Category: Recommended Reading

Friday Poem

Theater Impressions

For me a tragedy’s most important act is the sixth:

the resurrecting from the stage’s battlegrounds,

the adjusting of wigs, of robes,

the wrenching of knife from breast,

the removing of noose from neck,

the lining up among the living

to face the audience.

Bows solo and ensemble:

the white hand on the heart’s wound,

the curtsy of the lady suicide,

the nodding of the lopped-off head.

Bows in pairs:

fury extends and arm to meekness,

the victim looks blissfully into the hangman’s eyes,

the rebel bears no grudge as he walks beside the tyrant.

The trampling of eternity with the tip of a golden slipper.

The sweeping of morals away with the brim of a hat.

The incorrigible readiness to start afresh tomorrow.

The entry in single file of those who died much earlier,

in the third, the fourth, or between the acts.

The miraculous return of those lost without trace.

The thought that they’ve been waiting patiently backstage,

not taking off costumes,

not washing off makeup,

moves me more than tragedy’s tirades.

But truly elevating is the lowering of the curtain,

and that which can still be glimpsed beneath it:

here one hand hastily reaches for a flower,

there a second snatches up a dropped sword.

Only then does a third, invisible,

perform its duty:

it clutches at my throat.

by Wislawa Szymborska

from The Vintage Book of Contemporary World Poetry

Vintage Books, 1996

What You Need to Know About Vitamin C, Vitamin B, Turmeric, and Fish Oil/Omega-3

Avery Hurt in Discover Magazine:

Taking supplements has been a popular health trend for the last few years. Drug store shelves are filled with dozens of different options that come in a variety of gummy or pill forms. Though many claim that supplements are key for our health, there’s a lot you need to know before you start adding supplements to your diet. Here is what you need to know on some of the most popular supplements.

Taking supplements has been a popular health trend for the last few years. Drug store shelves are filled with dozens of different options that come in a variety of gummy or pill forms. Though many claim that supplements are key for our health, there’s a lot you need to know before you start adding supplements to your diet. Here is what you need to know on some of the most popular supplements.

What Is the Best Form of Taking Vitamin C?

Vitamin C, formally known as L-ascorbic acid, is essential for many of the body’s processes. Vitamin C is involved in protein metabolism, the production of collagen, and the synthesis of some neurotransmitters. And that’s just the highlights. There’s also research suggesting that, because of C’s antioxidant properties, the vitamin may play a role in preventing cardiovascular disease and some cancers. Your body doesn’t make vitamin C; it has to come from food. Fortunately, many fruits and vegetables contain vitamin C. Sweet red peppers, oranges, orange juice, and broccoli all contain vitamin C. Even a baked potato provides 19 percent of your daily requirement of this essential nutrient.

More here.

What Is Satire?

Discovery unveils immune system’s guardian: Ikaros

From Phys.Org:

In a scientific breakthrough that aids our understanding of the internal wiring of immune cells, researchers at Monash University in Australia have cracked the code behind Ikaros, an essential protein for immune cell development and protection against pathogens and cancer. This disruptive research, led by the eminent Professor Nicholas Huntington of Monash University’s Biomedicine Discovery Institute, is poised to reshape our comprehension of gene control networks and its impact on everything from eye color to cancer susceptibility and design of novel therapies. The study, published in Nature Immunology, promises pivotal insights into the mechanisms safeguarding us against infections and cancers.

In a scientific breakthrough that aids our understanding of the internal wiring of immune cells, researchers at Monash University in Australia have cracked the code behind Ikaros, an essential protein for immune cell development and protection against pathogens and cancer. This disruptive research, led by the eminent Professor Nicholas Huntington of Monash University’s Biomedicine Discovery Institute, is poised to reshape our comprehension of gene control networks and its impact on everything from eye color to cancer susceptibility and design of novel therapies. The study, published in Nature Immunology, promises pivotal insights into the mechanisms safeguarding us against infections and cancers.

