Joelle M. Abi-Rached in Boston Review:

The face of the ongoing onslaught on Gaza has no doubt been Dr. Hammam Alloh, the thirty-six-year-old Palestinian nephrologist at northern Gaza’s Al-Shifa Hospital who refused to evacuate it when it was invaded by Israeli troops. “And if I go, who treats my patients?” he said in an October 31 interview. “We are not animals. We have the right to receive proper healthcare,” he added. Two weeks later, Alloh was killed by an Israeli airstrike, along with his father, brother-in-law, and father-in-law.

Alloh’s use of the word “animals” was certainly not lost on viewers. Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant had used that same language on October 9 when he announced a “complete siege” on Gaza, labeling its residents as “human animals.” Hamas’s attacks on October 7 would predictably generate a violent military reaction from Israel. But this Israeli campaign in Gaza, a strip of land where more than 80 percent of its population lived in poverty even before October 7, has been of a different character entirely than any previous ones. This onslaught has featured direct attacks on hospitals and the intentional undermining of the entire health care system: shelling, the killing and arresting of health care personnel, the direct and indirect killing of hundreds of patients, underprovision or complete lack of proper medical care, and unwarranted suffering for thousands of patients due to shortages in basic medications, water, food, and fuel. The attacks have made clear that the repression of Palestinian rights now has a new feature: the systematic destruction of the very institutions that sustain life.

More here.

DURING A HISTORY

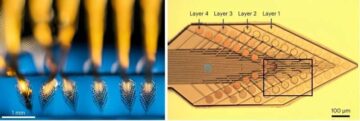

DURING A HISTORY Recording the activity of large populations of single neurons in the brain over long periods of time is crucial to further our understanding of neural circuits, to enable novel medical device-based therapies and, in the future, for brain–computer interfaces requiring high-resolution electrophysiological information. But today there is a tradeoff between how much high-resolution information an implanted device can measure and how long it can maintain recording or stimulation performances. Rigid, silicon implants with many sensors, can collect a lot of information but can’t stay in the body for very long. Flexible, smaller devices are less intrusive and can last longer in the brain but only provide a fraction of the available neural information.

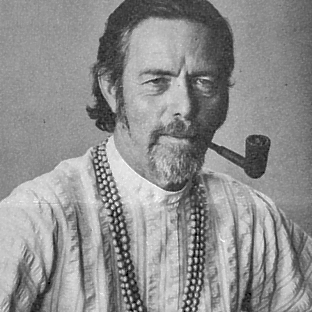

Recording the activity of large populations of single neurons in the brain over long periods of time is crucial to further our understanding of neural circuits, to enable novel medical device-based therapies and, in the future, for brain–computer interfaces requiring high-resolution electrophysiological information. But today there is a tradeoff between how much high-resolution information an implanted device can measure and how long it can maintain recording or stimulation performances. Rigid, silicon implants with many sensors, can collect a lot of information but can’t stay in the body for very long. Flexible, smaller devices are less intrusive and can last longer in the brain but only provide a fraction of the available neural information. For anyone who has seen or heard Watts at his best – courtesy, perhaps, of his podcast talks – ‘immeasurably alive’ is quite a good description of the man himself. It is easy to see how a basic understanding of God in these terms might have resonated with him. Watts also had moments when the sheer wonder of life around him made it feel as though it was not merely ‘there’, as brute fact, but was being poured out with extraordinary generosity. It seemed ‘given’, convincing Watts that there must be a giver and filling him with the desire to say ‘thank you’. He found backing for all of this in the writings of the 14th-century German theologian Meister Eckhart and the 6th-century Greek author Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite. It was there, too, in the ‘I-Thou’ thought of the modern Jewish philosopher

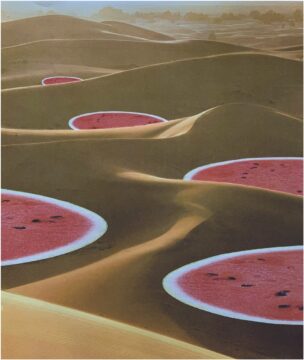

For anyone who has seen or heard Watts at his best – courtesy, perhaps, of his podcast talks – ‘immeasurably alive’ is quite a good description of the man himself. It is easy to see how a basic understanding of God in these terms might have resonated with him. Watts also had moments when the sheer wonder of life around him made it feel as though it was not merely ‘there’, as brute fact, but was being poured out with extraordinary generosity. It seemed ‘given’, convincing Watts that there must be a giver and filling him with the desire to say ‘thank you’. He found backing for all of this in the writings of the 14th-century German theologian Meister Eckhart and the 6th-century Greek author Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite. It was there, too, in the ‘I-Thou’ thought of the modern Jewish philosopher  The air conditioner was malfunctioning. When I bought the car used in January, the owner said she had just fixed it, but here I was on a steamy August day on the Atlantic coast of Senegal, with the vents pouring hot air into the already hot car. So, it was my imminent dehydration talking when I skidded to a stop in front of a roadside fruit seller’s table. I was once told by a grandmother, who lives in my seaside village but grew up in the northern dry regions where the Senegal River winds across a crispy and prickly savanna not far from the great desert, about a watermelon varietal called beref, which is cultivated mostly for its seeds but also serves as a kind of water reserve.

The air conditioner was malfunctioning. When I bought the car used in January, the owner said she had just fixed it, but here I was on a steamy August day on the Atlantic coast of Senegal, with the vents pouring hot air into the already hot car. So, it was my imminent dehydration talking when I skidded to a stop in front of a roadside fruit seller’s table. I was once told by a grandmother, who lives in my seaside village but grew up in the northern dry regions where the Senegal River winds across a crispy and prickly savanna not far from the great desert, about a watermelon varietal called beref, which is cultivated mostly for its seeds but also serves as a kind of water reserve. Why is giving birth so dangerous despite millions of years of evolution?

Why is giving birth so dangerous despite millions of years of evolution? “If China takes Taiwan, they will turn the world off, potentially,” Donald Trump

“If China takes Taiwan, they will turn the world off, potentially,” Donald Trump  DE MONCHAUX

DE MONCHAUX Rarely have so many Lebanese turned out on the streets to demand wholesale political change as when they began their self-declared “October Revolution” of 2019. And rarely has there been so little positive result.

Rarely have so many Lebanese turned out on the streets to demand wholesale political change as when they began their self-declared “October Revolution” of 2019. And rarely has there been so little positive result. Longevity is complicated

Longevity is complicated …incoherence can hold between mental states of various types: for example, between beliefs, preferences, intentions, or mixtures of more than one of these types. In all cases, though, it’s crucial that the defect is in the combination of states, not necessarily in any of them taken individually. There’s nothing wrong with preferring chocolate ice cream to vanilla, or preferring vanilla to strawberry, or preferring strawberry to chocolate; but there is something very strange about having all of these preferences together.

…incoherence can hold between mental states of various types: for example, between beliefs, preferences, intentions, or mixtures of more than one of these types. In all cases, though, it’s crucial that the defect is in the combination of states, not necessarily in any of them taken individually. There’s nothing wrong with preferring chocolate ice cream to vanilla, or preferring vanilla to strawberry, or preferring strawberry to chocolate; but there is something very strange about having all of these preferences together.