Shelly Fan in Singularity Hub:

Longevity is complicated. Multiple factors influence how fast our tissues and organs age, such as genetic typos, inflammation, epigenetic changes, and metabolic problems. But there is a throughline: Decades of work in multiple species have found that cutting calories and increasing exercise keeps multiple organ functions young as we age. Many of the benefits come from interactions between the brain and body. The brain doesn’t exist in a vat. Although protected by a very selective barrier that only lets certain molecules in, neurons react to blood components which bypass the barrier to alter their functions—for example, retaining learning and memory functions in old age.

Longevity is complicated. Multiple factors influence how fast our tissues and organs age, such as genetic typos, inflammation, epigenetic changes, and metabolic problems. But there is a throughline: Decades of work in multiple species have found that cutting calories and increasing exercise keeps multiple organ functions young as we age. Many of the benefits come from interactions between the brain and body. The brain doesn’t exist in a vat. Although protected by a very selective barrier that only lets certain molecules in, neurons react to blood components which bypass the barrier to alter their functions—for example, retaining learning and memory functions in old age.

Recent studies have increasingly pinpointed multiple communication channels between the brain and muscles, skeleton, and liver. After exercise, for example, proteins released by the body alter brain functions, boosting learning and memory in aging mice and, in some cases, elderly humans. When these communication channels break down, it triggers health problems associated with aging and limits life span and health span (the number of healthy years).

The brain-body connection works both ways. Tucked deep in the base of the brain, the hypothalamus regulates myriad hormones to modify bodily functions. With its hormonal secretions, the brain region sends directions to a wide range of organs including the liver, muscle, intestines, and fatty tissue, changing their behavior with age. Often dubbed the “control center of aging,” the hypothalamus has long been a target for longevity researchers.

More here.

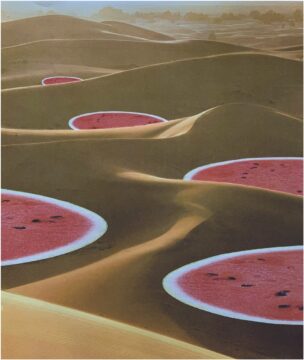

The air conditioner was malfunctioning. When I bought the car used in January, the owner said she had just fixed it, but here I was on a steamy August day on the Atlantic coast of Senegal, with the vents pouring hot air into the already hot car. So, it was my imminent dehydration talking when I skidded to a stop in front of a roadside fruit seller’s table. I was once told by a grandmother, who lives in my seaside village but grew up in the northern dry regions where the Senegal River winds across a crispy and prickly savanna not far from the great desert, about a watermelon varietal called beref, which is cultivated mostly for its seeds but also serves as a kind of water reserve.

The air conditioner was malfunctioning. When I bought the car used in January, the owner said she had just fixed it, but here I was on a steamy August day on the Atlantic coast of Senegal, with the vents pouring hot air into the already hot car. So, it was my imminent dehydration talking when I skidded to a stop in front of a roadside fruit seller’s table. I was once told by a grandmother, who lives in my seaside village but grew up in the northern dry regions where the Senegal River winds across a crispy and prickly savanna not far from the great desert, about a watermelon varietal called beref, which is cultivated mostly for its seeds but also serves as a kind of water reserve.

Why is giving birth so dangerous despite millions of years of evolution?

Why is giving birth so dangerous despite millions of years of evolution? “If China takes Taiwan, they will turn the world off, potentially,” Donald Trump

“If China takes Taiwan, they will turn the world off, potentially,” Donald Trump  DE MONCHAUX

DE MONCHAUX Rarely have so many Lebanese turned out on the streets to demand wholesale political change as when they began their self-declared “October Revolution” of 2019. And rarely has there been so little positive result.

Rarely have so many Lebanese turned out on the streets to demand wholesale political change as when they began their self-declared “October Revolution” of 2019. And rarely has there been so little positive result. Longevity is complicated

Longevity is complicated …incoherence can hold between mental states of various types: for example, between beliefs, preferences, intentions, or mixtures of more than one of these types. In all cases, though, it’s crucial that the defect is in the combination of states, not necessarily in any of them taken individually. There’s nothing wrong with preferring chocolate ice cream to vanilla, or preferring vanilla to strawberry, or preferring strawberry to chocolate; but there is something very strange about having all of these preferences together.

…incoherence can hold between mental states of various types: for example, between beliefs, preferences, intentions, or mixtures of more than one of these types. In all cases, though, it’s crucial that the defect is in the combination of states, not necessarily in any of them taken individually. There’s nothing wrong with preferring chocolate ice cream to vanilla, or preferring vanilla to strawberry, or preferring strawberry to chocolate; but there is something very strange about having all of these preferences together. Despite millennia of arguments, the question of whether we have free will or not remains unresolved. Last year October, two neurobiologists stepped into the fray, giving me the chance to dip my toes into the free-will debate. I just reviewed Robert Sapolsky’s

Despite millennia of arguments, the question of whether we have free will or not remains unresolved. Last year October, two neurobiologists stepped into the fray, giving me the chance to dip my toes into the free-will debate. I just reviewed Robert Sapolsky’s  There seem to be two words in the air at the moment, that keep popping up in articles and finding their way into American political discourse. One is “sleepwalking.” The other is “homelessness.”