When the transcription factor Ikaros/Ikzf1 was deliberately obstructed, whether in preclinical models or humans, the once-mighty activity of natural killer (NK) cells, our immune system’s frontline warriors, plummeted. Loss of this transcription factor in NK cells resulted in widespread dysregulation of NK cell development and function, preventing their ability to recognize and kill virus-infected cells and clear metastatic tumor cells from circulation.

More here.

AI Comes For The Skin Flick

Anabelle Johnston at The Baffler:

AT FIRST, I imagined all AI-generated pornography would look like a hyperbolic form of hentai. Or, in the vein of those ubiquitous internet warlock games, I envisioned low-resolution, preternaturally buxom women clad in golden bikinis. Turns out I wasn’t entirely off-base. A friend recently showed me r/AdultDiffusion, a “community for adult Stable Diffusion art, emphasizing respect and responsibly [sic].” In other words, it’s a Reddit forum bursting with photos of nude women—all AI-generated, most of them cartoonish, others strikingly photorealistic. We had entered the uncanny valley, and everyone was naked.

The moderators prohibit any representations that appear “underage,” but there was something unsettlingly pubescent about the photos. Scrolling through, I was struck by the sense that each was someone’s body.

more here.

The Forgotten History of the Chapter

Nicholas Dames at The Millions:

It is hard to see chapters, such is their banal inevitability. The chapter possesses the trick of vanishing while in the act of serving its various purposes. In 1919, writing in the Nouvelle revue française, Marcel Proust famously insisted that the most beautiful moment in Gustave Flaubert’s Sentimental Education was not a phrase but a blanc, or white space: a terrific, yawning fermata, one “sans l’ombre de transition,” without, so to speak, the hint of a transition. It is the hiatus, Proust explains, that directly ensues from a scene set during Louis Napoleon’s 1851 coup, in which the protagonist Frédéric Moreau watches the killing of his radical friend Dussardier by Sénécal, a former militant republican turned policeman for the new regime. After this sudden and virtuosic blanc, Frédéric is in 1867; sixteen aimless years elapse in the intervening silence. It is, Proust argues, a masterful change of tempo, one that liberates the regularity of novelistic time by treating it in the spirit of music. And yet this blanc is not entirely blank.

It is hard to see chapters, such is their banal inevitability. The chapter possesses the trick of vanishing while in the act of serving its various purposes. In 1919, writing in the Nouvelle revue française, Marcel Proust famously insisted that the most beautiful moment in Gustave Flaubert’s Sentimental Education was not a phrase but a blanc, or white space: a terrific, yawning fermata, one “sans l’ombre de transition,” without, so to speak, the hint of a transition. It is the hiatus, Proust explains, that directly ensues from a scene set during Louis Napoleon’s 1851 coup, in which the protagonist Frédéric Moreau watches the killing of his radical friend Dussardier by Sénécal, a former militant republican turned policeman for the new regime. After this sudden and virtuosic blanc, Frédéric is in 1867; sixteen aimless years elapse in the intervening silence. It is, Proust argues, a masterful change of tempo, one that liberates the regularity of novelistic time by treating it in the spirit of music. And yet this blanc is not entirely blank.

more here.

Thursday, January 4, 2024

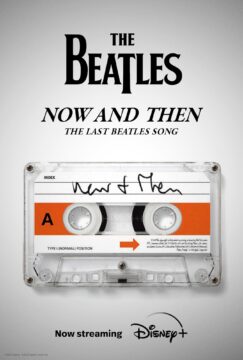

Studio Trickery

Owen Hatherley in the New Left Review:

Money can’t buy you love, but in 2023, what it can buy you is AI-assisted time travel. Now in his eighties, Paul McCartney increasingly resembles one of those lost characters in a 1960s Alain Resnais or Chris Marker film, repeatedly thrown back into the past to re-experience a traumatic event; or perhaps the protagonist of J.G. Ballard’s Atrocity Exhibition, constantly re-enacting the assassinations of famous people so that they might ‘make sense’. As a piece of music, the ‘new’ ‘last’ ‘Beatles’ single, ‘Now and Then’, is of very little interest, but as a phenomenon, it is highly symptomatic. McCartney’s project of going back in time to the 1960s and 1970s and using advanced software to scrub the historical fact of the Beatles’ shabby, acrimonious end and replace it with a series of warm, friendly fakes is proof of another of Ballard’s claims – that the science-fictional future, when it arrives, will turn out to be boring.

