Category: Recommended Reading

Israelis and Palestinians warring over a homeland is far from unique

Monica Duffy Toft in The Conversation:

The ongoing horrors unfolding in Israel and Gaza have deep-rooted origins that stem from a complex and contested question: Who has rights to the same territory?

The ongoing horrors unfolding in Israel and Gaza have deep-rooted origins that stem from a complex and contested question: Who has rights to the same territory?

I am a scholar of international affairs, as well as territory and nationalism. Territory has been a central cause of conflict throughout history.

Today, Israelis and Palestinians both claim the same swath of land as their own. Each group has its own historical narratives, its own names for the territory – Israel or Palestine, depending on whom you ask – and many people from each group believe strongly that sharing the land is impossible.

Palestinians and Israelis also look to this same land as a way to define their identities and protect their futures.

More here.

Why I Am Not a Christian by Bertrand Russell (1927)

Saturday, December 23, 2023

Oh, Mr Hitchens!

Laura Kipnis in Critical Quarterly:

In 2010, when a book I’d written called How to Become a Scandal was going to press, my editor contacted Christopher to ask for a blurb. He sent back three choices, the first of which read, ‘Laura Kipnis promised me a blowjob if I endorsed her latest triumph, which I hereby warmly and devotedly do.’ I’m sure it says nothing good about me that I found this funny, especially since using it would have so perfectly – and devilishly – enacted the premise of the book. Though generally no prig, sadly my editor insisted we go with the more conventional third option (the second was a double entendre about a now mostly forgotten Republican senator caught in a clumsy men’s room encounter). She did forward me their subsequent correspondence: ‘Christopher – you are a scream!’ she’d written back, to which he responded, ‘Yeah? Well a lot depends on which one she picks.’

I can be as humourless as the next leftwing feminist but for some reason Christopher’s, what to call it – lasciviousness? antiquarianism? – amused more than offended me, though his public anti-abortion stance was noxious and, one suspects, hypocritical. Colour me surprised if that particular edict was upheld in practice. In any case, I never thought of him as someone you’d go to for instruction on feminism, and increasingly not on any political question, yet it was perplexingly hard to hold his bad politics against him.

More here.

The War on Hospitals

Joelle M. Abi-Rached in Boston Review:

The face of the ongoing onslaught on Gaza has no doubt been Dr. Hammam Alloh, the thirty-six-year-old Palestinian nephrologist at northern Gaza’s Al-Shifa Hospital who refused to evacuate it when it was invaded by Israeli troops. “And if I go, who treats my patients?” he said in an October 31 interview. “We are not animals. We have the right to receive proper healthcare,” he added. Two weeks later, Alloh was killed by an Israeli airstrike, along with his father, brother-in-law, and father-in-law.

Alloh’s use of the word “animals” was certainly not lost on viewers. Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant had used that same language on October 9 when he announced a “complete siege” on Gaza, labeling its residents as “human animals.” Hamas’s attacks on October 7 would predictably generate a violent military reaction from Israel. But this Israeli campaign in Gaza, a strip of land where more than 80 percent of its population lived in poverty even before October 7, has been of a different character entirely than any previous ones. This onslaught has featured direct attacks on hospitals and the intentional undermining of the entire health care system: shelling, the killing and arresting of health care personnel, the direct and indirect killing of hundreds of patients, underprovision or complete lack of proper medical care, and unwarranted suffering for thousands of patients due to shortages in basic medications, water, food, and fuel. The attacks have made clear that the repression of Palestinian rights now has a new feature: the systematic destruction of the very institutions that sustain life.

More here.

Anarcho-Capitalism

Maria Haro Sly in Phenomenal World:

Maria Haro Sly in Phenomenal World:

Since the early 2000s, Argentine development finance has undergone a profound transformation. Amid cyclical debt defaults and endless negotiations with Western investors and the IMF, Chinese overseas investment loans have slowly crept to the fore. Between 2007 and 2020, Argentina received $10.65 billion in investment from Chinese companies, concentrated in the energy, mining, and financial sectors. Today, Argentina is the fourth-largest recipient of Chinese loans in the region, securing around $17 billion in total. These loans have primarily supported transportation infrastructure, energy projects, and the enhancement of Argentine exports. In 2022, President Alberto Fernández agreed to open financing lines with China totaling nearly $23 billion through the Strategic Dialogue for Economic Cooperation and Coordination (DECCE) and Belt and Road Initiative, though the latter is still pending activation.

