The moon rose over the bay. I had a lot of feeling

I am taken with the hot animal

of my skin, grateful to swing my limbs

and have them move as I intend, though

my knee, though my shoulder, though something

is torn or tearing. Today, a dozen squid, dead

on the harbor beach: one mostly buried,

one with skin empty as a shell and hollow

feeling, and, though the tentacles look soft,

I do not touch them. I imagine they

were startled to find themselves in the sun.

I imagine the tide simply went out

without them. I imagine they cannot

feel the black flies charting the raised hills

of their eyes. I write my name in the sand:

Donika Kelly. I watch eighteen seagulls

skim the sandbar and lift low in the sky.

I pick up a pebble that looks like a green egg.

To the ditch lily I say I am in love.

To the Jeep parked haphazardly on the narrow

street I am in love. To the roses, white

petals rimmed brown, to the yellow lined

pavement, to the house trimmed in gold I am

in love. I shout with the rough calculus

of walking. Just let me find my way back,

let me move like a tide come in.

by Donika Kelly

from Poem-a-day, 11/20/2017

the Academy of American Poets.

The region, we’re told, extends from the deserts of Sonora to the straits of Tierra del Fuego, encompassing 7.7 million square miles that are home to 660 million people who share two Latinate languages: Spanish and Portuguese. What complicates the picture is that many in that vast expanse also speak Nahuatl, Quechua, and hundreds of other tongues. But it’s not just the language: the people of this region, we hear, are

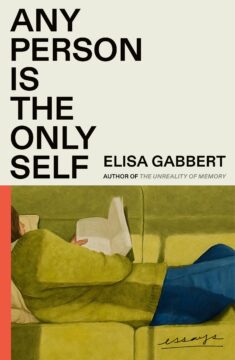

The region, we’re told, extends from the deserts of Sonora to the straits of Tierra del Fuego, encompassing 7.7 million square miles that are home to 660 million people who share two Latinate languages: Spanish and Portuguese. What complicates the picture is that many in that vast expanse also speak Nahuatl, Quechua, and hundreds of other tongues. But it’s not just the language: the people of this region, we hear, are  “Any Person Is the Only Self,” the poet and critic Elisa Gabbert’s third collection of nonfiction, opens with an essay that should be, but isn’t quite, a mission statement. She starts by describing the Denver Public Library’s shelf for recent returns, a miscellaneous display of disconnected works she habitually browsed in the years she lived in Colorado. In part, Gabbert (who is also the Book Review’s poetry columnist) was drawn to the shelf for its “negative hype,” its opposition to the churn of literary publicity. But mainly, she enjoyed playing the odds. “Randomness is interesting,” she writes; “randomness looks beautiful to me.” At the essay’s end, she declares, “I need randomness to be happy.”

“Any Person Is the Only Self,” the poet and critic Elisa Gabbert’s third collection of nonfiction, opens with an essay that should be, but isn’t quite, a mission statement. She starts by describing the Denver Public Library’s shelf for recent returns, a miscellaneous display of disconnected works she habitually browsed in the years she lived in Colorado. In part, Gabbert (who is also the Book Review’s poetry columnist) was drawn to the shelf for its “negative hype,” its opposition to the churn of literary publicity. But mainly, she enjoyed playing the odds. “Randomness is interesting,” she writes; “randomness looks beautiful to me.” At the essay’s end, she declares, “I need randomness to be happy.” We live in a weird time for autonomous vehicles. Ambitions come and go, but genuinely autonomous cars are further off than solid-state vehicle batteries. Part of the problem with developing autonomous cars is that teaching road cars to take risks is unacceptable.

We live in a weird time for autonomous vehicles. Ambitions come and go, but genuinely autonomous cars are further off than solid-state vehicle batteries. Part of the problem with developing autonomous cars is that teaching road cars to take risks is unacceptable.