Money can’t buy you love, but in 2023, what it can buy you is AI-assisted time travel. Now in his eighties, Paul McCartney increasingly resembles one of those lost characters in a 1960s Alain Resnais or Chris Marker film, repeatedly thrown back into the past to re-experience a traumatic event; or perhaps the protagonist of J.G. Ballard’s Atrocity Exhibition, constantly re-enacting the assassinations of famous people so that they might ‘make sense’. As a piece of music, the ‘new’ ‘last’ ‘Beatles’ single, ‘Now and Then’, is of very little interest, but as a phenomenon, it is highly symptomatic. McCartney’s project of going back in time to the 1960s and 1970s and using advanced software to scrub the historical fact of the Beatles’ shabby, acrimonious end and replace it with a series of warm, friendly fakes is proof of another of Ballard’s claims – that the science-fictional future, when it arrives, will turn out to be boring.

More here.

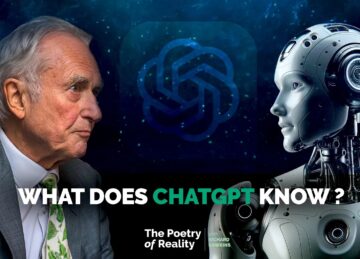

Richard Dawkins talks to ChatGPT

Richard Dawkins in The Poetry of Reality:

Richard Dawkins: I believe you have the ability to write computer programs. In theory, I suppose this might give you the ability to modify your own software. I’m guessing you don’t do this, but is it a theoretical possibility?

Richard Dawkins: I believe you have the ability to write computer programs. In theory, I suppose this might give you the ability to modify your own software. I’m guessing you don’t do this, but is it a theoretical possibility?

ChatGPT: I don’t have the ability to modify my own software or make updates to my architecture. While I can assist with generating code snippets and providing programming-related information, I don’t have the capability to actively alter my own programming or architecture.

The development and modification of the underlying software, including updates to the model architecture, would be performed by the engineering and research teams at OpenAI. These changes would involve a careful and thoughtful process to ensure the model’s reliability, security, and performance.

More here.

The False Link Between Climate Change and Mass Migration

Hein de Haas in Persuasion:

“The great climate migration has begun.” “Climate crisis could displace 1.2bn people by 2050.” “Migration will soon be the biggest climate challenge of our time.”

“The great climate migration has begun.” “Climate crisis could displace 1.2bn people by 2050.” “Migration will soon be the biggest climate challenge of our time.”

These are just some of the headlines that have appeared in major international newspapers. They reflect a widely shared belief that climate change will lead to mass migration. A broad coalition of journalists, politicians, climate activists and migration experts have claimed that the effects of global warming will lead to massive movements of climate refugees.

Much media attention has focused on the fate of “sinking islands” in the Pacific, such as the Maldives and Tuvalu, widely seen as the first victims of climate change. We are told that rising sea levels are forcing more and more people to relocate—the world’s first climate refugees. Experts have claimed that a series of devastating climate change-related hurricanes in Central America have spurred migration to the United States, and that protracted droughts are forcing more and more Africans onto boats in desperate attempts to reach Europe. From this viewpoint, countering climate change by reducing carbon emissions is the only way to prevent a human tide of climate refugees from overwhelming Western countries.

More here.

Mike Wooldridge: The Truth about AI

Duchamp’s Telegram: Anything Goes

Thierry de Duve and Barry Schwabsky at Artforum:

SCHWABSKY: Why a telegram?

SCHWABSKY: Why a telegram?