It’s within this changing borrowing landscape that Javier Milei, the self-defined “first true free-trade reformer and libertarian president in the history of the world,” has been elected. Milei won the ballot against the former Minister of Finance, Sergio Massa, in a country with 140 percent inflation rate and plummeting exports thanks to a drought that resulted in a $19 billion loss, nearly 3 percent of Argentina’s GDP.

Economically, Milei raises a sense of déjà vu reminiscent of neoliberal figures from the 1970s, 1990s, and the Macri era. His political party and cabinet are drawn from earlier administrations, with figures like Ricardo Bussi (son of the dictator and governor of the Tucuman Province), and members from Menem’s administration, including Menem’s nephew, Martín Menem, as president of the Senate. Notably, a significant number of former ministers from Macri’s government—Patricia Bullrich, Luis Caputo, Santiago Bausili, among others—have also joined Milei’s cabinet.

More here.

When Philosophers Become Therapists

Nick Romeo in The New Yorker:

Around five years ago, David—a pseudonym—realized that he was fighting with his girlfriend all the time. On their first date, he had told her that he hoped to have sex with a thousand women before he died. They’d eventually agreed to have an exclusive relationship, but monogamy remained a source of tension. “I always used to tell her how much it bothered me,” he recalled. “I was an asshole.” An Israeli man now in his mid-thirties, David felt conflicted about other life issues. Did he want kids? How much should he prioritize making money? In his twenties, he’d tried psychotherapy several times; he would see a therapist for a few months, grow frustrated, stop, then repeat the cycle. He developed a theory. The therapists he saw wanted to help him become better adjusted given his current world view—but perhaps his world view was wrong. He wanted to examine how defensible his values were in the first place.

Around five years ago, David—a pseudonym—realized that he was fighting with his girlfriend all the time. On their first date, he had told her that he hoped to have sex with a thousand women before he died. They’d eventually agreed to have an exclusive relationship, but monogamy remained a source of tension. “I always used to tell her how much it bothered me,” he recalled. “I was an asshole.” An Israeli man now in his mid-thirties, David felt conflicted about other life issues. Did he want kids? How much should he prioritize making money? In his twenties, he’d tried psychotherapy several times; he would see a therapist for a few months, grow frustrated, stop, then repeat the cycle. He developed a theory. The therapists he saw wanted to help him become better adjusted given his current world view—but perhaps his world view was wrong. He wanted to examine how defensible his values were in the first place.

One day, a housemate showed him a book called “Philosophy, Humor, and the Human Condition,” by the French Israeli philosopher Lydia Amir. Amir, the housemate explained, was his cousin. In addition to teaching part-time at Tufts University, she offered “philosophical counselling” to private clients. David had never heard of philosophical counselling. But over the next few weeks he read and enjoyed Amir’s book. He watched an episode of an Israeli current-affairs TV show, “London and Kirschenbaum,” in which she debated the merits of philosophical counselling with the hosts. “She actually looked like she enjoyed it when they tried to take her down,” David said. He decided to contact her, and they arranged some online sessions.

More here.

A delightful look back at how the Renaissance changed beauty standards

Becca Rothfeld in The Washington Post:

Is beautification always a capitulation to sexist pressures? Or can it be a means of self-expression? These are the perennial questions that Jill Burke takes up in “How to Be a Renaissance Woman: The Untold History of Beauty and Female Creativity.” They were also subjects of heated debate during the Renaissance, when some women chastised their peers for vanity and others maintained that beautification practices allowed them a measure of agency.

More here.

Lou Reed: The King of New York

David Shariatmadari at The Guardian:

“King of New York” was the epithet given to him by David Bowie, an obsessive Velvets fan who rescued Reed’s lacklustre solo career by producing Transformer, which spawned his biggest hit, Walk on the Wild Side. It’s also the title of Will Hermes’s meticulous yet vivid new biography, the first to draw on the archive donated to the New York Public Library by Reed’s widow Laurie Anderson. As in his 2011 book Love Goes to Buildings on Fire, about the city’s mid-70s musical landscape, Hermes expertly conjures the different scenes Reed inhabited, placing him amid a rich cast of collaborators, friends and lovers.

