Shelly Fan in Singularity Hub:

The origin of consciousness has teased the minds of philosophers and scientists for centuries. In the last decade, neuroscientists have begun to piece together its neural underpinnings—that is, how the brain, through its intricate connections, transforms electrical signaling between neurons into consciousness. Yet the field is fragmented, an international team of neuroscientists recently wrote in a new paper in Neuron. Many theories of consciousness contradict each other, with different ideas about where and how consciousness emerges in the brain. Some theories are even duking it out in a mano-a-mano test by imaging the brains of volunteers as they perform different tasks in clinical test centers across the globe.

The origin of consciousness has teased the minds of philosophers and scientists for centuries. In the last decade, neuroscientists have begun to piece together its neural underpinnings—that is, how the brain, through its intricate connections, transforms electrical signaling between neurons into consciousness. Yet the field is fragmented, an international team of neuroscientists recently wrote in a new paper in Neuron. Many theories of consciousness contradict each other, with different ideas about where and how consciousness emerges in the brain. Some theories are even duking it out in a mano-a-mano test by imaging the brains of volunteers as they perform different tasks in clinical test centers across the globe.

But unlocking the neural basis of consciousness doesn’t have to be confrontational. Rather, theories can be integrated, wrote the authors, who were part of the Human Brain Project—a massive European endeavor to map and understand the brain—and specialize in decoding brain signals related to consciousness. Not all authors agree on the specific brain mechanisms that allow us to perceive the outer world and construct an inner world of “self.” But by collaborating, they merged their ideas, showing that different theories aren’t necessarily mutually incompatible—in fact, they could be consolidated into a general framework of consciousness and even inspire new ideas that help unravel one of the brain’s greatest mysteries.

More here.

This month marks 100 years since Mallory’s last dance with the sublime. Debate persists over whether a 1920s climber in hobnail boots, even a phenom like Mallory, could have made it past the Second Step, a technical and challenging 100-foot promontory, to reach the summit.

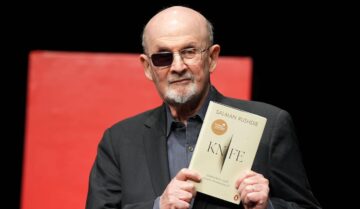

This month marks 100 years since Mallory’s last dance with the sublime. Debate persists over whether a 1920s climber in hobnail boots, even a phenom like Mallory, could have made it past the Second Step, a technical and challenging 100-foot promontory, to reach the summit. My copy of Salman Rushdie’s new book, Knife, arrived a few weeks ago, and before I had even opened the package, the news also arrived that Paul Auster had succumbed to cancer—and the confluence of Rushdie’s book and the information about Auster hit me harder than I would have predicted. Rushdie and Auster were friends. I knew this because in August 2022 there was a major assassination attempt on Rushdie—the assassination attempt is the topic of Knife—and a very few days later PEN America, the writers’ organisation, held a solidarity rally on the steps of the 42nd Street Library in New York. I attended, and I listened to Auster deliver a short speech. He celebrated Rushdie’s dedication to the storytelling imagination. He conjured the principle of freedom, and, in doing so, he expressed quietly an ardour of personal love, one friend for another in his moment of extreme trouble.

My copy of Salman Rushdie’s new book, Knife, arrived a few weeks ago, and before I had even opened the package, the news also arrived that Paul Auster had succumbed to cancer—and the confluence of Rushdie’s book and the information about Auster hit me harder than I would have predicted. Rushdie and Auster were friends. I knew this because in August 2022 there was a major assassination attempt on Rushdie—the assassination attempt is the topic of Knife—and a very few days later PEN America, the writers’ organisation, held a solidarity rally on the steps of the 42nd Street Library in New York. I attended, and I listened to Auster deliver a short speech. He celebrated Rushdie’s dedication to the storytelling imagination. He conjured the principle of freedom, and, in doing so, he expressed quietly an ardour of personal love, one friend for another in his moment of extreme trouble. History is repeating itself in Sudan. Tensions between rival security factions, which spilled out last April into open conflict, have rapidly created the world’s largest displacement crisis and food security crisis. Nearly half of the country’s 50 million people are in desperate need of food aid that is not reaching them, either because of access constraints or because it is simply not available.

