Yael Friedman at the LARB:

EARLY ON IN Wim Wenders’s new documentary Anselm, we hear the whispers of Anselm Kiefer’s famous headless female sculptures. “We may be the nameless and forgotten ones,” they whisper, “but we don’t forget a thing.” These full-bodied specters haunt us in the way only Kiefer’s art can. His body of work interrogates myth and memory, wrestling with Germany’s past in ways that helped form the foundation of its postwar present.

EARLY ON IN Wim Wenders’s new documentary Anselm, we hear the whispers of Anselm Kiefer’s famous headless female sculptures. “We may be the nameless and forgotten ones,” they whisper, “but we don’t forget a thing.” These full-bodied specters haunt us in the way only Kiefer’s art can. His body of work interrogates myth and memory, wrestling with Germany’s past in ways that helped form the foundation of its postwar present.

Both Wenders and Kiefer, two of Germany’s most iconic artists, were born in 1945, into the still-smoldering ruins of the war. Their engagement with the heaviness of history, and the “great silence” of the adults after the war, took dramatically different forms. Kiefer confronted it relentlessly, even bombastically, while Wenders has been guided by it more obliquely. In my recent conversation with Wenders, the filmmaker acknowledged that the two of them “had a very different approach—I wanted to leave it behind, and Anselm wanted to dig into it and put his finger on it. And that is also why I felt we had something to do together.”

more here.

T

T To write about Lou Reed is to fight with Lou Reed. It is difficult to say, however, who started what, and there is more than a little evidence that the sourness of rock males and their broadsheets were a somewhat common culprit. It feels inaccurate to blame any single party (even Jann Wenner). In 2018, Hat and Beard Press released My Week Beats Your Year: Encounters With Lou Reed, a collection of 36 tussles that range in character from amicable slap-boxing to tearful negotiations. Sometimes Reed is responding in nasty bad faith when being asked anodyne questions about his Poe adaptation; other times, he’s fielding provocative tabloid nonsense about the “greasers” who “get off” to his music. It’s a bad soup. Howard Sounes, who published The Life of Lou Reed: Notes from the Velvet Underground in 2019, told me over the phone recently that “the problem isn’t with the journalists; the problem is with him.” Sounes never had the chance to interview Reed, who died in 2013, but among the people who knew him, Sounes noted, “the word that kept coming up was ‘prick.’”

To write about Lou Reed is to fight with Lou Reed. It is difficult to say, however, who started what, and there is more than a little evidence that the sourness of rock males and their broadsheets were a somewhat common culprit. It feels inaccurate to blame any single party (even Jann Wenner). In 2018, Hat and Beard Press released My Week Beats Your Year: Encounters With Lou Reed, a collection of 36 tussles that range in character from amicable slap-boxing to tearful negotiations. Sometimes Reed is responding in nasty bad faith when being asked anodyne questions about his Poe adaptation; other times, he’s fielding provocative tabloid nonsense about the “greasers” who “get off” to his music. It’s a bad soup. Howard Sounes, who published The Life of Lou Reed: Notes from the Velvet Underground in 2019, told me over the phone recently that “the problem isn’t with the journalists; the problem is with him.” Sounes never had the chance to interview Reed, who died in 2013, but among the people who knew him, Sounes noted, “the word that kept coming up was ‘prick.’” There are certain images that slither past good taste and politics and sink their teeth straight into the subconscious. For instance: a man dressed in a tuxedo and a Ronald Reagan mask, using a gasoline pump as a flamethrower. He is torching his getaway vehicle and taking his time; the scene isn’t shot in slow motion, but I always remember it that way. In about thirty seconds, a cop will tackle him, prompting a long foot chase, but for now he waves his weapon like a kid with a sparkler on New Year’s Eve. We can’t see his expression, but Reagan’s face is grinning, and I’d like to imagine that the face underneath is, too. Don’t all bad guys dream of being children again?

There are certain images that slither past good taste and politics and sink their teeth straight into the subconscious. For instance: a man dressed in a tuxedo and a Ronald Reagan mask, using a gasoline pump as a flamethrower. He is torching his getaway vehicle and taking his time; the scene isn’t shot in slow motion, but I always remember it that way. In about thirty seconds, a cop will tackle him, prompting a long foot chase, but for now he waves his weapon like a kid with a sparkler on New Year’s Eve. We can’t see his expression, but Reagan’s face is grinning, and I’d like to imagine that the face underneath is, too. Don’t all bad guys dream of being children again? Everyone knows politics makes people crazy. But what kind of crazy? Which page of the DSM is it on?