The Bharatiya Janata party (BJP), led by India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, has

The Bharatiya Janata party (BJP), led by India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, has  The specter of failure, of course, looms large over creative people, whose identities are particularly bound up with their work; the stock character of the tortured artist dates back to Plato. Culturally, we tend to romanticize grandiose failure—artists who toiled in bitter agony or isolation or with complete lack of recognition their whole lives, only to become demigods after death (van Gogh, Emily Dickinson). In an essay in Boston Review, the critic Tom Bissell considers how fragile the phenomenon of writerly success is, exploring how names that are iconic and enduring today, like Herman Melville and Walt Whitman, could easily have been long lost, had it not been for an assortment of arbitrary occurrences: “Remaindered copies bought from book peddlers. A man, sitting at his desk, an oxidized copy of a forgotten novel beside him, cobbling together an essay with no idea of what it would accomplish.… Essays published at the right time, in the right journals or books, noticed by the right people.” The reasons many famous writers of yore continue to have star status has little to do with fate, Bissell writes, but rather with “the stagecraft of chance.” He quotes Melville—notoriously unsuccessful in his lifetime, writing to a friend in 1849 upon the flop of his novel Mardi. “[It] may possibly—by some miracle, that is—flower like aloe, a hundred years hence—or not flower at all, which is more likely by far, for some aloes never flower.”

The specter of failure, of course, looms large over creative people, whose identities are particularly bound up with their work; the stock character of the tortured artist dates back to Plato. Culturally, we tend to romanticize grandiose failure—artists who toiled in bitter agony or isolation or with complete lack of recognition their whole lives, only to become demigods after death (van Gogh, Emily Dickinson). In an essay in Boston Review, the critic Tom Bissell considers how fragile the phenomenon of writerly success is, exploring how names that are iconic and enduring today, like Herman Melville and Walt Whitman, could easily have been long lost, had it not been for an assortment of arbitrary occurrences: “Remaindered copies bought from book peddlers. A man, sitting at his desk, an oxidized copy of a forgotten novel beside him, cobbling together an essay with no idea of what it would accomplish.… Essays published at the right time, in the right journals or books, noticed by the right people.” The reasons many famous writers of yore continue to have star status has little to do with fate, Bissell writes, but rather with “the stagecraft of chance.” He quotes Melville—notoriously unsuccessful in his lifetime, writing to a friend in 1849 upon the flop of his novel Mardi. “[It] may possibly—by some miracle, that is—flower like aloe, a hundred years hence—or not flower at all, which is more likely by far, for some aloes never flower.” For Billie Holiday, solitude was no bargain. “In my solitude,” she tells us in one of her signature songs, she sits in her room, filled with despair, gloom everywhere, eminently sad, certain she’ll soon go mad. Were she alive today, Ms. Holiday would be astonished to learn that solitude is no longer the dark and dreary state described by the lyricists Eddie DeLange and Irving Mills, but one, au contraire, that needs to be cultivated on the way to a rounder, fuller, in many ways more healthy mental life.

For Billie Holiday, solitude was no bargain. “In my solitude,” she tells us in one of her signature songs, she sits in her room, filled with despair, gloom everywhere, eminently sad, certain she’ll soon go mad. Were she alive today, Ms. Holiday would be astonished to learn that solitude is no longer the dark and dreary state described by the lyricists Eddie DeLange and Irving Mills, but one, au contraire, that needs to be cultivated on the way to a rounder, fuller, in many ways more healthy mental life. The origin of consciousness has teased the minds of philosophers and scientists for centuries. In the last decade, neuroscientists have begun to piece together its neural underpinnings—that is, how the brain, through its intricate connections, transforms electrical signaling between neurons into consciousness. Yet the field is fragmented, an international team of neuroscientists recently

The origin of consciousness has teased the minds of philosophers and scientists for centuries. In the last decade, neuroscientists have begun to piece together its neural underpinnings—that is, how the brain, through its intricate connections, transforms electrical signaling between neurons into consciousness. Yet the field is fragmented, an international team of neuroscientists recently  This month marks 100 years since Mallory’s last dance with the sublime. Debate persists over whether a 1920s climber in hobnail boots, even a phenom like Mallory, could have made it past the Second Step, a technical and challenging 100-foot promontory, to reach the summit.