“King of New York” was the epithet given to him by David Bowie, an obsessive Velvets fan who rescued Reed’s lacklustre solo career by producing Transformer, which spawned his biggest hit, Walk on the Wild Side. It’s also the title of Will Hermes’s meticulous yet vivid new biography, the first to draw on the archive donated to the New York Public Library by Reed’s widow Laurie Anderson. As in his 2011 book Love Goes to Buildings on Fire, about the city’s mid-70s musical landscape, Hermes expertly conjures the different scenes Reed inhabited, placing him amid a rich cast of collaborators, friends and lovers.

There’s a sense that he’s updating Reed for a new generation, particularly as a prophet of queer liberation and gender nonconformity. This isn’t a stretch: one of his best songs, 1969’s Candy Says, is an achingly poignant evocation of gender dysphoria, among other things. On 1972’s Make Up, three years after the Stonewall riots, he proclaimed “Now we’re coming out, out of our closets / Out on the streets”.

more here.

Velvet Underground Documentary

The Essential Henry James

Lauren Christensen at the NYT:

Forget everything you’ve ever heard about less being more, about economy of syntax, about the read-between-the-lines profundity of wide-margined, double-spaced “spare prose.” To read a paragraph by Henry James — a single one can sprawl across pages — is to luxuriate in linguistic excess.

Forget everything you’ve ever heard about less being more, about economy of syntax, about the read-between-the-lines profundity of wide-margined, double-spaced “spare prose.” To read a paragraph by Henry James — a single one can sprawl across pages — is to luxuriate in linguistic excess.

An American expatriate who spent his adulthood in England, James (1843-1916) was the patron saint of exquisite verbosity; of circuitous, compulsively sub-claused sentences that contain all the twists and adventures his story lines lack. Reading the prodigious body of fiction he produced over four decades, between 1871 and 1911, you get the sense he lost himself so deeply in his recurrent themes — the innocence of America versus the experience and depravity of Europe, the psychological richness of everyday life — that he couldn’t help carrying on.

This applied to his nonfiction, too. James didn’t just write novels; he wrote about writing novels, obsessing over his craft the way his characters obsess over the minutiae of their lives.

more here.

Saturday Poem

It was Beginning Winter

It was beginning winter

An in-between time,

The landscape still partly brown;

The bones of weeds kept swinging in the wind

Above the blue snow.

It was beginning winter.

The light moved slowly over the frozen field,

Over the dry seed crowns,

The beautiful surviving bones

Swinging in the wind.

Light traveled over the wide field;

stayed.

The weeds stopped swinging.

The mind moved, not alone,

Through the clear air, in the silence.

Was it light?

Was it light within?

Was it light within light?

Stillness becoming alive,

Yet still?

A lively understandable spirit

One entertained you.

It will come again.

Be still.

Wait.

Friday, December 22, 2023

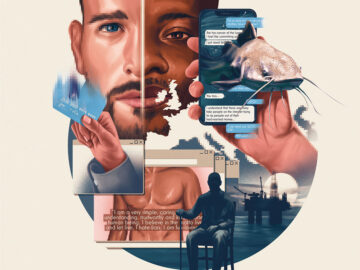

How one detective took on an international network of romance fraudsters

Stuart McGurk in The New Statesman:

Police officers are often the last to know when someone is being conned. A worried son might spot unusual payments on his elderly father’s bank statement. A concerned friend will do a reverse-image search on a suspiciously good-looking dating-app match. A fraudster will run out of excuses as to why they can’t meet. A horrible realisation will dawn and a report will be filed.

Police officers are often the last to know when someone is being conned. A worried son might spot unusual payments on his elderly father’s bank statement. A concerned friend will do a reverse-image search on a suspiciously good-looking dating-app match. A fraudster will run out of excuses as to why they can’t meet. A horrible realisation will dawn and a report will be filed.

More here.

On Two New Books About Slime

Mariella Rudi in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

Goo. Gunk. Gloop. Gak. By its own definition, slime is hard to grasp. As an object of disgust, it represents our fears and stigmas, the unknown Other. As a toy or sight gag, it’s a silly plaything. It’s easy to forget that slime permeates every living being on Earth, that, like the cosmos or fungi, slime’s existence is vital to our own, a biological imperative as much as oxygen or sunlight. Nebulous and omnipresent, deathless and primordial, slime is an essential link between nonliving matter and the first life that developed in the ocean 3.6 billion years ago. Slime molds are at least millions of years old and can thrive in outer space. The granddaddy of all mankind, slime is everywhere. It’s also easy to miss, which helps explain why we’re often so afraid of it.