Everyone knows politics makes people crazy. But what kind of crazy? Which page of the DSM is it on? Last week, Austria-based Swarovski Optik

Last week, Austria-based Swarovski Optik  The binoculars, aimed mostly at bird watchers, gain their ability to identify birds from the

The binoculars, aimed mostly at bird watchers, gain their ability to identify birds from the  Sathnam Sanghera’s Empireworld tells the story of Bartram and Kew as part of a nuanced, complicated account of the British empire’s impact on the world as we know it, and it is a story that is strikingly, remarkably alive to the contradictions inherent in its telling. For example, the technologies that facilitated the transporting of the plants and seeds that changed the English landscape and accelerated modern plant science also drove the large-scale cultivation of indigo, sugar cane, and rubber, and thereby determined the destinies of countless thousands of enslaved and indentured labourers in British-owned plantations across the world. And these enterprises, leading as they did to the kind of large-scale ecological destruction whose effects are still felt today, also created a need for conservation movements and environmental activism. Neither global communication, nor global cuisines, would be the same without any of this.

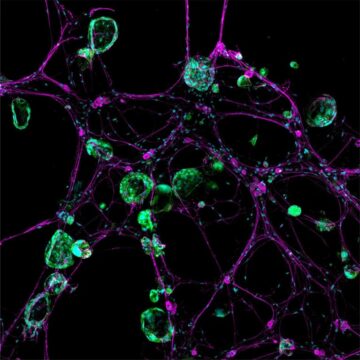

Sathnam Sanghera’s Empireworld tells the story of Bartram and Kew as part of a nuanced, complicated account of the British empire’s impact on the world as we know it, and it is a story that is strikingly, remarkably alive to the contradictions inherent in its telling. For example, the technologies that facilitated the transporting of the plants and seeds that changed the English landscape and accelerated modern plant science also drove the large-scale cultivation of indigo, sugar cane, and rubber, and thereby determined the destinies of countless thousands of enslaved and indentured labourers in British-owned plantations across the world. And these enterprises, leading as they did to the kind of large-scale ecological destruction whose effects are still felt today, also created a need for conservation movements and environmental activism. Neither global communication, nor global cuisines, would be the same without any of this. Lightning bolts of lime green flashed chaotically across the computer screen, a sight that stunned cancer neuroscientist Humsa Venkatesh. It was late 2017, and she was watching a storm of electrical activity in cells from a human brain tumour called a glioma. Venkatesh was expecting a little background chatter between the cancerous brain cells, just as there is between healthy ones. But the conversations were continuous, and rapid-fire. “I could see these tumour cells just lighting up,” says Venkatesh, who was then a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford University School of Medicine in Stanford, California. “They were so clearly electrically active.”

Lightning bolts of lime green flashed chaotically across the computer screen, a sight that stunned cancer neuroscientist Humsa Venkatesh. It was late 2017, and she was watching a storm of electrical activity in cells from a human brain tumour called a glioma. Venkatesh was expecting a little background chatter between the cancerous brain cells, just as there is between healthy ones. But the conversations were continuous, and rapid-fire. “I could see these tumour cells just lighting up,” says Venkatesh, who was then a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford University School of Medicine in Stanford, California. “They were so clearly electrically active.” As we embark on

As we embark on  Last week, a

Last week, a Neuralink was founded in 2016 by

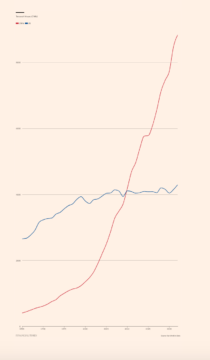

Neuralink was founded in 2016 by  As data from the IEA confirm, the scale of China’s green energy push in the last couple of years dwarfs the much ballyhooed green energy programs in the West – NextGenEU, IRA etc.

As data from the IEA confirm, the scale of China’s green energy push in the last couple of years dwarfs the much ballyhooed green energy programs in the West – NextGenEU, IRA etc. There was a brief period in the later part of the Covid-19 pandemic, between the moment when Glenn Youngkin swept into the Virginia governorship and the full political return of Donald Trump, when I became convinced that American liberalism was headed for a truly epochal defeat in 2024.

There was a brief period in the later part of the Covid-19 pandemic, between the moment when Glenn Youngkin swept into the Virginia governorship and the full political return of Donald Trump, when I became convinced that American liberalism was headed for a truly epochal defeat in 2024.