Mychal Denzel Smith in Harper’s Magazine:

Toward the end of the Obama presidency, the work of James Baldwin began to enjoy a renaissance that was both much overdue and comfortless. Baldwin stands as one of the greatest American writers of the twentieth century, and any celebration of his work is more than welcome. But it was less a reveling than a panic. The eight years of the first black president were giving way to some of the most blatant and vitriolic displays of racism in decades, while the shooting deaths of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, and others too numerous to list sparked a movement in defense of black lives. In Baldwin, people found a voice from the past so relevant that he seemed prophetic.

Toward the end of the Obama presidency, the work of James Baldwin began to enjoy a renaissance that was both much overdue and comfortless. Baldwin stands as one of the greatest American writers of the twentieth century, and any celebration of his work is more than welcome. But it was less a reveling than a panic. The eight years of the first black president were giving way to some of the most blatant and vitriolic displays of racism in decades, while the shooting deaths of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, and others too numerous to list sparked a movement in defense of black lives. In Baldwin, people found a voice from the past so relevant that he seemed prophetic.

More than any other writer, Baldwin has become the model for black public-intellectual work. The role of the public intellectual is to proffer new ideas, encourage deep thinking, challenge norms, and model forms of debate that enrich our discourse. For black intellectuals, that work has revolved around the persistence of white supremacy. Black abolitionists, ministers, and poets theorized freedom and exposed the hypocrisy of American democracy throughout the period of slavery. After emancipation, black colleges began training generations of scholars, writers, and artists who broadened black intellectual life. They helped build movements toward racial justice during the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, whether through pathbreaking journalism, research, or activism.

More here. (Note: In honor of Black History Month, at least one post will be devoted to its 2024 theme of “African Americans and the Arts” throughout the month of February)

H

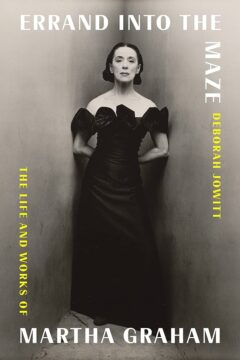

H The choreographer’s collaborations were top-notch: the sculptor Isamu Noguchi; the composer Samuel Barber; and the designer Halston. Learning how she drew inspiration from so many disparate cultures (Greek, Indigenous, biblical) — with occasional gross insensitivity — one begins to realize that the term “modern dance,” like “classical music,” is if not a misnomer, then a massive oversimplification.

The choreographer’s collaborations were top-notch: the sculptor Isamu Noguchi; the composer Samuel Barber; and the designer Halston. Learning how she drew inspiration from so many disparate cultures (Greek, Indigenous, biblical) — with occasional gross insensitivity — one begins to realize that the term “modern dance,” like “classical music,” is if not a misnomer, then a massive oversimplification. F

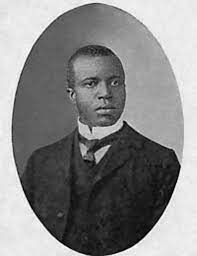

F Ragtime, propulsively syncopated musical style, one forerunner of

Ragtime, propulsively syncopated musical style, one forerunner of  The tunes and the beats of

The tunes and the beats of  Depending on the kind of sensor they’ve been armed with, drones can do a lot more than spray chemicals. Some can analyze the terrain for weeds, check moisture levels, assess for signs of pest infestation, suggest field planning, determine crop health, and even create a nutrient map of the growing harvest.

Depending on the kind of sensor they’ve been armed with, drones can do a lot more than spray chemicals. Some can analyze the terrain for weeds, check moisture levels, assess for signs of pest infestation, suggest field planning, determine crop health, and even create a nutrient map of the growing harvest. Psychology researcher Eli Finkel and his colleagues have suggested that moral judgment

Psychology researcher Eli Finkel and his colleagues have suggested that moral judgment