There seem to be two words in the air at the moment, that keep popping up in articles and finding their way into American political discourse. One is “sleepwalking.” The other is “homelessness.” The prestigious Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI) in Boston, Massachusetts,

The prestigious Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI) in Boston, Massachusetts,

There are many places in L.A. you can go to think about the city, and my own favorite has become the Los Angeles River, which looks like an outsize concrete sewer and is most famous for being forgotten. The L.A. River flows fifty-one miles through the heart of L.A. County. It is enjoying herculean efforts to revitalize it, and yet commuters who have driven over it five days a week for ten years cannot tell you where it is. Along the river, the midpoint lies roughly at the confluence with the Arroyo Seco, near Dodger Stadium downtown. L.A. was founded near here in 1781: this area offers the most reliable aboveground supply of freshwater in the L.A. basin. It’s a miserable spot now, a trash-strewn wasteland of empty lots, steel fences, and railroad tracks beneath a tangle of freeway overpasses: it looks like a Blade Runner set that a crew disassembled and then put back together wrong. It’s not the most scenic spot to visit the river but may be the finest place on the river to think about L.A.

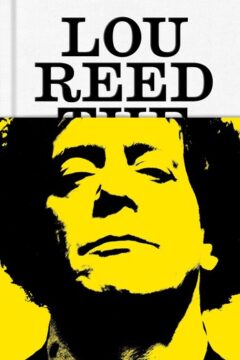

There are many places in L.A. you can go to think about the city, and my own favorite has become the Los Angeles River, which looks like an outsize concrete sewer and is most famous for being forgotten. The L.A. River flows fifty-one miles through the heart of L.A. County. It is enjoying herculean efforts to revitalize it, and yet commuters who have driven over it five days a week for ten years cannot tell you where it is. Along the river, the midpoint lies roughly at the confluence with the Arroyo Seco, near Dodger Stadium downtown. L.A. was founded near here in 1781: this area offers the most reliable aboveground supply of freshwater in the L.A. basin. It’s a miserable spot now, a trash-strewn wasteland of empty lots, steel fences, and railroad tracks beneath a tangle of freeway overpasses: it looks like a Blade Runner set that a crew disassembled and then put back together wrong. It’s not the most scenic spot to visit the river but may be the finest place on the river to think about L.A. BEYOND AN OLDER SIBLING’S headphones wringing the sweet, distorted fuzz of the Velvet Underground out and into my ears, my second most notable encounter with Lou Reed was in the pages of the Lester Bangs anthology Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung, which has a whole section dedicated to Bangs and his relentless sparring with Reed. A book within a book, almost. There are two interviews that would, today, seem alarming in both their approach and the nature of their candidness, with Bangs demeaning Reed’s pal David Bowie, Reed taking the bait, Bangs shouting that Reed is full of shit. The interviews go on like this, Bangs and Reed clashing, arguing loudly, or with an on-page ferocity that occasionally veered into affection. Reed clamors on about the drugs he consumes to survive, Bangs takes Reed to task for his songwriting’s increasing laziness. Ultimately, in the essays Bangs wrote about Reed, without Reed in the room, we find that these clashes, brutal and invasive as they might have seemed in the interview form, were born out of a writer being present with a subject he admired deeply, growing frustrated that the mythology he’d made of the subject wasn’t being manifested in the person he had been so fascinated by. This frustration inspired some terribly cruel writing that eventually led to a permanent falling-out between the two.

BEYOND AN OLDER SIBLING’S headphones wringing the sweet, distorted fuzz of the Velvet Underground out and into my ears, my second most notable encounter with Lou Reed was in the pages of the Lester Bangs anthology Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung, which has a whole section dedicated to Bangs and his relentless sparring with Reed. A book within a book, almost. There are two interviews that would, today, seem alarming in both their approach and the nature of their candidness, with Bangs demeaning Reed’s pal David Bowie, Reed taking the bait, Bangs shouting that Reed is full of shit. The interviews go on like this, Bangs and Reed clashing, arguing loudly, or with an on-page ferocity that occasionally veered into affection. Reed clamors on about the drugs he consumes to survive, Bangs takes Reed to task for his songwriting’s increasing laziness. Ultimately, in the essays Bangs wrote about Reed, without Reed in the room, we find that these clashes, brutal and invasive as they might have seemed in the interview form, were born out of a writer being present with a subject he admired deeply, growing frustrated that the mythology he’d made of the subject wasn’t being manifested in the person he had been so fascinated by. This frustration inspired some terribly cruel writing that eventually led to a permanent falling-out between the two. In the aftermath of a disaster, our immediate reaction is often to search for some person to blame. Authorities frequently vow to “find those responsible” and “hold them to account,” as though disasters happen only when some grinning mischief-maker slams a big red button labeled “press for catastrophe.” That’s not to say that negligence ought to go unpunished. Sometimes there really is a malefactor to blame, but equally often there isn’t, and the result is that normal people who just made a mistake are caught up in the dragnet of vengeance, like the famous 2009 case of six Italian seismologists who were charged for failing to predict a deadly earthquake. But when that happens, what is actually accomplished? Has anything been made better? Or have we simply kicked the can down the road?

In the aftermath of a disaster, our immediate reaction is often to search for some person to blame. Authorities frequently vow to “find those responsible” and “hold them to account,” as though disasters happen only when some grinning mischief-maker slams a big red button labeled “press for catastrophe.” That’s not to say that negligence ought to go unpunished. Sometimes there really is a malefactor to blame, but equally often there isn’t, and the result is that normal people who just made a mistake are caught up in the dragnet of vengeance, like the famous 2009 case of six Italian seismologists who were charged for failing to predict a deadly earthquake. But when that happens, what is actually accomplished? Has anything been made better? Or have we simply kicked the can down the road?