Goo. Gunk. Gloop. Gak. By its own definition, slime is hard to grasp. As an object of disgust, it represents our fears and stigmas, the unknown Other. As a toy or sight gag, it’s a silly plaything. It’s easy to forget that slime permeates every living being on Earth, that, like the cosmos or fungi, slime’s existence is vital to our own, a biological imperative as much as oxygen or sunlight. Nebulous and omnipresent, deathless and primordial, slime is an essential link between nonliving matter and the first life that developed in the ocean 3.6 billion years ago. Slime molds are at least millions of years old and can thrive in outer space. The granddaddy of all mankind, slime is everywhere. It’s also easy to miss, which helps explain why we’re often so afraid of it.

Capturing the world’s most misunderstood, slippery substance is thus no easy task. Two books published in the last year have tried: Susanne Wedlich’s Slime: A Natural History, and File Under: Slime by Christopher Michlig. These books ooze praise thickened by arguments as far-flung and mutable as their shared subject. Both trace a sleek line through art, fashion, literature, film, science, commerce, and beyond, offering mature takes on a childhood fixation.

More here.

To build a better world, stop chasing economic growth

Robert Costanza in Nature:

The past year has given many of us reason to pause. We are losing in a race to prevent planetary tipping points — the climate is changing faster than expected, and humanity has already breached six of the nine sustainable planetary boundaries (for biodiversity loss; climate, freshwater and land-system change; biogeochemical flows; and novel entities)1. Summer Antarctic sea ice shrank to its lowest recorded extent in 2023 (see go.nature.com/4f86req), a year that is on track to be the warmest on record (see go.nature.com/4f9ykdj).

The past year has given many of us reason to pause. We are losing in a race to prevent planetary tipping points — the climate is changing faster than expected, and humanity has already breached six of the nine sustainable planetary boundaries (for biodiversity loss; climate, freshwater and land-system change; biogeochemical flows; and novel entities)1. Summer Antarctic sea ice shrank to its lowest recorded extent in 2023 (see go.nature.com/4f86req), a year that is on track to be the warmest on record (see go.nature.com/4f9ykdj).

People around the world recognize that life is not getting any better. As wars rage, runaway inequality and political polarization are eroding societies’ sense of cohesion. Eight individuals owned more than the poorest 50% of the world’s population, according to an Oxfam report in 20172. Levels of anxiety, depression and burnout are rocketing. Full-time employees are unable to pay rent and must turn to extra part-time work to make ends meet, while employers cut staff and increase workloads.

More here.

David Deutsch & Steven Pinker – AGI, P(Doom), & The Enemies of Progress

Friday Poem

Advent

and the Angel of Attention

nudges my shoulder

see how above

the fallen gold leaves

of the apple tree

the last bees

hum about stalks

of sea-lavender,

drinking the last

sweetness of the last

year

to make

the first honey

for what will be

born again

Saved by Infinite Jest

Mala Chatterjee in aeon:

In the surreal aftermath of my suicide attempt and amid the haze of my own processing, my best friend visited me in the hospital with a (soft-bound and thus mental-patient-safe) copy of David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest under his arm. It was the spring of 2021. A couple months earlier, I had slipped in a tub, suffered a concussion, and triggered my first episode of major depression, and those had been the most difficult months of my life.

In the surreal aftermath of my suicide attempt and amid the haze of my own processing, my best friend visited me in the hospital with a (soft-bound and thus mental-patient-safe) copy of David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest under his arm. It was the spring of 2021. A couple months earlier, I had slipped in a tub, suffered a concussion, and triggered my first episode of major depression, and those had been the most difficult months of my life.

Though a lifelong ‘striver’ and ‘high achiever’, nothing I’ve ever done was harder than waging that war against myself while catatonic on that Brooklyn sofa. This was an inarticulable and so alienating war, one during which, at every moment, it was excruciating and terrifying to exist at all. I thought I knew the extent of my own mind’s capacity to torture itself, to hurt me, and what this thing we call depression can really be like. But I had been wrong.

For anyone who hasn’t experienced it at its worst, I now think it is psychologically impossible to imagine. It may even prove impossible for those who have experienced to still remember it after the fact, just as someone who temporarily perceives a fourth dimension wouldn’t really, fully remember what it was like once the perception is lost, only facets of the larger, unfathomable thing.