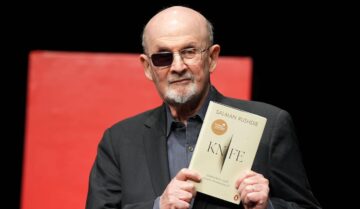

This month marks 100 years since Mallory’s last dance with the sublime. Debate persists over whether a 1920s climber in hobnail boots, even a phenom like Mallory, could have made it past the Second Step, a technical and challenging 100-foot promontory, to reach the summit. My copy of Salman Rushdie’s new book, Knife, arrived a few weeks ago, and before I had even opened the package, the news also arrived that Paul Auster had succumbed to cancer—and the confluence of Rushdie’s book and the information about Auster hit me harder than I would have predicted. Rushdie and Auster were friends. I knew this because in August 2022 there was a major assassination attempt on Rushdie—the assassination attempt is the topic of Knife—and a very few days later PEN America, the writers’ organisation, held a solidarity rally on the steps of the 42nd Street Library in New York. I attended, and I listened to Auster deliver a short speech. He celebrated Rushdie’s dedication to the storytelling imagination. He conjured the principle of freedom, and, in doing so, he expressed quietly an ardour of personal love, one friend for another in his moment of extreme trouble.

My copy of Salman Rushdie’s new book, Knife, arrived a few weeks ago, and before I had even opened the package, the news also arrived that Paul Auster had succumbed to cancer—and the confluence of Rushdie’s book and the information about Auster hit me harder than I would have predicted. Rushdie and Auster were friends. I knew this because in August 2022 there was a major assassination attempt on Rushdie—the assassination attempt is the topic of Knife—and a very few days later PEN America, the writers’ organisation, held a solidarity rally on the steps of the 42nd Street Library in New York. I attended, and I listened to Auster deliver a short speech. He celebrated Rushdie’s dedication to the storytelling imagination. He conjured the principle of freedom, and, in doing so, he expressed quietly an ardour of personal love, one friend for another in his moment of extreme trouble. History is repeating itself in Sudan. Tensions between rival security factions, which spilled out last April into open conflict, have rapidly created the world’s largest displacement crisis and food security crisis. Nearly half of the country’s 50 million people are in desperate need of food aid that is not reaching them, either because of access constraints or because it is simply not available.

History is repeating itself in Sudan. Tensions between rival security factions, which spilled out last April into open conflict, have rapidly created the world’s largest displacement crisis and food security crisis. Nearly half of the country’s 50 million people are in desperate need of food aid that is not reaching them, either because of access constraints or because it is simply not available. T

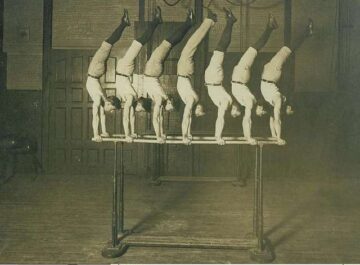

T On August 16, 1918, a bookkeeper in Denver named George Eyser wrote a will. He was not married and had no children. And so it was to his only sibling, his sister Ottilie, with whom he lived in a two-story brick house at 420 Downing Street, that he bequeathed his property and possessions: money, the proceeds from an insurance policy, a gold watch and chain, a scrapbook that chronicled the nearly three decades he spent as an amateur gymnast, and his crowning glory—the six Olympic medals he won on a single October day in 1904.

On August 16, 1918, a bookkeeper in Denver named George Eyser wrote a will. He was not married and had no children. And so it was to his only sibling, his sister Ottilie, with whom he lived in a two-story brick house at 420 Downing Street, that he bequeathed his property and possessions: money, the proceeds from an insurance policy, a gold watch and chain, a scrapbook that chronicled the nearly three decades he spent as an amateur gymnast, and his crowning glory—the six Olympic medals he won on a single October day in 1904.