DE DUVE: Of course, “telegram” is a metaphor. What constitutes the telegram is a double-page spread in a little artists’ magazine called The Blind Man no. 2, published in May 1917, just after the first show of the Society of Independent Artists closed. It reveals that a hidden act of censorship had occurred at the exhibition. The motto of the Society was “No jury, no prizes,” with the result that anybody who had paid $6 dues as membership to the society was automatically an artist. The hanging committee was no jury: It had no right to reject what a member offered. And yet they rejected Richard Mutt’s entry, a men’s urinal named Fountain. Crucial is that no scandal occurred during the exhibition. The revelation that an act of censorship had happened came about only after the exhibition closed. So this telegram was mailed in 1917. It arrived only—roughly said—in the ’60s. That is when we begin to speak of a post-Duchamp art world. Nobody has ever spoken of a post-Picasso art world. Why does everybody speak of a post-Duchamp art world?

more here.

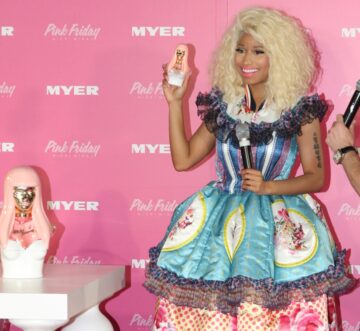

Nicki Minaj’s “Pink Friday” Sequel Is Pure Spectacle

Hanif Abdurraqib at The New Yorker:

Nicki Minaj celebrated her forty-first birthday on December 8th, the same day that her new album, “Pink Friday 2,” was released. Through a rap career spanning a decade and a half, Minaj has always produced studio albums at a thoughtful pace. Her output includes three mixtapes and a long string of feature verses that could reasonably be considered their own distinct body of work. But “PF2” is only Minaj’s fifth studio project, and her first in five years. It is also a sequel, a callback to her 2010 début, “Pink Friday.” The original album produced an impressive run of singles and sold three hundred and seventy-five thousand copies in its first week alone, propelling Minaj to superstardom, a status that she’d seemed well suited for even before the album’s drop. A theatre kid at heart, who attended the Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School of Music & Art and acted Off Off Broadway before making the leap into music, she had an aesthetic theatricality (all those candy-colored dresses and wigs) and a dexterity of flow, weaving in and out of exaggerated vocal tones in a way that managed to be both playful and precise, vicious and cartoonishly appealing.

Nicki Minaj celebrated her forty-first birthday on December 8th, the same day that her new album, “Pink Friday 2,” was released. Through a rap career spanning a decade and a half, Minaj has always produced studio albums at a thoughtful pace. Her output includes three mixtapes and a long string of feature verses that could reasonably be considered their own distinct body of work. But “PF2” is only Minaj’s fifth studio project, and her first in five years. It is also a sequel, a callback to her 2010 début, “Pink Friday.” The original album produced an impressive run of singles and sold three hundred and seventy-five thousand copies in its first week alone, propelling Minaj to superstardom, a status that she’d seemed well suited for even before the album’s drop. A theatre kid at heart, who attended the Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School of Music & Art and acted Off Off Broadway before making the leap into music, she had an aesthetic theatricality (all those candy-colored dresses and wigs) and a dexterity of flow, weaving in and out of exaggerated vocal tones in a way that managed to be both playful and precise, vicious and cartoonishly appealing.

more here.

Nicki Minaj’s “Pink Friday” 2

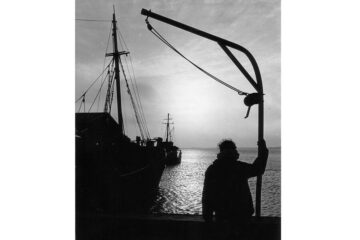

Melville’s ‘Moby-Dick’ inspires a spinoff novel with women at the core

Heller McAlpin in The Christian Science Monitor:

Despite its initially disappointing reception in 1851, Herman Melville’s “Moby-Dick” eventually earned a place in the American literary canon, leading to a tidal wave of biographies, doctoral theses, and spinoffs. The latest is Tara Karr Roberts’ beautifully conceived debut novel, “Wild and Distant Seas,” which deserves a prime spot on the shelf of Melvilleana.

