. 6 cases that will either be heard by the Supreme Court or land on their white marble steps in the coming weeks. The court has already agreed to hear the case of Joseph Fischer, the former Pennsylvania cop accused of taking part in the Jan. 6 storming of the Capitol and assaulting police officers, to determine the scope of prosecutions for obstructing an official proceeding. The court’s already flirting with hearing a direct appeal by special counsel Jack Smith to speedily resolve Trump’s claims to absolute immunity for his actions in attempting to overturn the 2020 election. And a game-changer of a case came out of the Colorado Supreme Court on Tuesday that would knock the former president off of the Republican primary ballot in that state as a consequence of his involvement in the insurrection attempt on Jan. 6, which would also critically apply to the general election ballot next November. That ruling has to be settled by the high court in order to forestall, or affirm, other states’ efforts to do the same thing. Potential appeals of gag orders in criminal suits and doofy immunity claims in the E. Jean Carroll suit are all also winging their way to Chief Justice John Roberts’ workstation, and it’s not even 2024 yet.

More here.

T

T A well-known tourist attraction in Vanuatu is a large private compound near Port Vila on the island of Efate, belonging to local artist Aloï Pilioko. Situated beside Erakor Lagoon, the property — called Esnaar — was the shared studio home of Pilioko, a migrant from the island of Wallis in French Polynesia, and his French-Russian partner, the late Nicolaï Michoutouchkine, who passed away in 2010. After acquiring the property in 1961, the two artists pursued remarkable careers together, traveling, collecting, exhibiting, and making “Oceanic art” all over the world. In the 1990s, the property was converted into a tourist attraction with outdoor pavilions housing displays of travel memorabilia, a shop where they sold a line of hand-painted clothing, and ethnographic works from the collection distributed around the gardens and on display inside their studio homes.

A well-known tourist attraction in Vanuatu is a large private compound near Port Vila on the island of Efate, belonging to local artist Aloï Pilioko. Situated beside Erakor Lagoon, the property — called Esnaar — was the shared studio home of Pilioko, a migrant from the island of Wallis in French Polynesia, and his French-Russian partner, the late Nicolaï Michoutouchkine, who passed away in 2010. After acquiring the property in 1961, the two artists pursued remarkable careers together, traveling, collecting, exhibiting, and making “Oceanic art” all over the world. In the 1990s, the property was converted into a tourist attraction with outdoor pavilions housing displays of travel memorabilia, a shop where they sold a line of hand-painted clothing, and ethnographic works from the collection distributed around the gardens and on display inside their studio homes. “By the way, how are you managing with the 100-copy collection?”

“By the way, how are you managing with the 100-copy collection?” 2023 will be the year with the highest emissions ever recorded, according to new projections from the

2023 will be the year with the highest emissions ever recorded, according to new projections from the  Donald Trump is an astoundingly dangerous candidate for president. He is a pathological liar, with clear authoritarian instincts. Were he elected to a second term, the damage he would do to the institutions of our republic is profound. His reelection would be worse than any political event in the history of America — save the decision of South Carolina to launch the Civil War.

Donald Trump is an astoundingly dangerous candidate for president. He is a pathological liar, with clear authoritarian instincts. Were he elected to a second term, the damage he would do to the institutions of our republic is profound. His reelection would be worse than any political event in the history of America — save the decision of South Carolina to launch the Civil War. I remember where I was when Edward Said died.

I remember where I was when Edward Said died.

Exactly. I love to point out philosophical mistakes made by those scientists who think philosophy is a throwaway. In the areas of science that I am interested in—the nature of consciousness, the nature of reality, the nature of explanation—they often fall into the old traps that philosophers have learned about by falling into those traps themselves. There is no learning without making mistakes, but then you have to learn from your mistakes.

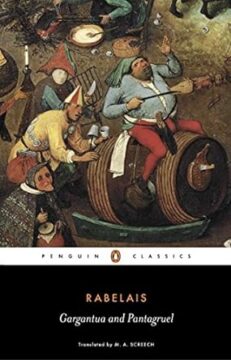

Exactly. I love to point out philosophical mistakes made by those scientists who think philosophy is a throwaway. In the areas of science that I am interested in—the nature of consciousness, the nature of reality, the nature of explanation—they often fall into the old traps that philosophers have learned about by falling into those traps themselves. There is no learning without making mistakes, but then you have to learn from your mistakes. To try to understand the whole of Rabelais or his writing is the work of a lifetime—I am not sure if Rabelais himself would think such a lifetime well spent—but even a passing acquaintance with this odd fellow is certainly worthwhile. There is a mystery here, of the finest vintage; every time I pick up the blue brick called Gargantua and Pantagruel, I find myself asking, in the midst of chuckles, how can something so stupid have turned literature upside down? Why does this book matter at all?

To try to understand the whole of Rabelais or his writing is the work of a lifetime—I am not sure if Rabelais himself would think such a lifetime well spent—but even a passing acquaintance with this odd fellow is certainly worthwhile. There is a mystery here, of the finest vintage; every time I pick up the blue brick called Gargantua and Pantagruel, I find myself asking, in the midst of chuckles, how can something so stupid have turned literature upside down? Why does this book matter at all?  When Luana Marques was growing up in Brazil, life was not easy. Her parents had her when they were very young, and they didn’t know how to take care of themselves, much less their children. Drugs and alcohol were also a problem. “Between the many instances of domestic violence, I often felt scared, wondering when something bad would happen next,” she says. She lived

When Luana Marques was growing up in Brazil, life was not easy. Her parents had her when they were very young, and they didn’t know how to take care of themselves, much less their children. Drugs and alcohol were also a problem. “Between the many instances of domestic violence, I often felt scared, wondering when something bad would happen next,” she says. She lived  Obesity plays out as a private struggle and a public health crisis. In the United States, about 70% of adults are affected by excess weight, and in Europe that number is more than half. The stigma against fat can be crushing; its risks, life-threatening. Defined as a body mass index of at least 30, obesity is thought to power type 2 diabetes, heart disease, arthritis, fatty liver disease, and certain cancers. Yet drug treatments for obesity have a sorry past, one often intertwined with social pressure to lose weight and the widespread belief that excess weight reflects weak willpower. From “rainbow diet pills” packed with amphetamines and diuretics that were marketed to women beginning in the 1940s, to the 1990s rise and fall of fen-phen, which triggered catastrophic heart and lung conditions, history is beset by failures to find safe, successful weight loss drugs.

Obesity plays out as a private struggle and a public health crisis. In the United States, about 70% of adults are affected by excess weight, and in Europe that number is more than half. The stigma against fat can be crushing; its risks, life-threatening. Defined as a body mass index of at least 30, obesity is thought to power type 2 diabetes, heart disease, arthritis, fatty liver disease, and certain cancers. Yet drug treatments for obesity have a sorry past, one often intertwined with social pressure to lose weight and the widespread belief that excess weight reflects weak willpower. From “rainbow diet pills” packed with amphetamines and diuretics that were marketed to women beginning in the 1940s, to the 1990s rise and fall of fen-phen, which triggered catastrophic heart and lung conditions, history is beset by failures to find safe, successful weight loss drugs.