Owen Hatherley at the London Review of Books:

Adorno is easily parodied. Photos on social media show him frog-like, myopic and bald, denouncing the willing consumption of dross, the personal embodiment of a refusal to ‘let people enjoy things’. Another meme features Reverend Lovejoy from The Simpsons derisively brandishing a copy of Minima Moralia: ‘You ever sat down and read this thing?’ (In the original, it’s the Bible the reverend is holding up to ridicule.) Others use an image of Adorno in a one-piece swimsuit at the beach, looking as if he’s quietly enjoying himself – a more winsome George Costanza. These memes are surely made by people who had to study Adorno at university. They will probably have read the depressive aphorisms of Minima Moralia and some fragments from Dialectic of Enlightenment on the ‘culture industry’; a few unfortunates will have had to tackle the thickets of Aesthetic Theory or Negative Dialectics. Along with the parodies come received ideas: Adorno the grouch, Adorno the scourge of mass media, Adorno the mandarin Marxist; or, as Ben Watson puts it in his counterweight, Adorno for Revolutionaries (2011), Adorno as ‘a kind of German T.S. Eliot without the practical cats’.

Adorno is easily parodied. Photos on social media show him frog-like, myopic and bald, denouncing the willing consumption of dross, the personal embodiment of a refusal to ‘let people enjoy things’. Another meme features Reverend Lovejoy from The Simpsons derisively brandishing a copy of Minima Moralia: ‘You ever sat down and read this thing?’ (In the original, it’s the Bible the reverend is holding up to ridicule.) Others use an image of Adorno in a one-piece swimsuit at the beach, looking as if he’s quietly enjoying himself – a more winsome George Costanza. These memes are surely made by people who had to study Adorno at university. They will probably have read the depressive aphorisms of Minima Moralia and some fragments from Dialectic of Enlightenment on the ‘culture industry’; a few unfortunates will have had to tackle the thickets of Aesthetic Theory or Negative Dialectics. Along with the parodies come received ideas: Adorno the grouch, Adorno the scourge of mass media, Adorno the mandarin Marxist; or, as Ben Watson puts it in his counterweight, Adorno for Revolutionaries (2011), Adorno as ‘a kind of German T.S. Eliot without the practical cats’.

Adorno’s aesthetics are extreme. ‘He is an easy man to caricature,’ Watson writes, ‘because he believed in exaggeration as a means of telling the truth.’ But he was no misanthrope.

more here.

S

S Higher ed is at an impasse. So much about it sucks, and nothing about it is likely to change. Colleges and universities do not seem inclined to reform themselves, and if they were, they wouldn’t know how, and if they did, they couldn’t. Between bureaucratic inertia, faculty resistance, and the conflicting agendas of a heterogenous array of stakeholders, concerted change

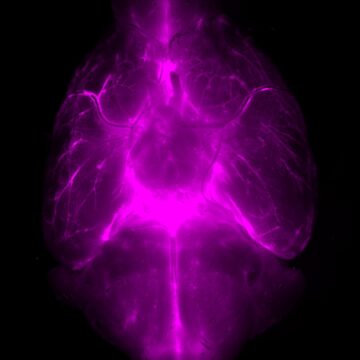

Higher ed is at an impasse. So much about it sucks, and nothing about it is likely to change. Colleges and universities do not seem inclined to reform themselves, and if they were, they wouldn’t know how, and if they did, they couldn’t. Between bureaucratic inertia, faculty resistance, and the conflicting agendas of a heterogenous array of stakeholders, concerted change  Genetic information usually travels down a one-way street:

Genetic information usually travels down a one-way street:  Every generation of adults thinks the next is growing up in a broken world. “It is the story of humanity,” says Jonathan Haidt, author of a new book on a youth mental illness epidemic called

Every generation of adults thinks the next is growing up in a broken world. “It is the story of humanity,” says Jonathan Haidt, author of a new book on a youth mental illness epidemic called  Strangeness – estrangement – is very characteristic of this world – and a world it is, since all these prose works convey a very similar atmosphere and are largely set in the same locale – the Norwegian west coast, with its fjords, its islands, its fishing villages, the omnipresent sometimes threatening, sometimes comforting sea. (It’s rather piquant for an Irish reader to see the word ‘skerries’ coming up often in the English translation – it means of course reefs or rocky islands from Old Norse sker and is a reminder of our own Norse inheritance.)

Strangeness – estrangement – is very characteristic of this world – and a world it is, since all these prose works convey a very similar atmosphere and are largely set in the same locale – the Norwegian west coast, with its fjords, its islands, its fishing villages, the omnipresent sometimes threatening, sometimes comforting sea. (It’s rather piquant for an Irish reader to see the word ‘skerries’ coming up often in the English translation – it means of course reefs or rocky islands from Old Norse sker and is a reminder of our own Norse inheritance.) Coppery like a penny, thick like bad molasses, even a little gamey like a possum.