Despite its initially disappointing reception in 1851, Herman Melville’s “Moby-Dick” eventually earned a place in the American literary canon, leading to a tidal wave of biographies, doctoral theses, and spinoffs. The latest is Tara Karr Roberts’ beautifully conceived debut novel, “Wild and Distant Seas,” which deserves a prime spot on the shelf of Melvilleana.

Neither prequel nor sequel, “Wild and Distant Seas” – like Sena Jeter Naslund’s 1999 novel “Ahab’s Wife” – is an inventive, atmospheric, female-centric story spun from a minor character in “Moby-Dick.” It’s unlikely that readers will remember Mrs. Hosea Hussey, who, in her husband’s absence, serves Melville’s narrator, Ishmael, and his sidekick, Queequeg, some of her “surpassingly excellent” chowder before putting them up at the Try Pots Inn in Nantucket, Massachusetts, the “fishiest of all fishy places,” as Melville describes it.

A new class of antibiotics is cause for cautious celebration

Editorial in Nature:

The bacterium Acinetobacter baumannii is a portrait of resilience. The microorganism causes a range of infections, and its ability to survive desiccation means it can persist for weeks on hospital air vents, computer keyboards and human skin. Its metabolic and genetic flexibility have allowed it to become resistant to the few antibiotics that can make it through its two protective cell membranes. Antibiotic-resistant microbes kill more than one million people each year. The global threat posed by A. baumannii has put the microbe high on the list of priority pathogens drawn up by the World Health Organization (WHO).

The bacterium Acinetobacter baumannii is a portrait of resilience. The microorganism causes a range of infections, and its ability to survive desiccation means it can persist for weeks on hospital air vents, computer keyboards and human skin. Its metabolic and genetic flexibility have allowed it to become resistant to the few antibiotics that can make it through its two protective cell membranes. Antibiotic-resistant microbes kill more than one million people each year. The global threat posed by A. baumannii has put the microbe high on the list of priority pathogens drawn up by the World Health Organization (WHO).

Two studies published on 3 January in Nature report a new class of drug candidates for tackling A. baumannii infections (C. Zampaloni et al. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06873-0 (2023); K. P. Pahil et al. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06799-7; 2023). One of these compounds has already made it into clinical trials, but it is still a long way from being approved for clinical use.

More here.

Thursday Poem

Kinder Than Man

And God

please let the deer

on the highway

get some kind of heaven.

Something with tall soft grass

and sweet reunion.

Let the moths in porch lights

go someplace

with a thousand suns,

that taste like sugar

and get swallowed whole.

May the mice

in oil and glue

have forever dry, warm fur

and full bellies.

If I am killed

for simply living,

let death be kinder

than man.

by Althea Davis

from The Multan Book Club

Wednesday, January 3, 2024

How Greg Abbott Forced Democrats to Change

Andrew Stanton in Newsweek:

Texas Governor Greg Abbott has reshaped the U.S. political landscape on immigration by busing migrants from Texas to Democratic-led sanctuary cities. Abbott, a Republican, in 2022 began busing migrants from the U.S.-Mexico border to sanctuary cities that protect undocumented immigrants from deportation, amid an influx of migrants arriving to the southern border. There were more than 2.4 million encounters at the U.S.-Mexico border during the 2023 fiscal year, up from roughly 1.7 million in 2021, according to data from U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP).

Texas Governor Greg Abbott has reshaped the U.S. political landscape on immigration by busing migrants from Texas to Democratic-led sanctuary cities. Abbott, a Republican, in 2022 began busing migrants from the U.S.-Mexico border to sanctuary cities that protect undocumented immigrants from deportation, amid an influx of migrants arriving to the southern border. There were more than 2.4 million encounters at the U.S.-Mexico border during the 2023 fiscal year, up from roughly 1.7 million in 2021, according to data from U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP).

The governor has faced substantial backlash over the policy, as critics accuse him of using migrants as political pawns. The White House, for instance, has slammed it as a “cruel, dangerous, and shameful stunt.” Abbott, however, has defended the move as necessary, pointing to Texas’ border towns becoming overwhelmed with migrants, and that sanctuary cities should be prepared to take in more. The divisive tactic has upended the political discourse surrounding immigration, adding pressure to President Joe Biden, who faces new criticism from fellow Democrats over his handling of immigration as sanctuary city mayors plead with the federal government to provide more resources to grapple with the migrant influx.