History is repeating itself in Sudan. Tensions between rival security factions, which spilled out last April into open conflict, have rapidly created the world’s largest displacement crisis and food security crisis. Nearly half of the country’s 50 million people are in desperate need of food aid that is not reaching them, either because of access constraints or because it is simply not available. T

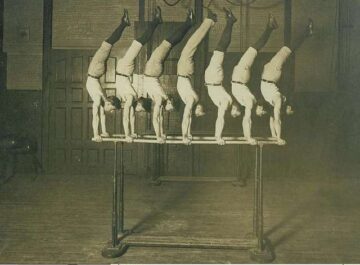

T On August 16, 1918, a bookkeeper in Denver named George Eyser wrote a will. He was not married and had no children. And so it was to his only sibling, his sister Ottilie, with whom he lived in a two-story brick house at 420 Downing Street, that he bequeathed his property and possessions: money, the proceeds from an insurance policy, a gold watch and chain, a scrapbook that chronicled the nearly three decades he spent as an amateur gymnast, and his crowning glory—the six Olympic medals he won on a single October day in 1904.

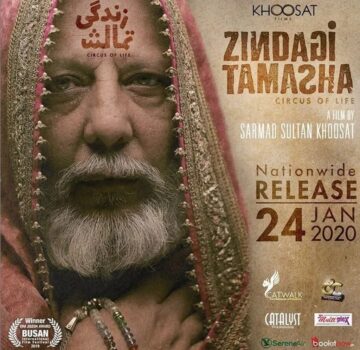

On August 16, 1918, a bookkeeper in Denver named George Eyser wrote a will. He was not married and had no children. And so it was to his only sibling, his sister Ottilie, with whom he lived in a two-story brick house at 420 Downing Street, that he bequeathed his property and possessions: money, the proceeds from an insurance policy, a gold watch and chain, a scrapbook that chronicled the nearly three decades he spent as an amateur gymnast, and his crowning glory—the six Olympic medals he won on a single October day in 1904. The difference between good art and bad art is that good art is subtle. Pakistan struggles to do subtle. There is certainly your everyday slapstick comedy, the tragic heroine, and the flippantly violent hero. But no, Pakistan is not at all good at subtle, which is why Sarmad Khoosat’s

The difference between good art and bad art is that good art is subtle. Pakistan struggles to do subtle. There is certainly your everyday slapstick comedy, the tragic heroine, and the flippantly violent hero. But no, Pakistan is not at all good at subtle, which is why Sarmad Khoosat’s  A

A  J

J For more than four years, reflexive partisan politics have derailed the search for the truth about a catastrophe that has touched us all. It has been estimated that

For more than four years, reflexive partisan politics have derailed the search for the truth about a catastrophe that has touched us all. It has been estimated that  After the murder of George Floyd in May 2020, former NBA player

After the murder of George Floyd in May 2020, former NBA player  When Schwartz comes up in conversation today, two things are typically remarked of him. First, he is a man whose reputation has eclipsed his work, his stature as a poet having surrendered to the clamor for myth. Second, this myth is one of vertiginous and scandalous decline. Delmore Schwartz: an American tragedy. Both commonplaces have the unfortunate merit of being true.

When Schwartz comes up in conversation today, two things are typically remarked of him. First, he is a man whose reputation has eclipsed his work, his stature as a poet having surrendered to the clamor for myth. Second, this myth is one of vertiginous and scandalous decline. Delmore Schwartz: an American tragedy. Both commonplaces have the unfortunate merit of being true. The coincidence of the centenary of Kafka’s death, on 3 June, and the publication of the first complete, uncensored

The coincidence of the centenary of Kafka’s death, on 3 June, and the publication of the first complete, uncensored