So maybe I can’t really remember, either: but I can recall thinking again and again these staggered reflections I’m writing now.

More here.

The Year in Biology

Thursday, December 21, 2023

The Supreme Court Did This to Itself

Dahlia Lithwick in Slate:

The Supreme Court is on a collision course with itself, and it’s not clear that the justices even know it. We are now witnessing a five-car pileup of Trump–slash–Jan. 6 cases that will either be heard by the Supreme Court or land on their white marble steps in the coming weeks. The court has already agreed to hear the case of Joseph Fischer, the former Pennsylvania cop accused of taking part in the Jan. 6 storming of the Capitol and assaulting police officers, to determine the scope of prosecutions for obstructing an official proceeding. The court’s already flirting with hearing a direct appeal by special counsel Jack Smith to speedily resolve Trump’s claims to absolute immunity for his actions in attempting to overturn the 2020 election. And a game-changer of a case came out of the Colorado Supreme Court on Tuesday that would knock the former president off of the Republican primary ballot in that state as a consequence of his involvement in the insurrection attempt on Jan. 6, which would also critically apply to the general election ballot next November. That ruling has to be settled by the high court in order to forestall, or affirm, other states’ efforts to do the same thing. Potential appeals of gag orders in criminal suits and doofy immunity claims in the E. Jean Carroll suit are all also winging their way to Chief Justice John Roberts’ workstation, and it’s not even 2024 yet.

The Supreme Court is on a collision course with itself, and it’s not clear that the justices even know it. We are now witnessing a five-car pileup of Trump–slash–Jan. 6 cases that will either be heard by the Supreme Court or land on their white marble steps in the coming weeks. The court has already agreed to hear the case of Joseph Fischer, the former Pennsylvania cop accused of taking part in the Jan. 6 storming of the Capitol and assaulting police officers, to determine the scope of prosecutions for obstructing an official proceeding. The court’s already flirting with hearing a direct appeal by special counsel Jack Smith to speedily resolve Trump’s claims to absolute immunity for his actions in attempting to overturn the 2020 election. And a game-changer of a case came out of the Colorado Supreme Court on Tuesday that would knock the former president off of the Republican primary ballot in that state as a consequence of his involvement in the insurrection attempt on Jan. 6, which would also critically apply to the general election ballot next November. That ruling has to be settled by the high court in order to forestall, or affirm, other states’ efforts to do the same thing. Potential appeals of gag orders in criminal suits and doofy immunity claims in the E. Jean Carroll suit are all also winging their way to Chief Justice John Roberts’ workstation, and it’s not even 2024 yet.

More here.

The cosmetics entrepreneur Helena Rubinstein once observed, “There are no ugly women, only lazy ones.” The kind of beauty she had in mind is an ambivalent gift. On the one hand, it is not confined to the biologically blessed but available to everyone; on the other, it is a hard-earned prize, a product of ritualistic and often painstaking devotions at the mirror. Is this sort of beauty worth pursuing? Some feminist thinkers have bashed it as a superficial distraction. “Taught from infancy that beauty is woman’s sceptre, the mind shapes itself to the body, and roaming round its gilt cage, only seeks to adorn its prison,” Mary Wollstonecraft wrote disdainfully in 1792. Yet there is a tinge of misogyny to the familiar accusation that cosmetic projects are fluffy trivialities. Perhaps there is more truth (and more respect) to be found in the view of the novelist Henry James, who once described a female character’s flair for fashion as a form of “genius.”

The cosmetics entrepreneur Helena Rubinstein once observed, “There are no ugly women, only lazy ones.” The kind of beauty she had in mind is an ambivalent gift. On the one hand, it is not confined to the biologically blessed but available to everyone; on the other, it is a hard-earned prize, a product of ritualistic and often painstaking devotions at the mirror. Is this sort of beauty worth pursuing? Some feminist thinkers have bashed it as a superficial distraction. “Taught from infancy that beauty is woman’s sceptre, the mind shapes itself to the body, and roaming round its gilt cage, only seeks to adorn its prison,” Mary Wollstonecraft wrote disdainfully in 1792. Yet there is a tinge of misogyny to the familiar accusation that cosmetic projects are fluffy trivialities. Perhaps there is more truth (and more respect) to be found in the view of the novelist Henry James, who once described a female character’s flair for fashion as a form of “genius.”