Coppery like a penny, thick like bad molasses, even a little gamey like a possum. We all need sleep, but no one really knows why. For the past 10 years, a prevailing theory has been that a key function of sleep is to

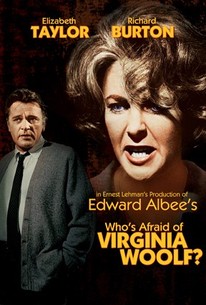

We all need sleep, but no one really knows why. For the past 10 years, a prevailing theory has been that a key function of sleep is to  Cocktails with George and Martha is a dishy, process-heavy appreciation of a cinematic masterpiece. Gefter shows how, after almost 60 years, the kitchen-sink savagery of the movie—and Edward Albee’s 1962 play, on which it is based—still shatters. The film portrays a long, cocktail-infused Saturday night at the home of middle-aged history professor George (played by Richard Burton in the movie) and his wife, Martha (Elizabeth Taylor). Martha has invited another couple over for drinks, with whom they begin to bicker, then flirt, then wage war. Their heaviest weapon is their imaginary child (they are, in fact, childless), whom they use as a punching bag and a life raft. Gefter locates Albee’s genius in the creation of the child and his poetic language, but also in the tender ending, which suggests that for George and Martha, at least, the sparring has been play-acting, albeit of the most serious kind.

Cocktails with George and Martha is a dishy, process-heavy appreciation of a cinematic masterpiece. Gefter shows how, after almost 60 years, the kitchen-sink savagery of the movie—and Edward Albee’s 1962 play, on which it is based—still shatters. The film portrays a long, cocktail-infused Saturday night at the home of middle-aged history professor George (played by Richard Burton in the movie) and his wife, Martha (Elizabeth Taylor). Martha has invited another couple over for drinks, with whom they begin to bicker, then flirt, then wage war. Their heaviest weapon is their imaginary child (they are, in fact, childless), whom they use as a punching bag and a life raft. Gefter locates Albee’s genius in the creation of the child and his poetic language, but also in the tender ending, which suggests that for George and Martha, at least, the sparring has been play-acting, albeit of the most serious kind. Imagine a machine that provides a simulation of any experience a person might want, but once the machine is activated, the person is unable to tell that the experience isn’t real. When Robert Nozick formulated this thought experiment in 1974, it was meant to be obvious that people in otherwise ordinary circumstances would be making a horrible mistake if they hooked themselves up to such a machine permanently. During the intervening decades, however, cultural commitment to that core value — the value of being in contact with reality as it is — has become more tenuous, and the empathic use of AI, in which people seek to be understood, cared for and even loved by a large language model (LLM), is on the rise.

Imagine a machine that provides a simulation of any experience a person might want, but once the machine is activated, the person is unable to tell that the experience isn’t real. When Robert Nozick formulated this thought experiment in 1974, it was meant to be obvious that people in otherwise ordinary circumstances would be making a horrible mistake if they hooked themselves up to such a machine permanently. During the intervening decades, however, cultural commitment to that core value — the value of being in contact with reality as it is — has become more tenuous, and the empathic use of AI, in which people seek to be understood, cared for and even loved by a large language model (LLM), is on the rise. Some 60,000 years ago, Neanderthals in western Eurasia acquired strange new neighbours: a wave of Homo sapiens migrants making their way out of Africa, en route to future global dominance. Now, a study

Some 60,000 years ago, Neanderthals in western Eurasia acquired strange new neighbours: a wave of Homo sapiens migrants making their way out of Africa, en route to future global dominance. Now, a study Imagine that in every business school students were told, in all seriousness, that they were in training for being a billionaire. Imagine it was heavily implied that the natural conclusion of their careers—what “making it” in business meant—was legit billionaire-status. Judged from the outside, such a situation would appear the enactment of a collective pathological delusion.

Imagine that in every business school students were told, in all seriousness, that they were in training for being a billionaire. Imagine it was heavily implied that the natural conclusion of their careers—what “making it” in business meant—was legit billionaire-status. Judged from the outside, such a situation would appear the enactment of a collective pathological delusion. IN AN

IN AN  Friends called her Anna Vassilievna, according to the Russian custom of having the patronym follow the given name. As evening fell, I often lay in my child’s pyjamas, on the living room sofa, close to my grandmother, my Babushka. The sofa stood in our living room in the Leipzig apartment, close to the large window. Some light came from the outside.

Friends called her Anna Vassilievna, according to the Russian custom of having the patronym follow the given name. As evening fell, I often lay in my child’s pyjamas, on the living room sofa, close to my grandmother, my Babushka. The sofa stood in our living room in the Leipzig apartment, close to the large window. Some light came from the outside.