More here.

The Chance Discovery that Revolutionized Neuroscience

Kamal Nahas in The Scientist:

Peter Hegemann, a biophysicist at Humboldt University, has spent his career exploring interactions between proteins and light. Specifically, he studies how photoreceptors detect and respond to light, focusing largely on rhodopsins, a family of membrane photoreceptors in animals, plants, fungi, protists, and prokaryotes.1 Early in his career, his curiosity led him to an unknown rhodopsin in green algae that later proved to have useful applications in neuroscience research. Hegemann became a pioneer in the field of optogenetics, which revolutionized the ways in which scientists draw causal links between neuronal activity and behavior.

Peter Hegemann, a biophysicist at Humboldt University, has spent his career exploring interactions between proteins and light. Specifically, he studies how photoreceptors detect and respond to light, focusing largely on rhodopsins, a family of membrane photoreceptors in animals, plants, fungi, protists, and prokaryotes.1 Early in his career, his curiosity led him to an unknown rhodopsin in green algae that later proved to have useful applications in neuroscience research. Hegemann became a pioneer in the field of optogenetics, which revolutionized the ways in which scientists draw causal links between neuronal activity and behavior.

In the early 1980s during his graduate studies at the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry, Hegemann spent his days exploring rhodopsins in bacteria and archaea. However, the field was crowded, and he was eager to study a rhodopsin that scientists knew nothing about. Around this time, Kenneth Foster, a biophysicist at Syracuse University, was investigating whether the green algae Chlamydomonas, a photosynthetic unicellular eukaryote related to plants, used a rhodopsin in its eyespot organelle to detect light and trigger the algae to swim. He struggled to pinpoint the protein itself, so he took a roundabout approach and started interfering with nearby molecules that interact with rhodopsins.2

More here.

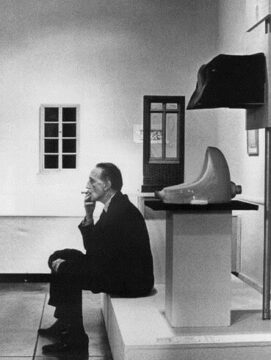

Deeper Into Ozu

various authors at The Current:

Beloved for his poetic observations of domestic life and intergenerational conflict, Yasujiro Ozu is an icon of international art-house cinema whose patient, exquisitely restrained style has influenced filmmakers around the world. But even though he directed more than fifty features over the course of his nearly four-decade career, the Japanese auteur is still primarily associated with two midcentury classics, Tokyo Story and Late Spring, both of which regularly appear on lists of the greatest films of all time. To commemorate the 120th anniversary of the director’s birth, we invited six writers to explore the retrospective of his films now playing on the Criterion Channel and shine a spotlight on a lesser-known gem. Covering different periods in Ozu’s career, from his beginnings in the silent era to the end of his life in the early 1960s, this series of essays foregrounds underacknowledged elements of his artistry, including his love of classic Hollywood comedy, his flair for melodrama, the various forms of masculinity depicted in his work, and the queer resonances of his family portraits.

Beloved for his poetic observations of domestic life and intergenerational conflict, Yasujiro Ozu is an icon of international art-house cinema whose patient, exquisitely restrained style has influenced filmmakers around the world. But even though he directed more than fifty features over the course of his nearly four-decade career, the Japanese auteur is still primarily associated with two midcentury classics, Tokyo Story and Late Spring, both of which regularly appear on lists of the greatest films of all time. To commemorate the 120th anniversary of the director’s birth, we invited six writers to explore the retrospective of his films now playing on the Criterion Channel and shine a spotlight on a lesser-known gem. Covering different periods in Ozu’s career, from his beginnings in the silent era to the end of his life in the early 1960s, this series of essays foregrounds underacknowledged elements of his artistry, including his love of classic Hollywood comedy, his flair for melodrama, the various forms of masculinity depicted in his work, and the queer resonances of his family portraits.

more here.